Courage (also called bravery or valour) is the choice and willingness to confront agony, pain, danger, uncertainty, or intimidation. Physical courage is bravery in the face of physical pain, hardship, death or threat of death, while moral courage is the ability to act rightly in the face of popular opposition, shame, scandal, discouragement, or personal loss.

The classical virtue of fortitude (andreia, fortitudo) is also translated "courage", but includes the aspects of perseverance and patience.

In the Western tradition, notable thoughts on courage have come from philosophers, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, and Kierkegaard.

Much earlier, in the Hindu tradition, mythology has given many

examples of bravery, valour and courage. Ramayana and Mahabharatha have

in them many examples of both physical and moral courage.

In the Eastern tradition, some thoughts on courage were offered by the Tao Te Ching. More recently, courage has been explored by the discipline of psychology.

Characteristics of Courage

Daniel

Putman, a professor at the University of Wisconsin - Fox Valley, wrote

an article titled "The Emotions of Courage". Using a text from

Aristotle's Nicomanachean Ethics as the basis for his article, he discusses the relationship between fear and confidence in the emotion of courage.

First, in feelings of fear and confidence the mean is bravery (andreia).The excessively fearless person is nameless...while the one who is excessively confident is rash; the one who is excessively afraid and deficient in confidence is cowardly.

He states that "courage involves deliberate choice in the face of

painful or fearful circumstances for the sake of a worthy goal". With this realization, Putman concludes that "there is a close connection between fear and confidence".

Fear & Confidence in Relation to Courage

Fear and confidence in relation to courage can determine the success of a courageous act or goal.They can be seen as the independent variables in courage, and their relationship can affect how we respond to fear.

In addition, the confidence that is being discussed here is

self-confidence; Confidence in knowing one's skills and abilities and

being able determine when to fight a fear or when to flight it. Putman states that

The ideal in courage is not just a rigid control of fear, nor is it a denial of the emotion. The ideal is to judge a situation, accept the emotion as part of human nature and, we hope, use well-developed habits to confront the fear and allow reason to guide our behavior toward a worthwhile goal.

When trying to understand how fear and confidence play into

courage, we need to look back at Aristotle's quote. According to Putman,

Aristotle is referring to an appropriate level of fear and confidence

in courage.

"Fear, although it might vary from person to person, is not completely

relative and is only appropriate if it "matches the danger of the

situation"."The same goes for confidence in that there are two aspects to self-confidence in a dangerous situation.

- "a realistic confidence in the worth of a cause that motivates positive action."

- "knowing our own skills and abilities. A second meaning of appropriate confidence then is a form of self-knowledge."

Without an appropriate balance between fear and confidence when

facing a threat, one cannot have the courage to overcome it. Putman

states "if the two emotions are distinct, then excesses or deficiencies

in either fear or confidence can distort courage."

Possible Distortions of Courage

As noted above, an "excess or deficiency of either fear or confidence, can distort courage". According to Putman, there are four possibilities:

- "Higher level of fear than a situation calls for, low level of confidence"

- "Excessively low level of fear when real fear is appropriate, excessively high level of confidence."

- "Excessively high level of fear, yet the confidence is also excessively high."

- "Excessively low level of fear and low level of confidence."

Putman explains each of these possibilities accordingly: an

individual in the first possibility is perceived as a coward; in the

second possibility a rash person. .

For the remaining two possibilites, he uses analogies to explain them.

The third possibility can occur if someone experienced a traumatic

experience that brought about great anxiety for much of their life.Then the fear that they experience would often be inappropriate and excessive. Yet as a defensive mechanism, the person would show excessive levels of

confidence as a way to confront their irrational fear and ""prove"

something to oneself or other".

So this distortions could be seen as a coping method for their fear.

For the last possibility, it can be seen as hopelessness. Putman says

this is similar to "a person on a sinking ship". "This example is of a person who has low confidence and possibly low self-regard who suddenly loses all fear".

The distortion of low fear and low confidence can occur in a situation

where an individual accepts what is going to happen to them. In regards

to this example, they lose all fear because they know death is

unavoidable and the reason it is unavoidable is because they do not have

the ability to handle or overcome the situation.

Thus, Daniel Putman identifies fear and courage as being deeply intertwined and that they rely on distinct perceptions:

- "the danger of the situation"

- "the worthiness of the cause

- "and the perception of one's ability."

Theories

Ancient Greece

The early Greek philosopher Plato (c. 428–348 BCE) set the groundwork for how courage would be viewed to future philosophers. Plato's early writings found in Laches show a discussion on courage, but they fail to come to a satisfactory conclusion on what courage is.

During the debate between three leaders, including Socrates, many definitions of courage are mentioned.

- "…a man willing to remain at his post and to defend himself against the enemy without running away…"

- "…a sort of endurance of the soul…"

- "…knowledge of the grounds of fear and hope..."

While many definitions are given in Plato's Laches, all are refuted, giving the reader a sense of Plato's argument style. Laches

is an early writing of Plato's, which may be a reason he does not come

to a clear conclusion. In this early writing, Plato is still developing

his ideas and shows influence from his teachers like Socrates.

In one of his later writings, The Republic,

Plato gives more concrete ideas of what he believes courage to be.

Civic courage is described as a sort of perseverance – "preservation of

the belief that has been inculcated by the law through education about

what things and sorts of things are to be feared". Ideas of courage being perseverance also are seen in Laches. Plato further explains this perseverance as being able to persevere through all emotions, like suffering, pleasure, and fear.

As a desirable quality, courage is discussed broadly in Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, where its vice of shortage is cowardice and its vice of excess is recklessness.

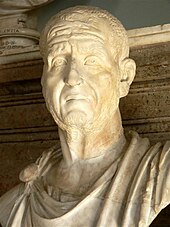

Ancient Rome

In the Roman Empire, courage formed part of the universal virtue of virtus. Roman philosopher and statesman Cicero (106–43 BCE) lists the cardinal virtues does not name them such:

Virtue may be defined as a habit of mind (animi) in harmony with reason and the order of nature. It has four parts: wisdom (prudentiam), justice, courage, temperance.

Medieval philosophy

In medieval virtue ethics, championed by Averroes and Thomas Aquinas and still important to Roman Catholicism, courage is referred to as "Fortitude".

According to Thomas Aquinas:

Among the cardinal virtues, prudence ranks first, justice second, fortitude third, temperance fourth, and after these the other virtues.

Part of his justification for this hierarchy is that:

Fortitude without justice is an occasion of injustice; since the stronger a man is the more ready is he to oppress the weaker.

On fortitude's general and special nature, Aquinas says:

The term "fortitude" can be taken in two ways. First, as simply denoting a certain firmness of mind, and in this sense it is a general virtue, or rather a condition of every virtue, since as the Philosopher states, it is requisite for every virtue to act firmly and immovably. Secondly, fortitude may be taken to denote firmness only in bearing and withstanding those things wherein it is most difficult to be firm, namely in certain grave dangers. Therefore Tully says, that "fortitude is deliberate facing of dangers and bearing of toils." On this sense fortitude is reckoned a special virtue, because it has a special matter.

Aquinas holds fortitude or courage as being primarily about endurance, not attack:

As stated above (Article 3), and according to the Philosopher, "fortitude is more concerned to allay fear, than to moderate daring." For it is more difficult to allay fear than to moderate daring, since the danger which is the object of daring and fear, tends by its very nature to check daring to increase fear. Now to attack belongs to fortitude in so far as the latter moderates daring, whereas to endure follows the repression of fear. Therefore the principal act of fortitude is endurance, that is to stand immovable in the midst of dangers rather than to attack them.

Western traditions

In both Catholicism and Anglicanism, courage is also one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. For Thomas Aquinas, Fortitude is the virtue to remove any obstacle that keeps the will from following reason. Thomas Aquinas argues that Courage is a virtue which, along with the Christian virtues in the Summa Theologica,

can only be exemplified with the presence of the Christian virtues:

faith, hope, and mercy. In order to understand true courage in

Christianity it takes someone who displays the virtues of faith, hope, and mercy. Courage is a natural virtue which Saint Augustine did not consider a virtue for Christians. Thomas Aquinas considers courage a virtue through the Christian virtue of mercy. Only through mercy and charity can we call the natural virtue of courage a Christian virtue. Unlike Aristotle, Aquinas’ courage is about endurance, not bravery in battle.

Eastern traditions

The Tao Te Ching contends that courage is derived from love ("慈 loving 故 causes 能 ability 勇 brave"), explaining, "One

of courage, with audacity, will die. One of courage, but gentle,

spares death. From these two kinds of courage arise harm and benefit."

In Hindu tradition, Courage (shauriya) / Bravery (dhairya), and

Patience (taamasa) appear as the first two of ten characteristics

(lakshana) of dharma in the Hindu Manusmṛti, besides forgiveness (kshama), tolerance (dama), honesty (asthaya), physical restraint (indriya nigraha), cleanliness (shouchya), perceptiveness (dhi), knowledge (vidhya), truthfulness (satya), and control of anger (akrodh).

Islamic beliefs also present courage and self-control as a key

factor in facing the Devil (both within and external); many believe this

because of the courage the Prophets of the past displayed (through

peace and patience) against people who despised them for their beliefs.

Recent past

Pre-19th century

Thomas Hobbes lists virtues into the categories of moral virtues and virtues of men in his work "Man and Citizen."

Hobbes outlines moral virtues as virtues in citizens, that is virtues

that without exception are beneficial to society as a whole.

These moral virtues are justice (i.e. not violating the law) and

charity. Courage as well as prudence and temperance are listed as the

virtues of men.

By this Hobbes means that these virtues are invested solely in the

private good as opposed to the public good of justice and charity.

Hobbes describes courage and prudence as a strength of mind as opposed

to a goodness of manners. These virtues are always meant to act in the

interests of individual while the positive and/or negative effects of

society are merely a byproduct. This stems forth from the idea put forth

in "Leviathan" that the state of nature

is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short." According to Hobbes

courage is a virtue of the individual in order to ensure a better chance

of survival while the moral virtues address Hobbes's social contract

which civilized men display (in varying degrees) in order to avoid the

state of nature.

Hobbes also uses the idea of fortitude as an idea of virtue. Fortitude

is "to dare" according to Hobbes, but also to "resist stoutly in present

dangers."

This a more in depth elaboration of Hobbes's concept of courage that is

addressed earlier in "Man and Citizen." This idea relates back to

Hobbes's idea that self-preservation is the most fundamental aspect of

behavior.

David Hume listed virtues into two categories in his work A Treatise of Human Nature

as artificial virtues and natural virtues. Hume noted in the Treatise

that courage is a natural virtue. In the Treatise's section Of Pride and Humility, Their Objects and Causes,

Hume clearly stated courage is a cause of pride: "Every valuable

quality of the mind, whether of the imagination, judgment, memory or

disposition; wit, good-sense, learning, courage, justice, integrity; all

these are the cause of pride; and their opposites of humility".

Hume also related courage and joy to have positive effects on the soul:

"(...) since the soul, when elevated with joy and courage, in a manner

seeks opposition, and throws itself with alacrity into any scene of

thought or action, where its courage meets with matter to nourish and

employ it".

Along with courage nourishing and employing, Hume also wrote that

courage defends humans in the Treatise: "We easily gain from the

liberality of others, but are always in danger of losing by their

avarice: Courage defends us, but cowardice lays us open to every

attack".

Hume wrote what excessive courage does to a hero's character in

the Treatise's section "Of the Other Virtues and Vices": "Accordingly we

may observe, that an excessive courage and magnanimity, especially when

it displays itself under the frowns of fortune, contributes in a great

measure, to the character of a hero, and will render a person the

admiration of posterity; at the same time, that it ruins his affairs,

and leads him into dangers and difficulties, with which otherwise he

would never have been acquainted".

Other understandings of courage that Hume offered can be derived

from Hume's views on morals, reason, sentiment, and virtue from his work

An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals.

19th century onward

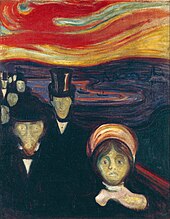

Søren Kierkegaard opposed courage to angst, while Paul Tillich opposed an existential courage to be with non-being, fundamentally equating it with religion:

Courage is the self-affirmation of being in spite of the fact of non-being. It is the act of the individual self in taking the anxiety of non-being upon itself by affirming itself ... in the anxiety of guilt and condemnation. ... every courage to be has openly or covertly a religious root. For religion is the state of being grasped by the power of being itself.

J.R.R. Tolkien identified in his 1936 lecture "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" a "Northern 'theory of courage'" – the heroic or "virtuous pagan" insistence to do the right thing even in the face of certain defeat without promise of reward or salvation:

It is the strength of the northern mythological imagination that it faced this problem, put the monsters in the centre, gave them victory but no honor, and found a potent and terrible solution in naked will and courage. 'As a working theory absolutely impregnable.' So potent is it, that while the older southern imagination has faded forever into literary ornament, the northern has power, as it were, to revive its spirit even in our own times. It can work, as it did even with the goðlauss Viking, without gods: martial heroism as its own end.

Virtuous pagan heroism or courage in this sense is "trusting in your own strength," as observed by Jacob Grimm in his Teutonic Mythology:

Men who, turning away in utter disgust and doubt from the heathen faith, placed their reliance on their own strength and virtue. Thus in the Sôlar lioð 17 we read of Vêbogi and Râdey â sik þau trûðu, "in themselves they trusted."

Ernest Hemingway famously defined courage as "grace under pressure."

Winston Churchill stated, "Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities because it is the quality that guarantees all others."

According to Maya Angelou,

"Courage is the most important of the virtues, because without courage

you can't practice any other virtue consistently. You can practice any

virtue erratically, but nothing consistently without courage."

In Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche describes master–slave morality,

in which a noble man regards himself as a "determiner of values;" one

who does not require approval, but passes judgment. Later, in the same

text, he lists man's four virtues as "courage, insight, sympathy, and

solitude," and goes on to emphasize the importance of courage: "The

great epochs of our life are the occasions when we gain the courage to

re-baptize our evil qualities as our best qualities."

According to the Swiss psychologist Andreas Dick, courage consists of the following components:

- put at risk, risk or repugnance, or sacrifice safety or convenience, which may result in death, bodily harm, social condemnation or emotional deprivation;

- a knowledge of wisdom and prudence about what is right and wrong in a given moment;

- Hope and confidence in a happy, meaningful outcome;

- a free will;

- a motive based on love.

Implicit Theories of Courage

Researchers

who want to study the concept and the emotion of courage have continued

to come across a certain problem. While there are "numerous definitions

of courage", they are unable to set "an operational definition of courage on which to base sound explicit theories". Rate et al. states that because of a lack of an operational definition, the advancement of research in courage is limited. So they conducted studies to try to find "a common structure of courage". Their goal from their research of implicit theories was to find "people's form and content on the idea of courage". Many researchers created studies on implicit theories by creating a questionnaire that would ask "What is courage?".

In addition, in order to "develop a measurement scale of courage, ten

experts in the field of psychology came together to define courage. They defined it as:

the ability to act for a meaningful (noble, good, or practical) cause, despite experiencing the fear associated with perceived threat exceeding the available resources

Also, because courage is a "multi-dimensional construct, it can be

"better understood as an exceptional response to specific external

conditions or circumstances than as an attribute, disposition, or

character trait". Meaning that rather than being a show of character or an attribute, courage is a response to fear.

From their research, they were able to find the "four necessary components of people's notion of courage"..They are:

- "intentionality/deliberation"

- "personal fear"

- "noble/good act"

- "and personal risk"

With these four components, they were able to define courage as:

a willful, intentional act, executed after mindful deliberation, involving objective substantial risk to the actor, primarily motivated to bring about a noble good or worthy end, despite, perhaps, the presence of the emotion of fear.

To further the discussion of the implicit theories of courage, the

researchers stated that future research could consider looking into the

concept of courage and fear and how individual's might feel fear,

overcome it and act, and act despite of it.

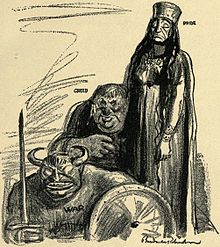

Society and symbolism

Its accompanying animal is the lion. Often, fortitude is depicted as having tamed the ferocious lion. Cf. e.g. the Tarot trump called Strength. It is sometimes seen in the Catholic Church as a depiction of Christ's triumph over sin. It also is a symbol in some cultures as a savior of the people who live in a community with sin and corruption.

Awards

Several awards claim to recognize courageous actions, including:

- The Edelstam Prize awarded for outstanding contributions and exceptional courage in standing up for one's beliefs in the defense of Human Rights.

- The Victoria Cross is the highest military award that may be received by members of the British Armed Forces and the Armed Forces of other Commonwealth countries for valour "in the face of the enemy", the civilian equivalent being the George Cross. A total of 1,356 VCs have been awarded to individuals, 13 since World War II.

- The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government. It is bestowed on members of the United States armed forces who distinguish themselves "conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States".

- Distinguished Service Cross (United States) is the second highest military decoration that can be awarded to a member of the United States Army, awarded for extreme gallantry and risk of life in actual combat with an armed enemy force.

- The Carnegie Hero Fund – was established to recognize persons who perform extraordinary acts of heroism in civilian life in the United States and Canada, and to provide financial assistance for those disabled and the dependents of those killed saving or attempting to save others.

- The Profile in Courage Award is a private award given to displays of courage similar to those John F. Kennedy described in his book Profiles in Courage. It is given to individuals (often elected officials) who, by acting in accord with their conscience, risked their careers or lives by pursuing a larger vision of the national, state or local interest in opposition to popular opinion or pressure from constituents or other local interests.

- The Civil Courage Prize is a human rights award which is awarded to "steadfast resistance to evil at great personal risk – rather than military valor." It is awarded by the Trustees of The Train Foundation annually and may be awarded posthumously.

- Courage to Care Award is a plaque with miniature bas-reliefs depicting the backdrop for the rescuers' exceptional deeds during the Nazis' persecution, deportation and murder of millions of Jews.

- The Ivan Allen Jr. Prize for Social Courage is a prize awarded by Georgia Institute of Technology to individuals who uphold the legacy of former Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen Jr., whose actions in Atlanta, Georgia and testimony before congress in support of the 1963 Civil Rights Bill legislation set a standard for courage during the turbulent civil rights era of the 1960s.

- The Param Vir Chakra is the highest military award in India given to those who show the highest degree of valour or self-sacrifice in the presence of the enemy. It can be, and often has been, awarded posthumously.

- The Military Order of Maria Theresa, the highest order of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, awarded for "successful military acts of essential impact to a campaign that were undertaken on [an officer's] own initiative, and might have been omitted by an honorable officer without reproach".