Aesthetics, or esthetics (/ɛsˈθɛtɪks,

In its more technical epistemological perspective, it is defined as the study of subjective and sensori-emotional values, or sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste. Aesthetics studies how artists imagine, create and perform works of art; how people use, enjoy, and criticize art; and what happens in their minds when they look at paintings, listen to music, or read poetry, and understand what they see and hear. It also studies how they feel about art — why they like some works and not others, and how art can affect their moods, beliefs, and attitude toward life. The phrase was coined in English in the 18th century.

More broadly, scholars in the field define aesthetics as "critical reflection on art, culture and nature". In modern English, the term aesthetic can also refer to a set of principles underlying the works of a particular art movement or theory: one speaks, for example, of the Cubist aesthetic.

Etymology

The word aesthetic is derived from the Greek αἰσθητικός (aisthetikos, meaning "esthetic, sensitive, sentient, pertaining to sense perception"), which in turn was derived from αἰσθάνομαι (aisthanomai, meaning "I perceive, feel, sense" and related to αἴσθησις (aisthēsis, "sensation").

Aesthetics in this central sense has been said to start with the series

of articles on “The Pleasures of the Imagination” which the journalist

Joseph Addison wrote in the early issues of the magazine The Spectator in 1712. The term "aesthetics" was appropriated and coined with new meaning by the German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten in his dissertation Meditationes philosophicae de nonnullis ad poema pertinentibus ("Philosophical considerations of some matters pertaining the poem") in 1735;

Baumgarten chose "aesthetics" because he wished to emphasize the

experience of art as a means of knowing. Aesthetics, a not very tidy

intellectual discipline, is a heterogeneous collection of problems that

concern the arts primarily but also relate to nature. even though his later definition in the fragment Aesthetica (1750) is more often referred to as the first definition of modern aesthetics.

Aesthetics and the philosophy of art

Aesthetics is for the artist as Ornithology is for the birds.

Some separate aesthetics and philosophy of art, claiming that the

former is the study of beauty while the latter is the study of works of

art. However, most commonly Aesthetics encompasses both questions around

beauty as well as questions about art. It examines topics such as

aesthetic objects, aesthetic experience, and aesthetic judgments. For some, aesthetics is considered a synonym for the philosophy of art since Hegel,

while others insist that there is a significant distinction between

these closely related fields. In practice, aesthetic judgement refers to

the sensory contemplation or appreciation of an object (not necessarily

an art object), while artistic judgement refers to the recognition, appreciation or criticism of art or an art work.

Philosophical aesthetics has not only to speak about art and to produce judgments about art works, but also has to give a definition of what art is. Art is an autonomous entity for philosophy, because art deals with the senses

(i.e. the etymology of aesthetics) and art is as such free of any moral

or political purpose. Hence, there are two different conceptions of art

in aesthetics: art as knowledge or art as action, but aesthetics is neither epistemology nor ethics.

Aestheticians compare historical developments with theoretical

approaches to the arts of many periods. They study the varieties of art

in relation to their physical, social, and culture environments.

Aestheticians also use psychology to understand how people see, hear,

imagine, think, learn, and act in relation to the materials and problems

of art. Aesthetic psychology studies the creative process and the

aesthetic experience.

Aesthetic judgment, universals and ethics

Aesthetic judgment

Aesthetics examines our affective domain

response to an object or phenomenon. Judgments of aesthetic value rely

on our ability to discriminate at a sensory level. However, aesthetic judgments usually go beyond sensory discrimination.

For David Hume,

delicacy of taste is not merely "the ability to detect all the

ingredients in a composition", but also our sensitivity "to pains as

well as pleasures, which escape the rest of mankind." Thus, the sensory discrimination is linked to capacity for pleasure.

For Immanuel Kant (Critique of Judgment, 1790), "enjoyment" is the result when pleasure arises from sensation, but judging something

to be "beautiful" has a third requirement: sensation must give rise to

pleasure by engaging our capacities of reflective contemplation.

Judgments of beauty are sensory, emotional and intellectual all at once.

Kant (1790) observed of a man "If he says that canary wine is agreeable

he is quite content if someone else corrects his terms and reminds him

to say instead: It is agreeable to me," because "Everyone has his own (sense of) taste".

The case of "beauty" is different from mere "agreeableness" because,

"If he proclaims something to be beautiful, then he requires the same

liking from others; he then judges not just for himself but for

everyone, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things." Roger Scruton has argued similarly.

Viewer interpretations of beauty may on occasion be observed to

possess two concepts of value: aesthetics and taste. Aesthetics is the

philosophical notion of beauty. Taste is a result of an education

process and awareness of elite cultural values learned through exposure

to mass culture.

Bourdieu examined how the elite in society define the aesthetic values

like taste and how varying levels of exposure to these values can result

in variations by class, cultural background, and education. According to Kant, beauty is subjective and universal; thus certain things are beautiful to everyone. In the opinion of Władysław Tatarkiewicz,

there are six conditions for the presentation of art: beauty, form,

representation, reproduction of reality, artistic expression and

innovation. However, one may not be able to pin down these qualities in a

work of art.

Factors involved in aesthetic judgment

Rainbows often have aesthetic appeal.

Judgments of aesthetical values seem often to involve many other

kinds of issues as well. Responses such as disgust show that sensory

detection is linked in instinctual ways to facial expressions, and even behaviours like the gag reflex.

Yet disgust can often be a learned or cultural issue too; as Darwin

pointed out, seeing a stripe of soup in a man's beard is disgusting even

though neither soup nor beards

are themselves disgusting. Aesthetic judgments may be linked to

emotions or, like emotions, partially embodied in our physical

reactions. For example, the awe inspired by a sublime

landscape might physically manifest with an increased heart-rate or

pupil dilation; physiological reaction may express or even cause the

initial awe.

As seen, emotions are conformed to 'cultural' reactions,

therefore aesthetics is always characterized by 'regional responses', as

Francis Grose was the first to affirm in his ‘Rules for Drawing

Caricaturas: With an Essay on Comic Painting’ (1788), published in W.

Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, Bagster, London s.d. (1791? [1753]),

pp. 1–24. Francis Grose can therefore be claimed to be the first

critical 'aesthetic regionalist' in proclaiming the anti-universality of

aesthetics in contrast to the perilous and always resurgent

dictatorship of beauty.

'Aesthetic Regionalism' can thus be seen as a political statement and

stance which vies against any universal notion of beauty to safeguard

the counter-tradition of aesthetics related to what has usually been

considered and dubbed un-beautiful just because one's culture does not

contemplate it, e.g. E. Burke's sublime, what is usually defined as

'primitive' art, or un-harmonious, non-cathartic art, camp art, which

'beauty' posits and creates, dichotomously, as its opposite, without

even the need of formal statements, but which will be 'perceived' as

ugly.

Likewise, aesthetic judgments may be culturally conditioned to some extent. Victorians in Britain often saw African sculpture as ugly, but just a few decades later, Edwardian

audiences saw the same sculptures as being beautiful. Evaluations of

beauty may well be linked to desirability, perhaps even to sexual desirability. Thus, judgments of aesthetic value can become linked to judgments of economic, political, or moral value. In a current context, one might judge a Lamborghini

to be beautiful partly because it is desirable as a status symbol, or

we might judge it to be repulsive partly because it signifies for us

over-consumption and offends our political or moral values.

Aesthetic judgments can often be very fine-grained and internally

contradictory. Likewise aesthetic judgments seem often to be at least

partly intellectual and interpretative. It is what a thing means or

symbolizes for us that is often what we are judging. Modern

aestheticians have asserted that will and desire were almost dormant in aesthetic experience, yet preference and choice have seemed important aesthetics to some 20th-century thinkers. The point is already made by Hume, but see Mary Mothersill, "Beauty and the Critic's Judgment", in The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics,

2004. Thus aesthetic judgments might be seen to be based on the senses,

emotions, intellectual opinions, will, desires, culture, preferences,

values, subconscious behaviour, conscious decision, training, instinct,

sociological institutions, or some complex combination of these,

depending on exactly which theory one employs.

A third major topic in the study of aesthetic judgments is how

they are unified across art forms. For instance, the source of a

painting's beauty has a different character to that of beautiful music,

suggesting their aesthetics differ in kind. The distinct inability of language to express aesthetic judgment and the role of Social construction further cloud this issue.

Aesthetic universals

The philosopher Denis Dutton identified six universal signatures in human aesthetics:

- Expertise or virtuosity. Humans cultivate, recognize, and admire technical artistic skills.

- Nonutilitarian pleasure. People enjoy art for art's sake, and do not demand that it keep them warm or put food on the table.

- Style. Artistic objects and performances satisfy rules of composition that place them in a recognizable style.

- Criticism. People make a point of judging, appreciating, and interpreting works of art.

- Imitation. With a few important exceptions like abstract painting, works of art simulate experiences of the world.

- Special focus. Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience.

Artists such as Thomas Hirschhorn

have indicated that there are too many exceptions to Dutton's

categories. For example, Hirschhorn's installations deliberately eschew

technical virtuosity. People can appreciate a Renaissance Madonna

for aesthetic reasons, but such objects often had (and sometimes still

have) specific devotional functions. "Rules of composition" that might

be read into Duchamp's Fountain or John Cage's 4′33″

do not locate the works in a recognizable style (or certainly not a

style recognizable at the time of the works' realization). Moreover,

some of Dutton's categories seem too broad: a physicist might entertain

hypothetical worlds in his/her imagination in the course of formulating a

theory. Another problem is that Dutton's categories seek to

universalize traditional European notions of aesthetics and art

forgetting that, as André Malraux and others have pointed out, there

have been large numbers of cultures in which such ideas (including the

idea "art" itself) were non-existent.

Aesthetic ethics

Aesthetic

ethics refers to the idea that human conduct and behaviour ought to be

governed by that which is beautiful and attractive. John Dewey

has pointed out that the unity of aesthetics and ethics is in fact

reflected in our understanding of behaviour being "fair"—the word having

a double meaning of attractive and morally acceptable. More recently, James Page has suggested that aesthetic ethics might be taken to form a philosophical rationale for peace education.

New Criticism and "The Intentional Fallacy"

During

the first half of the twentieth century, a significant shift to general

aesthetic theory took place which attempted to apply aesthetic theory

between various forms of art, including the literary arts and the visual

arts, to each other. This resulted in the rise of the New Criticism school and debate concerning the intentional fallacy.

At issue was the question of whether the aesthetic intentions of the

artist in creating the work of art, whatever its specific form, should

be associated with the criticism and evaluation of the final product of

the work of art, or, if the work of art should be evaluated on its own

merits independent of the intentions of the artist.

In 1946, William K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley published a classic and controversial New Critical essay entitled "The Intentional Fallacy", in which they argued strongly against the relevance of an author's intention,

or "intended meaning" in the analysis of a literary work. For Wimsatt

and Beardsley, the words on the page were all that mattered; importation

of meanings from outside the text was considered irrelevant, and

potentially distracting.

In another essay, "The Affective Fallacy,"

which served as a kind of sister essay to "The Intentional Fallacy"

Wimsatt and Beardsley also discounted the reader's personal/emotional

reaction to a literary work as a valid means of analyzing a text. This

fallacy would later be repudiated by theorists from the reader-response school of literary theory. One of the leading theorists from this school, Stanley Fish, was himself trained by New Critics. Fish criticizes Wimsatt and Beardsley in his essay "Literature in the Reader" (1970).

As summarized by Berys Gaut

and Livingston in their essay "The Creation of Art": "Structuralist and

post-structuralists theorists and critics were sharply critical of many

aspects of New Criticism, beginning with the emphasis on aesthetic

appreciation and the so-called autonomy of art, but they reiterated the

attack on biographical criticisms' assumption that the artist's

activities and experience were a privileged critical topic."

These authors contend that: "Anti-intentionalists, such as formalists,

hold that the intentions involved in the making of art are irrelevant or

peripheral to correctly interpreting art. So details of the act of

creating a work, though possibly of interest in themselves, have no

bearing on the correct interpretation of the work."

Gaut and Livingston define the intentionalists as distinct from formalists

stating that: "Intentionalists, unlike formalists, hold that reference

to intentions is essential in fixing the correct interpretation of

works." They quote Richard Wollheim

as stating that, "The task of criticism is the reconstruction of the

creative process, where the creative process must in turn be thought of

as something not stopping short of, but terminating on, the work of art

itself."

Derivative forms of aesthetics

A

large number of derivative forms of aesthetics have developed as

contemporary and transitory forms of inquiry associated with the field

of aesthetics which include the post-modern, psychoanalytic, scientific,

and mathematical among others.

Post-modern aesthetics and psychoanalysis

Example of the Dada aesthetic, Marcel Duchamp's Fountain 1917

Early-twentieth-century artists, poets and composers challenged

existing notions of beauty, broadening the scope of art and aesthetics.

In 1941, Eli Siegel, American philosopher and poet, founded Aesthetic Realism,

the philosophy that reality itself is aesthetic, and that "The world,

art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of

opposites."

Various attempts have been made to define Post-Modern

Aesthetics. The challenge to the assumption that beauty was central to

art and aesthetics, thought to be original, is actually continuous with

older aesthetic theory; Aristotle was the first in the Western tradition

to classify "beauty" into types as in his theory of drama, and Kant

made a distinction between beauty and the sublime. What was new was a

refusal to credit the higher status of certain types, where the taxonomy

implied a preference for tragedy and the sublime to comedy and the Rococo.

Croce suggested that "expression" is central in the way that beauty was once thought to be central. George Dickie suggested that the sociological institutions of the art world were the glue binding art and sensibility into unities. Marshall McLuhan

suggested that art always functions as a "counter-environment" designed

to make visible what is usually invisible about a society. Theodor Adorno

felt that aesthetics could not proceed without confronting the role of

the culture industry in the commodification of art and aesthetic

experience. Hal Foster attempted to portray the reaction against beauty and Modernist art in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Arthur Danto has described this reaction as "kalliphobia" (after the Greek word for beauty, κάλλος kallos). André Malraux

explains that the notion of beauty was connected to a particular

conception of art that arose with the Renaissance and was still dominant

in the eighteenth century (but was supplanted later). The discipline of

aesthetics, which originated in the eighteenth century, mistook this

transient state of affairs for a revelation of the permanent nature of

art. Brian Massumi suggests to reconsider beauty following the aesthetical thought in the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari.

Walter Benjamin echoed Malraux in believing aesthetics was a

comparatively recent invention, a view proven wrong in the late 1970s,

when Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake analyzed links between beauty,

information processing, and information theory. Denis Dutton in "The Art Instinct" also proposed that an aesthetic sense was a vital evolutionary factor.

Jean-François Lyotard re-invokes the Kantian distinction between taste and the sublime. Sublime painting, unlike kitsch realism, "... will enable us to see only by making it impossible to see; it will please only by causing pain."

Sigmund Freud inaugurated aesthetical thinking in Psychoanalysis mainly via the "Uncanny" as aesthetical affect. Following Freud and Merleau-Ponty, Jacques Lacan theorized aesthetics in terms of sublimation and the Thing.

The relation of Marxist aesthetics to post-modern aesthetics is still a contentious area of debate.

Recent aesthetics

Guy Sircello has pioneered efforts in analytic philosophy to develop a rigorous theory of aesthetics, focusing on the concepts of beauty, love and sublimity. In contrast to romantic theorists Sircello argued for the objectivity of beauty and formulated a theory of love on that basis.

British philosopher and theorist of conceptual art aesthetics, Peter Osborne, makes the point that "'post-conceptual art' aesthetic does not concern a particular type of contemporary art so much as the historical-ontological condition for the production of contemporary art in general ...". Osborne noted that contemporary art is 'post-conceptual' in a public lecture delivered in 2010.

Gary Tedman has put forward a theory of a subjectless aesthetics derived from Karl Marx's concept of alienation, and Louis Althusser's antihumanism, using elements of Freud's group psychology, defining a concept of the 'aesthetic level of practice'.

Gregory Loewen

has suggested that the subject is key in the interaction with the

aesthetic object. The work of art serves as a vehicle for the projection

of the individual's identity into the world of objects, as well as

being the irruptive source of much of what is uncanny in modern life. As

well, art is used to memorialize individuated biographies in a manner

that allows persons to imagine that they are part of something greater

than themselves.

Aesthetics and science

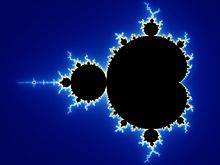

The Mandelbrot set with continuously coloured environment

The field of experimental aesthetics was founded by Gustav Theodor Fechner in the 19th century. Experimental aesthetics in these times had been characterized by a subject-based, inductive approach. The analysis of individual experience and behaviour based on experimental methods is a central part of experimental aesthetics. In particular, the perception of works of art, music, or modern items such as websites or other IT products is studied. Experimental aesthetics is strongly oriented towards the natural sciences. Modern approaches mostly come from the fields of cognitive psychology or neuroscience (neuroaesthetics).

In the 1970s, Abraham Moles and Frieder Nake were among the first to analyze links between aesthetics, information processing, and information theory.

In the 1990s, Jürgen Schmidhuber described an algorithmic theory of beauty which takes the subjectivity

of the observer into account and postulates: among several observations

classified as comparable by a given subjective observer, the

aesthetically most pleasing one is the one with the shortest

description, given the observer's previous knowledge and his particular

method for encoding the data. This is closely related to the principles of algorithmic information theory and minimum description length. One of his examples: mathematicians enjoy simple proofs with a short description in their formal language. Another very concrete example describes an aesthetically pleasing human face whose proportions can be described by very few bits of information, drawing inspiration from less detailed 15th century proportion studies by Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer. Schmidhuber's theory explicitly distinguishes between what's beautiful and what's interesting, stating that interestingness corresponds to the first derivative of subjectively perceived beauty. Here the premise is that any observer continually tries to improve the predictability and compressibility of the observations by discovering regularities such as repetitions and symmetries and fractal self-similarity. Whenever the observer's learning process (which may be a predictive artificial neural network; see also Neuroesthetics) leads to improved data compression such that the observation sequence can be described by fewer bits than before, the temporary interestingness

of the data corresponds to the number of saved bits. This compression

progress is proportional to the observer's internal reward, also called

curiosity reward. A reinforcement learning algorithm is used to maximize future expected reward by learning to execute action sequences that cause additional interesting

input data with yet unknown but learnable predictability or regularity.

The principles can be implemented on artificial agents which then

exhibit a form of artificial curiosity.

Truth in beauty and mathematics

Mathematical considerations, such as symmetry and complexity, are used for analysis in theoretical aesthetics. This is different from the aesthetic considerations of applied aesthetics used in the study of mathematical beauty. Aesthetic considerations such as symmetry and simplicity are used in areas of philosophy, such as ethics and theoretical physics and cosmology to define truth, outside of empirical considerations. Beauty and Truth have been argued to be nearly synonymous, as reflected in the statement "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" in the poem Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats,

or by the Hindu motto "Satyam Shivam Sundaram" (Satya (Truth) is Shiva

(God), and Shiva is Sundaram (Beautiful)). The fact that judgments of

beauty and judgments of truth both are influenced by processing fluency,

which is the ease with which information can be processed, has been

presented as an explanation for why beauty is sometimes equated with

truth. Indeed, recent research found that people use beauty as an indication for truth in mathematical pattern tasks. However, scientists including the mathematician David Orrell and physicist Marcelo Gleiser have argued that the emphasis on aesthetic criteria such as symmetry is equally capable of leading scientists astray.

Computational approaches

In 1928, the mathematician George David Birkhoff created an aesthetic measure M = O/C as the ratio of order to complexity.

Since about 2005, computer scientists have attempted to develop automated methods to infer aesthetic quality of images. Typically, these approaches follow a machine learning

approach, where large numbers of manually rated photographs are used to

"teach" a computer about what visual properties are of relevance to

aesthetic quality. The Acquine engine, developed at Penn State University, rates natural photographs uploaded by users.

There have also been relatively successful attempts with regard to chess and music. A relation between Max Bense's

mathematical formulation of aesthetics in terms of "redundancy" and

"complexity" and theories of musical anticipation was offered using the

notion of Information Rate.

Evolutionary aesthetics

Evolutionary aesthetics refers to evolutionary psychology theories in which the basic aesthetic preferences of Homo sapiens are argued to have evolved in order to enhance survival and reproductive success. One example being that humans are argued to find beautiful and prefer landscapes which were good habitats in the ancestral environment. Another example is that body symmetry and proportion are important aspects of physical attractiveness

which may be due to this indicating good health during body growth.

Evolutionary explanations for aesthetical preferences are important

parts of evolutionary musicology, Darwinian literary studies, and the study of the evolution of emotion.

Applied aesthetics

As well as being applied to art, aesthetics can also be applied to

cultural objects, such as crosses or tools. For example, aesthetic

coupling between art-objects and medical topics was made by speakers

working for the US Information Agency

Art slides were linked to slides of pharmacological data, which

improved attention and retention by simultaneous activation of intuitive

right brain with rational left. It can also be used in topics as

diverse as mathematics, gastronomy, fashion and website design.

Criticism

The philosophy of aesthetics as a practice has been criticized by some sociologists and writers of art and society. Raymond Williams,

for example, argues that there is no unique and or individual aesthetic

object which can be extrapolated from the art world, but rather that

there is a continuum of cultural forms and experience of which ordinary

speech and experiences may signal as art. By "art" we may frame several

artistic "works" or "creations" as so though this reference remains

within the institution or special event which creates it and this leaves

some works or other possible "art" outside of the frame work, or other

interpretations such as other phenomenon which may not be considered as

"art".

Pierre Bourdieu

disagrees with Kant's idea of the "aesthetic". He argues that Kant's

"aesthetic" merely represents an experience that is the product of an

elevated class habitus and scholarly leisure as opposed to other

possible and equally valid "aesthetic" experiences which lay outside

Kant's narrow definition.

Timothy Laurie argues that theories of musical aesthetics "framed

entirely in terms of appreciation, contemplation or reflection risk

idealizing an implausibly unmotivated listener defined solely through

musical objects, rather than seeing them as a person for whom complex

intentions and motivations produce variable attractions to cultural

objects and practices".