From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The European colonization of the Americas describes the history of the settlement and establishment of control of the continents of the Americas by most of the naval powers of Western Europe.

The European colonization of the Americas describes the history of the settlement and establishment of control of the continents of the Americas by most of the naval powers of Western Europe.

Political map of the America in 1794

Spanish conquistador style armour

American Discovery Viewed by Native Americans (Thomas Hart Benton, 1922). European "discovery" and colonization would have disastrous effects on the indigenous peoples of the Americas and their societies.

Systematic European colonization began in 1492, when a Spanish expedition headed by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus sailed west to find a new trade route to the Far East but inadvertently landed in what came to be known to Europeans as the "New World". He ran aground on the northern part of Hispaniola on 5 December 1492, which the Taino people

had inhabited since the 9th century; the site became the first

permanent European settlement in the Americas. Western European

conquest, large-scale exploration and colonization soon followed.

Columbus's first two voyages (1492–93) reached the Bahamas and various Caribbean islands, including Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Cuba. In 1497, Italian explorer John Cabot, on behalf of England, landed on the North American coast, and a year later, Columbus's third voyage reached the South American coast. As the sponsor of Christopher Columbus's voyages, Spain

was the first European power to settle and colonize the largest areas,

from North America and the Caribbean to the southern tip of South

America.

The Spaniards began building their American empire in the Caribbean, using islands such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola as bases. The North and South American mainland fell to the conquistadors, with an estimated 8,000,000 deaths of indigenous populations, which has been argued to be the first large-scale act of genocide in the modern era. Florida fell to Juan Ponce de León after 1513. From 1519 to 1521, Hernán Cortés waged a campaign against the Aztec Empire, ruled by Moctezuma II. The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, became Mexico City, the chief city of what the Spanish were now calling "New Spain". More than 240,000 Aztecs died during the siege of Tenochtitlan. Of these, 100,000 died in combat. Between 500 and 1,000 of the Spaniards engaged in the conquest died. Later, the areas that are today California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Missouri, Louisiana, and Alabama were taken over by other conquistadors, such as Hernando de Soto, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Farther to the south, Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire

during the 1530s. The de Soto expedition was the first major encounter

of Europeans with North American Indians in the eastern half of the

United States. The expedition journeyed from Florida through present-day

Georgia and the Carolinas, then west across the Mississippi and into Texas. De Soto fought his biggest battle

at the walled town of Mabila in present-day Alabama on October 18,

1540. Spanish losses were 22 killed and 148 wounded. The Spaniards

claimed that 2,500 Indians died. If true, Mabila was the bloodiest

battle ever fought between native Americans and Europeans in the

present-day United States. The centuries of continuous conflicts

between the North American Indians and the Anglo-Americans were

secondary to the devastation wrought on the densely populated

Meso-American, Andean, and Caribbean heartlands.

The British colonization of the Americas started with the unsuccessful settlement attempts in Roanoke and Newfoundland. The English eventually went on to control much of Eastern North America, The Caribbean, and parts of South America. The British also gained Florida and Quebec in the French and Indian War.

Other powers such as France

also founded colonies in the Americas: in eastern North America, a

number of Caribbean islands and small coastal parts of South America. Portugal colonized Brazil, tried colonizing the eastern coasts of present-day Canada and settled for extended periods northwest (on the east bank) of the River Plate. The Age of Exploration was the beginning of territorial expansion for several European countries. Europe had been preoccupied with internal wars and was slowly recovering from the loss of population caused by the Black Death; thus the rapid rate at which it grew in wealth and power was unforeseeable in the early 15th century.

Eventually, most of the Western Hemisphere

came under the control of Western European governments, leading to

changes to its landscape, population, and plant and animal life. In the

19th century over 50 million people left Western Europe for the

Americas. The post-1492 era is known as the period of the Columbian Exchange, a dramatically widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations (including slaves), ideas, and communicable disease between the American and Afro-Eurasian hemispheres following Columbus's voyages to the Americas.

Henry F. Dobyns estimates that immediately before European

colonization of the Americas there were between 90 and 112 million

people in the Americas; a larger population than Europe at the same

time.

Norse trans-oceanic contact

Voyages of the Vikings to America.

Norse journeys to Greenland and Canada are supported by historical and archaeological evidence. A Norse colony in Greenland was established in the late 10th century, and lasted until the mid 15th century, with court and parliament assemblies (þing) taking place at Brattahlíð and a bishop located at Garðar. The remains of a Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, were discovered in 1960 and were dated to around the year 1000 (carbon dating estimate 990–1050 CE). L'Anse aux Meadows is the only site widely accepted as evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It was named a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1978. It is also notable for its possible connection with the attempted colony of Vinland, established by Leif Erikson around the same period or, more broadly, with the Norse colonization of the Americas.

Early conquests, claims and colonies

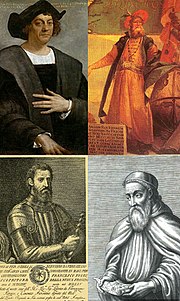

Italian explorers who played a key role in the European colonization of the Americas (clockwise from top): Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, Amerigo Vespucci and Giovanni da Verrazzano

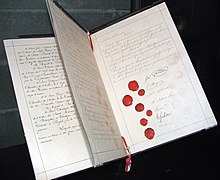

Early explorations and conquests were made by the Spanish and the Portuguese immediately following their own final reconquest of Iberia in 1492. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas,

ratified by the Pope, these two kingdoms divided the entire

non-European world into two areas of exploration and colonization, with a

north to south boundary that cut through the Atlantic Ocean and the

eastern part of present-day Brazil. Based on this treaty and on early

claims by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa, discoverer of the Pacific Ocean in 1513, the Spanish conquered large territories in North, Central and South America.

Territorial evolution of North America of non-native nation states from 1750 to 2008

Central America & Caribbean sovereignty 1700–present

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés took over the Aztec Kingdom and Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire. As a result, by the mid-16th century, the Spanish Crown had gained control of much of western South America, and southern North America, in addition to its earlier Caribbean territories. Over this same timeframe, Portugal claimed lands in North America (Canada) and colonized much of eastern South America, naming it Santa Cruz and Brazil.

Spanish and Portuguese empires in 1790.

Other European nations soon disputed the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas. England and France

attempted to plant colonies in the Americas in the 16th century, but

these failed. England and France succeeded in establishing permanent

colonies in the following century, along with the Dutch Republic.

Some of these were on Caribbean islands, which had often already been

conquered by the Spanish or depopulated by disease, while others were in

eastern North America, which had not been colonized by Spain north of Florida.

Early European possessions in North America included Spanish Florida, Spanish New Mexico, the English colonies of Virginia (with its North Atlantic offshoot, Bermuda) and New England, the French colonies of Acadia and Canada, the Swedish colony of New Sweden, and the Dutch New Netherland. In the 18th century, Denmark–Norway revived its former colonies in Greenland, while the Russian Empire gained a foothold in Alaska. Denmark-Norway would later make several claims in the Caribbean, starting in the 1600s.

As more nations gained an interest in the colonization of the

Americas, competition for territory became increasingly fierce.

Colonists often faced the threat of attacks from neighboring colonies,

as well as from indigenous tribes and pirates.

Early state-sponsored colonists

The first phase of well-financed European activity in the Americas

began with the Atlantic Ocean crossings of Christopher Columbus

(1492–1504), sponsored by Spain, whose original attempt was to find a

new route to India and China, known as "the Indies". He was followed by other explorers such as John Cabot, who was sponsored by England and reached Newfoundland. Pedro Álvares Cabral reached Brazil and claimed it for Portugal.

Amerigo Vespucci, working for Portugal in voyages from 1497 to 1513, established that Columbus had reached a new set of continents. Cartographers still use a Latinized version of his first name, America, for the two continents. Other explorers included Giovanni da Verrazzano, sponsored by France in 1524; the Portuguese João Vaz Corte-Real in Newfoundland; João Fernandes Lavrador, Gaspar and Miguel Corte-Real and João Álvares Fagundes, in Newfoundland, Greenland, Labrador, and Nova Scotia (from 1498 to 1502, and in 1520); Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), Henry Hudson (1560s–1611), and Samuel de Champlain (1567–1635), who explored the region of Canada he reestablished as New France.

In 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama and led the first European expedition to see the Pacific Ocean from the west coast of the New World.

In an action with enduring historical import, Balboa claimed the

Pacific Ocean and all the lands adjoining it for the Spanish Crown. It

was 1517 before another expedition, from Cuba, visited Central America, landing on the coast of Yucatán in search of slaves.

Spanish/Portuguese colonies

These explorations were followed, notably in the case of Spain, by a phase of conquest: The Spaniards, having just finished the Reconquista

of Spain from Muslim rule, were the first to colonize the Americas,

applying the same model of governing their European holdings to their

territories of the New World.

Ten years after Columbus's discovery, the administration of Hispaniola was given to Nicolás de Ovando of the Order of Alcántara, founded during the Reconquista. As in the Iberian Peninsula, the inhabitants of Hispaniola were given new landmasters, while religious orders handled the local administration. Progressively the encomienda system, which granted tribute (access to indigenous labor and taxation) to European settlers, was set in place.

A relatively common misconception is that a small number of conquistadores conquered vast territories, aided only by disease epidemics and their powerful caballeros.

In fact, recent archaeological excavations have suggested a vast

Spanish-Indian alliance numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Hernán Cortés eventually conquered Mexico with the help of Tlaxcala in 1519–1521, while the conquest of the Incas was supported by some 40,000 Incan renegades led by Francisco Pizarro in between 1532 and 1535.

Over the 1st century and a half after Columbus's voyages, the

native population of the Americas plummeted by an estimated 80% (from

around 50 million in 1492 to eight million in 1650), mostly by outbreaks of Old World diseases.

In 1532, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor sent a vice-king to Mexico, Antonio de Mendoza,

in order to prevent Cortes' independentist drives, who definitively

returned to Spain in 1540. Two years later, Charles V signed the New Laws (which replaced the Laws of Burgos of 1512) prohibiting slavery and the repartimientos, but also claiming as his own all the American lands and all of the indigenous people as his own subjects.

Painting depicting a Castas with his mixed-race daughter and his Mulatta wife by Miguel Cabrera, 1763

When Pope Alexander VI issued the Inter caetera bull in May 1493 granting the new lands to the Kingdom of Spain, he requested in exchange an evangelization of the people. Thus, during Columbus's second voyage, Benedictine monks accompanied him, along with twelve other priests. As slavery

was prohibited between Christians, and could only be imposed in

non-Christian prisoners of war or on men already sold as slaves, the

debate on Christianization was particularly acute during the 16th

century. In 1537, the papal bull Sublimis Deus

definitively recognized that Native Americans possessed souls, thus

prohibiting their enslavement, without putting an end to the debate.

Some claimed that a native who had rebelled and then been captured could

be enslaved nonetheless.

Later, the Valladolid debate between the Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas and another Dominican philosopher Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda was held, with the former arguing that Native Americans were beings doted with souls, as all other human beings, while the latter argued to the contrary and justified their enslavement.

The process of Christianization was at first violent: when the first Franciscans arrived in Mexico in 1524, they burned the places dedicated to pagan cult, alienating much of the local population.

In the 1530s, they began to adapt Christian practices to local customs,

including the building of new churches on the sites of ancient places

of worship, leading to a mix of Old World Christianity with local

religions. The Spanish Roman Catholic Church, needing the natives' labor and cooperation, evangelized in Quechua, Nahuatl, Guaraní and other Native American languages, contributing to the expansion of these indigenous languages and equipping some of them with writing systems. One of the first primitive schools for Native Americans was founded by Fray Pedro de Gante in 1523.

To reward their troops, the Conquistadores often allotted

Indian towns to their troops and officers. Black African slaves were

introduced to substitute for Native American labor in some

locations—including the West Indies, where the indigenous population was nearing extinction on many islands.

During this time, the Portuguese gradually switched from an initial plan of establishing trading posts to extensive colonization

of what is now Brazil. They imported millions of slaves to run their

plantations. The Portuguese and Spanish royal governments expected to

rule these settlements and collect at least 20% of all treasure found

(the quinto real collected by the Casa de Contratación), in addition to collecting all the taxes they could. By the late 16th century American silver accounted for one-fifth of Spain's total budget. In the 16th century perhaps 240,000 Europeans entered American ports.

The search for riches

Fur traders in Canada, trading with people of Indigenous ancestry, 1777

Inspired by the Spanish riches from colonies founded upon the conquest of the Aztecs, Incas,

and other large Native American populations in the 16th century, the

first Englishmen to settle permanently in America hoped for some of the

same rich discoveries when they established their first permanent

settlement in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. They were sponsored by common stock companies such as the chartered Virginia Company

financed by wealthy Englishmen who exaggerated the economic potential

of this new land. The main purpose of this colony was the hope of

finding gold.

It took strong leaders, like John Smith,

to convince the colonists of Jamestown that searching for gold was not

taking care of their immediate needs for food and shelter and the biblical principle that "he who will not work shall not eat" (see 2 Thessalonians 3). The lack of food security

leading to extremely high mortality rate was quite distressing and

cause for despair among the colonists. To support the Colony, numerous supply missions were organized. Tobacco later became a cash crop, with the work of John Rolfe and others, for export and the sustaining economic driver of Virginia and the neighboring colony of Maryland.

From the beginning of Virginia's settlements in 1587 until the

1680s, the main source of labor and a large portion of the immigrants

were indentured servants

looking for new life in the overseas colonies. During the 17th century,

indentured servants constituted three-quarters of all European

immigrants to the Chesapeake region. Most of the indentured servants

were teenagers from England with poor economic prospects at home. Their

fathers signed the papers that gave them free passage to America and an

unpaid job until they became of age. They were given food, clothing,

housing and taught farming or household skills. American landowners were

in need of laborers and were willing to pay for a laborer’s passage to

America if they served them for several years. By selling passage for

five to seven years worth of work, they could then start on their own in

America. Many of the migrants from England died in the first few years.

Economic advantage also prompted the Darien Scheme, an ill-fated venture by the Kingdom of Scotland to settle the Isthmus of Panama

in the late 1690s. The Darien Scheme aimed to control trade through

that part of the world and thereby promote Scotland into a world trading

power. However, it was doomed by poor planning, short provisions, weak

leadership, lack of demand for trade goods, and devastating disease. The failure of the Darien Scheme was one of the factors that led the Kingdom of Scotland into the Act of Union 1707 with the Kingdom of England creating the united Kingdom of Great Britain and giving Scotland commercial access to English, now British, colonies.

In the French colonial regions, the focus of economy was on sugar plantations in Caribbean. In Canada the fur trade

with the natives was important. About 16,000 French men and women

became colonizers. The great majority became subsistence farmers along

the St. Lawrence River.

With a favorable disease environment and plenty of land and food, their

numbers grew exponentially to 65,000 by 1760. Their colony was taken

over by Britain in 1760, but social, religious, legal, cultural and

economic changes were few in a society that clung tightly to its

recently formed traditions.

Religious immigration

Penn's Treaty with the Indians

Roman Catholics were the first major religious group to immigrate to the New World,

as settlers in the colonies of Portugal and Spain (and later, France)

belonged to that faith. English and Dutch colonies, on the other hand,

tended to be more religiously diverse. Settlers to these colonies

included Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, English Puritans and other nonconformists, English Catholics, Scottish Presbyterians, French Huguenots, German and Swedish Lutherans, as well as Jews, Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, and Moravians.

Many groups of colonists went to the Americas searching for the right to practice their religion without persecution. The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century broke the unity of Western Christendom

and led to the formation of numerous new religious sects, which often

faced persecution by governmental authorities. In England, many people

came to question the organization of the Church of England by the end of the 16th century. One of the primary manifestations of this was the Puritan movement, which sought to "purify" the existing Church of England of its offensive residual Catholic rites.

Waves of repression led to the migration of about 20,000 Puritans to New England between 1629 and 1642, where they founded multiple colonies. Later in the century, the new Pennsylvania colony was given to William Penn

in settlement of a debt the king owed his father. Its government was

established by William Penn in about 1682 to become primarily a refuge

for persecuted English Quakers; but others were welcomed. Baptists,

German and Swiss Protestants and Anabaptists

also flocked to Pennsylvania. The lure of cheap land, religious freedom

and the right to improve themselves with their own hand was very

attractive.

Forced immigration and enslavement

African slaves 17th-century Virginia, 1670.

Slavery was a common practice in the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans, as different American Indian groups captured and held other tribes' members as slaves. Many of these captives were forced to undergo human sacrifice in Amerindian civilizations such as the Aztecs. In response to some enslavement of natives in the Caribbean during the early years, the Spanish Crown passed a series of laws prohibiting slavery as early as 1512. A new stricter set of laws was passed in 1542, called the New Laws of the Indies for the Good Treatment and Preservation of Indians, or simply New Laws. These were created to prevent the exploitation of the indigenous peoples by the encomenderos or landowners, by strictly limiting their power and dominion.

This helped curb Indian slavery considerably, though not completely.

Later, with the arrival of other European colonial powers in the New

World, the enslavement of native populations increased, as these empires

lacked legislation against slavery until decades later. The population

of indigenous peoples declined (mostly from European diseases, but also

from forced exploitation and atrocities). Later, native workers were

replaced by Africans imported through a large commercial slave trade.

By the 18th century, the overwhelming number of black slaves was such that Amerindian

slavery was less commonly used. Africans, who were taken aboard slave

ships to the Americas, were primarily obtained from their African

homelands by coastal tribes who captured and sold them. Europeans traded

for slaves with the slave capturers of the local native African tribes

in exchange for rum, guns, gunpowder, and other manufactures.

Slavery

Harbour Street, Kingston, Jamaica, c. 1820

The total slave trade to islands in the Caribbean, Brazil, Mexico and to the United States is estimated to have involved 12 million Africans.

The vast majority of these slaves went to sugar colonies in the

Caribbean and to Brazil, where life expectancy was short and the numbers

had to be continually replenished. At most about 600,000 African slaves

were imported into the United States, or 5% of the 12 million slaves

brought across from Africa.

Life expectancy was much higher in the United States (because of better

food, less disease, lighter work loads, and better medical care) so the

numbers grew rapidly by excesses of births over deaths, reaching 4

million by the 1860 Census. Slaves were a valuable commodity both for

work and for sale in slave markets and so the policy of actively

encouraging or forcing slaves to breed developed, especially after the

ending of the Atlantic slave trade.

From 1770 until 1860, the rate of growth of North American slaves was

much greater than for the population of any nation in Europe, and was

nearly twice as rapid as that of England.

Slaves imported to the Thirteen colonies/United States by time period:

- 1619–1700 – 21,000

- 1701–1760 – 189,000

- 1761–1770 – 63,000

- 1771–1790 – 56,000

- 1791–1800 – 79,000

- 1801–1810 – 124,000

- 1810–1865 – 51,000

- Total – 597,000

Disease and indigenous population loss

Drawing accompanying text in Book XII of the 16th-century Florentine Codex (compiled 1540–1585)

Nahua suffering from smallpox

Nahua suffering from smallpox

The European lifestyle included a long history of sharing close

quarters with domesticated animals such as cows, pigs, sheep, goats,

horses, dogs and various domesticated fowl,

from which many diseases originally stemmed. Thus, in contrast to the

indigenous people, Europeans had developed a richer endowment of

antibodies. The large-scale contact with Europeans after 1492 introduced Eurasian germs to the indigenous people of the Americas.

Epidemics of smallpox (1518, 1521, 1525, 1558, 1589), typhus (1546), influenza (1558), diphtheria (1614) and measles (1618) swept the Americas subsequent to European contact, killing between 10 million and 100 million people, up to 95% of the indigenous population of the Americas.

The cultural and political instability attending these losses appears

to have been of substantial aid in the efforts of various colonists in

New England and Massachusetts to acquire control over the great wealth

in land and resources of which indigenous societies had customarily made

use.

Such diseases yielded human mortality of an unquestionably

enormous gravity and scale – and this has profoundly confused efforts to

determine its full extent with any true precision. Estimates of the pre-Columbian population of the Americas vary tremendously.

Others have argued that significant variations in population size

over pre-Columbian history are reason to view higher-end estimates with

caution. Such estimates may reflect historical population maxima, while

indigenous populations may have been at a level somewhat below these

maxima or in a moment of decline in the period just prior to contact

with Europeans. Indigenous populations hit their ultimate lows in most

areas of the Americas in the early 20th century; in a number of cases,

growth has returned.

According to scientists from University College London, the colonization of the Americas by Europeans killed so much of the indigenous population that it resulted in climate change and global cooling.

Impact of colonial land ownership on long-term development

Geographic

differences between the colonies played a large determinant in the

types of political and economic systems that later developed. In their

paper on institutions and long-run growth, economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson

argue that certain natural endowments gave rise to distinct colonial

policies promoting either smallholder or coerced labor production.

Densely settled populations, for example, were more easily exploitable

and profitable as slave labor. In these regions, landowning elites were

economically incentivized to develop forced labor arrangements such as

the Peru mit'a system or Argentinian latifundias without regard for democratic norms. French and British colonial leaders, conversely, were incentivized to develop capitalist markets, property rights, and democratic institutions in response to natural environments that supported smallholder production over forced labor.

James Mahoney, a professor at Northwestern University, proposes that colonial policy choices made at critical junctures regarding land ownership in coffee-rich Central America fostered enduring path dependent institutions. Coffee economies in Guatemala and El Salvador,

for example, were centralized around large plantations that operated

under coercive labor systems. By the 19th century, their political

structures were largely authoritarian and militarized. In Colombia and Costa Rica, conversely, liberal reforms were enacted at critical junctures to expand commercial agriculture, and they ultimately raised the bargaining power

of the middle class. Both nations eventually developed more democratic

and egalitarian institutions than their highly concentrated landowning

counterparts.

List of European colonies in the Americas

Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic. Founded in 1502, the city is the oldest continuously-inhabited European settlement in the New World.

Cumaná, Venezuela. Founded in 1510, it is the oldest continuously-inhabited European city in the continental Americas.

English and (after 1707) British

- British America (1607–1783)

- Thirteen Colonies (1607–1783)

- Rupert's Land (1670–1870)

- British Columbia (1793–1871)

- British North America (1783–1907)

- British West Indies

- Belize

Courland (indirectly part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth)

- New Courland (Tobago) (1654–1689); Courland is now part of Latvia

Danish

- Danish West Indies (1754–1917)

- Greenland (1814–present)

Dutch

- Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, the governor of the Dutch colony of Suriname, 1923

- Suriname (1667–1954) (After independence still within the Kingdom Of The Netherlands until 1975)

- Curaçao and Dependencies (1634–1954) (Aruba and Curaçao are still in the Kingdom Of The Netherlands, Bonaire; 1634–present)

- Sint Eustatius and Dependencies (1636–1954) (Sint Maarten is still in the Kingdom Of The Netherlands, Sint Eustatius and Saba; 1636–present)

French

- New France (1604–1763)

- Acadia (1604–1713)

- Canada (1608–1763)

- Louisiana (1699–1763, 1800–1803)

- Newfoundland (1662–1713)

- Île Royale (1713–1763)

- French Guiana (1763–present)

- French West Indies

- Fort Lachine in New France, 1689

- Saint-Domingue (1659–1804, now Haiti)

- Tobago

- Virgin Islands

- France Antarctique (1555–1567)

- Equinoctial France (1612–1615)

Knights of Malta

- Saint Barthélemy (1651–1665)

- Saint Christopher (1651–1665)

- Saint Croix (1651–1665)

- Saint Martin (1651–1665)

Norwegian

- Greenland (986–1814)

- Dano-Norwegian West Indies (1754–1814)

- Sverdrup Islands (1898–1930)

- Erik the Red's Land (1931–1933)

Portuguese

- Colonial Brazil (1500–1815) became a Kingdom, United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

- Terra do Labrador (1499/1500–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Land of the Corte-Real, also known as Terra Nova dos Bacalhaus (Land of Codfish) – Terra Nova (Newfoundland) (1501–?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Portugal Cove-St. Philip's (1501–1696)

- Nova Scotia (1519?–1520s?) Claimed region (sporadically settled).

- Barbados (1536–1620)

- Colonia do Sacramento (1680–1705/1714–1762/1763–1777 (1811–1817))

- Cisplatina (1811–1822, now Uruguay)

- French Guiana (1809–1817)

Russian

The Russian-American Company's capital at New Archangel (present-day Sitka, Alaska) in 1837

- Russian America (Alaska) (1799–1867)

Scottish

- Nova Scotia (1622–1632)

- Darien Scheme on the Isthmus of Panama (1698–1700)

- Stuarts Town, Carolina (1684–1686)

Spanish

- Cuba (until 1898)

- Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717–1819)

- Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821)

- Louisiana (New Spain)

Spanish General Arsenio Martínez Campos in Havana, Spanish Cuba, 1878

- Spanish Florida (1565-1763)

- Spanish Texas (1716-1802)

- Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1824)

- Captaincy General of Chile

- Puerto Rico (1493–1898)

- Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (1776–1814)

- Hispaniola (1493–1865); the island currently comprising Haiti and the Dominican Republic, under Spanish rule in whole or in part from 1492–1865.

Swedish

- New Sweden (1638–1655)

- Saint Barthélemy (1784–1878)

- Guadeloupe (1813–1814)

Failed attempts

German

- Klein-Venedig (Holy Roman Empire)

- Hanauisch-Indien (in German)

- Saint Thomas (Brandenburg colony)

- German caribbean (German Empire)

- Ernst Thälmann Island (East Germany)

Italian

- Tuscan Guiana (now French Guiana)

Exhibitions and collections

In 2007, the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History and the Virginia Historical Society (VHS) co-organized a traveling exhibition to recount the strategic alliances and violent conflict between European empires (English, Spanish, French) and the Native people living in North America. The exhibition was presented in three languages and with multiple perspectives. Artifacts on display included rare surviving Native and European artifacts, maps, documents, and ceremonial objects from museums and royal collections on both sides of the Atlantic. The exhibition opened in Richmond, Virginia on March 17, 2007, and closed at the Smithsonian International Gallery on October 31, 2009.The related online exhibition explores the international origins of the societies of Canada and the United States and commemorates the 400th anniversary of three lasting settlements in Jamestown (1607), Québec (1608), and Santa Fe (1609). The site is accessible in three languages.