Many researchers from the 1860s onwards attempted to find evidence for the theory, but these have all been explained away either by other mechanisms such as genetic contamination, or as fraud. On the other hand, August Weismann's experiment is now considered to have failed to disprove Lamarckism as it did not address use and disuse. Later, Mendelian genetics supplanted the notion of inheritance of acquired traits, eventually leading to the development of the modern synthesis, and the general abandonment of Lamarckism in biology. Despite this, interest in Lamarckism has continued.

Studies in the field of epigenetics, genetics and somatic hypermutation have highlighted the possible inheritance of traits acquired by the previous generation. The characterization of these findings as Lamarckism has been disputed. The inheritance of the hologenome, consisting of the genomes of all an organism's symbiotic microbes as well as its own genome, is also somewhat Lamarckian in effect, though entirely Darwinian in its mechanisms.

Early history

Origins

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck repeated the ancient folk wisdom of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

The inheritance of acquired characteristics was proposed in ancient

times, and remained a current idea for many centuries. The historian of

science Conway Zirkle wrote in 1935 that:

Lamarck was neither the first nor the most distinguished biologist to believe in the inheritance of acquired characters. He merely endorsed a belief which had been generally accepted for at least 2,200 years before his time and used it to explain how evolution could have taken place. The inheritance of acquired characters had been accepted previously by Hippocrates, Aristotle, Galen, Roger Bacon, Jerome Cardan, Levinus Lemnius, John Ray, Michael Adanson, Jo. Fried. Blumenbach and Erasmus Darwin among others.

Zirkle noted that Hippocrates described pangenesis,

the theory that what is inherited derives from the whole body of the

parent, whereas Aristotle thought it impossible; but that all the same,

Aristotle implicitly agreed to the inheritance of acquired

characteristics, giving the example of the inheritance of a scar, or of

blindness, though noting that children do not always resemble their

parents. Zirkle recorded that Pliny the Elder

thought much the same. Zirkle also pointed out that stories involving

the idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics appear numerous

times in ancient mythology and the Bible, and persisted through to Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories. Erasmus Darwin's Zoonomia (c. 1795) suggested that warm-blooded animals

develop from "one living filament... with the power of acquiring new

parts" in response to stimuli, with each round of "improvements" being

inherited by successive generations.

Darwin's pangenesis

Charles Darwin's pangenesis theory. Every part of the body emits tiny gemmules which migrate to the gonads

and contribute to the next generation via the fertilised egg. Changes

to the body during an organism's life would be inherited, as in

Lamarckism.

Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species

proposed natural selection as the main mechanism for development of

species, but did not rule out a variant of Lamarckism as a supplementary

mechanism. Darwin called this pangenesis, and explained it in the final chapter of his book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication

(1868), after describing numerous examples to demonstrate what he

considered to be the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Pangenesis, which he emphasised was a hypothesis, was based on the idea

that somatic cells would, in response to environmental stimulation (use and disuse), throw off 'gemmules' or 'pangenes' which travelled around the body, though not necessarily in the bloodstream.

These pangenes were microscopic particles that supposedly contained

information about the characteristics of their parent cell, and Darwin

believed that they eventually accumulated in the germ cells where they could pass on to the next generation the newly acquired characteristics of the parents.

Darwin's half-cousin, Francis Galton, carried out experiments on rabbits, with Darwin's cooperation, in which he transfused the blood

of one variety of rabbit into another variety in the expectation that

its offspring would show some characteristics of the first. They did

not, and Galton declared that he had disproved Darwin's hypothesis of

pangenesis, but Darwin objected, in a letter to the scientific journal Nature,

that he had done nothing of the sort, since he had never mentioned

blood in his writings. He pointed out that he regarded pangenesis as

occurring in protozoa and plants, which have no blood, as well as in animals.

Lamarck's evolutionary framework

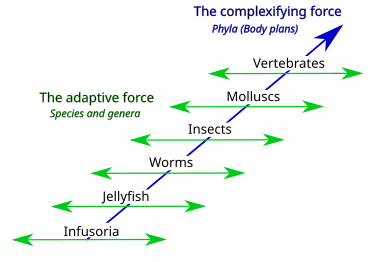

Lamarck's two-factor theory involves 1) a complexifying force that drives animal body plans towards higher levels (orthogenesis) creating a ladder of phyla, and 2) an adaptive force that causes animals with a given body plan to adapt to circumstances (use and disuse, inheritance of acquired characteristics), creating a diversity of species and genera. Popular views of Lamarckism only consider an aspect of the adaptive force.

Between 1800 and 1830, Lamarck proposed a systematic theoretical

framework for understanding evolution. He saw evolution as comprising

four laws:

- "Life by its own force, tends to increase the volume of all organs which possess the force of life, and the force of life extends the dimensions of those parts up to a extent that those parts bring to themselves;"

- "The production of a new organ in an animal body, results from a new requirement arising. and which continues to make itself felt, and a new movement which that requirement gives birth to, and its upkeep/maintenance;"

- "The development of the organs, and their ability, are constantly a result of the use of those organs."

- "All that has been acquired, traced, or changed, in the physiology of individuals, during their life, is conserved through the genesis, reproduction, and transmitted to new individuals who are related to those who have undergone those changes."

Lamarck's discussion of heredity

In

1830, in an aside from his evolutionary framework, Lamarck briefly

mentioned two traditional ideas in his discussion of heredity, in his

day considered to be generally true. The first was the idea of use

versus disuse; he theorized that individuals lose characteristics they

do not require, or use, and develop characteristics that are useful. The

second was to argue that the acquired traits were heritable. He gave as

an imagined illustration the idea that when giraffes

stretch their necks to reach leaves high in trees, they would

strengthen and gradually lengthen their necks. These giraffes would then

have offspring with slightly longer necks. In the same way, he argued, a

blacksmith,

through his work, strengthens the muscles in his arms, and thus his

sons would have similar muscular development when they mature. Lamarck

stated the following two laws:

- Première Loi: Dans tout animal qui n' a point dépassé le terme de ses développemens, l' emploi plus fréquent et soutenu d' un organe quelconque, fortifie peu à peu cet organe, le développe, l' agrandit, et lui donne une puissance proportionnée à la durée de cet emploi ; tandis que le défaut constant d' usage de tel organe, l'affoiblit insensiblement, le détériore, diminue progressivement ses facultés, et finit par le faire disparoître.

- Deuxième Loi: Tout ce que la nature a fait acquérir ou perdre aux individus par l' influence des circonstances où leur race se trouve depuis long-temps exposée, et, par conséquent, par l' influence de l' emploi prédominant de tel organe, ou par celle d' un défaut constant d' usage de telle partie ; elle le conserve par la génération aux nouveaux individus qui en proviennent, pourvu que les changemens acquis soient communs aux deux sexes, ou à ceux qui ont produit ces nouveaux individus.

English translation:

- First Law [Use and Disuse]: In every animal which has not passed the limit of its development, a more frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ, and gives it a power proportional to the length of time it has been so used; while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly weakens and deteriorates it, and progressively diminishes its functional capacity, until it finally disappears.

- Second Law [Soft Inheritance]: All the acquisitions or losses wrought by nature on individuals, through the influence of the environment in which their race has long been placed, and hence through the influence of the predominant use or permanent disuse of any organ; all these are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise, provided that the acquired modifications are common to both sexes, or at least to the individuals which produce the young.

In essence, a change in the environment brings about change in "needs" (besoins),

resulting in change in behavior, bringing change in organ usage and

development, bringing change in form over time—and thus the gradual transmutation of the species. However, as the evolutionary biologists and historians of science Michael Ghiselin and Steven Jay Gould have pointed out, these ideas were not original to Lamarck.

Weismann's experiment

August Weismann's germ plasm theory. The hereditary material, the germ plasm, is confined to the gonads and the gametes. Somatic cells (of the body) develop afresh in each generation from the germ plasm, creating an invisible "Weismann barrier" to Lamarckian influence from the soma to the next generation.

The idea that germline cells contain information that passes to each

generation unaffected by experience and independent of the somatic

(body) cells, came to be referred to as the Weismann barrier, as it would make Lamarckian inheritance from changes to the body difficult or impossible.

August Weismann conducted the experiment of removing the tails of 68 white mice,

and those of their offspring over five generations, and reporting that

no mice were born in consequence without a tail or even with a shorter

tail. In 1889, he stated that "901 young were produced by five

generations of artificially mutilated parents, and yet there was not a

single example of a rudimentary tail or of any other abnormality in this

organ." The experiment, and the theory behind it, were thought at the time to be a refutation of Lamarckism.

However, the experiment's effectiveness in refuting Lamarck's hypothesis is doubtful, as it did not address the use and disuse of characteristics in response to the environment. The biologist Peter Gauthier noted in 1990 that:

Can Weismann's experiment be considered a case of disuse? Lamarck proposed that when an organ was not used, it slowly, and very gradually atrophied. In time, over the course of many generations, it would gradually disappear as it was inherited in its modified form in each successive generation. Cutting the tails off mice does not seem to meet the qualifications of disuse, but rather falls in a category of accidental misuse... Lamarck's hypothesis has never been proven experimentally and there is no known mechanism to support the idea that somatic change, however acquired, can in some way induce a change in the germplasm. On the other hand it is difficult to disprove Lamarck's idea experimentally, and it seems that Weismann's experiment fails to provide the evidence to deny the Lamarckian hypothesis, since it lacks a key factor, namely the willful exertion of the animal in overcoming environmental obstacles.

The biologist and historian of science Michael Ghiselin also considered the Weismann tail-chopping experiment to have no bearing on the Lamarckian hypothesis, writing in 1994 that:

The acquired characteristics that figured in Lamarck's thinking were changes that resulted from an individual's own drives and actions, not from the actions of external agents. Lamarck was not concerned with wounds, injuries or mutilations, and nothing that Lamarck had set forth was tested or "disproven" by the Weismann tail-chopping experiment.

Textbook Lamarckism

The long neck of the giraffe

is often used as an example in popular explanations of Lamarckism.

However, this was only a small part of his theory of evolution towards

"perfection"; it was a hypothetical illustration; and he used it to

discuss his theory of heredity, not evolution.

The identification of Lamarckism with the inheritance of acquired

characteristics is regarded by evolutionary biologists including Michael

Ghiselin as a falsified artifact of the subsequent history of

evolutionary thought, repeated in textbooks without analysis, and

wrongly contrasted with a falsified picture of Darwin's thinking.

Ghiselin notes that "Darwin accepted the inheritance of acquired

characteristics, just as Lamarck did, and Darwin even thought that there

was some experimental evidence to support it." American paleontologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould

wrote that in the late 19th century, evolutionists "re-read Lamarck,

cast aside the guts of it ... and elevated one aspect of the

mechanics—inheritance of acquired characters—to a central focus it never

had for Lamarck himself."

He argued that "the restriction of 'Lamarckism' to this relatively

small and non-distinctive corner of Lamarck's thought must be labelled

as more than a misnomer, and truly a discredit to the memory of a man

and his much more comprehensive system."

Neo-Lamarckism

Context

The period of the history of evolutionary thought between Darwin's death in the 1880s, and the foundation of population genetics in the 1920s and the beginnings of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s, is called the eclipse of Darwinism

by some historians of science. During that time many scientists and

philosophers accepted the reality of evolution but doubted whether

natural selection was the main evolutionary mechanism.

Among the most popular alternatives were theories involving the

inheritance of characteristics acquired during an organism's lifetime.

Scientists who felt that such Lamarckian mechanisms were the key to

evolution were called neo-Lamarckians. They included the British botanist George Henslow

(1835–1925), who studied the effects of environmental stress on the

growth of plants, in the belief that such environmentally-induced

variation might explain much of plant evolution, and the American entomologist Alpheus Spring Packard, Jr., who studied blind animals living in caves and wrote a book in 1901 about Lamarck and his work. Also included were paleontologists like Edward Drinker Cope and Alpheus Hyatt,

who observed that the fossil record showed orderly, almost linear,

patterns of development that they felt were better explained by

Lamarckian mechanisms than by natural selection. Some people, including

Cope and the Darwin critic Samuel Butler,

felt that inheritance of acquired characteristics would let organisms

shape their own evolution, since organisms that acquired new habits

would change the use patterns of their organs, which would kick-start

Lamarckian evolution. They considered this philosophically superior to

Darwin's mechanism of random variation acted on by selective pressures.

Lamarckism also appealed to those, like the philosopher Herbert Spencer and the German anatomist Ernst Haeckel, who saw evolution as an inherently progressive process. The German zoologist Theodor Eimer combined Larmarckism with ideas about orthogenesis, the idea that evolution is directed towards a goal.

With the development of the modern synthesis

of the theory of evolution, and a lack of evidence for a mechanism for

acquiring and passing on new characteristics, or even their

heritability, Lamarckism largely fell from favour. Unlike neo-Darwinism,

neo-Lamarckism is a loose grouping of largely heterodox theories and

mechanisms that emerged after Lamarck's time, rather than a coherent

body of theoretical work.

19th century

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard tried to demonstrate Lamarckism by mutilating guinea pigs.

Neo-Lamarckian versions of evolution were widespread in the late 19th

century. The idea that living things could to some degree choose the

characteristics that would be inherited allowed them to be in charge of

their own destiny as opposed to the Darwinian view, which placed them at

the mercy of the environment. Such ideas were more popular than natural

selection in the late 19th century as it made it possible for

biological evolution to fit into a framework of a divine or naturally

willed plan, thus the neo-Lamarckian view of evolution was often

advocated by proponents of orthogenesis. According to the historian of science Peter J. Bowler, writing in 2003:

One of the most emotionally compelling arguments used by the neo-Lamarckians of the late nineteenth century was the claim that Darwinism was a mechanistic theory which reduced living things to puppets driven by heredity. The selection theory made life into a game of Russian roulette, where life or death was predetermined by the genes one inherited. The individual could do nothing to mitigate bad heredity. Lamarckism, in contrast, allowed the individual to choose a new habit when faced with an environmental challenge and shape the whole future course of evolution.

Scientists from the 1860s onwards conducted numerous experiments

that purported to show Lamarckian inheritance. Some examples are

described in the table.

| Scientist | Date | Experiment | Claimed result | Rebuttal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard | 1869 to 1891 | Cut sciatic nerve and dorsal spinal cord of guinea pigs, causing abnormal nervous condition resembling epilepsy | Epileptic offspring | Not Lamarckism, as no use and disuse in response to environment; results could not be replicated; cause possibly a transmitted disease. |

| Gaston Bonnier | 1884, 1886 | Transplant plants at different altitudes in Alps, Pyrenees | Acquired adaptations | Not controlled from weeds; likely cause genetic contamination |

| Joseph Thomas Cunningham | 1891, 1893, 1895 | Shine light on underside of flatfish | Inherited production of pigment | Disputed cause |

| Max Standfuss | 1892 to 1917 | Raise butterflies at low temperature | Variations in offspring even without low temperature | Richard Goldschmidt agreed; Ernst Mayr "difficult to interpret". |

Early 20th century

Paul Kammerer claimed in the 1920s to have found evidence for Lamarckian inheritance in midwife toads, in a case celebrated by the journalist Arthur Koestler, but the results are thought to be either fraudulent or at best misinterpreted.

A century after Lamarck, scientists and philosophers continued to

seek mechanisms and evidence for the inheritance of acquired

characteristics. Experiments were sometimes reported as successful, but

from the beginning these were either criticised on scientific grounds or

shown to be fakes. For instance, in 1906, the philosopher Eugenio Rignano argued for a version that he called "centro-epigenesis", but it was rejected by most scientists. Some of the experimental approaches are described in the table.

| Scientist | Date | Experiment | Claimed result | Rebuttal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Lawrence Tower | 1907 to 1910 | Colorado potato beetles in extreme humidity, temperature | Heritable changes in size, colour | Criticised by William Bateson; Tower claimed all results lost in fire; William E. Castle visited laboratory, found fire suspicious, doubted claim that steam leak had killed all beetles, concluded faked data. |

| Gustav Tornier | 1907 to 1918 | Goldfish, embryos of frogs, newts | Abnormalities inherited | Disputed; possibly an osmotic effect |

| Charles Rupert Stockard | 1910 | Repeated alcohol intoxication of pregnant guinea pigs | Inherited malformations | Raymond Pearl unable to reproduce findings in chickens; Darwinian explanation |

| Francis Bertody Sumner | 1921 | Reared mice at different temperatures, humidities | Inherited longer bodies, tails, hind feet | Inconsistent results |

| Michael F. Guyer, Elizabeth A. Smith | 1918 to 1924 | Injected fowl serum antibodies for rabbit lens-protein into pregnant rabbits | Eye defects inherited for 8 generations | Disputed, results not replicated |

| Paul Kammerer | 1920s | Midwife toad | Black foot-pads inherited | Fraud, ink injected; or, results misinterpreted; case celebrated by Arthur Koestler arguing that opposition was political |

| William McDougall | 1920s | Rats solving mazes | Offspring learnt mazes quicker (20 vs 165 trials) | Poor experimental controls |

| John William Heslop-Harrison | 1920s | Peppered moths exposed to soot | Inherited mutations caused by soot | Failure to replicate results; implausible mutation rate |

| Ivan Pavlov | 1926 | Conditioned reflex in mice to food and bell | Offspring easier to condition | Pavlov retracted claim; results not replicable |

| Coleman Griffith, John Detlefson | 1920 to 1925 | Reared rats on rotating table for 3 months | Inherited balance disorder | Results not replicable; likely cause ear infection |

| Victor Jollos | 1930s | Heat treatment in Drosophila melanogaster | Directed mutagenesis, a form of orthogenesis | Results not replicable |

Late 20th century

The British anthropologist Frederic Wood Jones and the South African paleontologist Robert Broom supported a neo-Lamarckian view of human evolution. The German anthropologist Hermann Klaatsch relied on a neo-Lamarckian model of evolution to try and explain the origin of bipedalism.

Neo-Lamarckism remained influential in biology until the 1940s when the

role of natural selection was reasserted in evolution as part of the

modern evolutionary synthesis.

Herbert Graham Cannon, a British zoologist, defended Lamarckism in his 1959 book Lamarck and Modern Genetics. In the 1960s, "biochemical Lamarckism" was advocated by the embryologist Paul Wintrebert.

Neo-Lamarckism was dominant in French biology for more than a century. French scientists who supported neo-Lamarckism included Edmond Perrier (1844–1921), Alfred Giard (1846–1908), Gaston Bonnier (1853–1922) and Pierre-Paul Grassé (1895–1985). They followed two traditions, one mechanistic, one vitalistic after Henri Bergson's philosophy of evolution.

In 1987, Ryuichi Matsuda coined the term "pan-environmentalism" for his evolutionary theory which he saw as a fusion of Darwinism with neo-Lamarckism. He held that heterochrony is a main mechanism for evolutionary change and that novelty in evolution can be generated by genetic assimilation. His views were criticized by Arthur M. Shapiro

for providing no solid evidence for his theory. Shapiro noted that

"Matsuda himself accepts too much at face value and is prone to

wish-fulfilling interpretation."

Ideological neo-Lamarckism

Trofim Lysenko promoted an ideological form of neo-Lamarckism which adversely influenced Soviet agricultural policy in the 1930s.

A form of Lamarckism was revived in the Soviet Union of the 1930s when Trofim Lysenko promoted the ideologically-driven research programme, Lysenkoism; this suited the ideological opposition of Joseph Stalin to genetics. Lysenkoism influenced Soviet agricultural policy which in turn was later blamed for crop failures.

Critique

George Gaylord Simpson in his book Tempo and Mode in Evolution (1944) claimed that experiments in heredity have failed to corroborate any Lamarckian process.

Simpson noted that neo-Lamarckism "stresses a factor that Lamarck

rejected: inheritance of direct effects of the environment" and

neo-Lamarckism is closer to Darwin's pangenesis than Lamarck's views.

Simpson wrote, "the inheritance of acquired characters, failed to meet

the tests of observation and has been almost universally discarded by

biologists."

Botanist Conway Zirkle pointed out that Lamarck did not originate the hypothesis that acquired characteristics could be inherited, so it is incorrect to refer to it as Lamarckism:

What Lamarck really did was to accept the hypothesis that acquired characters were heritable, a notion which had been held almost universally for well over two thousand years and which his contemporaries accepted as a matter of course, and to assume that the results of such inheritance were cumulative from generation to generation, thus producing, in time, new species. His individual contribution to biological theory consisted in his application to the problem of the origin of species of the view that acquired characters were inherited and in showing that evolution could be inferred logically from the accepted biological hypotheses. He would doubtless have been greatly astonished to learn that a belief in the inheritance of acquired characters is now labeled "Lamarckian," although he would almost certainly have felt flattered if evolution itself had been so designated.

Peter Medawar

wrote regarding Lamarckism, "very few professional biologists believe

that anything of the kind occurs—or can occur—but the notion persists

for a variety of nonscientific reasons." Medawar stated there is no

known mechanism by which an adaptation acquired in an individual's

lifetime can be imprinted on the genome and Lamarckian inheritance is

not valid unless it excludes the possibility of natural selection but

this has not been demonstrated in any experiment.

Martin Gardner wrote in his book Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957):

A host of experiments have been designed to test Lamarckianism. All that have been verified have proved negative. On the other hand, tens of thousands of experiments— reported in the journals and carefully checked and rechecked by geneticists throughout the world— have established the correctness of the gene-mutation theory beyond all reasonable doubt... In spite of the rapidly increasing evidence for natural selection, Lamarck has never ceased to have loyal followers.... There is indeed a strong emotional appeal in the thought that every little effort an animal puts forth is somehow transmitted to his progeny.

According to Ernst Mayr, any Lamarckian theory involving the inheritance of acquired characters has been refuted as "DNA

does not directly participate in the making of the phenotype and that

the phenotype, in turn, does not control the composition of the DNA."

Peter J. Bowler has written that although many early scientists took

Lamarckism seriously, it was discredited by genetics in the early

twentieth century.

Mechanisms resembling Lamarckism

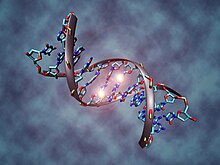

Studies in the field of epigenetics, genetics and somatic hypermutation have highlighted the possible inheritance of traits acquired by the previous generation. However, the characterization of these findings as Lamarckism has been disputed.

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

DNA molecule with epigenetic marks, created by methylation, enabling a neo-Lamarckian pattern of inheritance for some generations.

Epigenetic inheritance has been argued by scientists including Eva Jablonka and Marion J. Lamb to be Lamarckian. Epigenetics is based on hereditary elements other than genes that pass into the germ cells. These include methylation patterns in DNA and chromatin marks on histone proteins, both involved in gene regulation. These marks are responsive to environmental stimuli, differentially affect gene expression, and are adaptive, with phenotypic

effects that persist for some generations. The mechanism may also

enable the inheritance of behavioral traits, for example in chickens rats

and human populations that have experienced starvation, DNA methylation

resulting in altered gene function in both the starved population and

their offspring. Methylation similarly mediates epigenetic inheritance in plants such as rice. Small RNA molecules, too, may mediate inherited resistance to infection. Handel and Romagopalan commented that "epigenetics allows the peaceful co-existence of Darwinian and Lamarckian evolution."

Joseph Springer and Dennis Holley commented in 2013 that:

Lamarck and his ideas were ridiculed and discredited. In a strange twist of fate, Lamarck may have the last laugh. Epigenetics, an emerging field of genetics, has shown that Lamarck may have been at least partially correct all along. It seems that reversible and heritable changes can occur without a change in DNA sequence (genotype) and that such changes may be induced spontaneously or in response to environmental factors—Lamarck's "acquired traits." Determining which observed phenotypes are genetically inherited and which are environmentally induced remains an important and ongoing part of the study of genetics, developmental biology, and medicine.

The prokaryotic CRISPR system and Piwi-interacting RNA could be classified as Lamarckian, within a Darwinian framework.

However, the significance of epigenetics in evolution is uncertain. Critics such as the evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne point out that epigenetic inheritance lasts for only a few generations, so it is not a stable basis for evolutionary change.

The evolutionary biologist T. Ryan Gregory

contends that epigenetic inheritance should not be considered

Lamarckian. According to Gregory, Lamarck did not claim that the

environment directly affected living things. Instead, Lamarck "argued

that the environment created needs to which organisms responded by using

some features more and others less, that this resulted in those

features being accentuated or attenuated, and that this difference was

then inherited by offspring." Gregory has stated that Lamarckian

evolution in epigenetics is more like Darwin's point of view than

Lamarck's.

In 2007, David Haig

wrote that research into epigenetic processes does allow a Lamarckian

element in evolution but the processes do not challenge the main tenets

of the modern evolutionary synthesis as modern Lamarckians have claimed.

Haig argued for the primacy of DNA and evolution of epigenetic switches

by natural selection.

Haig has written that there is a "visceral attraction" to Lamarckian

evolution from the public and some scientists, as it posits the world

with a meaning, in which organisms can shape their own evolutionary

destiny.

Thomas Dickens and Qazi Rahman (2012) have argued that epigenetic

mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification are

genetically inherited under the control of natural selection and do not

challenge the modern synthesis. They dispute the claims of Jablonka and

Lamb on Lamarckian epigenetic processes.

Edward J. Steele's disputed Neo-Lamarckian mechanism involves somatic hypermutation and reverse transcription by a retrovirus to breach the Weismann barrier to germline DNA.

In 2015, Khursheed Iqbal and colleagues discovered that although

"endocrine disruptors exert direct epigenetic effects in the exposed

fetal germ cells, these are corrected by reprogramming events in the

next generation."

Also in 2015, Adam Weiss argued that bringing back Lamarck in the

context of epigenetics is misleading, commenting, "We should remember

[Lamarck] for the good he contributed to science, not for things that

resemble his theory only superficially. Indeed, thinking of CRISPR and

other phenomena as Lamarckian only obscures the simple and elegant way

evolution really works."

Somatic hypermutation and reverse transcription to germline

In the 1970s, the Australian immunologist Edward J. Steele developed a neo-Lamarckian theory of somatic hypermutation within the immune system and coupled it to the reverse transcription of RNA derived from body cells to the DNA of germline

cells. This reverse transcription process supposedly enabled

characteristics or bodily changes acquired during a lifetime to be

written back into the DNA and passed on to subsequent generations.

The mechanism was meant to explain why homologous DNA sequences from the VDJ gene

regions of parent mice were found in their germ cells and seemed to

persist in the offspring for a few generations. The mechanism involved

the somatic selection and clonal amplification of newly acquired antibody gene sequences generated via somatic hypermutation in B-cells. The messenger RNA products of these somatically novel genes were captured by retroviruses endogenous

to the B-cells and were then transported through the bloodstream where

they could breach the Weismann or soma-germ barrier and reverse

transcribe the newly acquired genes into the cells of the germ line, in

the manner of Darwin's pangenes.

Neo-Lamarckian inheritance of hologenome

The historian of biology Peter J. Bowler

noted in 1989 that other scientists had been unable to reproduce his

results, and described the scientific consensus at the time:

There is no feedback of information from the proteins to the DNA, and hence no route by which characteristics acquired in the body can be passed on through the genes. The work of Ted Steele (1979) provoked a flurry of interest in the possibility that there might, after all, be ways in which this reverse flow of information could take place. ... [His] mechanism did not, in fact, violate the principles of molecular biology, but most biologists were suspicious of Steele's claims, and attempts to reproduce his results have failed.

Bowler commented that "[Steele's] work was bitterly criticized at the

time by biologists who doubted his experimental results and rejected

his hypothetical mechanism as implausible."

Hologenome theory of evolution

The hologenome theory of evolution, while Darwinian, has Lamarckian aspects. An individual animal or plant lives in symbiosis with many microorganisms, and together they have a "hologenome" consisting of all their genomes. The hologenome can vary like any other genome by mutation, sexual recombination, and chromosome rearrangement,

but in addition it can vary when populations of microorganisms increase

or decrease (resembling Lamarckian use and disuse), and when it gains

new kinds of microorganism (resembling Lamarckian inheritance of

acquired characteristics). These changes are then passed on to

offspring.

The mechanism is largely uncontroversial, and natural selection does

sometimes occur at whole system (hologenome) level, but it is not clear

that this is always the case.

Lamarckian use and disuse compared to Darwinian evolution, the Baldwin effect, and Waddington's genetic assimilation. All the theories offer explanations of how organisms respond to a changed environment with adaptive inherited change.

Baldwin effect

The Baldwin effect, named after the psychologist James Mark Baldwin

by George Gaylord Simpson in 1953, proposes that the ability to learn

new behaviours can improve an animal's reproductive success, and hence

the course of natural selection on its genetic makeup. Simpson stated

that the mechanism was "not inconsistent with the modern synthesis" of

evolutionary theory,

though he doubted that it occurred very often, or could be proven to

occur. He noted that the Baldwin effect provide a reconciliation between

the neo-Darwinian and neo-Lamarckian approaches, something that the

modern synthesis had seemed to render unnecessary. In particular, the

effect allows animals to adapt to a new stress in the environment

through behavioural changes, followed by genetic change. This somewhat

resembles Lamarckism but without requiring animals to inherit

characteristics acquired by their parents. The Baldwin effect is broadly accepted by Darwinists.

In sociocultural evolution

Within the history of technology,

Lamarckism has been used in linking cultural development to human

evolution by classifying artefacts as extensions of human anatomy: in

other words, as the acquired cultural characteristics of human beings.

Ben Cullen has shown that a strong element of Lamarckism exists in sociocultural evolution.

Lamarckism was influential in some non -Western nations like China, for

it even became a part of the Chinese translation of the Origin of

Species.