The history of competition law reaches back to the Roman Empire. The business practices of market traders, guilds

and governments have always been subject to scrutiny, and sometimes

severe sanctions. Since the 20th century, competition law has become

global. The two largest and most influential systems of competition regulation are United States antitrust law and European Union competition law. National and regional competition authorities across the world have formed international support and enforcement networks.

Modern competition law has historically evolved on a country level to promote and maintain fair competition in markets principally within the territorial boundaries of nation-states. National competition law usually does not cover activity beyond territorial borders unless it has significant effects at nation-state level. Countries may allow for extraterritorial jurisdiction in competition cases based on so-called effects doctrine. The protection of international competition is governed by international competition agreements. In 1945, during the negotiations preceding the adoption of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, limited international competition obligations were proposed within the Charter for an International Trade Organisation. These obligations were not included in GATT, but in 1994, with the conclusion of the Uruguay Round of GATT Multilateral Negotiations, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was created. The Agreement Establishing the WTO included a range of limited provisions on various cross-border competition issues on a sector specific basis.

Modern competition law has historically evolved on a country level to promote and maintain fair competition in markets principally within the territorial boundaries of nation-states. National competition law usually does not cover activity beyond territorial borders unless it has significant effects at nation-state level. Countries may allow for extraterritorial jurisdiction in competition cases based on so-called effects doctrine. The protection of international competition is governed by international competition agreements. In 1945, during the negotiations preceding the adoption of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, limited international competition obligations were proposed within the Charter for an International Trade Organisation. These obligations were not included in GATT, but in 1994, with the conclusion of the Uruguay Round of GATT Multilateral Negotiations, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was created. The Agreement Establishing the WTO included a range of limited provisions on various cross-border competition issues on a sector specific basis.

Principle

Competition law, or antitrust law, has three main elements:

- prohibiting agreements or practices that restrict free trading and competition between business. This includes in particular the repression of free trade caused by cartels.

- banning abusive behavior by a firm dominating a market, or anti-competitive practices that tend to lead to such a dominant position. Practices controlled in this way may include predatory pricing, tying, price gouging, refusal to deal, and many others.

- supervising the mergers and acquisitions of large corporations, including some joint ventures. Transactions that are considered to threaten the competitive process can be prohibited altogether, or approved subject to "remedies" such as an obligation to divest part of the merged business or to offer licenses or access to facilities to enable other businesses to continue competing.

Substance and practice of competition law varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Protecting the interests of consumers (consumer welfare) and ensuring that entrepreneurs have an opportunity to compete in the market economy

are often treated as important objectives. Competition law is closely

connected with law on deregulation of access to markets, state aids and

subsidies, the privatization

of state owned assets and the establishment of independent sector

regulators, among other market-oriented supply-side policies. In recent

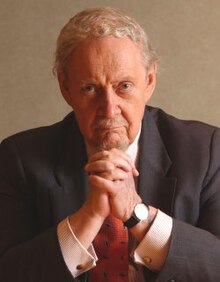

decades, competition law has been viewed as a way to provide better public services. Robert Bork

argued that competition laws can produce adverse effects when they

reduce competition by protecting inefficient competitors and when costs

of legal intervention are greater than benefits for the consumers.

History

Roman legislation

An early example was enacted during the Roman Republic around 50 BC. To protect the grain trade, heavy fines were imposed on anyone directly, deliberately, and insidiously stopping supply ships. Under Diocletian in 301 A.D., an edict

imposed the death penalty for anyone violating a tariff system, for

example by buying up, concealing, or contriving the scarcity of everyday

goods. More legislation came under the constitution of Zeno of 483 A.D., which can be traced into Florentine municipal laws of 1322 and 1325. This provided for confiscation of property and banishment for any trade combination or joint action of monopolies private or granted by the Emperor. Zeno rescinded all previously granted exclusive rights. Justinian I subsequently introduced legislation to pay officials to manage state monopolies.

Middle Ages

Legislation in England to control monopolies and restrictive practices was in force well before the Norman Conquest. The Domesday Book recorded that "foresteel" (i.e. forestalling, the practice of buying up goods before they reach market and then inflating the prices) was one of three forfeitures that King Edward the Confessor could carry out through England. But concern for fair prices also led to attempts to directly regulate the market. Under Henry III an act was passed in 1266 to fix bread and ale prices in correspondence with grain prices laid down by the assizes. Penalties for breach included amercements, pillory and tumbrel.

A 14th century statute labelled forestallers as "oppressors of the poor

and the community at large and enemies of the whole country". Under King Edward III the Statute of Labourers of 1349

fixed wages of artificers and workmen and decreed that foodstuffs

should be sold at reasonable prices. On top of existing penalties, the

statute stated that overcharging merchants must pay the injured party

double the sum he received, an idea that has been replicated in punitive treble damages under US antitrust law. Also under Edward III, the following statutory provision outlawed trade combination.

... we have ordained and established, that no merchant or other shall make Confederacy, Conspiracy, Coin, Imagination, or Murmur, or Evil Device in any point that may turn to the Impeachment, Disturbance, Defeating or Decay of the said Staples, or of anything that to them pertaineth, or may pertain.

In continental Europe, competition principles developed in lex mercatoria. Examples of legislation enshrining competition principles include the constitutiones juris metallici by Wenceslaus II of Bohemia

between 1283 and 1305, condemning combination of ore traders increasing

prices; the Municipal Statutes of Florence in 1322 and 1325 followed Zeno's legislation against state monopolies; and under Emperor Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire

a law was passed "to prevent losses resulting from monopolies and

improper contracts which many merchants and artisans made in the

Netherlands". In 1553, Henry VIII of England

reintroduced tariffs for foodstuffs, designed to stabilize prices, in

the face of fluctuations in supply from overseas. So the legislation

read here that whereas,

... it is very hard and difficult to put certain prices to any such things ... [it is necessary because] prices of such victuals be many times enhanced and raised by the Greedy Covetousness and Appetites of the Owners of such Victuals, by occasion of ingrossing and regrating the same, more than upon any reasonable or just ground or cause, to the great damage and impoverishing of the King's subjects.

Around this time organizations representing various tradesmen and handicrafts people, known as guilds

had been developing, and enjoyed many concessions and exemptions from

the laws against monopolies. The privileges conferred were not abolished

until the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.

Early competition law in Europe

Judge Coke in the 17th century thought that general restraints on trade were unreasonable.

The English common law of restraint of trade is the direct predecessor to modern competition law later developed in the US. It is based on the prohibition of agreements that ran counter to public policy, unless the reasonableness of an agreement could be shown. It effectively prohibited agreements designed to restrain another's trade. The 1414 Dyer's

is the first known restrictive trade agreement to be examined under

English common law. A dyer had given a bond not to exercise his trade in

the same town as the plaintiff for six months but the plaintiff had

promised nothing in return. On hearing the plaintiff's attempt to

enforce this restraint, Hull J exclaimed, "per Dieu, if the plaintiff

were here, he should go to prison until he had paid a fine to the King".

The court denied the collection of a bond for the dyer's breach of

agreement because the agreement was held to be a restriction on trade.

English courts subsequently decided a range of cases which gradually

developed competition related case law, which eventually were

transformed into statute law.

Elizabeth I assured monopolies would not be abused in the early era of globalization.

Europe around the 16th century was changing quickly. The new world

had just been opened up, overseas trade and plunder was pouring wealth

through the international economy and attitudes among businessmen were

shifting. In 1561 a system of Industrial Monopoly Licenses, similar to

modern patents had been introduced into England. But by the reign of Queen Elizabeth I,

the system was reputedly much abused and used merely to preserve

privileges, encouraging nothing new in the way of innovation or

manufacture.

In response English courts developed case law on restrictive business

practices. The statute followed the unanimous decision in Darcy v. Allein 1602, also known as the Case of Monopolies, of the King's bench to declare void the sole right that Queen Elizabeth I had granted to Darcy to import playing cards into England.

Darcy, an officer of the Queen's household, claimed damages for the

defendant's infringement of this right. The court found the grant void

and that three characteristics of monopoly

were (1) price increases, (2) quality decrease, (3) the tendency to

reduce artificers to idleness and beggary. This put an end to granted

monopolies until King James I began to grant them again. In 1623 Parliament passed the Statute of Monopolies, which for the most part excluded patent rights from its prohibitions, as well as guilds. From King Charles I, through the civil war and to King Charles II, monopolies continued, especially useful for raising revenue. Then in 1684, in East India Company v. Sandys

it was decided that exclusive rights to trade only outside the realm

were legitimate, on the grounds that only large and powerful concerns

could trade in the conditions prevailing overseas.

The development of early competition law in England and Europe progressed with the diffusion of writings such as The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, who first established the concept of the market economy. At the same time industrialisation replaced the individual artisan,

or group of artisans, with paid labourers and machine-based production.

Commercial success increasingly dependent on maximising production

while minimising cost. Therefore, the size of a company became

increasingly important, and a number of European countries responded by

enacting laws to regulate large companies which restricted trade.

Following the French Revolution

in 1789 the law of 14–17 June 1791 declared agreements by members of

the same trade that fixed the price of an industry or labour as void,

unconstitutional, and hostile to liberty. Similarly the Austrian Penal

Code of 1852 established that "agreements ... to raise the price of a

commodity ... to the disadvantage of the public should be punished as

misdemeanours". Austria passed a law in 1870 abolishing the penalties,

though such agreements remained void. However, in Germany laws clearly

validated agreements between firms to raise prices. Throughout the 18th

and 19th century, ideas that dominant private companies or legal

monopolies could excessively restrict trade were further developed in

Europe. However, as in the late 19th century, a depression spread

through Europe, known as the Panic of 1873, ideas of competition lost favour, and it was felt that companies had to co-operate by forming cartels to withstand huge pressures on prices and profits.

Modern competition law

While the development of competition law stalled in Europe during the late 19th century, in 1889 Canada enacted what is considered the first competition statute of modern times. The Act for the Prevention and Suppression of Combinations formed in restraint of Trade was passed one year before the United States enacted the most famous legal statute on competition law, the Sherman Act of 1890. It was named after Senator John Sherman

who argued that the Act "does not announce a new principle of law, but

applies old and well recognised principles of common law."

United States antitrust

Senatorial Round House by Thomas Nast, 1886

The Sherman Act

of 1890 attempted to outlaw the restriction of competition by large

companies, who co-operated with rivals to fix outputs, prices and market

shares, initially through pools and later through trusts.

Trusts first appeared in the US railroads, where the capital

requirement of railroad construction precluded competitive services in

then scarcely settled territories. This trust allowed railroads to

discriminate on rates imposed and services provided to consumers and

businesses and to destroy potential competitors. Different trusts could

be dominant in different industries. The Standard Oil Company trust in the 1880s controlled a number of markets, including the market in fuel oil, lead and whiskey.

Vast numbers of citizens became sufficiently aware and publicly

concerned about how the trusts negatively impacted them that the Act

became a priority for both major parties. A primary concern of this act

is that competitive markets themselves should provide the primary

regulation of prices, outputs, interests and profits. Instead, the Act

outlawed anticompetitive practices, codifying the common law restraint

of trade doctrine.

Prof Rudolph Peritz has argued that competition law in the United

States has evolved around two sometimes conflicting concepts of

competition: first that of individual liberty, free of government

intervention, and second a fair competitive environment free of

excessive economic power.

Since the enactment of the Sherman Act enforcement of competition law

has been based on various economic theories adopted by Government.

Section 1 of the Sherman Act declared illegal "every contract, in

the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or

commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations." Section 2

prohibits monopolies,

or attempts and conspiracies to monopolize. Following the enactment in

1890 US court applies these principles to business and markets. Courts

applied the Act without consistent economic analysis until 1914, when it

was complemented by the Clayton Act

which specifically prohibited exclusive dealing agreements,

particularly tying agreements and interlocking directorates, and mergers

achieved by purchasing stock. From 1915 onwards the rule of reason

analysis was frequently applied by courts to competition cases.

However, the period was characterized by the lack of competition law

enforcement. From 1936 to 1972 courts' application of anti-trust law was

dominated by the structure-conduct-performance

paradigm of the Harvard School. From 1973 to 1991, the enforcement of

anti-trust law was based on efficiency explanations as the Chicago

School became dominant, and through legal writings such as Judge Robert Bork's book The Antitrust Paradox. Since 1992 game theory has frequently been used in anti-trust cases.

European Union law

Competition law gained new recognition in Europe in the inter-war

years, with Germany enacting its first anti-cartel law in 1923 and

Sweden and Norway adopting similar laws in 1925 and 1926 respectively.

However, with the Great Depression of 1929 competition law disappeared from Europe and was revived following the Second World War

when the United Kingdom and Germany, following pressure from the United

States, became the first European countries to adopt fully fledged

competition laws. At a regional level EU competition law has its origins in the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) agreement between France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg

and Germany in 1951 following the Second World War. The agreement aimed

to prevent Germany from re-establishing dominance in the production of coal and steel

as it was felt that this dominance had contributed to the outbreak of

the war. Article 65 of the agreement banned cartels and article 66 made

provisions for concentrations, or mergers, and the abuse of a dominant

position by companies. This was the first time that competition law principles were included in a plurilateral regional agreement and established the trans-European model of competition law. In 1957 competition rules were included in the Treaty of Rome, also known as the EC Treaty, which established the European Economic Community

(EEC). The Treaty of Rome established the enactment of competition law

as one of the main aims of the EEC through the "institution of a system

ensuring that competition in the common market is not distorted." The

two central provisions on EU competition law on companies were

established in article 85, which prohibited anti-competitive agreements,

subject to some exemptions, and article 86 prohibiting the abuse of

dominant position. The treaty also established principles on competition

law for member states, with article 90 covering public undertakings,

and article 92 making provisions on state aid. Regulations on mergers

were not included as member states could not establish consensus on the

issue at the time.

Today, the Treaty of Lisbon prohibits anti-competitive agreements in Article 101(1), including price fixing.

According to Article 101(2) any such agreements are automatically void.

Article 101(3) establishes exemptions, if the collusion is for

distributional or technological innovation, gives consumers a "fair

share" of the benefit and does not include unreasonable restraints that

risk eliminating competition anywhere (or compliant with the general principle of European Union law of proportionality). Article 102 prohibits the abuse of dominant position, such as price discrimination and exclusive dealing. Article 102 allows the European Council regulations to govern mergers between firms (the current regulation is the Regulation 139/2004/EC).

The general test is whether a concentration (i.e. merger or

acquisition) with a community dimension (i.e. affects a number of EU

member states) might significantly impede effective competition.

Articles 106 and 107 provide that member state's right to deliver

public services may not be obstructed, but that otherwise public

enterprises must adhere to the same competition principles as companies.

Article 107 lays down a general rule that the state may not aid or

subsidize private parties in distortion of free competition and provides

exemptions for charities, regional development objectives and in the event of a natural disaster.

Leading ECJ cases on competition law include Consten & Grundig v Commission and United Brands v Commission.

India

India responded positively by opening up its economy by removing controls during the Economic liberalisation. In quest of increasing the efficiency of the nation's economy, the Government of India acknowledged the Liberalization Privatization Globalization era. As a result, Indian market faces competition from within and outside the country. This led to the need of a strong legislation to dispense justice in commercial matters and the Competition Act, 2002

was passed. The history of competition law in India dates back to the

1960s when the first competition law, namely the Monopolies and

Restrictive Trade Practices Act (MRTP) was enacted in 1969. But after

the economic reforms in 1991, this legislation was found to be obsolete

in many aspects and as a result, a new competition law in the form of the Competition Act, 2002 was enacted in 2003. The Competition Commission of India, is the quasi judicial body established for enforcing provisions of the Competition Act.

International expansion

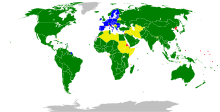

By

2008 111 countries had enacted competition laws, which is more than 50

percent of countries with a population exceeding 80,000 people. 81 of

the 111 countries had adopted their competition laws in the past 20

years, signaling the spread of competition law following the collapse of

the Soviet Union and the expansion of the European Union. Currently competition authorities

of many states closely co-operate, on everyday basis, with foreign

counterparts in their enforcement efforts, also in such key area as

information / evidence sharing.

In many of Asia's developing countries, including India, Competition law is considered a tool to stimulate economic growth. In Korea and Japan, the competition law prevents certain forms of conglomerates. In addition, competition law has promoted fairness in China and Indonesia as well as international integration in Vietnam. Hong Kong's Competition Ordinance came into force in the year 2015.

ASEAN member states

As part of the creation of the ASEAN Economic Community, the member states of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) pledged to enact competition laws and policies by the end of 2015.

Today, all ten member states have general competition legislation in

place. While there remains differences between regimes (for example,

over merger control notification rules, or leniency policies for

whistle-blowers), and it is unlikely that there will be a supranational competition authority for ASEAN (akin to the European Union), there is a clear trend towards increase in infringement investigations or decisions on cartel enforcement.

Enforcement

There is considerable controversy among WTO members, in green, whether competition law should form part of the agreements

At a national level competition law is enforced through competition authorities, as well as private enforcement. The United States Supreme Court explained:

Every violation of the antitrust laws is a blow to the free-enterprise system envisaged by Congress. This system depends on strong competition for its health and vigor, and strong competition depends, in turn, on compliance with antitrust legislation. In enacting these laws, Congress had many means at its disposal to penalize violators. It could have, for example, required violators to compensate federal, state, and local governments for the estimated damage to their respective economies caused by the violations. But, this remedy was not selected. Instead, Congress chose to permit all persons to sue to recover three times their actual damages every time they were injured in their business or property by an antitrust violation.

In the European Union, the Modernisation Regulation 1/2003 means that the European Commission is no longer the only body capable of public enforcement of European Union competition law. This was done to facilitate quicker resolution of competition-related inquiries. In 2005 the Commission issued a Green Paper on Damages actions for the breach of the EC antitrust rules, which suggested ways of making private damages claims against cartels easier.

Some EU Member States enforce their competition laws with criminal sanctions. As analysed by Professor Whelan, these types of sanctions engender a number of significant theoretical, legal and practical challenges.

Antitrust administration and legislation can be seen as a balance between:

- guidelines which are clear and specific to the courts, regulators and business but leave little room for discretion that prevents the application of laws from resulting in unintended consequences.

- guidelines which are broad, hence allowing administrators to sway between improving economic outcomes versus succumbing to political policies to redistribute wealth.

Chapter 5 of the post war Havana Charter contained an Antitrust code but this was never incorporated into the WTO's forerunner, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1947. Office of Fair Trading

Director and Professor Richard Whish wrote sceptically that it "seems

unlikely at the current stage of its development that the WTO will

metamorphose into a global competition authority." Despite that, at the ongoing Doha round of trade talks for the World Trade Organization,

discussion includes the prospect of competition law enforcement moving

up to a global level. While it is incapable of enforcement itself, the

newly established International Competition Network (ICN) is a way for national authorities to coordinate their own enforcement activities.

Theory

Classical perspective

Under the doctrine of laissez-faire,

antitrust is seen as unnecessary as competition is viewed as a

long-term dynamic process where firms compete against each other for

market dominance. In some markets a firm may successfully dominate, but

it is because of superior skill or innovativeness. However, according to

laissez-faire theorists, when it tries to raise prices to take

advantage of its monopoly position it creates profitable opportunities

for others to compete. A process of creative destruction

begins which erodes the monopoly. Therefore, government should not try

to break up monopoly but should allow the market to work.

John Stuart Mill believed the restraint of trade doctrine was justified to preserve liberty and competition.

The classical perspective on competition was that certain agreements

and business practice could be an unreasonable restraint on the individual liberty

of tradespeople to carry on their livelihoods. Restraints were judged

as permissible or not by courts as new cases appeared and in the light

of changing business circumstances. Hence the courts found specific

categories of agreement, specific clauses, to fall foul of their

doctrine on economic fairness, and they did not contrive an overarching

conception of market power. Earlier theorists like Adam Smith rejected

any monopoly power on this basis.

A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly under-stocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate.

In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith also pointed out the cartel problem, but did not advocate specific legal measures to combat them.

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary.

By the latter half of the 19th century it had become clear that large firms had become a fact of the market economy. John Stuart Mill's approach was laid down in his treatise On Liberty (1859).

Again, trade is a social act. Whoever undertakes to sell any description of goods to the public, does what affects the interest of other persons, and of society in general; and thus his conduct, in principle, comes within the jurisdiction of society... both the cheapness and the good quality of commodities are most effectually provided for by leaving the producers and sellers perfectly free, under the sole check of equal freedom to the buyers for supplying themselves elsewhere. This is the so-called doctrine of Free Trade, which rests on grounds different from, though equally solid with, the principle of individual liberty asserted in this Essay. Restrictions on trade, or on production for purposes of trade, are indeed restraints; and all restraint, qua restraint, is an evil...

Neo-classical synthesis

Paul Samuelson, author of the 20th century's most successful economics text, combined mathematical models and Keynesian

macroeconomic intervention. He advocated the general success of the

market but backed the American government's antitrust policies.

After Mill, there was a shift in economic theory, which emphasized a

more precise and theoretical model of competition. A simple

neo-classical model of free markets holds that production and

distribution of goods and services in competitive free markets maximizes

social welfare.

This model assumes that new firms can freely enter markets and compete

with existing firms, or to use legal language, there are no barriers to entry. By this term economists mean something very specific, that competitive free markets deliver allocative, productive and dynamic efficiency. Allocative efficiency is also known as Pareto efficiency after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto and means that resources in an economy over the long run will go precisely to those who are willing and able to pay for them. Because rational producers will keep producing and selling, and buyers will keep buying up to the last marginal unit

of possible output – or alternatively rational producers will be reduce

their output to the margin at which buyers will buy the same amount as

produced – there is no waste, the greatest number wants of the greatest

number of people become satisfied and utility

is perfected because resources can no longer be reallocated to make

anyone better off without making someone else worse off; society has

achieved allocative efficiency. Productive efficiency simply means that

society is making as much as it can. Free markets are meant to reward

those who work hard, and therefore those who will put society's resources towards the frontier of its possible production.

Dynamic efficiency refers to the idea that business which constantly

competes must research, create and innovate to keep its share of

consumers. This traces to Austrian-American political scientist Joseph Schumpeter's notion that a "perennial gale of creative destruction" is ever sweeping through capitalist economies, driving enterprise at the market's mercy. This led Schumpeter to argue that monopolies did not need to be broken up (as with Standard Oil) because the next gale of economic innovation would do the same.

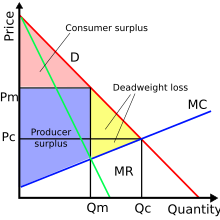

Contrasting with the allocatively, productively and dynamically

efficient market model are monopolies, oligopolies, and cartels. When

only one or a few firms exist in the market, and there is no credible

threat of the entry of competing firms, prices rise above the

competitive level, to either a monopolistic or oligopolistic equilibrium

price. Production is also decreased, further decreasing social welfare by creating a deadweight loss. Sources of this market power are said to include the existence of externalities, barriers to entry of the market, and the free rider problem. Markets may fail to be efficient for a variety of reasons, so the exception of competition law's intervention to the rule of laissez faire is justified if government failure can be avoided. Orthodox economists fully acknowledge that perfect competition is seldom observed in the real world, and so aim for what is called "workable competition." This follows the theory that if one cannot achieve the ideal, then go for the second best option by using the law to tame market operation where it can.

Chicago School

A group of economists and lawyers, who are largely associated with the University of Chicago,

advocate an approach to competition law guided by the proposition that

some actions that were originally considered to be anticompetitive could

actually promote competition. The U.S. Supreme Court has used the Chicago School approach in several recent cases. One view of the Chicago School approach to antitrust is found in United States Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner's books Antitrust Law and Economic Analysis of Law.

Robert Bork was highly critical of court decisions on United States antitrust law in a series of law review articles and his book The Antitrust Paradox. Bork argued that both the original intention of antitrust laws and economic efficiency was the pursuit only of consumer welfare, the protection of competition rather than competitors.

Furthermore, only a few acts should be prohibited, namely cartels that

fix prices and divide markets, mergers that create monopolies, and

dominant firms pricing predatorily, while allowing such practices as

vertical agreements and price discrimination on the grounds that it did

not harm consumers.

Running through the different critiques of US antitrust policy is the

common theme that government interference in the operation of free

markets does more harm than good. "The only cure for bad theory," writes Bork, "is better theory." The late Harvard Law School Professor Philip Areeda,

who favours more aggressive antitrust policy, in at least one Supreme

Court case challenged Robert Bork's preference for non-intervention.

Practice

Collusion and cartels

Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Smith was an early enemy of cartels.

Dominance and monopoly

The economist's depiction of deadweight loss to efficiency that monopolies cause

When firms hold large market shares, consumers risk paying higher

prices and getting lower quality products than compared to competitive

markets. However, the existence of a very high market share does not

always mean consumers are paying excessive prices since the threat of

new entrants to the market can restrain a high-market-share firm's price

increases. Competition law does not make merely having a monopoly

illegal, but rather abusing the power that a monopoly may confer, for

instance through exclusionary practices.

First it is necessary to determine whether a firm is dominant, or

whether it behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its

competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer." Under EU law, very large market shares raise a presumption that a firm is dominant, which may be rebuttable.

If a firm has a dominant position, then there is "a special

responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the

common market."

Similarly as with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with

reference to the particular market in which the firm and product in

question is sold. Then although the lists are seldom closed,

certain categories of abusive conduct are usually prohibited under the

country's legislation. For instance, limiting production at a shipping

port by refusing to raise expenditure and update technology could be

abusive.

Tying one product into the sale of another can be considered abuse too,

being restrictive of consumer choice and depriving competitors of

outlets. This was the alleged case in Microsoft v. Commission leading to an eventual fine of million for including its Windows Media Player with the Microsoft Windows

platform. A refusal to supply a facility which is essential for all

businesses attempting to compete to use can constitute an abuse. One

example was in a case involving a medical company named Commercial Solvents. When it set up its own rival in the tuberculosis

drugs market, Commercial Solvents were forced to continue supplying a

company named Zoja with the raw materials for the drug. Zoja was the

only market competitor, so without the court forcing supply, all

competition would have been eliminated.

Forms of abuse relating directly to pricing include price

exploitation. It is difficult to prove at what point a dominant firm's

prices become "exploitative" and this category of abuse is rarely found.

In one case however, a French funeral service was found to have

demanded exploitative prices, and this was justified on the basis that

prices of funeral services outside the region could be compared. A more tricky issue is predatory pricing.

This is the practice of dropping prices of a product so much that one's

smaller competitors cannot cover their costs and fall out of business.

The Chicago School (economics) considers predatory pricing to be unlikely. However, in France Telecom SA v. Commission

a broadband internet company was forced to pay $13.9 million for

dropping its prices below its own production costs. It had "no interest

in applying such prices except that of eliminating competitors" and was being cross-subsidized to capture the lion's share of a booming market. One last category of pricing abuse is price discrimination.

An example of this could be offering rebates to industrial customers

who export your company's sugar, but not to customers who are selling

their goods in the same market as you are in.

Mergers and acquisitions

A merger or acquisition involves, from a competition law perspective,

the concentration of economic power in the hands of fewer than before. This usually means that one firm buys out the shares

of another. The reasons for oversight of economic concentrations by the

state are the same as the reasons to restrict firms who abuse a

position of dominance, only that regulation of mergers and acquisitions

attempts to deal with the problem before it arises, ex ante prevention of market dominance.

In the United States merger regulation began under the Clayton Act, and

in the European Union, under the Merger Regulation 139/2004 (known as

the "ECMR").

Competition law requires that firms proposing to merge gain

authorization from the relevant government authority. The theory behind

mergers is that transaction costs can be reduced compared to operating

on an open market through bilateral contracts. Concentrations can increase economies of scale

and scope. However often firms take advantage of their increase in

market power, their increased market share and decreased number of

competitors, which can adversely affect the deal that consumers get.

Merger control is about predicting what the market might be like, not

knowing and making a judgment. Hence the central provision under EU law

asks whether a concentration would, if it went ahead,

"significantly impede effective competition... in particular as a result

of the creation or strengthening off a dominant position..." and the corresponding provision under US antitrust states similarly,

No person shall acquire, directly or indirectly, the whole or any part of the stock or other share capital... of the assets of one or more persons engaged in commerce or in any activity affecting commerce, where... the effect of such acquisition, of such stocks or assets, or of the use of such stock by the voting or granting of proxies or otherwise, may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.

What amounts to a substantial lessening of, or significant impediment

to competition is usually answered through empirical study. The market

shares of the merging companies can be assessed and added, although this

kind of analysis only gives rise to presumptions, not conclusions. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

is used to calculate the "density" of the market, or what concentration

exists. Aside from the maths, it is important to consider the product

in question and the rate of technical innovation in the market. A further problem of collective dominance, or oligopoly through "economic links" can arise, whereby the new market becomes more conducive to collusion.

It is relevant how transparent a market is, because a more concentrated

structure could mean firms can coordinate their behavior more easily,

whether firms can deploy deterrents and whether firms are safe from a

reaction by their competitors and consumers. The entry of new firms to the market, and any barriers that they might encounter should be considered.

If firms are shown to be creating an uncompetitive concentration, in

the US they can still argue that they create efficiencies enough to

outweigh any detriment, and similar reference to "technical and economic

progress" is mentioned in Art. 2 of the ECMR.

Another defense might be that a firm which is being taken over is about

to fail or go insolvent, and taking it over leaves a no less

competitive state than what would happen anyway. Mergers vertically in the market are rarely of concern, although in AOL/Time Warner the European Commission required that a joint venture with a competitor Bertelsmann be ceased beforehand. The EU authorities have also focused lately on the effect of conglomerate mergers,

where companies acquire a large portfolio of related products, though

without necessarily dominant shares in any individual market.

Intellectual property, innovation and competition

Competition law has become increasingly intertwined with intellectual property, such as copyright, trademarks, patents, industrial design rights and in some jurisdictions trade secrets. It is believed that promotion of innovation

through enforcement of intellectual property rights may promote as well

as limit competitiveness. The question rests on whether it is legal to

acquire monopoly through accumulation of intellectual property rights.

In which case, the judgment needs to decide between giving preference to

intellectual property rights or to competitiveness:

- Should antitrust laws accord special treatment to intellectual property.

- Should intellectual rights be revoked or not granted when antitrust laws are violated.

Concerns also arise over anti-competitive effects and consequences due to:

- Intellectual properties that are collaboratively designed with consequence of violating antitrust laws (intentionally or otherwise).

- The further effects on competition when such properties are accepted into industry standards.

- Cross-licensing of intellectual property.

- Bundling of intellectual property rights to long term business transactions or agreements to extend the market exclusiveness of intellectual property rights beyond their statutory duration.

- Trade secrets, if they remain a secret, having an eternal length of life.

Some scholars suggest that a prize instead of patent would solve the

problem of deadweight loss, when innovators got their reward from the

prize, provided by the government or non-profit organization, rather

than directly selling to the market, see Millennium Prize Problems.

However innovators may accept the prize only when it is at least as

much as how much they earn from patent, which is a question difficult to

determine.