Stress produces numerous physical and mental symptoms which vary according to each individual's situational factors. These can include physical health decline as well as depression. The process of stress management is named as one of the keys to a happy and successful life in modern society. Although life provides numerous demands that can prove difficult to handle, stress management provides a number of ways to manage anxiety and maintain overall well-being.

Despite stress often being thought of as a subjective experience, levels of stress are readily measurable, using various physiological tests, similar to those used in polygraphs.

Many practical stress management techniques are available, some for use by health professionals and others, for self-help, which may help an individual reduce their levels of stress, provide positive feelings of control over one's life and promote general well-being. Other stress reducing techniques involve adding a daily exercise routine, finding a hobby, writing your thoughts, feelings, and moods down and also speaking with a trusted one about what is bothering you. It is very important to keep in mind that not all techniques are going to work the same for everyone, that is why trying different stress managing techniques is crucial in order to find what techniques work best for you. An example of this would be, two people on a roller coaster one can be screaming grabbing on to the bar while the other could be laughing while their hands are up in the air (Nisson). This is a perfect example of how stress effects everyone differently that is why they might need a different treatment. These techniques do not require doctors approval but seeing if a doctors technique works better for you is also very important.

Evaluating the effectiveness of various stress management techniques can be difficult, as limited research currently exists. Consequently, the amount and quality of evidence for the various techniques varies widely. Some are accepted as effective treatments for use in psychotherapy, while others with less evidence favoring them are considered alternative therapies. Many professional organizations exist to promote and provide training in conventional or alternative therapies.

There are several models of stress management, each with distinctive explanations of mechanisms for controlling stress. Much more research is necessary to provide a better understanding of which mechanisms actually operate and are effective in practice.

Historical foundations

Walter Cannon and Hans Selye

used animal studies to establish the earliest scientific basis for the

study of stress. They measured the physiological responses of animals to

external pressures, such as heat and cold, prolonged restraint, and

surgical procedures, then extrapolated from these studies to human

beings.

Subsequent studies of stress in humans by Richard Rahe and others

established the view that stress is caused by distinct, measurable life

stressors, and further, that these life stressors can be ranked by the

median degree of stress they produce (leading to the Holmes and Rahe stress scale).

Thus, stress was traditionally conceptualized to be a result of

external insults beyond the control of those experiencing the stress.

More recently, however, it has been argued that external circumstances

do not have any intrinsic capacity to produce stress, but instead their

effect is mediated by the individual's perceptions, capacities, and

understanding.

Models

The generalized models are:

- The emergency response/fight-or-flight response by Walter Cannon (1914, 1932)

- General Adaptation Syndrome by Hans Selye (1936)

- Stress Model of Henry and Stephens (1977)

- Transactional (or cognitive) Stress Model / stress model of Lazarus after Lazarus (1974)

- Theory of resource conservation by Stevan Hobfoll (1988, 1998; Hobfoll & Buchwald, 2004)

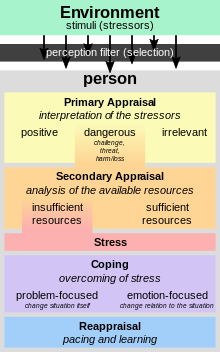

Transactional model

Transactional Model of Stress and Coping of Richard Lazarus

Richard Lazarus

and Susan Folkman suggested in 1981 that stress can be thought of as

resulting from an "imbalance between demands and resources" or as

occurring when "pressure exceeds one's perceived ability to cope".

Stress management was developed and premised on the idea that stress is

not a direct response to a stressor but rather one's resources and

ability to cope mediate the stress response and are amenable to change,

thus allowing stress to be controllable.

Among the many stressors mentioned by employees, these are the most common:

- Conflicts in company

- The way employees are treated by their bosses/supervisors or company

- Lack of job security

- Company policies

- Co-workers who don't do their fair share

- Unclear expectations

- Poor communication

- Not enough control over assignments

- Inadequate pay or benefits

- Urgent deadlines

- Too much work

- Long hours

- Uncomfortable physical conditions

- Relationship conflicts

- Co-workers making careless mistakes

- Dealing with rude customers

- Lack of co-operation

- How the company treats co-workers

In order to develop an effective stress management program, it is

first necessary to identify the factors that are central to a person

controlling his/her stress and to identify the intervention methods

which effectively target these factors. Lazarus and Folkman's

interpretation of stress focuses on the transaction between people and

their external environment (known as the Transactional Model). The model

contends that stress may not be a stressor if the person does not

perceive the stressor as a threat but rather as positive or even

challenging. Also, if the person possesses or can use adequate coping skills,

then stress may not actually be a result or develop because of the

stressor. The model proposes that people can be taught to manage their

stress and cope with their stressors. They may learn to change their

perspective of the stressor and provide them with the ability and

confidence to improve their lives and handle all of the types of

stressors.

Health realization/innate health model

The

health realization/innate health model of stress is also founded on the

idea that stress does not necessarily follow the presence of a

potential stressor. Instead of focusing on the individual's appraisal of

so-called stressors in relation to his or her own coping skills (as the

transactional model does), the health realization model focuses on the

nature of thought, stating that it is ultimately a person's thought

processes that determine the response to potentially stressful external

circumstances. In this model, stress results from appraising oneself and

one's circumstances through a mental filter of insecurity and

negativity, whereas a feeling of well-being results from approaching the world with a "quiet mind".

This model proposes that helping stressed individuals understand

the nature of thought—especially providing them with the ability to

recognize when they are in the grip of insecure thinking, disengage from

it, and access natural positive feelings—will reduce their stress.

Techniques

High demand levels load the person with extra effort and work. A new time schedule

is worked up, and until the period of abnormally high, personal demand

has passed, the normal frequency and duration of former schedules is

limited.

Many techniques cope

with the stresses life brings. Some of the following ways reduce a

lower than usual stress level, temporarily, to compensate the biological issues involved; others face the stressor at a higher level of abstraction:

- Autogenic training

- Social activity

- Cognitive therapy

- Conflict resolution

- Cranial release technique

- Getting a hobby

- Meditation

- Mindfulness

- Music as a coping strategy

- Deep breathing

- Yoga Nidra

- Nootropics

- Reading novels

- Prayer

- Relaxation techniques

- Artistic expression

- Fractional relaxation

- Humour

- Physical exercise

- Progressive relaxation

- Spas

- Somatics training

- Spending time in nature

- Stress balls

- Natural medicine

- Clinically validated alternative treatments

- Time management

- Planning and decision making

- Listening to certain types of relaxing music

- Spending quality time with pets

Techniques of stress management will vary according to the philosophical paradigm.

Stress prevention and resilience

Although

many techniques have traditionally been developed to deal with the

consequences of stress, considerable research has also been conducted on

the prevention of stress, a subject closely related to psychological resilience-building.

A number of self-help approaches to stress-prevention and

resilience-building have been developed, drawing mainly on the theory

and practice of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Measuring stress

Levels of stress can be measured. One way is through the use of psychological testing: The Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale [two scales of measuring stress] is used to rate stressful life events, while the DASS [Depression Anxiety Stress Scales] contains a scale for stress based on self-report items. Changes in blood pressure and galvanic skin response can also be measured to test stress levels, and changes in stress levels. A digital thermometer can be used to evaluate changes in skin temperature, which can indicate activation of the fight-or-flight response

drawing blood away from the extremities. Cortisol is the main hormone

released during a stress response and measuring cortisol from hair will

give a 60- to 90-day baseline stress level of an individual. This

method of measuring stress is currently the most popular method in the

clinic.

Effectiveness

Stress management has physiological and immune benefits.

Positive outcomes are observed using a combination of non-drug interventions:

- treatment of anger or hostility,

- autogenic training

- talking therapy (around relationship or existential issues)

- biofeedback

- cognitive therapy for anxiety or clinical depression

Types of stress

Acute stress

Acute stress is the most common form of stress among humans worldwide.

Acute stress deals with the pressures of the near future or

dealing with the very recent past. This type of stress is often

misinterpreted for being a negative connotation. While this is the case

in some circumstances, it is also a good thing to have some acute stress

in life. Running or any other form of exercise is considered an acute

stressor. Some exciting or exhilarating experiences such as riding a

roller coaster is an acute stress but is usually very enjoyable. Acute

stress is a short term stress and as a result, does not have enough time

to do the damage that long term stress causes.

Chronic stress

Chronic stress

is unlike acute stress. It has a wearing effect on people that can

become a very serious health risk if it continues over a long period of

time. Chronic stress can lead to memory loss,

damage spatial recognition and produce a decreased drive of eating. The

severity varies from person to person and also gender difference can be

an underlying factor. Women are able to take longer durations of stress

than men without showing the same maladaptive changes. Men can deal

with shorter stress duration better than women can but once males hit a

certain threshold, the chances of them developing mental issues

increases drastically.

Workplace

Stress in the workplace is a commonality throughout the world in every business. Managing that stress becomes vital in order to keep up job performance as well as relationship with co-workers and employers.

For some workers, changing the work environment relieves work stress.

Making the environment less competitive between employees decreases some

amounts of stress. However, each person is different and some people

like the pressure to perform better.

Salary can be an important concern of employees. Salary can

affect the way people work because they can aim for promotion and in

result, a higher salary. This can lead to chronic stress.

Cultural differences have also shown to have some major effects

on stress coping problems. Eastern Asian employees may deal with certain

work situations differently from how a Western North American employee

would.

In order to manage stress in the workplace, employers can provide stress managing programs such as therapy, communication programs, and a more flexible work schedule.

Medical environment

A

study was done on the stress levels in general practitioners and

hospital consultants in 1999. Over 500 medical employees participated in

this study done by R.P Caplan. These results showed that 47% of the

workers scored high on their questionnaire for high levels of stress.

27% of the general practitioners even scored to be very depressed. These

numbers came to a surprise to Dr. Caplan and it showed how alarming the

large number of medical workers become stressed out because of their

jobs. Managers stress levels were not as high as the actual

practitioners themselves. An eye opening statistic showed that nearly

54% of workers suffered from anxiety while being in the hospital.

Although this was a small sample size for hospitals around the world,

Caplan feels this trend is probably fairly accurate across the majority

of hospitals.

Stress management programs

Many

businesses today have begun to use stress management programs for

employees who are having trouble adapting to stress at the workplace or

at home. Some companies provide special equipments adapting to stress at

the workplace to their employees, like coloring diaries and stress relieving gadgets.

Many people have spill over stress from home into their working

environment. There are a couple of ways businesses today try to

alleviate stress on their employees. One way is individual intervention.

This starts off by monitoring the stressors in the individual. After

monitoring what causes the stress, next is attacking that stressor and

trying to figure out ways to alleviate them in any way. Developing

social support is vital in individual intervention, being with others to

help you cope has proven to be a very effective way to avoid stress.

Avoiding the stressors altogether is the best possible way to get rid of

stress but that is very difficult to do in the workplace. Changing

behavioral patterns, may in turn, help reduce some of the stress that is

put on at work as well.

Employee assistance programs

can include in-house counseling programs on managing stress. Evaluative

research has been conducted on EAPs that teach individual stress

control and inoculation techniques such as relaxation, biofeedback, and

cognitive restructuring. Studies show that these programs can reduce the

level of physiological arousal associated with high stress.

Participants who master behavioral and cognitive stress-relief

techniques report less tension, fewer sleep disturbances, and an

improved ability to cope with workplace stressors.

Another way of reducing stress at work is by simply changing the

workload for an employee. Some may be too overwhelmed that they have so

much work to get done, or some also may have such little work that they

are not sure what to do with themselves at work. Improving

communications between employees also sounds like a simple approach, but

it is very effective for helping reduce stress. Sometimes making the

employee feel like they are a bigger part of the company, such as giving

them a voice in bigger situations shows that you trust them and value

their opinion. Having all the employees mesh well together is a very

underlying factor which can take away much of workplace stress. If

employees fit well together and feed off of each other, the chances of

lots of stress is very minimal. Lastly, changing the physical qualities

of the workplace may reduce stress. Changing things such as the

lighting, air temperature, odor, and up to date technology.

Intervention is broken down into three steps: primary, secondary,

tertiary. Primary deals with eliminating the stressors altogether.

Secondary deals with detecting stress and figuring out ways to cope with

it and improving stress management skills. Finally, tertiary deals with

recovery and rehabbing the stress altogether. These three steps are

usually the most effective way to deal with stress not just in the

workplace, but overall.

Aviation industry

Aviation is a high-stress industry,

given that it requires a high level of precision at all times.

Chronically high stress levels can ultimately decrease the performance

and compromise safety.

To be effective, stress measurement tools must be specific to the

aviation industry, given its unique working environment and other stressors. Stress measurement in aviation seeks to quantify the psychological stress experienced by aviators, with the goal of making needed improvements to aviators' coping and stress management skills.

To more precisely measure stress, aviators' many responsibilities

are broken down into "workloads." This helps to categorise the broad

concept of "stress" by specific stressors.

Additionally, since different workloads may pose unique stressors,

this method may be more effective than measuring stress levels as a

whole. Stress measurement tools can then help aviators identify which

stressors are most problematic for them, and help them improve on

managing workloads, planning tasks, and coping with stress more

effectively.

To evaluate workload, a number of tools can be used. The major types of measurement tools are:

- Performance-based measures;

- Subjective measures, like questionnaires which aviators answer themselves; and

- Physiological measures, like measurement of heart rate.

Implementation of evaluation tools requires time, instruments for measurement, and software for collecting data.

Measurement systems

The most commonly used stress measurement systems are primarily rating scale-based.

These systems tend to be complex, containing multiple levels with a

variety of sections, to attempt to capture the many stressors present in

the aviation industry. Different systems may be utilised in different

operational specialties.

- The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) – The PSS is a widely used subjective tool for measuring stress levels. It consists of 10 questions, and asks participants to rate, on a five-point scale, how stressed they felt after a certain event. All 10 questions are summed to obtain a total score from 0 to 40. In the aviation industry, for example, it has been used with flight training students to measure how stressed they felt after flight training exercises.

- The Coping Skills Inventory – This inventory measures aviators' skills for coping with stress. This is another subjective measure, asking participants to rate, on a five-point scale, the extent to which they use eight common coping skills: Substance abuse, Emotional support, Instrumental support (help with tangible things, like child care, finances, or task sharing), Positive reframing (changing one's thinking about a negative event, and thinking of it as a positive instead), Self-blame, Planning, Humour and Religion. An individual's total score indicates the extent to which he or she is using effective, positive coping skills (like humor and emotional support); ineffective, negative coping skills (like substance abuse and self-blame); and where the individual could improve.

- The Subjective Workload Assessment Technique (SWAT) – SWAT is a rating system used to measure individuals' perceived mental workload while performing a task, like developing instruments in a lab, multitasking aircraft duties, or conducting air defense. SWAT combines measurements and scaling techniques to develop a global rating scale.

Pilot stress report systems

Early pilot stress report systems were adapted and modified from existing psychological questionnaires and surveys.

The data from these pilot-specific surveys is then processed and

analyzed through an aviation-focused system or scale. Pilot-oriented

questionnaires are generally designed to study work stress or home

stress.

Self-report can also be used to measure a combination of home stress,

work stress, and perceived performance. A study conducted by Fiedler,

Della Rocco, Schroeder and Nguyen (2000) used Sloan and Cooper's

modification of the Alkov questionnaire to explore aviators' perceptions

of the relationship between different types of stress. The results

indicated that pilots believed performance was impaired when home stress

carried over to the work environment. The degree of home stress that

carried over to work environment was significantly and negatively

related to flying performance items, such as planning, control, and

accuracy of landings. The questionnaire was able to reflect pilots'

retroactive perceptions and the accuracy of these perceptions.

Alkov, Borowsky, and Gaynor started a 22-item questionnaire for U.S. Naval aviators in 1982 to test the hypothesis that inadequate stress coping strategies contributed to flight mishaps.

The questionnaire consists of items related to lifestyle changes and

personality characteristics. After completing the questionnaire, the

test group is divided into two groups: "at-fault" with mishap, and

"not-at-fault" in a mishap. Then, questionnaires from these two groups

were analyzed to examine differences. A study of British commercial airline pilots, conducted by Sloan and Cooper (1986), surveyed 1,000 pilot members from the British Airline Pilots' Association

(BALPA). They used a modified version of Alkov, Borowsky, and Gaynor's

questionnaire to collect data on pilots' perceptions of the

relationship between stress and performance. Being a subjective

measure, this study's data was based on pilots' perceptions, and thus

rely on how accurately they recall past experiences their relationships

to stress. Despite relying on subjective perceptions and memories, the

study showed that pilot reports are noteworthy.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is another scale used in many industries, including the mental health professions, to screen for depressive symptoms.

Parsa and Kapadia (1997) used the BDI to survey a group of 57 U.S. Air Force fighter pilots who had flown combat operations.

The adaptation of the BDI to the aviation field was problematic.

However, the study revealed some unexpected findings. The results

indicated that 89% of the pilots reported insomnia; 86% reported

irritability; 63%, dissatisfaction; 38%, guilt; and 35%, loss of libido. 50% of two squadrons

and 33% of another squadron scored above 9 on the BDI, suggesting at

least low levels of depression. Such measurement may be difficult to

interpret accurately.