A Galapagos shark hooked by a fishing boat

In humans, pain

is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli.

Whether animals apart from humans also experience pain is often

contentious despite being scientifically verifiable. The standard

measure of pain in humans is how a person reports that pain, (for

example, on a pain scale). "Pain" is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage."

Only the person experiencing the pain can know the pain's quality and

intensity, and the degree of suffering. However, for non-human animals,

it is harder, if even possible, to know whether an emotional experience

has occurred. Therefore, this concept is often excluded in definitions of pain in animals,

such as that provided by Zimmerman: "an aversive sensory experience

caused by actual or potential injury that elicits protective motor and

vegetative reactions, results in learned avoidance and may modify

species-specific behavior, including social behavior."

Non-human animals cannot report their feelings to language-using humans

in the same manner as human communication, but observation of their

behavior provides a reasonable indication as to the extent of their

pain. Just as with doctors and medics who sometimes share no common

language with their patients, the indicators of pain can still be

understood.

According to the U.S. National Research Council Committee on

Recognition and Alleviation of Pain in Laboratory Animals, pain is

experienced by many animal species, including mammals and possibly all vertebrates.

The experience of pain

Although there are numerous definitions of pain, almost all involve two key components. First, nociception is required. This is the ability to detect noxious stimuli which evoke a reflex

response that rapidly moves the entire animal, or the affected part of

its body, away from the source of the stimulus. The concept of

nociception does not imply any adverse, subjective "feeling" – it is a

reflex action. An example in humans would be the rapid withdrawal of a

finger that has touched something hot – the withdrawal occurs before any

sensation of pain is actually experienced.

The second component is the experience of "pain" itself, or suffering

– the internal, emotional interpretation of the nociceptive experience.

Again in humans, this is when the withdrawn finger begins to hurt,

moments after the withdrawal. Pain is therefore a private, emotional

experience. Pain cannot be directly measured in other animals, including

other humans; responses to putatively painful stimuli can be measured,

but not the experience itself. To address this problem when assessing

the capacity of other species to experience pain, argument-by-analogy is

used. This is based on the principle that if an animal responds to a

stimulus in a similar way to ourselves, it is likely to have had an

analogous experience.

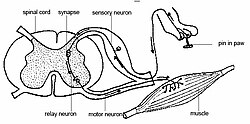

Reflex response to painful stimuli

Reflex

arc of a dog when its paw is stuck with a pin. The spinal cord responds

to signals from receptors in the paw, producing a reflex withdrawal of

the paw. This localized response does not involve brain processes that

might mediate a consciousness of pain, though these might also occur.

Nociception usually involves the transmission of a signal along nerve fibers

from the site of a noxious stimulus at the periphery to the spinal

cord. Although this signal is also transmitted on to the brain, a reflex response, such as flinching or withdrawal of a limb, is produced by return signals originating in the spinal cord. Thus, both physiological

and behavioral responses to nociception can be detected, and no

reference need be made to a conscious experience of pain. Based on such

criteria, nociception has been observed in all major animal taxa.

Awareness of pain

Nerve

impulses from nociceptors may reach the brain, where information about

the stimulus (e.g. quality, location, and intensity), and affect

(unpleasantness) are registered. Though the brain activity involved has

been studied, the brain processes underlying conscious awareness are not

well understood.

Adaptive value

The adaptive value

of nociception is obvious; an organism detecting a noxious stimulus

immediately withdraws the limb, appendage or entire body from the

noxious stimulus and thereby avoids further (potential) injury. However,

a characteristic of pain (in mammals at least) is that pain can result

in hyperalgesia (a heightened sensitivity to noxious stimuli) and allodynia

(a heightened sensitivity to non-noxious stimuli). When this heightened

sensitization occurs, the adaptive value is less clear. First, the pain

arising from the heightened sensitization can be disproportionate to

the actual tissue damage caused. Second, the heightened sensitization

may also become chronic, persisting well beyond the tissues healing.

This can mean that rather than the actual tissue damage causing pain, it

is the pain due to the heightened sensitization that becomes the

concern. This means the sensitization process is sometimes termed maladaptive.

It is often suggested hyperalgesia and allodynia assist organisms to

protect themselves during healing, but experimental evidence to support

this has been lacking.

In 2014, the adaptive value of sensitisation due to injury was tested using the predatory interactions between longfin inshore squid (Doryteuthis pealeii) and black sea bass (Centropristis striata)

which are natural predators of this squid. If injured squid are

targeted by a bass, they began their defensive behaviors sooner

(indicated by greater alert distances and longer flight initiation

distances) than uninjured squid. If anaesthetic (1% ethanol and MgCl2)

is administered prior to the injury, this prevents the sensitization

and blocks the behavioural effect. The authors claim this study is the

first experimental evidence to support the argument that nociceptive

sensitization is actually an adaptive response to injuries.

Argument-by-analogy

To assess the capacity of other species to consciously suffer pain we resort to argument-by-analogy.

That is, if an animal responds to a stimulus the way a human does, it

is likely to have had an analogous experience. If we stick a pin in a

chimpanzee's finger and she rapidly withdraws her hand, we use

argument-by-analogy and infer that like us, she felt pain. It might be

argued that consistency requires us infer, also, that a cockroach

experiences conscious pain when it writhes after being stuck with a pin.

The usual counter-argument is that although the physiology of

consciousness is not understood, it clearly involves complex brain

processes not present in relatively simple organisms. Other analogies have been pointed out. For example, when given a choice of foods, rats and chickens

with clinical symptoms of pain will consume more of an

analgesic-containing food than animals not in pain. Additionally, the

consumption of the analgesic carprofen in lame chickens was positively correlated to the severity of lameness, and consumption resulted in an improved gait. Such anthropomorphic

arguments face the criticism that physical reactions indicating pain

may be neither the cause nor result of conscious states, and the

approach is subject to criticism of anthropomorphic interpretation. For

example, a single-celled organism such as an amoeba may writhe after

being exposed to noxious stimuli despite the absence of nociception.

History

The idea that animals might not experience pain or suffering as humans do traces back at least to the 17th-century French philosopher, René Descartes, who argued that animals lack consciousness.

Researchers remained unsure into the 1980s as to whether animals

experience pain, and veterinarians trained in the U.S. before 1989 were

simply taught to ignore animal pain. In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, Bernard Rollin

was regularly asked to "prove" that animals are conscious, and to

provide "scientifically acceptable" grounds for claiming that they feel

pain. Some authors say that the view that animals feel pain differently is now a minority view.

Academic reviews of the topic are more equivocal, noting that, although

it is likely that some animals have at least simple conscious thoughts

and feelings, some authors continue to question how reliably animal mental states can be determined.

In different species

The

ability to experience pain in an animal, or another human for that

matter, cannot be determined directly but it may be inferred through

analogous physiological and behavioral reactions.

Although many animals share similar mechanisms of pain detection to

those of humans, have similar areas of the brain involved in processing

pain, and show similar pain behaviors, it is notoriously difficult to

assess how animals actually experience pain.

Nociception

Nociceptive

nerves, which preferentially detect (potential) injury-causing stimuli,

have been identified in a variety of animals, including invertebrates.

The medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, and sea slug are classic model systems for studying nociception. Many other vertebrate and invertebrate animals also show nociceptive reflex responses similar to our own.

Pain

Many animals

also exhibit more complex behavioral and physiological changes

indicative of the ability to experience pain: they eat less food, their

normal behavior is disrupted, their social behavior is suppressed,

they may adopt unusual behavior patterns, they may emit characteristic

distress calls, experience respiratory and cardiovascular changes, as

well as inflammation and release of stress hormones.

Some criteria that may indicate the potential of another species to feel pain include:

- Has a suitable nervous system and sensory receptors

- Physiological changes to noxious stimuli

- Displays protective motor reactions that might include reduced use of an affected area such as limping, rubbing, holding or autotomy

- Has opioid receptors and shows reduced responses to noxious stimuli when given analgesics and local anaesthetics

- Shows trade-offs between stimulus avoidance and other motivational requirements

- Shows avoidance learning

- High cognitive ability and sentience

Vertebrates

Fish

A typical human cutaneous nerve contains 83% C type trauma receptors (the type responsible for transmitting signals described by humans as excruciating pain); the same nerves in humans with congenital insensitivity to pain have only 24-28% C type receptors. The rainbow trout has about 5% C type fibers, while sharks and rays have 0%.

Nevertheless, fish have been shown to have sensory neurons that are

sensitive to damaging stimuli and are physiologically identical to human

nociceptors.

Behavioral and physiological responses to a painful event appear

comparable to those seen in amphibians, birds, and mammals, and

administration of an analgesic drug reduces these responses in fish.

Animal welfare advocates have raised concerns about the possible

suffering of fish caused by angling. Some countries, e.g. Germany, have

banned specific types of fishing, and the British RSPCA now formally prosecutes individuals who are cruel to fish.

Invertebrates

Though it has been argued that most invertebrates do not feel pain, there is some evidence that invertebrates, especially the decapod crustaceans (e.g. crabs and lobsters) and cephalopods (e.g. octopuses), exhibit behavioral and physiological reactions indicating they may have the capacity for this experience.

Nociceptors have been found in nematodes, annelids and molluscs. Most insects do not possess nociceptors, one known exception being the fruit fly. In vertebrates, endogenous opioids

are neurochemicals that moderate pain by interacting with opiate

receptors. Opioid peptides and opiate receptors occur naturally in

nematodes, molluscs, insects, and crustaceans.

The presence of opioids in crustaceans has been interpreted as an

indication that lobsters may be able to experience pain, although it has

been claimed "at present no certain conclusion can be drawn".

One suggested reason for rejecting a pain experience in

invertebrates is that invertebrate brains are too small. However, brain

size does not necessarily equate to complexity of function. Moreover, weight for body-weight, the cephalopod

brain is in the same size bracket as the vertebrate brain, smaller than

that of birds and mammals, but as big as or bigger than most fish

brains.

Since September 2010, all cephalopods being used for scientific

purposes in the EU are protected by EU Directive 2010/63/EU which states

"...there is scientific evidence of their [cephalopods] ability to

experience pain, suffering, distress and lasting harm. In the UK, animal protection legislation

means that cephalopods used for scientific purposes must be killed

humanely, according to prescribed methods (known as "Schedule 1 methods

of euthanasia") known to minimize suffering.

In medicine and research

Veterinary medicine

Veterinary medicine uses, for actual or potential animal pain, the same analgesics and anesthetics as used in humans.

Dolorimetry

Dolorimetry (dolor:

Latin: pain, grief) is the measurement of the pain response in animals,

including humans. It is practiced occasionally in medicine, as a

diagnostic tool, and is regularly used in research into the basic

science of pain, and in testing the efficacy of analgesics. Non-human

animal pain measurement techniques include the paw pressure test, tail flick test, hot plate test and grimace scales.

Laboratory animals

Animals are kept in laboratories for a wide range of reasons, some of

which may involve pain, suffering or distress, whilst others (e.g. many

of those involved in breeding) will not. The extent to which animal testing causes pain and suffering in laboratory animals is the subject of much debate. Marian Stamp Dawkins

defines "suffering" in laboratory animals as the experience of one of

"a wide range of extremely unpleasant subjective (mental) states." The U.S. National Research Council has published guidelines on the care and use of laboratory animals, as well as a report on recognizing and alleviating pain in vertebrates. The United States Department of Agriculture

defines a "painful procedure" in an animal study as one that would

"reasonably be expected to cause more than slight or momentary pain or

distress in a human being to which that procedure was applied." Some critics argue that, paradoxically, researchers raised in the era of increased awareness of animal welfare may be inclined to deny that animals are in pain simply because they do not want to see themselves as people who inflict it. PETA however argues that there is no doubt about animals in laboratories being inflicted with pain. In the UK, animal research likely to cause "pain, suffering, distress or lasting harm" is regulated by the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and research with the potential to cause pain is regulated by the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 in the US.

In the U.S., researchers are not required to provide laboratory

animals with pain relief if the administration of such drugs would

interfere with their experiment. Laboratory animal veterinarian Larry

Carbone writes, “Without question, present public policy allows humans

to cause laboratory animals unalleviated pain. The AWA, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,

and current Public Health Service policy all allow for the conduct of

what are often called “Category E” studies – experiments in which

animals are expected to undergo significant pain or distress that will

be left untreated because treatments for pain would be expected to

interfere with the experiment.”

Severity scales

Eleven

countries have national classification systems of pain and suffering

experienced by animals used in research: Australia, Canada, Finland,

Germany, The Republic of Ireland, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland,

Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. The US also has a mandated national

scientific animal-use classification system, but it is markedly

different from other countries in that it reports on whether

pain-relieving drugs were required and/or used.

The first severity scales were implemented in 1986 by Finland and the

UK. The number of severity categories ranges between 3 (Sweden and

Finland) and 9 (Australia). In the UK, research projects are classified

as "mild", "moderate", and "substantial" in terms of the suffering the

researchers conducting the study say they may cause; a fourth category

of "unclassified" means the animal was anesthetized and killed without

recovering consciousness. It should be remembered that in the UK system,

many research projects (e.g. transgenic breeding, feeding distasteful

food) will require a license under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986,

but may cause little or no pain or suffering. In December 2001, 39

percent (1, 296) of project licenses in force were classified as "mild",

55 percent (1, 811) as "moderate", two percent (63) as "substantial",

and 4 percent (139) as "unclassified".

In 2009, of the project licenses issued, 35 percent (187) were

classified as "mild", 61 percent (330) as "moderate", 2 percent (13) as

"severe" and 2 percent (11) as unclassified.

In the US, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

defines the parameters for animal testing regulations. It states, "The

ability to experience and respond to pain is widespread in the animal

kingdom...Pain is a stressor and, if not relieved, can lead to

unacceptable levels of stress and distress in animals. " The Guide

states that the ability to recognize the symptoms of pain in different

species is essential for the people caring for and using animals.

Accordingly, all issues of animal pain and distress, and their potential

treatment with analgesia and anesthesia, are required regulatory issues

for animal protocol approval.