Jewish eschatology is the area of Jewish philosophy and theology concerned with events that will happen in the end of days and related concepts, according to the Hebrew Bible and Jewish thought. This includes the ingathering of the exiled diaspora, the coming of a Jewish Messiah, afterlife, and the revival of the dead Tzadikim. In Judaism, the end times are usually called the "end of days" (aḥarit ha-yamim, אחרית הימים), a phrase that appears several times in the Tanakh.

Until the late modern era, the standard Jewish belief was that after one dies, one's immortal soul joins God in the world to come

while one's body decomposes. At the end of days, God will recompose

one's body, place within it one's immortal soul, and that person will

stand before God in judgement. The idea of a messianic age has a prominent place in Jewish thought, and is incorporated as part of the end of days. Jewish philosophers from medieval times to the present day have emphasized the soul's immortality.

Origins and development

In Judaism,

the main textual source for the belief in the end of days and

accompanying events is the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. The roots of Jewish

eschatology are to be found in the pre-exile Prophets, including Isaiah

and Jeremiah, and the exile-prophets Ezekiel and Deutero-Isaiah. The main tenets of Jewish eschatology are the following, in no particular order, elaborated in the Books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel:

- End of world (before everything as follows).

- God redeems the Jewish people from the captivity that began during the Babylonian Exile, in a new Exodus

- God returns the Jewish people to the Land of Israel

- God restores the House of David and the Temple in Jerusalem

- God creates a regent from the House of David (i.e. the Jewish Messiah) to lead the Jewish people and the world and usher in an age of justice and peace

- All nations recognize that the God of Israel is the only true God

- God resurrects the dead

- God creates a new heaven and a new earth

It is also believed that history will complete itself and the

ultimate destination will be reached when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.

Jewish messianism

Etymology

The Hebrew word mashiach (or moshiach) refers to the Jewish idea of the messiah. Mashiach means anointed, a meaning preserved in the English word derived from it, messiah. The Messiah is to be a human leader, physically descended from the Davidic line, who will rule and unite the people of Israel and will usher in the Messianic Age of global and universal peace. While the name of Jewish Messiah is considered to be one of the things that precede creation, he is not considered divine, in contrast to Christianity where Jesus is both divine and the Messiah.

In biblical times the title mashiach was awarded to

someone in a high position of nobility and greatness. For example, Cohen

ha-Mašíaḥ means High Priest. In the Talmudic era the title mashiach or מלך המשיח, Méleḫ ha-Mašíaḥ (in the Tiberian vocalization

is pronounced Méleḵ haMMāšîªḥ) literally means "the anointed King". It

is a reference to the Jewish leader and king that will redeem Israel in

the end of days and usher in a messianic era of peace and prosperity for

both the living and deceased.

Early Second Temple period (516 BCE - c.220 BCE)

Early in the Second temple Period hopes for a better future are described in the Jewish scriptures.

After the return from the Babylonic exile, the Persian king Cyrus II

was called "messiah" in Isiaiah, due to his role in the return of the

Jews exiles.

Later Second Temple Period (c.220 BCE - 70 CE)

A

number of messianic ideas developed during the later Second Temple

Period, ranging from this-worldy, political expectations, to apocalyptic

expectations of an endtime in which the dead would be resurrected and

the Kingdom of Heaven would be established on earth.

The Messiah might be a kingly "Son of David," or a more heavenly "Son

of Man," but "Messianism became increasingly eschatological, and

eschatology was decisively influenced by apocalypticism," while

"messianic expectations became increasingly focused on the figure of an

individual savior.

According to Zwi Werblowsky, "the Messiah no longer symbolized the

coming of the new age, but he was somehow supposed to bring it about.

The "Lord's anointed" thus became the "savior and redeemer" and the

focus of more intense expectations and doctrines." Messianic ideas developed both by new interpretations (pesher, midrash) of the Jewish scriptures, but also by visionary revelations.

Talmud

A full set of the Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud (200-500 CE), tractate Sanhedrin, contains a long discussion of the events leading to the coming of the Messiah.

Throughout Jewish history Jews have compared these passages (and

others) to contemporary events in search of signs of the Messiah's

imminent arrival, continuing into present times.

The Talmud tells many stories about the Messiah, some of which

represent famous Talmudic rabbis as receiving personal visitations from Elijah the Prophet and the Messiah.

Rabbinic commentaries

Monument to Maimonides in Córdoba

In rabbinic literature, the rabbis elaborated and explained the prophecies that were found in the Hebrew Bible along with the oral law and rabbinic traditions about its meaning.

Maimonides' commentary to tractate Sanhedrin

stresses a relatively naturalistic interpretation of the Messiah,

de-emphasizing miraculous elements. His commentary became widely

(although not universally) accepted in the non- or less-mystical

branches of Orthodox Judaism.

Contemporary views

Orthodox Judaism

The belief in a human Messiah of the Davidic line is a universal tenet of faith among Orthodox Jews and one of Maimonides' thirteen principles of faith.

Some authorities in Orthodox Judaism believe that this era will

lead to supernatural events culminating in a bodily resurrection of the

dead. Maimonides, on the other hand, holds that the events of the messianic era are not specifically connected with the resurrection. (See the Maimonides article.)

Conservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism varies in its teachings. While it retains traditional references to a personal redeemer and prayers for the restoration of the Davidic line in the liturgy, Conservative Jews are more inclined to accept the idea of a messianic era:

We do not know when the Messiah will come, nor whether he will be a charismatic human figure or is a symbol of the redemption of mankind from the evils of the world. Through the doctrine of a Messianic figure, Judaism teaches us that every individual human being must live as if he or she, individually, has the responsibility to bring about the messianic age. Beyond that, we echo the words of Maimonides based on the prophet Habakkuk (2:3) that though he may tarry, yet do we wait for him each day... (Emet ve-Emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism)

Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism generally concurs with the more liberal Conservative perspective of a future messianic era rather than a personal Messiah.

Characteristics of the endtime

War of Gog and Magog

According to Ezekiel chapter 38, the "war of Gog and Magog", a climactic war, will take place at the end of the Jewish exile. According to Radak, this war will take place in Jerusalem.

However, a chassidic tradition holds that the war will not in fact

occur, as the sufferings of exile have already made up for it.

The world to come

Olam Ha-Ba

The hereafter is known as olam ha-ba the "world to come", עולם הבא in Hebrew, and related to concepts of Gan Eden, the Heavenly "Garden in Eden", or paradise, and Gehinom. The phrase olam ha-ba does not occur in the Hebrew Bible. The accepted halakha is that it is impossible for living human beings to know what the world to come is like.

Second Temple Period

In the late Second Temple period, beliefs about the ultimate fate of the individual were diverse. The Essenes believed in the immortality of the soul, but the Pharisees and Sadducees, apparently, did not. The Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Pseudepigrapha and Jewish magical papyri reflect this diversity.

Medieval rabbinical views

While all classic rabbinic sources discuss the afterlife, the classic Medieval scholars dispute the nature of existence in the "End of Days" after the messianic period. While Maimonides describes an entirely spiritual existence for souls, which he calls "disembodied intellects," Nahmanides

discusses an intensely spiritual existence on Earth, where spirituality

and physicality are merged. Both agree that life after death is as

Maimonides describes the "End of Days." This existence entails an

extremely heightened understanding of and connection to the Divine

Presence. This view is shared by all classic rabbinic scholars.

According to Maimonides, any non-Jew who lives according to the Seven Laws of Noah is regarded as a righteous gentile, and is assured of a place in the world to come, the final reward of the righteous.

There is much rabbinic material on what happens to the soul

of the deceased after death, what it experiences, and where it goes. At

various points in the afterlife journey, the soul may encounter: Hibbut ha-kever, the pains of the grave; Dumah, the angel of silence; Satan as the angel of death; the Kaf ha-Kela, the catapult of the soul; Gehinom (purgatory); and Gan Eden (heaven or paradise).

All classic rabbinic scholars agree that these concepts are beyond

typical human understanding. Therefore, these ideas are expressed

throughout rabbinic literature through many varied parables and

analogies.

Gehinom is fairly well defined in rabbinic literature. It is sometimes translated as "hell", but is much closer to the Catholic view of purgatory than to the Christian view of hell,

which differs from the classical Jewish view. Rabbinic thought

maintains that souls are not tortured in gehinom forever; the longest

that one can be there is said to be eleven months, with the exception of

heretics, and unobservant Jews. This is the reason that even when in mourning for near relatives, Jews will not recite mourner's kaddish for longer than an eleven-month period. Gehinom is considered a spiritual forge where the soul is purified for its eventual ascent to Gan Eden ("Garden of Eden").

19th century legends

In the 19th century book Legends of the Jews, Louis Ginzberg compiled Jewish legends found in rabbinic literature.

Among the legends are ones about the world to come and the two Gardens

of Eden. The world to come is called Paradise, and it is said to have a

double gate made of carbuncle that is guarded by 600,000 shining angels. Seven clouds of glory overshadow Paradise, and under them, in the center of Paradise, stands the tree of life. The tree of life overshadows Paradise too, and it has fifteen thousand

different tastes and aromas that winds blow all across Paradise.

Under the tree of life are many pairs of canopies, one of stars and the

other of sun and moon, while a cloud of glory separates the two. In

each pair of canopies sits a rabbinic scholar who explains the Torah to

one. When one enters Paradise one is proffered by Michael (archangel) to God on the altar of the temple of the heavenly Jerusalem,

whereupon one is transfigured into an angel (the ugliest person

becomes as beautiful and shining as "the grains of a silver pomegranate

upon which fall the rays of the sun"). The angels that guard Paradise's gate adorn one in seven clouds of glory, crown one with gems and pearls and gold, place eight myrtles

in one's hand, and praise one for being righteous while leading one to a

garden of eight hundred roses and myrtles that is watered by many

rivers. In the garden is one's canopy, its beauty according to one's merit, but each canopy has four rivers - milk, honey, wine, and balsam - flowing out from it, and has a golden vine and thirty shining pearls hanging from it. Under each canopy is a table of gems and pearls attended to by sixty angels. The light of Paradise is the light of the righteous people therein.

Each day in Paradise one wakes up a child and goes to bed an elder to

enjoy the pleasures of childhood, youth, adulthood, and old age. In each corner of Paradise is a forest of 800,000 trees, the least among the trees greater than the best herbs and spices, attended to by 800,000 sweetly singing angels. Paradise is divided into seven paradises, each one 120,000 miles long and wide.

Depending on one's merit, one joins one of the paradises: the first is

made of glass and cedar and is for converts to Judaism; the second is

of silver and cedar and is for penitents; the third is of silver and

gold, gems and pearls, and is for the patriarchs, Moses and Aaron, the

Israelites that left Egypt and lived in the wilderness, and the kings of

Israel; the fourth is of rubies and olive wood and is for the holy and

steadfast in faith; the fifth is like the third, except a river flows

through it and its bed was woven by Eve and angels, and it is for the

Messiah and Elijah; and the sixth and seventh divisions are not

described, except that they are respectively for those who died doing a

pious act and for those who died from an illness in expiation for

Israel's sins.

Beyond Paradise, according to Legends of the Jews, is the higher

Gan Eden, where God is enthroned and explains the Torah to its

inhabitants. The higher Gan Eden contains three hundred ten worlds and is divided into seven compartments.

The compartments are not described, though it is implied that each

compartment is greater than the previous one and is joined based on

one's merit. The first compartment is for Jewish martyrs, the second for those who drowned, the third for "Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai

and his disciples," the fourth for those whom the cloud of glory

carried off, the fifth for penitents, the sixth for youths who have

never sinned; and the seventh for the poor who lived decently and

studied the Torah.

In contemporary Judaism

Irving Greenberg

Irving Greenberg, representing a Modern Orthodox

viewpoint, describes the afterlife as a central Jewish teaching,

deriving from the belief in reward and punishment. According to

Greenberg, suffering Medieval

Jews emphasized the World to Come as a counterpoint to the difficulties

of this life, while early Jewish modernizers portrayed Judaism as

interested only in this world as a counterpoint to "otherworldly"

Christianity. Greenberg sees each of these views as leading to an

undesired extreme - overemphasizing the afterlife leads to asceticism,

while devaluing the afterlife deprives Jews of the consolation of

eternal life and justice - and calls for a synthesis, in which Jews can

work to perfect this world, while also recognizing the immortality of

the soul.

Conservative Judaism both affirms belief in the world beyond (as referenced in the Amidah

and Maimonides' Thirteen Precepts of Faith) while recognizing that

human understanding is limited and we cannot know exactly what the world

beyond consists of. Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism affirm belief

in the afterlife, though they downplay the theological implications in

favor of emphasizing the importance of the "here and now," as opposed to

reward and punishment.

Resurrection of the dead

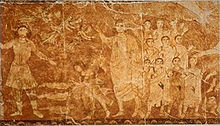

Resurrection of the dead, fresco from the Dura-Europos synagogue

Several times, the Bible alludes to eternal life without specifying what form that life will take.

The first explicit mention of resurrection is the Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones in the Book of Ezekiel.

However, this narrative was intended as a metaphor for national

rebirth, promising the Jews return to Israel and reconstruction of the Temple, not as a description of personal resurrection.

The Book of Daniel promised literal resurrection to the Jews, in concrete detail. Daniel wrote that with the coming of the Archangel Michael, misery would beset the world, and only those whose names were in a divine book would be resurrected.

Moreover, Daniel's promise of resurrection was intended only for the

most righteous and the most sinful because the afterlife was a place for

the virtuous individuals to be rewarded and the sinful individuals to

receive eternal punishment.

Greek and Persian culture influenced Jewish sects to believe in an afterlife between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE as well.

The Hebrew Bible, at least as seen through interpretation of Bavli Sanhedrin, contains frequent reference to resurrection of the dead. The Mishnah (c. 200) lists belief in the resurrection of the dead as one of three essential beliefs necessary for a Jew to participate in it:

All Israel have a portion in the world to come, for it is written: 'Thy people are all righteous; they shall inherit the land forever, the branch of my planting, the work of my hands, that I may be glorified.' But the following have no portion therein: one who maintains that resurrection is not a biblical doctrine, the Torah was not divinely revealed, and an Apikoros ('heretic').

In the late Second Temple period, the Pharisees believed in resurrection, while Essenes and Sadducees did not. During the Rabbinic period,

beginning in the late first century and carrying on to the present, the

works of Daniel were included into the Hebrew Bible, signaling the

adoption of Jewish resurrection into the officially sacred texts.

Jewish liturgy, most notably the Amidah, contains references to the tenet of the bodily resurrection of the dead. In contemporary Judaism, both Orthodox Judaism and Conservative Judaism maintain the traditional references to it in their liturgy. However, many Conservative Jews interpret the tenet metaphorically rather than literally.

Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism have altered traditional

references to the resurrection of the dead in the liturgy ("who gives

life to the dead") to refer to "who gives life to all."

The last judgment

In Judaism, the day of judgment happens every year on Rosh Hashanah;

therefore, the belief in a last day of judgment for all mankind is

disputed. Some rabbis hold that there will be such a day following the

resurrection of the dead. Others hold that there is no need for that

because of Rosh Hashanah. Yet others hold that this accounting and

judgment happens when one dies. Other rabbis hold that the last judgment

only applies to the gentile nations and not the Jewish people.