| Anthrax | |

|---|---|

| |

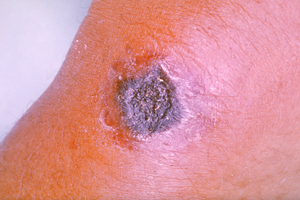

| A skin lesion caused by anthrax; the characteristic black eschar | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Skin form: small blister with surrounding swelling Inhalational form: fever, chest pain, shortness of breath Intestinal form: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain Injection form: fever, abscess |

| Usual onset | 1 day to 2 months post contact |

| Causes | Bacillus anthracis |

| Risk factors | Working with animals, travelers, postal workers, military personnel |

| Diagnostic method | Based on antibodies or toxin in the blood, microbial culture |

| Prevention | Anthrax vaccination, antibiotics |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, antitoxin |

| Prognosis | 20–80% die without treatment |

| Frequency | >2,000 cases per year |

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptoms begin between one day and two months after the infection is contracted. The skin form presents with a small blister with surrounding swelling that often turns into a painless ulcer with a black center. The inhalation form presents with fever, chest pain, and shortness of breath. The intestinal form presents with diarrhea which may contain blood, abdominal pains, and nausea and vomiting. The injection form presents with fever and an abscess at the site of drug injection.

Anthrax is spread by contact with the bacterium's spores, which often appear in infectious animal products. Contact is by breathing, eating, or through an area of broken skin. It does not typically spread directly between people. Risk factors include people who work with animals or animal products, travelers, postal workers, and military personnel. Diagnosis can be confirmed based on finding antibodies or the toxin in the blood or by culture of a sample from the infected site.

Anthrax vaccination is recommended for people who are at high risk of infection. Immunizing animals against anthrax is recommended in areas where previous infections have occurred. Two months of antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and doxycycline after exposure can also prevent infection. If infection occurs treatment is with antibiotics and possibly antitoxin. The type and number of antibiotics used depends on the type of infection. Antitoxin is recommended for those with widespread infection.

Although a rare disease, human anthrax, when it does occur, is most common in Africa and central and southern Asia. It also occurs more regularly in Southern Europe than elsewhere on the continent, and is uncommon in Northern Europe and North America. Globally, at least 2,000 cases occur a year with about two cases a year in the United States. Skin infections represent more than 95% of cases. Without treatment, the risk of death from skin anthrax is 24%. For intestinal infection, the risk of death is 25 to 75%, while respiratory anthrax has a mortality of 50 to 80%, even with treatment. Until the 20th century, anthrax infections killed hundreds of thousands of people and animals each year. Anthrax has been developed as a weapon by a number of countries. In plant-eating animals, infection occurs when they eat or breathe in the spores while grazing. Carnivores may become infected by eating infected animals.

Signs and symptoms

Skin

Skin lesion from anthrax

Skin anthrax lesion on the neck

Cutaneous anthrax, also known as hide-porter's disease, is when

anthrax occurs on the skin. It is the most common form (>90% of

anthrax cases). It is also the least dangerous form (low mortality with

treatment, 20% mortality without). Cutaneous anthrax presents as a boil-like skin lesion that eventually forms an ulcer with a black center (eschar). The black eschar often shows up as a large, painless, necrotic

ulcer (beginning as an irritating and itchy skin lesion or blister that

is dark and usually concentrated as a black dot, somewhat resembling

bread mold) at the site of infection. In general, cutaneous infections

form within the site of spore penetration between two and five days

after exposure. Unlike bruises

or most other lesions, cutaneous anthrax infections normally do not

cause pain. Nearby lymph nodes may become infected, reddened, swollen,

and painful. A scab forms over the lesion soon, and falls off in a few

weeks. Complete recovery may take longer.

Cutaneous anthrax is typically caused when B. anthracis spores

enter through cuts on the skin. This form is found most commonly when

humans handle infected animals and/or animal products.

Cutaneous anthrax is rarely fatal if treated, because the infection area is limited to the skin, preventing the lethal factor, edema factor, and protective antigen from entering and destroying a vital organ. Without treatment, about 20% of cutaneous skin infection cases progress to toxemia and death.

Lungs

Respiratory infection in humans is relatively rare and presents as two stages. It infects the lymph nodes in the chest first, rather than the lungs themselves, a condition called hemorrhagic mediastinitis,

causing bloody fluid to accumulate in the chest cavity, therefore

causing shortness of breath. The first stage causes cold and flu-like

symptoms. Symptoms include fever, shortness of breath, cough, fatigue,

and chills. This can last hours to days. Often, many fatalities from

inhalational anthrax are when the first stage is mistaken for the cold

or flu and the victim does not seek treatment until the second stage,

which is 90% fatal. The second (pneumonia) stage occurs when the

infection spreads from the lymph nodes to the lungs. Symptoms of the

second stage develop suddenly after hours or days of the first stage.

Symptoms include high fever, extreme shortness of breath, shock, and

rapid death within 48 hours in fatal cases. Historical mortality rates

were over 85%, but when treated early, observed case fatality rate dropped to 45%.

Distinguishing pulmonary anthrax from more common causes of respiratory

illness is essential to avoiding delays in diagnosis and thereby

improving outcomes. An algorithm for this purpose has been developed.

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal

(GI) infection is most often caused by consuming anthrax-infected meat

and is characterized by diarrhea, potentially with blood, abdominal

pains, acute inflammation of the intestinal tract, and loss of appetite. Occasional vomiting of blood

can occur. Lesions have been found in the intestines and in the mouth

and throat. After the bacterium invades the gastrointestinal system, it

spreads to the bloodstream and throughout the body, while continuing to

make toxins. GI infections can be treated, but usually result in

fatality rates of 25% to 60%, depending upon how soon treatment

commences. This form of anthrax is the rarest.

Cause

Bacteria

Photomicrograph of a Gram stain of the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, the cause of the anthrax disease

Bacillus anthracis is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacterium about 1 by 9 μm in size. It was shown to cause disease by Robert Koch in 1876 when he took a blood sample from an infected cow, isolated the bacteria, and put them into a mouse.

The bacterium normally rests in spore form in the soil, and can survive

for decades in this state. Herbivores are often infected whilst

grazing, especially when eating rough, irritant, or spiky vegetation;

the vegetation has been hypothesized to cause wounds within the GI

tract, permitting entry of the bacterial spores into the tissues, though

this has not been proven. Once ingested or placed in an open wound, the

bacteria begin multiplying inside the animal or human and typically

kill the host within a few days or weeks. The spores germinate at the

site of entry into the tissues and then spread by the circulation to the

lymphatics, where the bacteria multiply.

The production of two powerful exotoxins and lethal toxin by the

bacteria causes death. Veterinarians can often tell a possible

anthrax-induced death by its sudden occurrence, and by the dark,

nonclotting blood that oozes from the body orifices. Most anthrax

bacteria inside the body after death are outcompeted and destroyed by

anaerobic bacteria within minutes to hours post mortem. However,

anthrax vegetative bacteria that escape the body via oozing blood or

through the opening of the carcass may form hardy spores. These

vegetative bacteria are not contagious.

One spore forms per one vegetative bacterium. The triggers for spore

formation are not yet known, though oxygen tension and lack of nutrients

may play roles. Once formed, these spores are very hard to eradicate.

The infection of herbivores (and occasionally humans) by the

inhalational route normally proceeds as: Once the spores are inhaled,

they are transported through the air passages into the tiny air sacs

(alveoli) in the lungs. The spores are then picked up by scavenger cells

(macrophages) in the lungs and are transported through small vessels (lymphatics) to the lymph nodes in the central chest cavity (mediastinum).

Damage caused by the anthrax spores and bacilli to the central chest

cavity can cause chest pain and difficulty in breathing. Once in the

lymph nodes, the spores germinate into active bacilli that multiply and

eventually burst the macrophages, releasing many more bacilli into the

bloodstream to be transferred to the entire body. Once in the blood

stream, these bacilli release three proteins named lethal factor,

edema factor, and protective antigen. The three are not toxic by

themselves, but their combination is incredibly lethal to humans.

Protective antigen combines with these other two factors to form lethal

toxin and edema toxin, respectively. These toxins are the primary

agents of tissue destruction, bleeding, and death of the host. If

antibiotics are administered too late, even if the antibiotics eradicate

the bacteria, some hosts still die of toxemia because the toxins

produced by the bacilli remain in their systems at lethal dose levels.

- Color-enhanced scanning electron micrograph shows splenic tissue from a monkey with inhalational anthrax; featured are rod-shaped bacilli (yellow) and an erythrocyte (red)

- Gram-positive anthrax bacteria (purple rods) in cerebrospinal fluid: If present, a Gram-negative bacterial species would appear pink. (The other cells are white blood cells.)

Exposure

The spores of anthrax are able to survive in harsh conditions for decades or even centuries. Such spores can be found on all continents, including Antarctica. Disturbed grave sites of infected animals have been known to cause infection after 70 years.

Occupational exposure to infected animals or their products (such

as skin, wool, and meat) is the usual pathway of exposure for humans.

Workers who are exposed to dead animals and animal products are at the

highest risk, especially in countries where anthrax is more common.

Anthrax in livestock

grazing on open range where they mix with wild animals still

occasionally occurs in the United States and elsewhere. Many workers who

deal with wool and animal hides are routinely exposed to low levels of

anthrax spores, but most exposure levels are not sufficient to develop

anthrax infections. A lethal infection is reported to result from

inhalation of about 10,000–20,000 spores, though this dose varies among

host species. Little documented evidence is available to verify the exact or average number of spores needed for infection.

Historically, inhalational anthrax was called woolsorters' disease because it was an occupational hazard for people who sorted wool. Today, this form of infection is extremely rare in advanced nations, as almost no infected animals remain.

Mode of infection

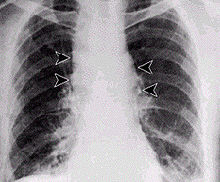

Inhalational anthrax, mediastinal widening

Anthrax can enter the human body through the intestines (ingestion),

lungs (inhalation), or skin (cutaneous) and causes distinct clinical

symptoms based on its site of entry. In general, an infected human is

quarantined. However, anthrax does not usually spread from an infected

human to an uninfected human.

If the disease is fatal to the person's body, though, its mass of

anthrax bacilli becomes a potential source of infection to others and

special precautions should be used to prevent further contamination.

Inhalational anthrax, if left untreated until obvious symptoms occur, is

usually fatal.

Anthrax can be contracted in laboratory accidents or by handling infected animals, their wool, or their hides. It has also been used in biological warfare agents and by terrorists to intentionally infect as exemplified by the 2001 anthrax attacks.

Mechanism

The lethality of the anthrax disease is due to the bacterium's two principal virulence factors: the poly-D-glutamic acid capsule, which protects the bacterium from phagocytosis by host neutrophils, and the tripartite protein toxin, called anthrax toxin. Anthrax toxin is a mixture of three protein components: protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF), and lethal factor (LF). PA plus LF produces lethal toxin, and PA plus EF produces edema toxin. These toxins cause death and tissue swelling (edema), respectively.

To enter the cells, the edema and lethal factors use another protein produced by B. anthracis called protective antigen, which binds to two surface receptors on the host cell. A cell protease then cleaves PA into two fragments: PA20 and PA63. PA20 dissociates into the extracellular medium, playing no further role in the toxic cycle. PA63 then oligomerizes with six other PA63

fragments forming a heptameric ring-shaped structure named a prepore.

Once in this shape, the complex can competitively bind up to three EFs

or LFs, forming a resistant complex.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis occurs next, providing the newly formed

toxic complex access to the interior of the host cell. The acidified

environment within the endosome triggers the heptamer to release the LF

and/or EF into the cytosol. It is unknown how exactly the complex results in the death of the cell.

Edema factor is a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase. Adenylate cyclase catalyzes the conversion of ATP into cyclic AMP (cAMP) and pyrophosphate. The complexation of adenylate cyclase with calmodulin removes calmodulin from stimulating calcium-triggered signaling, thus inhibiting the immune response. To be specific, LF inactivates neutrophils

(a type of phagocytic cell) by the process just described so they

cannot phagocytose bacteria. Throughout history, lethal factor was

presumed to cause macrophages to make TNF-alpha and interleukin 1, beta (IL1B). TNF-alpha is a cytokine whose primary role is to regulate immune cells, as well as to induce inflammation and apoptosis

or programmed cell death. Interleukin 1, beta is another cytokine that

also regulates inflammation and apoptosis. The overproduction of

TNF-alpha and IL1B ultimately leads to septic shock and death. However, recent evidence indicates anthrax also targets endothelial cells that line serous cavities such as the pericardial cavity, pleural cavity, and peritoneal cavity, lymph vessels, and blood vessels, causing vascular leakage of fluid and cells, and ultimately hypovolemic shock and septic shock.

Diagnosis

Various techniques may be used for the direct identification of B. anthracis in clinical material. Firstly, specimens may be Gram stained. Bacillus

spp. are quite large in size (3 to 4 μm long), they may grow in long

chains, and they stain Gram-positive. To confirm the organism is B. anthracis, rapid diagnostic techniques such as polymerase chain reaction-based assays and immunofluorescence microscopy may be used.

All Bacillus species grow well on 5% sheep blood agar and

other routine culture media. Polymyxin-lysozyme-EDTA-thallous acetate

can be used to isolate B. anthracis from contaminated specimens, and bicarbonate agar is used as an identification method to induce capsule formation. Bacillus spp. usually grow within 24 hours of incubation at 35 °C, in ambient air (room temperature) or in 5% CO2. If bicarbonate agar is used for identification, then the medium must be incubated in 5% CO2. B. anthracis colonies are medium-large, gray, flat, and irregular with swirling projections, often referred to as having a "medusa head"

appearance, and are not hemolytic on 5% sheep blood agar. The bacteria

are not motile, susceptible to penicillin, and produce a wide zone of

lecithinase on egg yolk agar. Confirmatory testing to identify B. anthracis includes gamma bacteriophage testing, indirect hemagglutination, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect antibodies. The best confirmatory precipitation test for anthrax is the Ascoli test.

Prevention

If a person is suspected as having died from anthrax, precautions

should be taken to avoid skin contact with the potentially contaminated

body and fluids exuded through natural body openings. The body should be

put in strict quarantine. A blood sample should then be collected and

sealed in a container and analyzed in an approved laboratory to

ascertain if anthrax is the cause of death. Then, the body should be

incinerated. Microscopic visualization of the encapsulated bacilli,

usually in very large numbers, in a blood smear stained with polychrome

methylene blue (McFadyean stain) is fully diagnostic, though culture of

the organism is still the gold standard for diagnosis. Full isolation of

the body is important to prevent possible contamination of others.

Protective, impermeable clothing and equipment such as rubber gloves,

rubber apron, and rubber boots with no perforations should be used when

handling the body. No skin, especially if it has any wounds or

scratches, should be exposed. Disposable personal protective equipment

is preferable, but if not available, decontamination can be achieved by

autoclaving. Disposable personal protective equipment and filters should

be autoclaved, and/or burned and buried. Anyone working with anthrax

in a suspected or confirmed person should wear respiratory equipment

capable of filtering particles of their size or smaller. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – and Mine Safety and Health Administration-approved

high-efficiency respirator, such as a half-face disposable respirator

with a high-efficiency particulate air filter, is recommended.

All possibly contaminated bedding or clothing should be isolated in

double plastic bags and treated as possible biohazard waste. The body of

an infected person should be sealed in an airtight body bag. Dead

people who are opened and not burned provide an ideal source of anthrax

spores. Cremating people is the preferred way of handling body disposal.

No embalming or autopsy should be attempted without a fully equipped

biohazard laboratory and trained, knowledgeable personnel.

Vaccines

Vaccines against anthrax for use in livestock and humans have had a

prominent place in the history of medicine. The French scientist Louis Pasteur developed the first effective vaccine in 1881. Human anthrax vaccines were developed by the Soviet Union in the late 1930s and in the US and UK in the 1950s. The current FDA-approved US vaccine was formulated in the 1960s.

Currently administered human anthrax vaccines include acellular (United States) and live vaccine (Russia) varieties. All currently used anthrax vaccines show considerable local and general reactogenicity (erythema, induration, soreness, fever) and serious adverse reactions occur in about 1% of recipients.

The American product, BioThrax, is licensed by the FDA and was formerly

administered in a six-dose primary series at 0, 2, 4 weeks and 6, 12,

18 months, with annual boosters to maintain immunity. In 2008, the FDA

approved omitting the week-2 dose, resulting in the currently

recommended five-dose series. New second-generation vaccines currently being researched include recombinant live vaccines and recombinant subunit vaccines. In the 20th century the use of a modern product (BioThrax) to protect American troops against the use of anthrax in biological warfare was controversial.

Antibiotics

Preventive antibiotics are recommended in those who have been exposed.

Early detection of sources of anthrax infection can allow preventive

measures to be taken. In response to the anthrax attacks of October

2001, the United States Postal Service

(USPS) installed biodetection systems (BDSs) in their large-scale mail

processing facilities. BDS response plans were formulated by the USPS in

conjunction with local responders including fire, police, hospitals,

and public health. Employees of these facilities have been educated

about anthrax, response actions, and prophylactic

medication. Because of the time delay inherent in getting final

verification that anthrax has been used, prophylactic antibiotic

treatment of possibly exposed personnel must be started as soon as

possible.

Treatment

Anthrax cannot be spread directly from person to person, but a

person's clothing and body may be contaminated with anthrax spores.

Effective decontamination of people can be accomplished by a thorough

wash-down with antimicrobial soap and water. Waste water should be treated with bleach or another antimicrobial agent.

Effective decontamination of articles can be accomplished by boiling

them in water for 30 minutes or longer. Chlorine bleach is ineffective

in destroying spores and vegetative cells on surfaces, though formaldehyde

is effective. Burning clothing is very effective in destroying spores.

After decontamination, there is no need to immunize, treat, or isolate

contacts of persons ill with anthrax unless they were also exposed to

the same source of infection.

Antibiotics

Early antibiotic treatment of anthrax is essential; delay significantly lessens chances for survival.

Treatment for anthrax infection and other bacterial infections

includes large doses of intravenous and oral antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), doxycycline, erythromycin, vancomycin, or penicillin. FDA-approved agents include ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and penicillin.

In possible cases of pulmonary anthrax, early antibiotic prophylaxis treatment is crucial to prevent possible death.

In recent years, many attempts have been made to develop new

drugs against anthrax, but existing drugs are effective if treatment is

started soon enough.

Monoclonal antibodies

In May 2009, Human Genome Sciences submitted a biologic license application (BLA, permission to market) for its new drug, raxibacumab (brand name ABthrax) intended for emergency treatment of inhaled anthrax.

On 14 December 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved

raxibacumab injection to treat inhalational anthrax. Raxibacumab is a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes toxins produced by B. anthracis. On March, 2016, FDA approved a second anthrax treatment using a monoclonal antibody which neutralizes the toxins produced by B. anthracis. Obiltoxaximab is approved to treat inhalational anthrax in conjunction with appropriate antibacterial drugs, and for prevention when alternative therapies are not available or appropriate.

Epidemiology

Globally, at least 2,000 cases occur a year.

United States

The

last fatal case of natural inhalational anthrax in the United States

occurred in California in 1976, when a home weaver died after working

with infected wool imported from Pakistan. To minimize the chance of

spreading the disease, the deceased was transported to UCLA in a sealed plastic body bag within a sealed metal container for autopsy.

Gastrointestinal anthrax is exceedingly rare in the United

States, with only two cases on record. The first case was reported in

1942, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During December 2009, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human

Services confirmed a case of gastrointestinal anthrax in an adult

female.

The CDC

investigated the source of the December 2009 infection and the

possibility that it was contracted from an African drum recently used by

the woman taking part in a drum circle.

The woman apparently inhaled anthrax, in spore form, from the hide of

the drum. She became critically ill, but with gastrointestinal anthrax

rather than inhaled anthrax, which made her unique in American medical

history. The building where the infection took place was cleaned and

reopened to the public and the woman recovered. The New Hampshire state

epidemiologist, Jodie Dionne-Odom, stated "It is a mystery. We really

don't know why it happened."

United Kingdom

In November 2008, a drum maker in the United Kingdom who worked with untreated animal skins died from anthrax. In December 2009, an outbreak of anthrax occurred amongst heroin addicts in the Glasgow and Stirling areas of Scotland, resulting in 14 deaths. The source of the anthrax is believed to be dilution of the heroin with bone meal in Afghanistan.

Etymology

The English name comes from anthrax (ἄνθραξ), the Greek word for coal, possibly having Egyptian etymology, because of the characteristic black skin lesions developed by victims with a cutaneous anthrax infection. The central, black eschar,

surrounded by vivid red skin has long been recognised as typical of the

disease. The first recorded use of the word "anthrax" in English is in a

1398 translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus' work De proprietatibus rerum (On the Properties of Things, 1240).

Anthrax has been known by a wide variety of names, indicating its

symptoms, location and groups considered most vulnerable to infection.

These include Siberian plague, Cumberland disease, charbon, splenic fever, malignant edema, woolsorter's disease, and even la maladie de Bradford.

Discovery

Robert Koch, a German physician and scientist, first identified the bacterium that caused the anthrax disease in 1875 in Wolsztyn (now part of Poland).

His pioneering work in the late 19th century was one of the first

demonstrations that diseases could be caused by microbes. In a

groundbreaking series of experiments, he uncovered the lifecycle and

means of transmission of anthrax. His experiments not only helped create

an understanding of anthrax, but also helped elucidate the role of

microbes in causing illness at a time when debates still took place over

spontaneous generation versus cell theory. Koch went on to study the mechanisms of other diseases and won the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the bacterium causing tuberculosis.

Although Koch arguably made the greatest theoretical contribution

to understanding anthrax, other researchers were more concerned with

the practical questions of how to prevent the disease. In Britain, where

anthrax affected workers in the wool, worsted, hides, and tanning industries, it was viewed with fear. John Henry Bell, a doctor based in Bradford,

first made the link between the mysterious and deadly "woolsorter's

disease" and anthrax, showing in 1878 that they were one and the same. In the early 20th century, Friederich Wilhelm Eurich, the German bacteriologist

who settled in Bradford with his family as a child, carried out

important research for the local Anthrax Investigation Board. Eurich

also made valuable contributions to a Home Office Departmental Committee of Inquiry, established in 1913 to address the continuing problem of industrial anthrax. His work in this capacity, much of it collaboration with the factory inspector G. Elmhirst Duckering, led directly to the Anthrax Prevention Act (1919).

First vaccination

Louis Pasteur inoculating sheep against anthrax

Anthrax posed a major economic challenge in France

and elsewhere during the 19th century. Horses, cattle, and sheep were

particularly vulnerable, and national funds were set aside to

investigate the production of a vaccine. Noted French scientist Louis Pasteur

was charged with the production of a vaccine, following his successful

work in developing methods which helped to protect the important wine

and silk industries.

In May 1881, Pasteur – in collaboration with his assistants Jean-Joseph Henri Toussaint, Émile Roux and others – performed a public experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort to demonstrate his concept of vaccination. He prepared two groups of 25 sheep, one goat, and several cattle.

The animals of one group were injected with an anthrax vaccine prepared

by Pasteur twice, at an interval of 15 days; the control group was left

unvaccinated. Thirty days after the first injection, both groups were

injected with a culture of live anthrax bacteria. All the animals in the

unvaccinated group died, while all of the animals in the vaccinated

group survived.

After this apparent triumph, which was widely reported in the

local, national, and international press, Pasteur made strenuous efforts

to export the vaccine beyond France. He used his celebrity status to

establish Pasteur Institutes across Europe and Asia, and his nephew, Adrien Loir, travelled to Australia in 1888 to try to introduce the vaccine to combat anthrax in New South Wales.

Ultimately, the vaccine was unsuccessful in the challenging climate of

rural Australia, and it was soon superseded by a more robust version

developed by local researchers John Gunn and John McGarvie Smith.

The human vaccine for anthrax

became available in 1954. This was a cell-free vaccine instead of the

live-cell Pasteur-style vaccine used for veterinary purposes. An

improved cell-free vaccine became available in 1970.

Engineered strains

- The Sterne strain of anthrax, named after the Trieste-born immunologist Max Sterne, is an attenuated strain used as a vaccine, which contains only the anthrax toxin virulence plasmid and not the polyglutamic acid capsule expressing plasmid.

- Strain 836, created by the Soviet bio-weapons program in the 1980s, was later called by the Los Angeles Times as "the most virulent and vicious strain of anthrax known to man".

- The virulent Ames strain, which was used in the 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States, has received the most news coverage of any anthrax outbreak. The Ames strain contains two virulence plasmids, which separately encode for a three-protein toxin, called anthrax toxin, and a polyglutamic acid capsule.

- Nonetheless, the Vollum strain, developed but never used as a biological weapon during the Second World War, is much more dangerous. The Vollum (also incorrectly referred to as Vellum) strain was isolated in 1935 from a cow in Oxfordshire. This same strain was used during the Gruinard bioweapons trials. A variation of Vollum, known as "Vollum 1B", was used during the 1960s in the US and UK bioweapon programs. Vollum 1B is widely believed to have been isolated from William A. Boyles, a 46-year-old scientist at the US Army Biological Warfare Laboratories at Camp (later Fort) Detrick, Maryland, who died in 1951 after being accidentally infected with the Vollum strain.

Society and culture

Site cleanup

Anthrax

spores can survive for very long periods of time in the environment

after release. Chemical methods for cleaning anthrax-contaminated sites

or materials may use oxidizing agents such as peroxides, ethylene oxide, Sandia Foam, chlorine dioxide (used in the Hart Senate Office Building),

peracetic acid, ozone gas, hypochlorous acid, sodium persulfate, and

liquid bleach products containing sodium hypochlorite. Nonoxidizing

agents shown to be effective for anthrax decontamination include methyl

bromide, formaldehyde, and metam sodium. These agents destroy bacterial

spores. All of the aforementioned anthrax decontamination technologies

have been demonstrated to be effective in laboratory tests conducted by

the US EPA or others.

Decontamination techniques for Bacillus anthracis spores

are affected by the material with which the spores are associated,

environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, and

microbiological factors such as the spore species, anthracis strain, and

test methods used.

A bleach solution for treating hard surfaces has been approved by the EPA. Chlorine dioxide

has emerged as the preferred biocide against anthrax-contaminated

sites, having been employed in the treatment of numerous government

buildings over the past decade. Its chief drawback is the need for in situ processes to have the reactant on demand.

To speed the process, trace amounts of a nontoxic catalyst composed of iron and tetroamido macrocyclic ligands are combined with sodium carbonate and bicarbonate and converted into a spray. The spray formula is applied to an infested area and is followed by another spray containing tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

Using the catalyst method, a complete destruction of all anthrax spores can be achieved in under 30 minutes. A standard catalyst-free spray destroys fewer than half the spores in the same amount of time.

Cleanups at a Senate Office Building, several contaminated postal

facilities, and other US government and private office buildings, a

collaborative effort headed by the Environmental Protection Agency

showed decontamination to be possible, but time-consuming and costly.

Clearing the Senate Office Building of anthrax spores cost $27 million,

according to the Government Accountability Office. Cleaning the

Brentwood postal facility in Washington cost $130 million and took 26

months. Since then, newer and less costly methods have been developed.

Cleanup of anthrax-contaminated areas on ranches and in the wild is much more problematic. Carcasses may be burned,

though often 3 days are needed to burn a large carcass and this is not

feasible in areas with little wood. Carcasses may also be buried, though

the burying of large animals deeply enough to prevent resurfacing of

spores requires much manpower and expensive tools. Carcasses have been

soaked in formaldehyde to kill spores, though this has environmental

contamination issues. Block burning of vegetation in large areas

enclosing an anthrax outbreak has been tried; this, while

environmentally destructive, causes healthy animals to move away from an

area with carcasses in search of fresh grass. Some wildlife workers

have experimented with covering fresh anthrax carcasses with shadecloth

and heavy objects. This prevents some scavengers from opening the

carcasses, thus allowing the putrefactive bacteria within the carcass to

kill the vegetative B. anthracis cells and preventing

sporulation. This method also has drawbacks, as scavengers such as

hyenas are capable of infiltrating almost any exclosure.

The experimental site at Gruinard Island is said to have been decontaminated with a mixture of formaldehyde and seawater by the Ministry of Defence. It is not clear whether similar treatments had been applied to US test sites.

Biological warfare

Colin Powell giving a presentation to the United Nations Security Council, holding a model vial of anthrax

Anthrax spores have been used as a biological warfare

weapon. Its first modern incidence occurred when Nordic rebels,

supplied by the German General Staff, used anthrax with unknown results

against the Imperial Russian Army in Finland in 1916. Anthrax was first tested as a biological warfare agent by Unit 731 of the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria

during the 1930s; some of this testing involved intentional infection

of prisoners of war, thousands of whom died. Anthrax, designated at the

time as Agent N, was also investigated by the Allies in the 1940s.

A long history of practical bioweapons research exists in this area. For example, in 1942, British bioweapons trials severely contaminated Gruinard Island in Scotland with anthrax spores of the Vollum-14578 strain, making it a no-go area until it was decontaminated in 1990. The Gruinard trials involved testing the effectiveness of a submunition

of an "N-bomb" – a biological weapon containing dried anthrax spores.

Additionally, five million "cattle cakes" (animal feed pellets

impregnated with anthrax spores) were prepared and stored at Porton Down for "Operation Vegetarian" – antilivestock attacks against Germany to be made by the Royal Air Force.

The plan was for anthrax-based biological weapons to be dropped on

Germany in 1944. However, the edible cattle cakes and the bomb were not

used; the cattle cakes were incinerated in late 1945.

Weaponized anthrax was part of the US stockpile prior to 1972, when the United States signed the Biological Weapons Convention. President Nixon

ordered the dismantling of US biowarfare programs in 1969 and the

destruction of all existing stockpiles of bioweapons. In 1978–79, the Rhodesian government used anthrax against cattle and humans during its campaign against rebels. The Soviet Union created and stored 100 to 200 tons of anthrax spores at Kantubek on Vozrozhdeniya Island. They were abandoned in 1992 and destroyed in 2002.

American military and British Army

personnel are routinely vaccinated against anthrax prior to active

service in places where biological attacks are considered a threat.

Sverdlovsk incident (2 April 1979)

Despite signing the 1972 agreement to end bioweapon production, the

government of the Soviet Union had an active bioweapons program that

included the production of hundreds of tons of anthrax after this

period. On 2 April 1979, some of the over one million people living in

Sverdlovsk (now called Ekaterinburg, Russia), about 850 miles (1,370 km) east of Moscow, were exposed to an accidental release of anthrax

from a biological weapons complex located near there. At least 94

people were infected, of whom at least 68 died. One victim died four

days after the release, 10 over an eight-day period at the peak of the

deaths, and the last six weeks later. Extensive cleanup, vaccinations,

and medical interventions managed to save about 30 of the victims. Extensive cover-ups and destruction of records by the KGB continued from 1979 until Russian President Boris Yeltsin

admitted this anthrax accident in 1992. Jeanne Guillemin reported in

1999 that a combined Russian and United States team investigated the

accident in 1992.

Nearly all of the night-shift workers of a ceramics plant

directly across the street from the biological facility (compound 19)

became infected, and most died. Since most were men, some NATO governments suspected the Soviet Union had developed a sex-specific weapon.

The government blamed the outbreak on the consumption of

anthrax-tainted meat, and ordered the confiscation of all uninspected

meat that entered the city. They also ordered all stray dogs

to be shot and people not have contact with sick animals. Also, a

voluntary evacuation and anthrax vaccination program was established for

people from 18–55.

To support the cover-up

story, Soviet medical and legal journals published articles about an

outbreak in livestock that caused GI anthrax in people having consumed

infected meat, and cutaneous anthrax in people having come into contact

with the animals. All medical and public health records were confiscated

by the KGB.

In addition to the medical problems the outbreak caused, it also

prompted Western countries to be more suspicious of a covert Soviet

bioweapons program and to increase their surveillance of suspected

sites. In 1986, the US government was allowed to investigate the

incident, and concluded the exposure was from aerosol anthrax from a

military weapons facility.

In 1992, President Yeltsin admitted he was "absolutely certain" that

"rumors" about the Soviet Union violating the 1972 Bioweapons Treaty

were true. The Soviet Union, like the US and UK, had agreed to submit

information to the UN about their bioweapons programs, but omitted known

facilities and never acknowledged their weapons program.

Anthrax bioterrorism

In theory, anthrax spores can be cultivated with minimal special equipment and a first-year collegiate microbiological education.

To make large amounts of an aerosol

form of anthrax suitable for biological warfare requires extensive

practical knowledge, training, and highly advanced equipment.

Concentrated anthrax spores were used for bioterrorism in the 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States, delivered by mailing postal letters containing the spores. The letters were sent to several news media offices and two Democratic senators: Tom Daschle of South Dakota and Patrick Leahy of Vermont. As a result, 22 were infected and five died.

Only a few grams of material were used in these attacks and in August

2008, the US Department of Justice announced they believed that Bruce Ivins, a senior biodefense researcher employed by the United States government, was responsible. These events also spawned many anthrax hoaxes.

Due to these events, the US Postal Service installed biohazard detection systems at its major distribution centers to actively scan for anthrax being transported through the mail. As of 2013, positive alerts by these systems have occurred.

Decontaminating mail

In response to the postal anthrax attacks and hoaxes, the United States Postal Service sterilized some mail using gamma irradiation and treatment with a proprietary enzyme formula supplied by Sipco Industries.

A scientific experiment performed by a high school student, later published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology, suggested a domestic electric iron

at its hottest setting (at least 400 °F (204 °C)) used for at least 5

minutes should destroy all anthrax spores in a common postal envelope.

Popular culture

In Aldous Huxley's 1932 dystopian novel Brave New World,

anthrax bombs are mentioned as the primary weapon by means of which

original modern society is terrorised and in big part eradicated, to be

replaced by a dystopian society.

Anthrax attacks have featured in the storylines of various television episodes and films. A Criminal Minds episode follows the attempt to identify an attacker who released anthrax spores in a public park.

Other animals

Anthrax is especially rare in dogs and cats, as is evidenced by a single reported case in the United States in 2001. Anthrax outbreaks occur in some wild animal populations with some regularity.

Russian researchers estimate arctic permafrost contains around 1.5 million anthrax-infected reindeer carcasses, and the spores may survive in the permafrost for 105 years. A risk exists that global warming in the Arctic

can thaw the permafrost, releasing anthrax spores in the carcasses. In

2016, an anthrax outbreak in reindeer was linked to a 75-year-old

carcass that defrosted during a heat wave.