From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Atlas Shrugged is a 1957 novel by

Ayn Rand. Rand's fourth and final novel, it was also her

longest, and the one she considered to be her

magnum opus in the realm of

fiction writing.

Atlas Shrugged includes elements of

science fiction,

mystery, and

romance, and it contains Rand's most extensive statement of

Objectivism in any of her works of fiction.

The book depicts a

dystopian United States

in which private businesses suffer under increasingly burdensome laws

and regulations. Railroad executive Dagny Taggart and her lover, steel

magnate Hank Rearden, struggle against "looters" who want to exploit

their productivity. Dagny and Hank discover that a mysterious figure

called John Galt is persuading other business leaders to abandon their

companies and disappear as a "strike" of productive individuals against

the looters. The novel ends with the strikers planning to build a new

capitalist society based on Galt's philosophy of

reason and

individualism.

The theme of

Atlas Shrugged, as Rand described it, is "the

role of man's mind in existence". The book explores a number of

philosophical themes from which Rand would subsequently develop

Objectivism.

In doing so, it expresses the advocacy of reason, individualism, and

capitalism, and depicts what Rand saw to be the failures of governmental

coercion.

Atlas Shrugged received largely negative reviews after its

1957 publication, but achieved enduring popularity and consistent sales

in the following decades.

History

Context and writing

Rand's

stated goal for writing the novel was "to show how desperately the

world needs prime movers and how viciously it treats them" and to

portray "what happens to the world without them".

The core idea for the book came to her after a 1943 telephone

conversation with a friend, who asserted that Rand owed it to her

readers to write fiction about her philosophy. Rand replied, "What if I

went on strike? What if all the creative minds of the world went on

strike?" Rand then began

Atlas Shrugged to depict the

morality of rational self-interest, by exploring the consequences of a

strike

by intellectuals refusing to supply their inventions, art, business

leadership, scientific research, or new ideas to the rest of the world.

To produce

Atlas Shrugged, Rand conducted research on the

American railroad industry. Her previous work on a proposed (but never

realized) screenplay based on the development of the

atomic bomb, including her interviews of

J. Robert Oppenheimer, was used in the portrait of the character

Robert Stadler

and the novel's depiction of the development of "Project X". To do

further background research, Rand toured and inspected a number of

industrial facilities, such as the

Kaiser Steel plant, rode the locomotives of the

New York Central Railroad, and even learned to operate the locomotive of the

Twentieth Century Limited (and proudly reported that when operating it, "nobody touched a lever except me").

Rand's self-identified literary influences include

Victor Hugo,

Fyodor Dostoyevsky,

Edmond Rostand, and

O. Henry. In addition,

Justin Raimondo has observed similarities between

Atlas Shrugged and the 1922 novel

The Driver, written by

Garet Garrett,

which concerns an idealized industrialist named Henry Galt, who is a

transcontinental railway owner trying to improve the world and fighting

against government and socialism. In contrast,

Chris Matthew Sciabarra found Raimondo's "claims that Rand plagiarized ...

The Driver" to be "unsupported", and

Stephan Kinsella doubts that Rand was in any way influenced by Garrett.

Writer Bruce Ramsey said both novels "have to do with running railroads

during an economic depression, and both suggest pro-capitalist ways in

which the country might get out of the depression. But in plot,

character, tone, and theme they are very different."

Atlas Shrugged was Rand's last completed work of fiction.

It marked a turning point in her life—the end of her career as a

novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.

Publishing history

Random House CEO Bennett Cerf oversaw the novel's publication in 1957.

Due to the success of Rand's 1943 novel

The Fountainhead, she had no trouble attracting a publisher for

Atlas Shrugged.

This was a contrast to her previous novels, which she had struggled to

place. Even before she began writing it, she had been approached by

publishers interested in her next novel. However, her contract for

The Fountainhead gave the first option to its publisher,

Bobbs-Merrill Company.

After reviewing a partial manuscript, they asked her to discuss a

number of cuts and other changes. She refused, and Bobbs-Merrill

rejected the book.

Hiram Hayden, an editor she liked who had left Bobbs-Merrill, asked her to consider his new employer,

Random House. In an early discussion about the difficulties of publishing a controversial novel, Random House president

Bennett Cerf

proposed that Rand should submit the manuscript to multiple publishers

simultaneously and ask how they would respond to its ideas, so she could

evaluate who might best promote her work. Rand was impressed by the

bold suggestion and by her overall conversations with them. After

speaking with a few other publishers, of about a dozen who were

interested, Rand decided multiple submissions were not needed; she

offered the manuscript to Random House. Upon reading the portion Rand

submitted, Cerf declared it a "great book" and offered Rand a contract.

It was the first time Rand had worked with a publisher whose executives

seemed truly enthusiastic about one of her books.

Random House published the novel on October 10, 1957. The initial

print run was 100,000 copies. The first paperback edition was published

by

New American Library in July 1959, with an initial run of 150,000. A 35th-anniversary edition was published by

E. P. Dutton in 1992, with an introduction by Rand's legal heir,

Leonard Peikoff. The novel has been translated into more than 25 languages.

Title and chapters

The working title throughout its writing was

The Strike, but thinking this title would have revealed the mystery element of the novel prematurely, Rand was pleased when her husband suggested

Atlas Shrugged, previously the title of a single chapter, for the book. The title is a reference to

Atlas, a

Titan

of Greek mythology, described in the novel as "the giant who holds the

world on his shoulders". The significance of this reference appears in a

conversation between the characters

Francisco d'Anconia and

Hank Rearden,

in which d'Anconia asks Rearden what advice he would give Atlas upon

seeing "the greater [the titan's] effort, the heavier the world bore

down on his shoulders". With Rearden unable to answer, d'Anconia gives

his own response: "To shrug".

The novel is divided into three parts consisting of ten chapters each.

Robert James Bidinotto

said, "the titles of the parts and chapters suggest multiple layers of

meaning. The three parts, for example, are named in honor of Aristotle's

laws of logic ...

Part One is titled 'Non-Contradiction' ... Part Two, titled

'Either-Or' ... [and] Part Three is titled 'A Is A', a reference to 'the

Law of Identity'."

Synopsis

Setting

Atlas Shrugged is set in a

dystopian United States at an unspecified time, in which the country has a "National Legislature" instead of

Congress and a "Head of State" instead of a

President.

The government has increasingly extended its control over businesses

with increasingly stringent regulations. The United States also appears

to be approaching an

economic collapse, with widespread

shortages, constant

business failures,

and severely decreased productivity. Writer Edward Younkins said, "The

story may be simultaneously described as anachronistic and timeless. The

pattern of industrial organization appears to be that of the late

1800s—the mood seems to be close to that of the depression-era 1930s.

Both the social customs and the level of technology remind one of the

1950s". Many early 20th-century technologies are available, and the steel and railroad industries are especially significant;

jet planes are described as a relatively new technology, and

television is significantly less influential than

radio. Although other countries are mentioned in passing, the

Soviet Union,

World War II, or the

Cold War are not. The countries of the world are implied to be organized along vaguely

Marxist

lines, with references to "People's States" in Europe and South

America. Characters also refer to nationalization of businesses in these

"People's States", as well as in America. The economy of the book's

present is contrasted with the capitalism of 19th century America,

recalled as a lost

Golden Age.

Plot

Dagny Taggart, the Operating Vice President of railroad company Taggart Transcontinental, attempts to keep the company alive against

collectivism and

statism amid a sustained

economic depression.

While economic conditions worsen and government agencies enforce their

control on successful businesses, people are often heard repeating the

cryptic phrase "Who is

John Galt?",

in response to questions to which the individual has no answer. It

sarcastically means: "Don't ask important questions, because we don't

have answers"; or more broadly, "What's the point?" or "Why bother?".

Her brother

James,

the railroad's president, seems to make irrational decisions, such as

preferring to buy steel from Orren Boyle's unreliable Associated Steel,

rather than

Hank Rearden's

Rearden Steel. Dagny attempts to ignore her brother and pursue her own

policies. She is nevertheless disappointed to discover that the

Argentine billionaire

Francisco d'Anconia, her childhood friend and first love, appears to be destroying his family's international

copper company without cause by constructing the San Sebastián

copper mines, despite the fact that

Mexico is planning to

nationalize

the mines. She soon realizes that d'Anconia is actually taking

advantage of the investors by building worthless mines. Despite the

risk, Jim and his allies at Associated Steel invest a large amount of

capital into building a railway in the region while ignoring the more

crucial Rio Norte Line in

Colorado,

where the rival Phoenix-Durango Railroad competes by transporting

supplies for Ellis Wyatt, who has revitalized the region after

discovering large

oil reserves.

Dagny minimizes losses on the San Sebastian Line by placing obsolete

trains on the line, which Jim is forced to take credit for after the

line is nationalized as Dagny predicted. Meanwhile, in response to the

success of Phoenix-Durango, the National Alliance of Railroads, a group

containing the railroad companies of the United States, passes a rule

prohibiting competition in economically-prosperous areas while forcing

other railroads to extend rail service to "blighted" areas of the

country, with seniority going to more established railroads. The ruling

effectively ruins Phoenix-Durango, upsetting Dagny. Wyatt subsequently

arrives in Dagny's office and presents her with a nine-month ultimatum:

if she does not supply adequate rail service to his wells by the time

the ruling takes effect, he will not use her service, effectively

ensuring financial failure for Taggart Transcontinental.

In

Philadelphia,

Hank Rearden, a self-made steel magnate, has developed an alloy called

Rearden Metal, which is simultaneously lighter and stronger than

conventional steel. Rearden keeps its composition secret, sparking

jealousy among competitors. Dagny opts to use Rearden Metal in the Rio

Norte Line, becoming the first major customer to purchase the product.

As a result, pressure is put on Dagny to use conventional steel, but she

refuses. Hank's career is hindered by his feelings of obligation to his

wife, mother, and younger brother. After Hank refuses to sell the metal

to the State Science Institute, a government research foundation run by

Dr. Robert Stadler, the Institute publishes a report condemning the

metal without actually identifying problems with it. As a result, many

significant organizations

boycott

the line. Although Stadler agrees with Dagny's complaints over the

unscientific tone of the report, he refuses to override it. Dagny also

becomes acquainted with

Wesley Mouch, a

Washington lobbyist

initially working for Rearden, whom he betrays, and later notices the

nation's most capable business leaders abruptly disappearing, leaving

their industries to failure. The most recent of these is Ellis Wyatt,

who leaves his most successful oil well spewing

petroleum and

fire into the air (later named "Wyatt's Torch"). Each of these men remains absent despite a thorough search by politicians.

Having demonstrated the reliability of Rearden Metal in a

railroad line named after John Galt, Hank and Dagny become lovers, and

later discover, among the ruins of an abandoned factory, an incomplete

motor that transforms atmospheric

static electricity into

kinetic energy,

of which they seek the inventor. Eventually, this search reveals the

reason for business leaders' disappearances: the inventor of the motor

is John Galt, who is leading an organized strike of business leaders

against a society that demands that they be sacrificed. Dagny's private

plane crashes in their hiding place, an isolated valley known as Galt's

Gulch. While she recovers from her injuries, she hears the strikers'

explanations for the strike, and learns that Francisco is one of the

strikers. Galt asks her to join the strike.

Reluctant to abandon her railroad, Dagny leaves Galt's Gulch. But Galt follows her to

New York City,

where he hacks into a national radio broadcast to deliver a long speech

(70 pages in the first edition) to explain the novel's theme and Rand's

Objectivism.

As the government collapses, the authorities capture Galt, but he is

rescued by his partisans, while New York City loses its electricity. The

novel closes as Galt announces that they will later reorganize the

world.

Themes

Philosophy

The story of

Atlas Shrugged dramatically expresses Rand's

ethical egoism, her advocacy of "

rational selfishness",

whereby all of the principal virtues and vices are applications of the

role of reason as man's basic tool of survival (or a failure to apply

it): rationality, honesty, justice, independence, integrity,

productiveness, and pride. Rand's characters often personify her view of

the archetypes of various schools of philosophy for living and working

in the world. Robert James Bidinotto wrote, "Rand rejected the literary

convention that depth and plausibility demand characters who are

naturalistic replicas of the kinds of people we meet in everyday life,

uttering everyday dialogue and pursuing everyday values. But she also

rejected the notion that characters should be symbolic rather than

realistic."

and Rand herself stated, "My characters are never symbols, they are

merely men in sharper focus than the audience can see with unaided

sight. ... My characters are persons in whom certain human attributes

are focused more sharply and consistently than in average human beings".

In addition to the plot's more obvious statements about the

significance of industrialists to society, and the sharp contrast to

Marxism and the

labor theory of value,

this explicit conflict is used by Rand to draw wider philosophical

conclusions, both implicit in the plot and via the characters' own

statements.

Atlas Shrugged caricatures

fascism,

socialism,

communism,

and any state intervention in society, as allowing unproductive people

to "leech" the hard-earned wealth of the productive, and Rand contends

that the outcome of any individual's life is purely a function of its

ability, and that any individual could overcome adverse circumstances,

given ability and intelligence.

Sanction of the victim

The

concept "sanction of the victim" is defined by Leonard Peikoff as "the

willingness of the good to suffer at the hands of the

evil, to accept the role of sacrificial victim for the '

sin' of creating values". Accordingly, throughout

Atlas Shrugged,

numerous characters are frustrated by this sanction, as when Hank

Rearden appears duty-bound to support his family, despite their

hostility toward him; later, the principle is stated by

Dan Conway:

"I suppose somebody's got to be sacrificed. If it turned out to be me, I

have no right to complain". John Galt further explains the principle:

"Evil is impotent and has no power but that which we let it extort from

us", and, "I saw that evil was impotent ... and the only weapon of its

triumph was the willingness of the good to serve it".

Government and business

Rand's

view of the ideal government is expressed by John Galt: "The political

system we will build is contained in a single moral premise: no man may

obtain any values from others by resorting to physical force", whereas

"no rights can exist without the right to translate one's rights into

reality—to think, to work and to keep the results—which means: the right

of property". Galt himself lives a life of

laissez-faire capitalism.

At the end of the book, when the protagonists get ready to return

and claim the ravaged world, Judge Narragansett drafts a new Amendment

to the

United States Constitution: "

Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of production and trade". He is also "marking and crossing out the contradictions" in the Constitution's existing text.

In the world of

Atlas Shrugged, society stagnates when

independent productive agencies are socially demonized for their

accomplishments. This is in agreement with an excerpt from a 1964

interview with

Playboy

magazine, in which Rand states: "What we have today is not a capitalist

society, but a mixed economy—that is, a mixture of freedom and

controls, which, by the presently dominant trend, is moving toward

dictatorship. The action in

Atlas Shrugged takes place at a time

when society has reached the stage of dictatorship. When and if this

happens, that will be the time to go on strike, but not until then".

Rand also depicts

public choice theory, such that the language of

altruism is used to pass legislation nominally in the public interest (

e.g., the "Anti-Dog-Eat-Dog Rule", and "The Equalization of Opportunity Bill"), but more to the short-term benefit of

special interests and government agencies.

Property rights and individualism

Rand's

heroes continually oppose "parasites", "looters", and "moochers" who

demand the benefits of the heroes' labor. Edward Younkins describes Atlas Shrugged

as "an apocalyptic vision of the last stages of conflict between two

classes of humanity—the looters and the non-looters. The looters are

proponents of high taxation, big labor, government ownership, government

spending, government planning, regulation, and redistribution".

"Looters" are Rand's depiction of bureaucrats and government

officials, who confiscate others' earnings by the implicit threat of

force ("at the point of a gun"). Some officials execute government

policy, such as those who confiscate one state's

seed grain

to feed the starving citizens of another; others exploit those

policies, such as the railroad regulator who illegally sells the

railroad's supplies for his own profit. Both use force to take property

from the people who produced or earned it.

"Moochers" are Rand's depiction of those unable to produce value

themselves, who demand others' earnings on behalf of the needy, but

resent the talented upon whom they depend, and appeal to "moral right"

while enabling the "lawful" seizure by governments.

The character Francisco d'Anconia indicates the role of "looters"

and "moochers" in relation to money: "So you think that money is the

root of all evil? ... Have you ever asked what is the root of money?

Money is a tool of exchange, which can't exist unless there are goods

produced and men able to produce them. ... Money is not the tool of the

moochers, who claim your product by tears, or the looters who take it

from you by force. Money is made possible only by the men who produce."

Genre

The novel includes elements of

mystery,

romance, and

science fiction. Rand referred to

Atlas Shrugged as a mystery novel, "not about the murder of man's body, but about the murder—and rebirth—of man's spirit". Nonetheless, when asked by film producer

Albert S. Ruddy if a screenplay could focus on the love story, Rand agreed and reportedly said, "That's all it ever was".

Technological progress and intellectual breakthroughs in scientific theory appear in

Atlas Shrugged, leading some observers to classify it in the genre of science fiction. Writer Jeff Riggenbach notes: "Galt's motor is one of the three inventions that propel the action of

Atlas Shrugged", the other two being Rearden Metal and the government's sonic weapon, Project X. Other fictional technologies are "refractor rays" (to disguise Galt's Gulch), a sophisticated electrical

torture device (the Ferris Persuader),

voice-activated door locks (at the Gulch's power station),

palm-activated

door locks (in Galt's New York laboratory), Galt's means of quietly

turning the entire contents of his laboratory into a fine powder when a

lock is breached, and a means of taking over all radio stations

worldwide. Riggenbach adds, "Rand's overall message with regard to

science seems clear: the role of science in human life and human society

is to provide the knowledge on the basis of which technological

advancement and the related improvements in the quality of human life

can be realized. But science can fulfill this role only in a society in

which human beings are left free to conduct their business as they see

fit." Science fiction historian

John J. Pierce describes it as a "romantic suspense novel" that is "at least a borderline case" of science fiction.

The chapter entitled "The Utopia of Greed", depicting Dagny

Taggart's experiences in Galt's Gulch, follows precisely the format of

Utopian Literature, as ultimately derived from

Sir Thomas More's 1516 book

Utopia.

As in other works falling within this genre, a visitor (in this case,

Dagny) arrives at an Utopian Society and is shown around by denizens,

who explain in detail how their social institutions work and what is the

world view behind these institutions.

Reception

Sales

Atlas Shrugged debuted on

The New York Times

Bestseller List at No. 13 three days after its publication. It peaked

at No. 3 on December 8, 1957, and was on the list for 22 consecutive

weeks. By 1984, its sales had exceeded five million copies.

Sales of

Atlas Shrugged increased following the

2007 financial crisis.

The Economist

reported that the 52-year-old novel ranked No. 33 among Amazon.com's

top-selling books on January 13, 2009, and that its 30-day sales average

showed the novel selling three times faster than during the same period

of the previous year. With an attached sales chart,

The Economist reported that sales "spikes" of the book seemed to coincide with the release of economic data. Subsequently, on April 2, 2009,

Atlas Shrugged ranked No. 1 in the "Fiction and Literature" category at Amazon and No. 15 in overall sales. Total sales of the novel in 2009 exceeded 500,000 copies. The book sold 445,000 copies in 2011, the second-strongest sales year in the novel's history.

Contemporary reviews

Atlas Shrugged was generally disliked by critics. Rand scholar

Mimi Reisel Gladstein

later wrote that "reviewers seemed to vie with each other in a contest

to devise the cleverest put-downs"; one called it "execrable claptrap",

while another said it showed "remorseless hectoring and prolixity". In the

Saturday Review, Helen Beal Woodward said that the novel was written with "dazzling virtuosity" but was "shot through with hatred". This was echoed by

Granville Hicks in

The New York Times Book Review, who said the book was "written out of hate". The reviewer for

Time magazine asked: "Is it a novel? Is it a nightmare? Is it Superman – in the comic strip or the Nietzschean version?" In the

National Review,

Whittaker Chambers called

Atlas Shrugged "sophomoric" and "remarkably silly", and said it "can be called a novel only by devaluing the term". Chambers argued against the novel's implicit endorsement of

atheism

and said the implicit message of the novel is akin to "Hitler's

National Socialism and Stalin's brand of Communism": "To a gas

chamber—go!"

The negative reviews produced responses from some of Rand's admirers.

Alan Greenspan wrote a letter to

The New York Times Book Review,

in which he responded to Hicks' claim that "the book was written out of

hate" by calling it "a celebration of life and happiness. Justice is

unrelenting. Creative individuals and undeviating purpose and

rationality achieve joy and fulfillment. Parasites who persistently

avoid either purpose or reason perish as they should." In a letter to the

National Review (which they did not publish), Leonard Peikoff wrote, "... Mr. Chambers is an ex-Communist. He has attacked

Atlas Shrugged in the best tradition of the Communists—by lies, smears, and cowardly misrepresentations."

There were some positive reviews. Richard McLaughlin, reviewing the novel for

The American Mercury,

described it as a "long overdue" polemic against the welfare state with

an "exciting, suspenseful plot", although unnecessarily long. He drew a

comparison with the antislavery novel

Uncle Tom's Cabin, saying that a "skillful polemicist" did not need a refined literary style to have a political impact. Journalist and book reviewer

John Chamberlain, writing in the

New York Herald Tribune, found

Atlas Shrugged satisfying on many levels: as science fiction, as a "philosophical detective story", and as a "profound political parable". In a tribute written on the 20th anniversary of the novel's publication,

John Hospers, a leading philosopher of aesthetics, praised it as "a supreme achievement, guaranteed of immortality".

Influence and legacy

Atlas Shrugged has attracted an energetic and committed fan

base. Each year, the Ayn Rand Institute donates 400,000 copies of works

by Rand, including

Atlas Shrugged, to high school students. According to a 1991 survey done for the

Library of Congress and the

Book of the Month Club,

Atlas Shrugged

was mentioned among the books that made the most difference in the

lives of 17 out of 5,000 Book-of-the-Month club members surveyed, which

placed the novel between the

Bible and

M. Scott Peck's

The Road Less Traveled.

Modern Library's 1998 nonscientific

online poll of the 100 best novels of the 20th century found

Atlas rated No. 1, although it was not included on the list chosen by the Modern Library board of authors and scholars.

Rand's impact on contemporary

libertarian thought has been considerable. The title of one libertarian magazine,

Reason: Free Minds, Free Markets, is taken directly from John Galt, the hero of

Atlas Shrugged,

who argues that "a free mind and a free market are corollaries". In

1983, the Libertarian Futurist Society gave the novel one of its first

"Hall of Fame" awards. In 1997, the libertarian

Cato Institute held a joint conference with

The Atlas Society, an Objectivist organization, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the publication of

Atlas Shrugged. At this event, Howard Dickman of

Reader's Digest

stated that the novel had "turned millions of readers on to the ideas

of liberty" and said that the book had the important message of the

readers' "profound right to be happy".

Former Rand business partner and lover

Nathaniel Branden has expressed differing views of

Atlas Shrugged.

He was initially quite favorable to it, and even after he and Rand

ended their relationship, he still referred to it in an interview as

"the greatest novel that has ever been written", although he found "a

few things one can quarrel with in the book". However, in 1984 he argued that

Atlas Shrugged

"encourages emotional repression and self-disowning" and that Rand's

works contained contradictory messages. He criticized the potential

psychological impact of the novel, stating that John Galt's

recommendation to respond to wrongdoing with "contempt and moral

condemnation" clashes with the view of psychologists who say this only

causes the wrongdoing to repeat itself.

The

Austrian School economist

Ludwig von Mises admired the unapologetic

elitism

he saw in Rand's work. In a letter to Rand written a few months after

the novel's publication, he said it offered "a cogent analysis of the

evils that plague our society, a substantiated rejection of the ideology

of our self-styled 'intellectuals' and a pitiless unmasking of the

insincerity of the policies adopted by governments and political

parties ... You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician

told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions

which you simply take for granted you owe to the efforts of men who are

better than you."

In the years immediately following the novel's publication, many

American conservatives, such as

William F. Buckley, Jr., strongly disapproved of Rand and her Objectivist message. In addition to the strongly critical review by Whittaker Chambers, Buckley solicited a number of critical pieces:

Russell Kirk called Objectivism an "inverted religion",

Frank Meyer accused Rand of "calculated cruelties" and her message, an "arid subhuman image of man", and

Garry Wills regarded Rand a "fanatic".

In the late 2000s, however, conservative commentators suggested the

book as a warning against a socialistic reaction to the finance crisis.

Conservative commentators

Neal Boortz,

Glenn Beck, and

Rush Limbaugh offered praise of the book on their respective radio and television programs. In 2006,

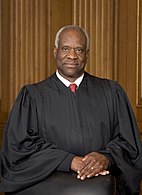

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Clarence Thomas cited

Atlas Shrugged as among his favorite novels.

Republican Congressman

John Campbell said, for example, "People are starting to feel like

we're living through the scenario that happened in [the novel] ... We're

living in

Atlas Shrugged", echoing

Stephen Moore in an article published in

The Wall Street Journal on January 9, 2009, titled "

Atlas Shrugged From Fiction to Fact in 52 Years".

In 2005, Republican Congressman

Paul Ryan said that Rand was "the reason I got into public service", and he later required his staff members to read

Atlas Shrugged. In April 2012, he disavowed such beliefs however, calling them "an urban legend", and rejected Rand's philosophy. Ryan was subsequently mocked by

Nobel Prize-winning

economist and liberal commentator

Paul Krugman for reportedly getting ideas about

monetary policy from the novel. In another commentary, Krugman quoted a quip by writer

John Rogers: "There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year-old's life:

The Lord of the Rings and

Atlas Shrugged.

One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession

with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted,

socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The

other, of course, involves

orcs."

References to

Atlas Shrugged have appeared in a variety of other popular entertainments. In the first season of the drama series

Mad Men,

Bert Cooper urges

Don Draper

to read the book, and Don's sales pitch tactic to a client indicates he

has been influenced by the strike plot: "If you don't appreciate my

hard work, then I will take it away and we'll see how you do." Less positive mentions of the novel occur in the animated comedy

Futurama, where it appears among the library of books flushed down to the sewers to be read only by grotesque mutants, and in

South Park, where a newly literate character gives up on reading after experiencing

Atlas Shrugged.

BioShock, a critically acclaimed 2007 video game, is widely considered to be a response to

Atlas Shrugged.

The story depicts a collapsed Objectivist society, and significant

characters in the game owe their naming to Rand's work, which game

creator

Ken Levine said he found "really fascinating".

In 2013, it was announced that Galt's Gulch, Chile, a settlement

for libertarian devotees named for John Galt's safe haven, would be

established near

Santiago,

Chile, but the project collapsed amid accusations of fraud and lawsuits filed by investors.

Film and television adaptations

A film adaptation of

Atlas Shrugged was in "

development hell" for nearly 40 years. In 1972,

Albert S. Ruddy

approached Rand to produce a cinematic adaptation. Rand insisted on

having final script approval, which Ruddy refused to give her, thus

preventing a deal. In 1978, Henry and Michael Jaffe negotiated a deal

for an eight-hour

Atlas Shrugged television miniseries on

NBC. Michael Jaffe hired screenwriter

Stirling Silliphant to adapt the novel and he obtained approval from Rand on the final script. However, when

Fred Silverman became president of NBC in 1979, the project was scrapped.

Rand, a former Hollywood screenwriter herself, began writing her

own screenplay, but died in 1982 with only one-third of it finished. She

left her estate, including the film rights to

Atlas, to her student

Leonard Peikoff, who sold an

option to

Michael Jaffe and

Ed Snider.

Peikoff would not approve the script they wrote, and the deal fell

through. In 1992, investor John Aglialoro bought an option to produce

the film, paying Peikoff over $1 million for full creative control.

Atlas Shrugged: Part I

In May 2010,

Brian Patrick O'Toole and Aglialoro wrote a screenplay, intent on filming in June 2010.

Stephen Polk was set to direct. However, Polk was fired and principal photography began on June 13, 2010, under the direction of

Paul Johansson and produced by Harmon Kaslow and Aglialoro.

This resulted in Aglialoro's retention of his rights to the property,

which were set to expire on June 15, 2010. Filming was completed on July

20, 2010, and the movie was released on April 15, 2011. Dagny Taggart was played by

Taylor Schilling and Hank Rearden by

Grant Bowler.

The film was met with a generally negative reception from

professional critics, getting an 11% (rotten) rating on movie review

aggregator

Rotten Tomatoes, and had less than $5 million in total box office receipts. The film earned an additional $5M in DVD and Blu-ray sales, for a total of about half of its $20M budget. The producer and screenwriter

John Aglialoro

blamed critics for the film's paltry box office take and said he might

go on strike, but ultimately went on to make the next two installments.

Atlas Shrugged: Part II

On February 2, 2012, Kaslow and Aglialoro announced

Atlas Shrugged: Part II was fully funded and that principal photography was tentatively scheduled to commence in early April 2012. The film was released on October 12, 2012,

without a special screening for critics. It suffered one of the worst

openings ever among films in wide release: it was 98th worst according

to

Box Office Mojo.

Final box office take was $3.3 million, well under that of Part I

despite the doubling of the budget to $20 million according to

The Daily Caller.

Those figures should be treated as tentative as the Internet Movie

Database estimates Part 1 budget at $20 million and the Part II budget

at $10 million, while Box Office Mojo says Part 1 cost $20 million and

Part 2 data are "NA". Critics gave the film a 5% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 21 reviews.

Atlas Shrugged: Part III: Who Is John Galt?