Paul Kurtz

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Paul Winter Kurtz

December 21, 1925

Newark, New Jersey, United States

|

| Died | October 20, 2012 (aged 86) |

| Alma mater | New York University Columbia University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| School | Scientific skepticism, secular humanism |

Main interests

| Philosophy of religion, Secularism, philosophical naturalism |

Paul Kurtz (December 21, 1925 – October 20, 2012) was a prominent American scientific skeptic and secular humanist. He has been called "the father of secular humanism". He was Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo, having previously also taught at Vassar, Trinity, and Union colleges, and the New School for Social Research.

Kurtz founded the publishing house Prometheus Books in 1969. He was also the founder and past chairman of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI, formerly the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, CSICOP), the Council for Secular Humanism, and the Center for Inquiry. He was editor in chief of Free Inquiry magazine, a publication of the Council for Secular Humanism.

He was co-chair of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) from 1986 to 1994. He was a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Humanist Laureate, president of the International Academy of Humanism and Honorary Associate of Rationalist International. As a member of the American Humanist Association, he contributed to the writing of Humanist Manifesto II. He was an editor of The Humanist, 1967–78.

Kurtz published over 800 articles or reviews and authored and edited over 50 books. Many of his books have been translated into over 60 languages.

Early years

Kurtz was born in Newark, New Jersey, into a Jewish family, the son of Sara Lasser and Martin Kurtz. Kurtz received his bachelor's degree from New York University, and the Master's degree and Doctor of Philosophy degree from Columbia University. Kurtz was left-wing in his youth, but has said that serving in the United States Army in World War II taught him the dangers of ideology. He saw the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps after they were liberated, and became disillusioned with Communism when he encountered Russian slave laborers who had been taken to Nazi Germany by force but refused to return to the Soviet Union at the end of the war.

Kurtz addresses the Banquet at the 1983 CSICOP Conference in Buffalo, NY

Secular humanism

Kurtz was largely responsible for the secularization of humanism. Before Kurtz embraced the term "secular humanism,"

which had received wide publicity through fundamentalist Christians in

the 1980s, humanism was more widely perceived as a religion (or a pseudoreligion) that did not include the supernatural. This can be seen in the first article of the original Humanist Manifesto which refers to "Religious Humanists" and by Charles and Clara Potter's influential 1930 book Humanism: A New Religion.

Kurtz used the publicity generated by fundamentalist preachers to grow the membership of the Council for Secular Humanism, as well as strip the religious aspects found in the earlier humanist movement. He founded the Center for Inquiry in 1991. There are now some 40 Centers and Communities

worldwide, including in Los Angeles, Washington, New York City, London,

Amsterdam, Warsaw, Moscow, Beijing, Hyderabad, Toronto, Dakar, Buenos

Aires and Kathmandu.

In 1999 Kurtz was given the International Humanist Award by the International Humanist and Ethical Union. He had been a board member of IHEU between 1969 and 1994, and in a tribute by former colleague at both IHEU and the Council for Secular Humanism

Matt Cherry, Kurtz was described as having "had a strong commitment to

international humanism – a commitment to humanism beyond US borders

never seen matched by another American. He did a lot to expand IHEU as a

member of the IHEU Growth and Development Committee (with Levi Fragell and Rob Tielman) and then when he was co-chair, also with Rob and Levi. He always pushed IHEU to be bigger and bolder."

In 2000 he received the International Rationalist Award by Rationalist International. In 2001, he debated Christian philosopher William Lane Craig over the nature of morality.

Kurtz believed that the nonreligious members of the community should take a positive view on life. Religious skepticism, according to Paul Kurtz, is only one aspect of the secular humanistic outlook. In an interview with D.J. Grothe, he stated that a categorical imperative of secular humanism is "genuine concern for the well-being of other humans."

At the Council of Secular Humanism's Los Angeles conference (7–10

October 2010), tension over the future of humanism was on display as

Kurtz urged a more accommodationist approach to religion while his

successors argued for a more adversarial approach.

On May 18, 2010, he resigned from all these positions. Moreover, the Center for Inquiry accepted his resignation as chairman emeritus, board member, and as editor in chief of Free Inquiry

as being the culmination of a years-long "leadership transition",

thanking him "for his decades of service" while also alluding to

"concerns about Dr. Kurtz's day-to-day management of the organization". Kurtz renewed his efforts in organized humanism by founding The Institute for Science and Human Values and its journal The Human Prospect: A NeoHumanist Perspective in June 2010.

Critique of the paranormal

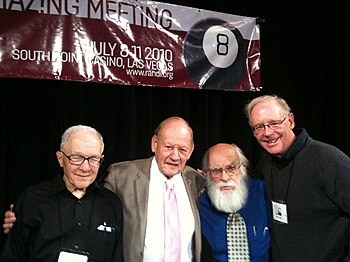

Ray Hyman, Paul Kurtz, James Randi, and Ken Frazier at TAM8, July 2010, Las Vegas, after their session on the history of the modern skeptical movement

Another aspect in Kurtz's legacy is his critique of the paranormal. In 1976, CSICOP started Skeptical Inquirer, its official journal. Like Martin Gardner, Carl Sagan, Isaac Asimov, James Randi, Ray Hyman and others, Kurtz has popularized scientific skepticism and critical thinking about claims of the paranormal.

Concerning the founding of the modern skeptical movement, Ray

Hyman states that in 1972, he, along with James Randi and Martin

Gardner, wanted to form a skeptical group called S.I.R. (Sanity In

Research). The three of them felt they had no administration experience,

saying "we just had good ideas", and were soon joined by Marcello Truzzi who provided structure for the group. Truzzi involved Paul Kurtz and they together formed CSICOP in 1976.

Kurtz wrote:

[An] explanation for the persistence of the paranormal, I submit, is due to the transcendental temptation. In my book by that name, I present the thesis that paranormal and religious phenomena have similar functions in human experience; they are expressions of a tendency to accept magical thinking. This temptation has such profound roots within human experience and culture that it constantly reasserts itself.

In The Transcendental Temptation, Kurtz analyzes how provable are the claims of Jesus, Moses, and Muhammad, as well as the founders of religions on American soil such as Joseph Smith and Ellen White. He also evaluates the activities of the most famous modern psychics and what he believes are the fruitless researches of parapsychologists. The Transcendental Temptation is considered among Kurtz's most influential writings.

He promoted what he called "Skepticism of the Third Kind," in

which skeptics actively investigate claims of the paranormal, rather

than just question them. He saw this type of skepticism as distinct from

the "first kind" of extreme philosophical skepticism,

which questions the possibility that anything can be known, as well as

the "second kind" of skepticism, which accepts that knowledge of the

real world is possible but is still largely a philosophical exercise.

On 19 April 2007, Kurtz appeared on Penn & Teller's television show Bullshit! arguing that exorcism and Satanic cults are merely "hype and paranoia".

The office of Paul Kurtz at Center for Inquiry Transnational, Amherst, NY

Eupraxsophy

Kurtz coined the term eupraxsophy (originally eupraxophy) to refer to philosophies or life stances such as secular humanism and Confucianism that do not rely on belief in the transcendent or supernatural. A eupraxsophy is a nonreligious life stance or worldview emphasizing the importance of living an ethical and exuberant life, and relying on rational methods such as logic, observation and science (rather than faith, mysticism or revelation)

toward that end. The word is based on the Greek words for "good",

"practice", and "wisdom". Eupraxsophies, like religions, are cosmic in

their outlook but eschew the supernatural component of religion,

avoiding the "transcendental temptation," as Kurtz puts it. Although

critical of supernatural religion, he has attempted to develop

affirmative ethical values of naturalistic humanism.

The Paul Kurtz Lecture Series

In June 2010, the State University of New York at Buffalo

announced the establishment of the Paul Kurtz Lecture Series. The

series will bring notable speakers to the University's campus in

Amherst, New York, to speak on topics relevant to the philosophy of

humanism and philosophical naturalism. Kurtz had made the bequest and

charitable gift annuity to the University, where he taught from 1965 to

1991, to help promote the development of critical intelligence in future

generations of SUNY at Buffalo students. On November 5, 2010, the

University announced that cognitive scientist Steven Pinker would inaugurate the new Paul Kurtz Lecture Series on December 2, 2010.

Institute for Science and Human Values

Paul Kurtz conceived of the Institute for Science and Human Values

in 2009 as yet another branch of the umbrella group, the Center for

Inquiry. Upon his resignation from the Center for Inquiry he launched

the Institute for Science and Human Values as a separate entity.

In ISHV's first press release Kurtz said ISHV hoped to "rehumanize

secularism" and "find out how to better develop the common moral virtues

that we share as human beings." Kurtz was editor-in-chief of ISHV's journal, The Human Prospect: A NeoHumanist Perspective.

Honors

The asteroid 6629 Kurtz was named in his honor.

At a meeting of the executive council of CSI in Denver, Colorado

in April 2011, Kurtz was selected for inclusion in CSI's Pantheon of

Skeptics. The Pantheon of Skeptics was created by CSI to remember the

legacy of deceased fellows of CSI and their contributions to the cause

of scientific skepticism.

Gallery

- Philosopher Paul Kurtz (left) and author Martin Gardner at a CSICOP executive council meeting in 1979

- UFO Panel at the 1983 CSICOP Conference, Buffalo, NY with Robert Sheaffer (far right).

Bibliography

- The Humanist Alternative (Paul Kurtz, editor), 1973, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-013-8

- Exuberance: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life 1978, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-293-9

- A Secular Humanist Declaration 1980, ISBN 0-87975-149-5

- Sidney Hook: Philosopher of Democracy and Humanism 1983, ISBN 0-87975-191-6

- In Defense of Secular Humanism 1983, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-228-9

- The Transcendental Temptation: A Critique of Religion and the Paranormal, 1986 ISBN 0-87975-645-4

- A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology (Paul Kurtz, editor), 1985, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-300-5

- Forbidden Fruit: The Ethics of Humanism, 1988, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-455-9

- The New Skepticism: Inquiry and Reliable Knowledge, 1992, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-766-3

- Challenges to the Enlightenment: In Defense of Reason and Science by Paul Kurtz, et al., 1994 ISBN 0-87975-869-4

- Living Without Religion: Eupraxophy, 1994, Prometheus Books, ISBN 0-87975-929-1

- Toward a New Enlightenment: The Philosophy of Paul Kurtz (Tim Madigan, editor; Vern Bullough, Introduction), 1994, Transaction, ISBN 1-56000-118-6

- The Courage to Become, 1997, Praeger/Greenwood, ISBN 0-275-96016-1

- Embracing the Power of Humanism, 2000, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-8476-9966-8

- Humanist Manifesto 2000, 2000, ISBN 1-57392-783-X

- Skepticism and Humanism: The New Paradigm, 2001 ISBN 0-7658-0051-9

- Science and Religion by Paul Kurtz, et al., 2003 ISBN 1-59102-064-6

- Affirmations: Joyful And Creative Exuberance, 2004 ISBN 1-59102-265-7

- What Is Secular Humanism?, 2006 ISBN 1-59102-499-4

- The Turbulent Universe, 2013, Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-61614-735-8