From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tax resistance in the United States has been practiced at least since colonial times, and has played important parts in American history.

The

theory that there should be "no taxation without representation," while

it did not originate in America, is often associated with the

American Revolution, in which that slogan did strong duty. It continues to be a rallying cry for tax rebellions today. American

Henry David Thoreau's theory of

civil disobedience

has proven to be extremely influential, and its influence today is not

limited to tax resistance stands and campaigns but to all manner of

refusal to obey unjust laws. These are among the theories of tax

resistance that have taken on a particularly American flavor and have

animated and inspired American tax resisters and tax resistance

campaigns.

No taxation without representation

In English political philosophy of the late 18th century, the theory

was prominent that in order for the sovereign to exact a tax on a

population, that population must be represented in a legislature that

had the sole power to levy the tax. That theory was made axiomatic in

the form of the slogan "no taxation without representation" (and similar

expressions).

The American colonies did not have representatives in the British

parliament, and so this axiom became a useful platform for colonial

rebels to justify their rebellion against direct taxes imposed by the

crown.

The standard-issue District of Columbia license plate bears the phrase, "Taxation Without Representation".

The "no taxation without representation" slogan was brought to bear in the arguments for tax resistance by African-Americans and by American women

who did not have the right to vote or serve in the legislature. It is

used today by the District of Columbia as part of a complaint that

residents of the district have no (voting) Congressional

representatives.

The phrase has such potent currency in American thought that it

is frequently used today in the context of tax debates that have little

to do with legislative representation, at least in the way that the

original coiners of the phrase would have understood: For example,

complaints that Congressional representatives only represent certain special interests, or that the complainer doesn't feel that his or her point of view is represented in legislative debates or actions.

Civil disobedience

Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay

On Resistance to Civil Government — now usually referred to as

Civil Disobedience — is part of the canon of American political philosophy.

It was prompted by Thoreau's refusal to pay a poll tax because of

unwillingness to support a government that was enforcing the slavery of

Americans and what he felt was an unjust war against Mexico.

Thoreau argued that obedience to government is often misplaced,

and that people should develop and trust their own consciences rather

than use the law as a crutch.

Thoreau's philosophy has inspired many tax resisters since,

especially those who have acted individually (not as part of a tax

strike or other large-scale movement) and from motives of conscientious

objection.

Conscientious objection to military taxation

The theory that taxpayers become complicit in the actions of their

government when they pay for the government's functioning and

requisitions through their taxes, and that therefore one must scrutinize

the actions of the government and refuse to pay for them if they become

grossly immoral, is key to the war tax resistance practiced by American

Quakers since colonial times.

It also forms an important philosophical basis for other religious and

secular American war tax resisters down to the present day.

War tax resisters in the United States pioneered the idea that

conscientious objection to military taxation

ought to be a legally protected right: that is, taxpayers who are

morally opposed to taking part in war should not be forced to fund war,

just as governments often permit such people to avoid military

conscription.

This theory has been extended by people who oppose other aspects

of government funding. A few have refused to pay taxes on the grounds

that some government health spending goes to institutions that provide

abortions. A number of Amish people refused to pay taxes for government social insurance programs on conscientious grounds.

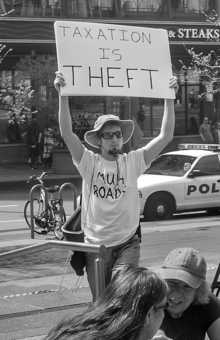

Taxation as theft

A demonstrator at a "Tax Day" demonstration in Cincinnati, Ohio, holds a sign reading "taxation is theft"

The theory that taxation is ethically indistinguishable from robbery is a

staple of American anarchist and (often) libertarian thought. American

anarchist philosopher

Lysander Spooner put it this way:

Taxation

without consent is as plainly robbery, when enforced against one man,

as when enforced against millions… Taking a man's money without his

consent, is also as much robbery, when it is done by millions of men,

acting in concert, and calling themselves a government, as when it is

done by a single individual, acting on his own responsibility, and

calling himself a highwayman. Neither the numbers engaged in the act,

nor the different characters they assume as a cover for the act, alter

the nature of the act itself.

The original U.S.

Libertarian Party platform (1972) agreed that taxation was always a violation of the rights of the individual:

- Since we believe that every man is entitled to keep the fruits

of his labor, we are opposed to all government activity which consists

of the forcible collection of money or goods from citizens in violation

of their individual rights. Specifically, we support the eventual repeal

of all taxation. We support a system of voluntary fees for services

rendered as a method for financing government in a free society.

Tax protester theories

An enduring mythology of

tax protester arguments

asserts that the tax system operating in the United States is

unconstitutional, illegal, or doesn't actually apply to most of the

people currently being subjected to it.

These arguments, though they often take the form of "totally discredited legal positions and/or meritless factual positions,"

are often persuasive to people who have an unsophisticated

understanding of the legal system and who are susceptible to look

uncritically on arguments that appeal to their financial self-interest.

For example, in the early 1980s, an epidemic of tax protest swept

General Motors plants in Flint, Michigan, as thousands of employees

there told

GM to stop withholding

income tax from their salaries after they attended seminars or listened

to lectures on tape from the tax protester group “We The People ACT.”

Practice

The

following sections briefly describe some of the more prominent examples

of tax resistance in colonial America and the United States:

Quaker conscientious objection to military taxation

The

Society of Friends

(Quakers) had a tradition of refusing to pay tithes to the

establishment church, and of refusing to pay explicit war taxes, from

the early years of the establishment of the sect.

When Quakers were permitted to establish an American colony,

Pennsylvania,

that they could run to some extent on their religious principles, the

Pennsylvania Assembly often offered some resistance to attempts by the

crown to exact money from the colony for the purposes of military

defense.

During the

French and Indian war,

the Pennsylvania colonial assembly conceded, and began raising a tax

from Pennsylvania residents for military fortifications. This led to

some, including influential Quakers

John Woolman and

Anthony Benezet, refusing to pay such taxes for reasons of conscientious objection.

This stand, and the eloquence the resisters employed to explain

it, proved influential, and a Quaker tradition of war tax resistance has

waxed and waned through American history to the present day.

Colonial resistance

A

typical American colonial government was headed by a governor, who was

appointed by the Crown and meant to represent the interests of the home

country, and a colonial assembly, elected by the colonists themselves.

The two not infrequently came into conflict over issues of taxation, and

when the governor assumed the right to tax colonists without the

consent of their legislature, this conflict might result in tax

resistance.

This happened for example in 1687 when New England governor

Edmund Andros

attempted to assess a new tax. Colonists declared their unwillingness

to pay such a tax, were imprisoned on orders of the governor, and this

ultimately led to the

1689 Boston revolt

in which Andros was overthrown. This muscle-flexing by American

colonists was an important precursor of the American Revolution, such

that

Ipswich, where a declaration defying the tax was signed, bills itself as "The Birthplace of American Independence 1687".

The

War of the Regulation

in colonial North Carolina was another important precursor of the

American Revolution. Colonists, fed up with what they viewed as a

corrupt and unrepresentative colonial government, stopped paying taxes

and ultimately rose in an armed revolt. In this case it was the entire

government — the governor, the assembly, and the corrupt bureaucracy —

that was the target of the rebellion.

Independence-minded colonials used a variety of tactics to

increase the economic independence and self-reliance of the colonies

while denying economic resources to the Crown. This included rampant

smuggling and attacks on British customs ships (as in the

Gaspee Affair), the refusal to allow British monopoly products to be brought to market (as in the

Boston Tea Party and

Philadelphia Tea Party),

boycotts of British-manufactured goods and the encouragement of local

production of replacement goods, and sanctions ranging from social

boycott to violent attacks aimed at tax collectors and collaborators.

The success of measures like these led John Adams to assert that the

American Revolution had already been accomplished before the

Revolutionary War began — that the war was less a revolution than a

failed counterrevolution.

Resistance in the post-revolutionary period

After

the success of the American Revolution, the independent United States

government of the former colonies was confronted by its own tax

resistance campaigns. Three were suppressed militarily by the fledgling

United States government:

Shays' Rebellion

Massachusetts farmers were motivated in part by increased taxes and heavy-handed tax enforcement when they rose up in

Shays' Rebellion.

They took action against government agencies that were enforcing tax

seizures, preventing their operation, until the suppression of the

rebellion.

The Whiskey Rebellion

Farmers far from coastal ports and population centers would often

ferment and distill their grain into whiskey locally because it was more

economic to bring whiskey to market than grain, from the point of view

of transportation costs.

Thus, when United States government put an excise tax on whiskey, this

was seen as an imposition by coastal elites at the expense of rural

farmers and was widely resented and resisted.

While resistance in the form of refusal to pay the excise tax or

to cooperate in the enforcement of excise laws persisted and largely

succeeded in some areas, in Western Pennsylvania this resistance erupted into attacks on tax collectors and eventual armed revolt — the

Whiskey Rebellion — which was violently suppressed by federal government troops under the command of former revolutionary war commander in chief

George Washington.

Fries's Rebellion

Fries's Rebellion began in opposition to a federal window-tax

instituted by the Adams administration, with resisters impeding the tax

assessors and refusing to pay the assessed taxes. This resistance

movement, too, was successfully suppressed by the federal government

when it rose to the level of armed rebellion.

Native / immigrant conflicts

The

United States government is largely run by and on behalf of the

European immigrant community, while United States territory also

encompasses the land of native people, some of whom live in separate

sovereign or semi-sovereign nations. Conflicts periodically erupt over

who could tax whom.

In the late-19th century, such conflicts led to tax resistance,

for example from thousands of people of part-native ancestry in Dakota

territory who forced the tax collector to retreat without his prize, from Crow in Montana who refused to pay for several years until the government there confiscated their livestock, or from non-native residents of Oklahoma Territory who wanted to be free from Cherokee Nation taxes.

Such conflicts continued into the 20th century. For example

Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson led a tax resistance campaign of the

Tuscarora Nation

in 1959 in which they refused to pay state income tax, publicly

destroyed tax summonses, and engaged in sit-ins and other such protests. Members of the

Seneca Nation

blocked the Southern Tier Expressway in New York to protest the state's

attempt to extend a state sales tax to them in 1992. When members of

the

Iroquois Confederacy

blocked roads in a similar conflict in 1997, law enforcement responded

with brutal violence (the state would eventually pay out $2.7

million to victims).

African-Americans

Tax resistance has occasionally been deployed in the battle for civil rights for

black people in the United States. For example:

The "no taxation without representation" argument was evoked by African-American businessman

Paul Cuffee,

who refused to pay his state taxes and petitioned the legislature in

1780 and 1781 on behalf of himself and other African-Americans, saying

"we apprehend ourselves to be aggrieved, in that… we are not allowed the

privilege of freemen of the State, having no vote or influence in the

election of those that tax us."

Robert Purvis

refused to pay a school tax in Philadelphia in 1853, on the grounds

that his children were not allowed to attend the whites-only schools the

tax supported. "I object", he wrote, "to the payment of this tax, on

the ground that my rights as a citizen, and my feelings as a man and a

parent have been grossly outraged in depriving me, in violation of law

and justice, of the benefits of the school system which this tax was

designed to sustain."

Undermining Reconstruction state governments

After the

American Civil War, the United States government established

Reconstruction era governments in the states of the former

Confederacy that included

black and

carpetbagger representatives. The loss of political power by the formerly dominant

white supremacists

led to resentment, protest, and the formation of paramilitaries and

parallel governments. Occasionally, tax resistance was used as a tactic

to withdraw financial support and political legitimacy from the

reconstruction governments in favor of the white supremacist parallel

governments.

White supremacist gubernatorial candidate

John McEnery established a parallel government in Reconstruction Louisiana, in opposition to the carpetbagger government of governor

William Pitt Kellogg, and urged sympathetic citizens to pay taxes to his government rather than the Kellogg "usurpation."

Railroad bond shenanigans

In

the 1870s a number of American localities were victims of railroad bond

swindles. Promoters would ask the residents to vote to issue bonds to

pay for the running of a railroad line to their area, these bonds being

backed by the local tax base. In theory the economic growth that would

come from the new rail line would more than pay for the bonds by the

time they were mature and the bondholders needed to be paid off. In

fact, the railroad never materialized and the bond promoters vanished

with the money.

Some of these localities organized and refused to honor the bonds

they had issued. Because by the time the bonds had matured they had

likely been sold to new owners who did not participate in the original

fraud, the court system was not usually very sympathetic to the

defrauded taxpayers.

But this led to some notable examples of organized tax resistance in the United States.

For instance, in Cass and

St. Clair

counties, Missouri, local judges were elected who refused to enforce

higher court rulings in favor of the bondholders that would have forced

the County to inflict a tax in order to pay off the bonds. For a time,

the judges held court in a cave in order to evade their eventual

jailings for contempt of court.

In Steuben County, New York, the bondholders succeeded in forcing

the community to create a property tax to pay off the bonds, but

property owners refused to pay the tax and rallied to the support of

those whose property was seized for failure to pay, successfully

disrupting tax auctions.

In Kentucky, refusal to assess or pay taxes to pay off the bond

swindle persisted for decades. Some towns refused to elect sheriffs or

public officials of any kind (or no candidates could be found for the

positions) so that nobody was legally qualified to assess taxes or

engage in property seizures for failure to pay taxes. Local judges went

into hiding to evade the rulings of higher courts. Armed citizens

intimidated outsiders who tried to come and collect taxes by force.

Women's suffrage

Tax

resistance was a less important part of the women's suffrage struggle

in the United States than it was in the United Kingdom, but it still

played a role and had some notable practitioners.

- Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of those States, in

which woman has now by law a right to the property she inherits, to

refuse to pay taxes. She is unrepresented in the Government…

Lucy Stone

refused to pay her tax in 1858, on the grounds "that women suffer

taxation, and yet have no representation, which is not only unjust to

one-half the adult population, but is contrary to our theory of

government."

Abby and

Julia Smith

were landowners in Glastonbury, Connecticut, who found in the 1870s

that their property tax assessments kept rising relative to those of the

male property owners of the area who could vote in local elections.

They responded by refusing to pay taxes on "no taxation without

representation" grounds, and their battle soon became a

cause célèbre among suffrage activists and sympathizers throughout the country (in part thanks to the sisters' knack for publicity).

Anna Howard Shaw's automobile was sold at tax auction in 1915 in a celebrated tax resistance case.

"Dr. Shaw has always believed in the contention of the Colonies that

'taxation without representation is tyranny' and has consistently

protested along this line when paying her taxes," she explained.

Tax resistance by newly-enfranchised women in Pennsylvania

As

women won the right to vote in the United States, they sometimes also

became vulnerable to taxes that had previously only applied to men. When

this happened in Pennsylvania, the shock was accompanied by resentment

that the school tax in question applied mostly to women living in rural

areas and not to those living in the largest Pennsylvania cities.

This example of American tax resistance is particularly

interesting because although it involved thousands of women in many

parts of the state and persisted for several years, there is little

evidence that the resistance was formally organized, and it wasn't

accompanied by much in the way of open protest — no rallies, picket

marches, petitions, manifestos, named organizations, political

coalitions, or things of that nature. It seems to have been a form of

leaderless resistance.

At first the women were emboldened by a quirk in the law that

forbade "the arrest or imprisonment for non-payment of any tax of any

female or infant or person found by inquisition to be of unsound mind." It took the state legislature a couple of years to update that law after the women's tax resistance began, and several women were eventually jailed, briefly, for their resistance.

"Bond Slackers" during World War Ⅰ

Although the

U.S. government raised some of its war budget via taxes, the most visible public war funding measure during World War

Ⅰ was the

Liberty Bond program. Citizens were encouraged to loan money to the government for its war effort through the purchase of bonds.

Although the purchase of bonds was ostensibly voluntary, strong coercive pressure — up to and including mob violence — was directed at those who would not buy.

"Bond slackers" (the popular term at the time for people who did not

buy war bonds, or did not buy them in sufficient quantity) could be run

out of town, might lose their jobs, have their property stolen or vandalized, might be tarred-and-feathered, otherwise tortured, coated in paint, threatened with murder,

or subjected to hours of questioning by hooded interrogators in

impromptu star chambers in the hopes of prompting them to say something

that would incriminate them under the

Espionage Act.

Those who resisted such pressure and refused to buy war bonds

included conscientious objectors to war such as Jehovah's Witnesses and members of traditional

peace churches such as

Mennonites, anti-capitalist radicals, and European immigrants from countries the

U.S. and its allies were fighting.

Herbert Lord,

Director of Finance for the War Department, considered this "an

organized effort to discourage and defeat the loan," and it was

attributed to a conspiracy of "pro-German agents."

Property tax strikes during the Great Depression

The

Great Depression

introduced unprecedented tax burdens to Americans. While real-estate

values plummeted and unemployment skyrocketed, the cost of government

remained high. As a result, taxes as a percentage of the national income

nearly doubled from 11.6 percent in 1929 to 21.1 in 1932. Most of the

increase took place at the local level and especially squeezed the

resources of real estate taxpayers. Local tax delinquency rose steadily

to a record of 26.3% in 1933.

Many Americans reacted to these conditions by forming taxpayers'

leagues to call for lower taxes and cuts in government spending. By some

estimates, there were three thousand of these leagues by 1933.

Taxpayers' leagues endorsed such measures as laws to limit and rollback

taxes, lowered penalties on tax delinquents, and cuts in government

spending. Partly as a result of their efforts, sixteen states and

numerous localities adopted property tax limitations while three states

instituted homestead exemptions.

While taxpayers' leagues usually favored traditional legal and

political strategies, a few promoted tax resistance. Probably the best

known of these was the

Association of Real Estate Taxpayers (

ARET) in

Chicago. From 1930 to 1933, it led one of the largest tax strikes in American history.

ARET

functioned primarily as a cooperative legal service. Each member paid

annual dues of $15 to fund lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of

real-estate assessments. The suits, when finally filed, took the form

of a 7,000-page, two-foot-thick book listing the names and tax data for

all 26,000 co-litigants.

The radical side of the movement became apparent by early 1931 when

ARET

called for taxpayers to withhold real-estate taxes (or "strike")

pending a final ruling by the Illinois Supreme Court, and later the U.S.

Supreme Court. Mayor

Anton Cermak

and other politicians desperately tried to break the strike by

threatening criminal prosecution, revocation of city services, and the

seizure of property.

The Association's influence peaked in late 1932, with a

membership of near 30,000 people, a budget of over $600,000, and its own

radio show. A failed legal suit, government counter-measures, and

infighting took their toll and the movement, having in large part

accomplished its goals, declined thereafter.

The emergence of a non-sectarian war tax resistance movement

Tax resistance motivated by conscientious objection to war had

traditionally been practiced in the United States under the Christian

theory of

nonresistance as extrapolated by the historic

peace churches,

and its development had largely taken place within the context of those

churches. Rare exceptions included the brief flowering of tax

resistance among the New England

Transcendentalists like

Henry David Thoreau,

a small war tax resistance contingent in the late-19th Century pacifist

movement, and a few war tax resisters in small sects like the

International Bible Students and

Rogerenes.

After World War

Ⅱ, a non-sectarian

war tax resistance movement began to come together, and would develop

its own practices of war tax resistance under a more secular theory of

pacifism.

In 1948, the group

Peacemakers formed to (loosely) organize this movement. This group would develop a pacifist theory of

conscientious objection to military taxation

that was not tied to a particular religious doctrine. They published a

guide to war tax resistance in 1963 and developed tactics of resistance

practice and of publicity that would lead to the growth of the movement,

to a new resurgence of war tax resistance among the traditional peace

churches, and to the establishment of nonsectarian war tax resistance as

an ongoing part of the American scene.

Foes of social security taxation

The United States

Social Security

program had its share of critics and faced political opposition. It

also evoked some tax resistance against the payroll and self-employment

taxes that funded it. This came from two factions in particular:

conservatives who opposed the government program for ideological

reasons, and

Amish who had religious prohibitions against participating in insurance programs in general.

Conservative opposition

American conservatives who refused to pay payroll or self-employment

taxes for the social security program expressed their opposition in

terms of opposing government overreach into private lives and contracts,

and opposition to socialism. "For those of us who still have confidence

in our own ability," one wrote, "such a socialistic thing should not be

forced upon us."

About a dozen women from around Marshall, Texas organized in 1951

to refuse to submit Social Security taxes on behalf of their domestic

help. "It's not the money, it's the principle," said spokesperson

Carolyn M. Abney. "That law is unconstitutional."

It is a violation of the sanctity

of the American home. The law violates a basic American freedom. Already

business has been socialized and the American home is the last

stronghold against socialism. This may sound dramatic, but we are

fighting to preserve the freedoms our forefathers gave to us.

— Carolyn M. Abney, in "Texas Housewives to Press Social Security Test Case". Reading Eagle. 1952-07-01.

The "Texas Housewives" (as they were invariably called in the newspapers) lost a court case in 1952. They appealed on

13th Amendment

grounds; that's the amendment that bans involuntary servitude — their

attorney explained that the law "forces these housewives to be unpaid

tax collectors for the government." They lost this case as well, and in 1954 they failed in an attempted Supreme Court appeal. Meanwhile the government seized the resisted money from their bank accounts.

The women continued to defy the

Internal Revenue Service (

I.R.S.)

for some time after, claiming that the courts had not answered the

Constitutional question but had only verified the tax statute. They eventually gave up the fight and began to pay the required quarterly taxes for their employees.

Mary Cain

refused to pay $42.87 in self-employment tax in 1952 and hid her assets

to make sure the government would have to make it a criminal matter

(and thus a possible test case) rather than a simple civil asset

seizure. In the case that eventually resulted, Cain's arguments were turned down by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and she had no luck with a Supreme Court appeal, but the government eventually dropped the case anyway.

When the government padlocked the office of her newspaper as part of a

seizure process, Cain sawed the lock off the door and mailed it to the

I.R.S. defiantly. "I’ve had enough of the New Deal. I’m sick of the whole Truman administration," she said.

Vivien Kellems,

who had previously tangled with the government by refusing to withhold

income taxes from her employees, refused to pay the self-employment tax

on her income in 1952, and recruited a small group of other

businesspersons (including Mary Cain) to join her protest. She wrote in a

letter to Treasury Secretary

John W. Snyder

that she felt she already had "adequate insurance" and she urged the

government to indict her so that she could be a test case to the Supreme

Court.

Conscientious objection from the Amish

The Amish have a strong tradition of

mutual aid and believe that purchasing insurance betrays distrust in God's providence

and in the community of believers. The original name of the Social

Security system was "Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance," and

Amish people interpreted it as a forbidden form of insurance.

Anyone who does not provide for

their relatives, and especially for their own household, has denied the

faith and is worse than an unbeliever.

Because of this, when the U.S. government extended the Social

Security system to cover farmers in 1955, many Amish refused to

participate, and the government responded by seizing their property.

After some farmers had bank accounts seized, others closed their

accounts. When the government tried to levy checks due to the resisters

from the milk processing cooperatives they sold their milk to, the

cooperatives (also in Amish hands) refused to hand over the checks.

The government was then reduced to seizing livestock. In a

celebrated case in 1961, the government seized Valentine Byler's horses

during Spring plowing. Asked about this insensitivity to Byler's

livelihood, the district

I.R.S.

Chief of Collections answered, "Plowing never occurred to me. I live in

an apartment." Byler received messages of support from around the

country, and the press took up his cause.

What kind of "welfare" is it that

takes a farmer’s horses away at spring plowing time in order to dragoon a

whole community into a "benefit" scheme it neither needs nor wants, and

which offends its deeply held religious scruples?

— "Welfarism Gone Mad". New York Herald Tribune. 1961-05-14.

The struggle would continue for a decade. Legislation that would

exempt the Amish from the Social Security program was introduced in

Congress at least as early as 1959,

and some of the resisters took the unusual step (unusual for the Amish)

of petitioning the government in 1961. In 1965, the United States

changed the Social Security law in a way that exempted self-employed

Amish people from having to pay into the Social Security program.

War tax resistance during the Vietnam War

In 1966,

A.J. Muste circulated a tax refusal pledge meant as an advertiement for the

Washington Post that 370 people signed, including the singer

Joan Baez, on the grounds "that the ordinary channels of protest have been exhausted."

This country has gone mad. But I

will not go mad with it. I will not pay for organized murder. I will not

pay for the war in Vietnam.

— Joan Baez

In 1967,

President Lyndon Johnson proposed an income tax

surtax explicitly to pay for war expenses.

This was the first tax in the modern United States that was explicitly a

"war tax" and helped to boost the prominence of war tax resistance as a

protest tactic.

In early 1967, a "No Tax for War Committee" organized by

Maurice McCrackin circulated a sign-on statement that eventually attracted more than 200 signatures, and that read:

Because so much of the tax paid the federal government goes for

poisoning of food crops, blasting of villages, napalming and killing

thousands upon thousands of people, as in Vietnam at the present time, I

am not going to pay taxes on 1966 income.

A "Writers & Editors War Tax Protest" the same year was somewhat

less bold in its declaration (not all declaring total resistance, but

some refusing to pay only the 10% surtax or only 23% of their total tax)

but more impressive in its list of names. The protest, which appeared

in

New York Post,

New York Times Book Review and

Ramparts was eventually signed by about 528 people including

Nelson Algren,

James Baldwin,

Robert Bly,

Noam Chomsky,

Robert Creeley,

David Dellinger,

Philip K. Dick,

Robert Duncan,

Lawrence Ferlinghetti,

Leslie Fiedler,

Betty Friedan,

Allen Ginsberg,

Todd Gitlin,

Paul Goodman,

Edward S. Herman,

Paul Krassner,

Staughton Lynd,

Dwight Macdonald,

Jackson Mac Low,

Norman Mailer,

Peter Matthiessen,

Milton Mayer,

Ed McClanahan,

Henry Miller,

Carl Oglesby,

Tillie Olsen,

Grace Paley,

Thomas Pynchon,

Adrienne Rich,

Kirkpatrick Sale,

Ed Sanders,

Robert Scheer,

Peter Dale Scott,

Susan Sontag,

Terry Southern,

Benjamin Spock,

Gloria Steinem,

William Styron,

Norman Thomas,

Hunter S. Thompson,

Lew Welch,

John Wieners,

Kurt Vonnegut and

Howard Zinn. The ad included a quotation from Thoreau's

Civil Disobedience that ends:

If a thousand men would not pay

their tax bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody

measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the state to commit

violence and shed innocent blood.

— Henry D. Thoreau, Civil Disobedience

(The

Washington Post refused to print the ad "on the grounds that it was an implicit exhortation to violate the law", and the

New York Times too, on the grounds that "we do not accept advertising urging readers to perform an illegal action" but thanks to the

Streisand effect the word got out even better that way.)

In 1972,

Jane Hart, wife of

U.S. Senator

Philip Hart, said that she would be resisting the federal income tax. By this time, every major

I.R.S. center had a staff member assigned to be the "Viet Nam Protest Coordinator."

American tax resistance in the 21st Century

Tax

resistance continues continues to be a background theme in American

political discussion, and occasionally tax resistance campaigns break

out in the United States.

The "Don't Buy Bush's War" campaign in 2007–08, organized by

Code Pink to protest the

U.S. War against Iraq, got 2,000 people to sign a tax resistance pledge.

The

Tea Party protests

of 2009 were in part a protest against high taxes (in addition to the

allusion to the Boston Tea Party, the name was supposed to stand for "

Taxed

Enough

Already"). Code Pink even reached out across the ideological aisle to try to find some common ground.

Tax resistance is used in smaller-scale struggles as well. When

23 county officials in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania were charged with

corruption, and the county nonetheless decided to raise taxes by 10%,

residents rebelled. One, Fred Heller, recorded a song in 2010 — "Take

This Tax and Shove It" — to try to rally people to refuse to pay. When a smoking ban in Lansing, Michigan cut into their business, several taverns there launched a tax strike in 2011.

When the Seattle, Washington, City Council introduced a city income tax

in 2017, the state Republican Party did not wait for the tax to be

ruled unconstitutional, but immediately called for "nothing less than

civil disobedience — that is, refusal to comply, file, or pay."

Take this tax and shove it

We ain’t paying you crooks no more

The good ol’ boys stole all our cash

And ran out the courthouse door

— Fred Heller, "Take This Tax and Shove It"