A scene from Peter of Verona's life: a mute man is miraculously healed. Detail from the relief on the back side of Peter of Verona's grave in the Portinari Chapel in Basilica of Sant'Eustorgio in Milan, Italy.

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice.

Believers assert that the healing of disease and disability can be

brought about by religious faith through prayer and/or other rituals

that, according to adherents, can stimulate a divine presence and power. Religious belief in divine intervention does not depend on empirical evidence that faith healing achieves an evidence-based outcome.

Claims "attributed to a myriad of techniques" such as prayer,

divine intervention, or the ministrations of an individual healer can

cure illness have been popular throughout history.

There have been claims that faith can cure blindness, deafness, cancer,

AIDS, developmental disorders, anemia, arthritis, corns, defective

speech, multiple sclerosis, skin rashes, total body paralysis, and

various injuries.

Recoveries have been attributed to many techniques commonly classified

as faith healing. It can involve prayer, a visit to a religious shrine,

or simply a strong belief in a supreme being.

Many people interpret the Bible, especially the New Testament, as teaching belief in, and the practice of, faith healing. According to a 2004 Newsweek

poll, 72 percent of Americans said they believe that praying to God can

cure someone, even if science says the person has an incurable disease. Unlike faith healing, advocates of spiritual healing make no attempt to seek divine intervention, instead believing in divine energy. The increased interest in alternative medicine

at the end of the 20th century has given rise to a parallel interest

among sociologists in the relationship of religion to health.

Virtually all scientists and philosophers dismiss faith healing as pseudoscience. Faith healing can be classified as a spiritual, supernatural, or paranormal topic, and, in some cases, belief in faith healing can be classified as magical thinking. The American Cancer Society states "available scientific evidence does not support claims that faith healing can actually cure physical ailments".

"Death, disability, and other unwanted outcomes have occurred when

faith healing was elected instead of medical care for serious injuries

or illnesses."

When parents have practiced faith healing rather than medical care,

many children have died that otherwise would have been expected to live. Similar results are found in adults.

In various belief systems

Christianity

Overview

Faith healing by Fr. Joey Faller, Pulilan, Bulacan, Philippines

Faith healing by Fernando Suarez, Philippines

Regarded as a Christian belief that God heals people through the power of the Holy Spirit, faith healing often involves the laying on of hands.

It is also called supernatural healing, divine healing, and miracle

healing, among other things. Healing in the Bible is often associated

with the ministry of specific individuals including Elijah, Jesus and Paul.

Christian physician Reginald B. Cherry views faith healing as a

pathway of healing in which God uses both the natural and the

supernatural to heal. Being healed has been described as a privilege of accepting Christ's redemption on the cross. Pentecostal writer Wilfred Graves, Jr. views the healing of the body as a physical expression of salvation. Matthew 8:17, after describing Jesus exorcising at sunset and healing all of the sick who were brought to him, quotes these miracles as a fulfillment of the prophecy in Isaiah 53:5: "He took up our infirmities and carried our diseases".

Even those Christian writers who believe in faith healing do not

all believe that one's faith presently brings about the desired healing.

"[Y]our faith does not effect your healing now. When you are healed

rests entirely on what the sovereign purposes of the Healer are."

Larry Keefauver cautions against allowing enthusiasm for faith healing

to stir up false hopes. "Just believing hard enough, long enough or

strong enough will not strengthen you or prompt your healing. Doing

mental gymnastics to 'hold on to your miracle' will not cause your

healing to manifest now."

Those who actively lay hands on others and pray with them to be healed

are usually aware that healing may not always follow immediately.

Proponents of faith healing say it may come later, and it may not come

in this life. "The truth is that your healing may manifest in eternity,

not in time".

New Testament

Parts of the four gospels in the New Testament say that Jesus

cured physical ailments well outside the capacity of first-century

medicine. One example is the case of "a woman who had had a discharge of

blood for twelve years, and who had suffered much under many

physicians, and had spent all that she had, and was not better but

rather grew worse". After healing her, Jesus tells her "Daughter, your faith has made you well. Go in peace! Be cured from your illness". At least two other times Jesus credited the sufferer's faith as the means of being healed: Mark 10:52 and Luke 19:10.

Jesus endorsed the use of the medical assistance of the time (medicines of oil and wine) when he told the parable of the Good Samaritan

(Luke 10:25-37), who "bound up [an injured man's] wounds, pouring on

oil and wine" (verse 34) as a physician would. Jesus then told the

doubting teacher of the law (who had elicited this parable by his

self-justifying question, "And who is my neighbor?" in verse 29) to "go,

and do likewise" in loving others with whom he would never ordinarily

associate (verse 37).

The healing in the gospels is referred to as a "sign" to prove Jesus' divinity and to foster belief in him as the Christ. However, when asked for other types of miracles, Jesus refused some but granted others in consideration of the motive of the request. Some theologians' understanding is that Jesus healed all who were present every single time. Sometimes he determines whether they had faith that he would heal them.

Jesus told his followers to heal the sick and stated that signs

such as healing are evidence of faith. Jesus also told his followers to

"cure sick people, raise up dead persons, make lepers clean, expel

demons. You received free, give free".

Jesus sternly ordered many who received healing from him: "Do not tell anyone!"

Jesus did not approve of anyone asking for a sign just for the

spectacle of it, describing such as coming from a "wicked and adulterous

generation".

The apostle Paul believed healing is one of the special gifts of the Holy Spirit, and that the possibility exists that certain persons may possess this gift to an extraordinarily high degree.

In the New Testament Epistle of James,

the faithful are told that to be healed, those who are sick should call

upon the elders of the church to pray over [them] and anoint [them]

with oil in the name of the Lord.

The New Testament says that during Jesus' ministry and after his Resurrection, the apostles healed the sick and cast out demons, made lame men walk, raised the dead and performed other miracles.

Jesus used miracles to convince people that he was inaugurating

the Messianic Age. as in Mt 12.28. Scholars have described Jesus'

miracles as establishing the kingdom during his lifetime.

Pentecostalism/Charismatic movement

Richard Rossi prays for the sick at one of his faith healing services, September, 1990.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the new Pentecostal movement drew participants from the Holiness movement

and other movements in America that already believed in divine healing.

By the 1930s, several faith healers drew large crowds and established

worldwide followings.

The first Pentecostals in the modern sense appeared in Topeka, Kansas, in a Bible school conducted by Charles Fox Parham, a holiness teacher and former Methodist pastor. Pentecostalism achieved worldwide attention in 1906 through the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles led by William Joseph Seymour.

Smith Wigglesworth was also a well-known figure in the early part of the 20th century. A former English plumber turned evangelist

who lived simply and read nothing but the Bible from the time his wife

taught him to read, Wigglesworth traveled around the world preaching

about Jesus and performing faith healings. Wigglesworth claimed to raise

several people from the dead in Jesus' name in his meetings.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Aimee Semple McPherson was a controversial faith healer of growing popularity during the Great Depression. Subsequently, William M. Branham has been credited as the initiater of the post-World War II healing revivals.

The healing revival he began led many to emulate his style and spawned a

generation of faith healers. Because of this, Branham has been

recognized as the "father of modern faith healers".

According to writer and researcher Patsy Sims, "the power of a Branham

service and his stage presence remains a legend unparalleled in the

history of the Charismatic movement". By the late 1940s, Oral Roberts, who was associated with and promoted by Branham's Voice of Healing magazine also became well known, and he continued with faith healing until the 1980s.

Roberts discounted faith healing in the late 1950s, stating, "I never

was a faith healer and I was never raised that way. My parents believed

very strongly in medical science and we have a doctor who takes care of

our children when they get sick. I cannot heal anyone – God does that." A friend of Roberts was Kathryn Kuhlman, another popular faith healer, who gained fame in the 1950s and had a television program on CBS. Also in this era, Jack Coe and A. A. Allen were faith healers who traveled with large tents for large open-air crusades.

Oral Roberts's successful use of television as a medium to gain a wider audience led others to follow suit. His former pilot, Kenneth Copeland, started a healing ministry. Pat Robertson, Benny Hinn, and Peter Popoff became well-known televangelists who claimed to heal the sick. Richard Rossi is known for advertising his healing clinics through secular television and radio. Kuhlman influenced Benny Hinn, who adopted some of her techniques and wrote a book about her.

Catholicism

The Roman Catholic Church recognizes two "not mutually exclusive" kinds of healing, one justified by science and one justified by faith:

- healing by human "natural means [...] through the practice of medicine" which emphasizes that the theological virtue of "charity demands that we not neglect natural means of healing people who are ill" and the cardinal virtue of prudence forewarns not "to employ a technique that has no scientific support (or even plausibility)"

- healing by divine grace "interceded on behalf of the sick through the invocation of the name of the Lord Jesus, asking for healing through the power of the Holy Spirit, whether in the form of the sacramental laying on of hands and anointing with oil or of simple prayers for healing, which often include an appeal to the saints for their aid"

In 2000, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued "Instruction on prayers for healing" with specific norms about prayer meetings for obtaining healing, which presents the Catholic Church's doctrines of sickness and healing.

It accepts "that there may be means of natural healing that have not yet been understood or recognized by science",

but it rejects superstitious practices which are neither compatible

with Christian teaching nor compatible with scientific evidence.

Faith healing is reported by Catholics as the result of intercessory prayer to a saint or to a person with the gift of healing. According to U.S. Catholic

magazine, "Even in this skeptical, postmodern, scientific age—miracles

really are possible." Three-fourths of American Catholics say they pray

for miracles.

According to John Cavadini, when healing is granted, "The miracle

is not primarily for the person healed, but for all people, as a sign

of God's work in the ultimate healing called 'salvation', or a sign of

the kingdom that is coming." Some might view their own healing as a sign

they are particularly worthy or holy, while others do not deserve it.

The Catholic Church has a special Congregation dedicated to the

careful investigation of the validity of alleged miracles attributed to

prospective saints. Pope Francis tightened the rules on money and

miracles in the canonization process.

Since Catholic Christians believe the lives of canonized saints in the

Church will reflect Christ's, many have come to expect healing miracles.

While the popular conception of a miracle can be wide-ranging, the

Catholic Church has a specific definition for the kind of miracle

formally recognized in a canonization process.

According to Catholic Encyclopedia, it is often said that cures at shrines and during Christian pilgrimages are mainly due to psychotherapy — partly to confident trust in Divine providence, and partly to the strong expectancy of cure that comes over suggestible persons at these times and places.

Among the best-known accounts by Catholics of faith healings are

those attributed to the miraculous intercession of the apparition of the

Blessed Virgin Mary known as Our Lady of Lourdes at the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes in France and the remissions of life-threatening disease claimed by those who have applied for aid to Saint Jude, who is known as the "patron saint of lost causes".

As of 2004, Catholic medics have asserted that there have been 67 miracles and 7,000 unexplainable medical cures at Lourdes since 1858.

In a 1908 book, it says these cures were subjected to intense medical

scrutiny and were only recognized as authentic spiritual cures after a

commission of doctors and scientists, called the Lourdes Medical Bureau, had ruled out any physical mechanism for the patient's recovery.

Christian Science

Christian Science claims that healing is possible through an understanding of the underlying spiritual perfection of God's creation.

The world as humanly perceived is believed to be a distortion of

spiritual reality. Christian Scientists believe that healing through

prayer is possible insofar as it succeeds in correcting the distortion.

Christian Scientists believe that prayer does not change the spiritual

creation but gives a clearer view of it, and the result appears in the

human scene as healing: the human picture adjusts to coincide more

nearly with the divine reality. Prayer works through love: the recognition of God's creation as spiritual, intact, and inherently lovable.

An important point in Christian Science is that effectual prayer

and the moral regeneration of one's life go hand-in-hand: that "signs

and wonders are wrought in the metaphysical healing of physical disease;

but these signs are only to demonstrate its divine origin, to attest

the reality of the higher mission of the Christ-power to take away the

sins of the world."

Christian Science teaches that disease is mental, a mortal fear, a

mistaken belief or conviction of the necessity and power of ill-health –

an ignorance of God's power and goodness. The chapter "Prayer" in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures

gives a full account of healing through prayer, while the testimonies

at the end of the book are written by people who believe they have been

healed through spiritual understanding gained from reading the book.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

(LDS) has had a long history of faith healings. Many members of the LDS

Church have told their stories of healing within the LDS publication,

the Ensign. The church believes healings come most often as a result of priesthood blessings

given by the laying on of hands; however, prayer often accompanied with

fasting is also thought to cause healings. Healing is always attributed

to be God's power. Latter-day Saints believe that the Priesthood of

God, held by prophets (such as Moses) and worthy disciples of the

Savior, was restored via heavenly messengers to the first prophet of

this dispensation, Joseph Smith.

According to LDS doctrine, even though members may have the restored priesthood authority to heal in the name of Jesus Christ, all efforts should be made to seek the appropriate medical help. Brigham Young stated this effectively, while also noting that the ultimate outcome is still dependent on the will of God.

If we are sick, and ask the Lord to heal us, and to do all for us that is necessary to be done, according to my understanding of the Gospel of salvation, I might as well ask the Lord to cause my wheat and corn to grow, without my plowing the ground and casting in the seed. It appears consistent to me to apply every remedy that comes within the range of my knowledge, and to ask my Father in Heaven, in the name of Jesus Christ, to sanctify that application to the healing of my body.

But suppose we were traveling in the mountains, ... and one or two were taken sick, without anything in the world in the shape of healing medicine within our reach, what should we do? According to my faith, ask the Lord Almighty to … heal the sick. This is our privilege, when so situated that we cannot get anything to help ourselves. Then the Lord and his servants can do all. But it is my duty to do, when I have it in my power.

We lay hands on the sick and wish them to be healed, and pray the Lord to heal them, but we cannot always say that he will.

Islam

Konkhogin Haokip has claimed some Muslims believe that the Quran

was sent not only as a revelation, but as a medicine, and that they

believe the Quran heals any physical and spiritual ailments through such

practices as:

- Reciting the Quran over water or olive oil and drinking, bathing or anointing oneself with it.

- Placing the right hand on a place that is in pain, or placing the right hand on the forehead and reciting Sura Al-Fatiha. These methods are referred to as ruqyah.

Scientology

Some critics of Scientology have referred to some of its practices as being similar to faith healing, based on claims made by L. Ron Hubbard in Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health and other writings.

Scientific investigation

Nearly all scientists dismiss faith healing as pseudoscience.

Some opponents of the pseudoscience label assert that faith healing

makes no scientific claims and thus should be treated as a matter of

faith that is not testable by science.

Critics reply that claims of medical cures should be tested

scientifically because, although faith in the supernatural is not in

itself usually considered to be the purview of science, claims of reproducible effects are nevertheless subject to scientific investigation.

Scientists and doctors generally find that faith healing lacks biological plausibility or epistemic warrant, which is one of the criteria to used to judge whether clinical research is ethical and financially justified. A Cochrane review

of intercessory prayer found "although some of the results of

individual studies suggest a positive effect of intercessory prayer, the

majority do not".

The authors concluded: "We are not convinced that further trials of

this intervention should be undertaken and would prefer to see any

resources available for such a trial used to investigate other questions

in health care".

A review in 1954 investigated spiritual healing, therapeutic touch

and faith healing. Of the hundred cases reviewed, none revealed that

the healer's intervention alone resulted in any improvement or cure of a

measurable organic disability.

In addition, at least one study has suggested that adult

Christian Scientists, who generally use prayer rather than medical care,

have a higher death rate than other people of the same age.

The Global Medical Research Institute (GMRI) was created in 2012

to start collecting medical records of patients who claim to have

received a supernatural healing miracle as a result of Christian

Spiritual Healing practices. The organization has a panel of medical

doctors who review the patient’s records looking at entries prior to the

claimed miracles and entries after the miracle was claimed to have

taken place. “The overall goal of GMRI is to promote an empirically

grounded understanding of the physiological, emotional, and sociological

effects of Christian Spiritual Healing practices”. This is accomplished by applying the same rigorous standards used in other forms of medical and scientific research.

Criticism

I have visited Lourdes in France and Fatima in Portugal, healing shrines of the Christian Virgin Mary. I have also visited Epidaurus in Greece and Pergamum in Turkey, healing shrines of the pagan god Asklepios. The miraculous healings recorded in both places were remarkably the same. There are, for example, many crutches hanging in the grotto of Lourdes, mute witness to those who arrived lame and left whole. There are, however, no prosthetic limbs among them, no witnesses to paraplegics whose lost limbs were restored. —John Dominic Crossan

Skeptics of faith healing offer primarily two explanations for

anecdotes of cures or improvements, relieving any need to appeal to the

supernatural. The first is post hoc ergo propter hoc, meaning that a genuine improvement or spontaneous remission

may have been experienced coincidental with but independent from

anything the faith healer or patient did or said. These patients would

have improved just as well even had they done nothing. The second is the

placebo

effect, through which a person may experience genuine pain relief and

other symptomatic alleviation. In this case, the patient genuinely has

been helped by the faith healer or faith-based remedy, not through any

mysterious or numinous function, but by the power of their own belief

that they would be healed.

In both cases the patient may experience a real reduction in symptoms,

though in neither case has anything miraculous or inexplicable occurred.

Both cases, however, are strictly limited to the body's natural

abilities.

According to the American Cancer Society:

... available scientific evidence does not support claims that faith healing can actually cure physical ailments... One review published in 1998 looked at 172 cases of deaths among children treated by faith healing instead of conventional methods. These researchers estimated that if conventional treatment had been given, the survival rate for most of these children would have been more than 90 percent, with the remainder of the children also having a good chance of survival. A more recent study found that more than 200 children had died of treatable illnesses in the United States over the past thirty years because their parents relied on spiritual healing rather than conventional medical treatment.

The American Medical Association considers that prayer as therapy should not be a medically reimbursable or deductible expense.

Belgian philosopher and skeptic Etienne Vermeersch coined the term Lourdes effect as a criticism of the magical thinking and placebo effect

possibilities for the claimed miraculous cures as there are no

documented events where a severed arm has been reattached through faith

healing at Lourdes. Vermeersch identifies ambiguity and equivocal nature

of the miraculous cures as a key feature of miraculous events.

Negative impact on public health

Reliance

on faith healing to the exclusion of other forms of treatment can have a

public health impact when it reduces or eliminates access to modern

medical techniques. This is evident in both higher mortality rates for children and in reduced life expectancy for adults.

Critics have also made note of serious injury that has resulted from

falsely labelled "healings", where patients erroneously consider

themselves cured and cease or withdraw from treatment.

For example, at least six people have died after faith healing by their

church and being told they had been healed of HIV and could stop taking

their medications. It is the stated position of the AMA that "prayer as therapy should not delay access to traditional medical care". Choosing faith healing while rejecting modern medicine can and does cause people to die needlessly.

Christian theological criticism of faith healing

Christian theological criticism of faith healing broadly falls into two distinct levels of disagreement.

The first is widely termed the "open-but-cautious" view of the

miraculous in the church today. This term is deliberately used by Robert L. Saucy in the book Are Miraculous Gifts for Today?. Don Carson is another example of a Christian teacher who has put forward what has been described as an "open-but-cautious" view. In dealing with the claims of Warfield, particularly "Warfield's insistence that miracles ceased",

Carson asserts, "But this argument stands up only if such miraculous

gifts are theologically tied exclusively to a role of attestation; and

that is demonstrably not so."

However, while affirming that he does not expect healing to happen

today, Carson is critical of aspects of the faith healing movement,

"Another issue is that of immense abuses in healing practises.... The

most common form of abuse is the view that since all illness is directly

or indirectly attributable to the devil and his works, and since Christ

by his cross has defeated the devil, and by his Spirit has given us the

power to overcome him, healing is the inheritance right of all true

Christians who call upon the Lord with genuine faith."

The second level of theological disagreement with Christian faith healing goes further. Commonly referred to as cessationism, its adherents either claim that faith healing will not happen today at all, or may happen today, but it would be unusual. Richard Gaffin argues for a form of cessationism in an essay alongside Saucy's in the book Are Miraculous Gifts for Today? In his book Perspectives on Pentecost

Gaffin states of healing and related gifts that "the conclusion to be

drawn is that as listed in 1 Corinthians 12(vv. 9f., 29f.) and

encountered throughout the narrative in Acts, these gifts, particularly

when exercised regularly by a given individual, are part of the

foundational structure of the church... and so have passed out of the

life of the church."

Gaffin qualifies this, however, by saying "At the same time, however,

the sovereign will and power of God today to heal the sick, particularly

in response to prayer (see e.g. James 5:14,15), ought to be

acknowledged and insisted on."

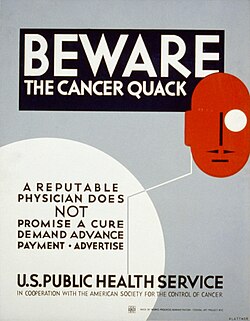

Fraud

Skeptics of

faith healers point to fraudulent practices either in the healings

themselves (such as plants in the audience with fake illnesses), or

concurrent with the healing work supposedly taking place and claim that

faith healing is a quack

practice in which the "healers" use well known non-supernatural

illusions to exploit credulous people in order to obtain their

gratitude, confidence and money. James Randi's The Faith Healers investigates Christian evangelists such as Peter Popoff,

who claimed to heal sick people on stage in front of an audience.

Popoff pretended to know private details about participants' lives by

receiving radio transmissions from his wife who was off-stage and had

gathered information from audience members prior to the show. According to this book, many of the leading modern evangelistic healers have engaged in deception and fraud. The book also questioned how faith healers use funds that were sent to them for specific purposes. Physicist Robert L. Park and doctor and consumer advocate Stephen Barrett have called into question the ethics of some exorbitant fees.

There have also been legal controversies. For example, in 1955 at a Jack Coe revival service in Miami, Florida, Coe told the parents of a three-year-old boy that he healed their son who had polio. Coe then told the parents to remove the boy's leg braces. However, their son was not cured of polio and removing the braces left the boy in constant pain. As a result, through the efforts of Joseph L. Lewis, Coe was arrested and charged on February 6, 1956 with practicing medicine without a license, a felony in the state of Florida. A Florida Justice of the Peace dismissed the case on grounds that Florida exempts divine healing from the law. Later that year Coe was diagnosed with bulbar polio, and died a few weeks later at Dallas' Parkland Hospital on December 17, 1956.

Miracles for sale

TV personality Derren Brown

produced a show on faith healing entitled "Miracles for sale" which

arguably exposed the art of faith healing as a scam. In this show,

Derren trained a scuba diver trainer picked from the general public to

be a faith healer and took him to Texas to successfully deliver a faith

healing session to a congregation.

United States law

The 1974 Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) required states to grant religious exemptions to child neglect and child abuse laws in order to receive federal money. The CAPTA amendments of 1996 42 U.S.C. § 5106i state:

(a) In General. – Nothing in this Act shall be construed –

"(1) as establishing a Federal requirement that a parent or legal guardian provide a child any medical service or treatment against the religious beliefs of the parent or legal guardian; and "(2) to require that a State find, or to prohibit a State from finding, abuse or neglect in cases in which a parent or legal guardian relies solely or partially upon spiritual means rather than medical treatment, in accordance with the religious beliefs of the parent or legal guardian.

"(b) State Requirement. – Notwithstanding subsection (a), a State shall, at a minimum, have in place authority under State law to permit the child protective services system of the State to pursue any legal remedies, including the authority to initiate legal proceedings in a court of competent jurisdiction, to provide medical care or treatment for a child when such care or treatment is necessary to prevent or remedy serious harm to the child, or to prevent the withholding of medically indicated treatment from children with life threatening conditions. Except with respect to the withholding of medically indicated treatments from disabled infants with life threatening conditions, case by case determinations concerning the exercise of the authority of this subsection shall be within the sole discretion of the State.

Thirty-one states have child-abuse religious exemptions. These are

Alabama, Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia,

Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine,

Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New

Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania,

Vermont, Virginia, and Wyoming.

In six of these states, Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Ohio and

Virginia, the exemptions extend to murder and manslaughter. Of these,

Idaho is the only state accused of having a large number of deaths due

to the legislation in recent times.

In February 2015, controversy was sparked in Idaho over a bill believed

to further reinforce parental rights to deny their children medical

care.

Reckless homicide convictions

Parents

have been convicted of child abuse and felony reckless negligent

homicide and found responsible for killing their children when they

withheld lifesaving medical care and chose only prayers.