Genetic linkage is the tendency of DNA sequences that are close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during the meiosis phase of sexual reproduction. Two genetic markers that are physically near to each other are unlikely to be separated onto different chromatids during chromosomal crossover, and are therefore said to be more linked than markers that are far apart. In other words, the nearer two genes are on a chromosome, the lower the chance of recombination between them, and the more likely they are to be inherited together. Markers on different chromosomes are perfectly unlinked.

Genetic linkage is the most prominent exception to Gregor Mendel's Law of Independent Assortment. The first experiment to demonstrate linkage was carried out in 1905. At the time, the reason why certain traits tend to be inherited together was unknown. Later work revealed that genes are physical structures related by physical distance.

The typical unit of genetic linkage is the centimorgan (cM). A distance of 1 cM between two markers means that the markers are separated to different chromosomes on average once per 100 meiotic product, thus once per 50 meioses...

Genetic linkage is the most prominent exception to Gregor Mendel's Law of Independent Assortment. The first experiment to demonstrate linkage was carried out in 1905. At the time, the reason why certain traits tend to be inherited together was unknown. Later work revealed that genes are physical structures related by physical distance.

The typical unit of genetic linkage is the centimorgan (cM). A distance of 1 cM between two markers means that the markers are separated to different chromosomes on average once per 100 meiotic product, thus once per 50 meioses...

Discovery

Gregor Mendel's Law of Independent Assortment states that every trait is inherited independently of every other trait. But shortly after Mendel's work was rediscovered, exceptions to this rule were found. In 1905, the British geneticists William Bateson, Edith Rebecca Saunders and Reginald Punnett cross-bred pea plants in experiments similar to Mendel's. They were interested in trait inheritance in the sweet pea and were studying two genes—the gene for flower colour (P, purple, and p, red) and the gene affecting the shape of pollen grains (L, long, and l, round). They crossed the pure lines PPLL and ppll and then self-crossed the resulting PpLl lines.

According to Mendelian genetics, the expected phenotypes

would occur in a 9:3:3:1 ratio of PL:Pl:pL:pl. To their surprise, they

observed an increased frequency of PL and pl and a decreased frequency

of Pl and pL:

| Phenotype and genotype | Observed | Expected from 9:3:3:1 ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Purple, long (P_L_) | 284 | 216 |

| Purple, round (P_ll) | 21 | 72 |

| Red, long (ppL_) | 21 | 72 |

| Red, round (ppll) | 55 | 24 |

Their experiment revealed linkage between the P and L alleles and the p and l alleles. The frequency of P occurring together with L and p occurring together with l is greater than that of the recombinant Pl and pL. The recombination frequency is more difficult to compute in an F2 cross than a backcross,

but the lack of fit between observed and expected numbers of progeny in

the above table indicate it is less than 50%. This indicated that two

factors interacted in some way to create this difference by masking the

appearance of the other two phenotypes. This led to the conclusion that

some traits are related to each other because of their near proximity to

each other on a chromosome. This provided the grounds to determine the

difference between independent and codependent alleles.

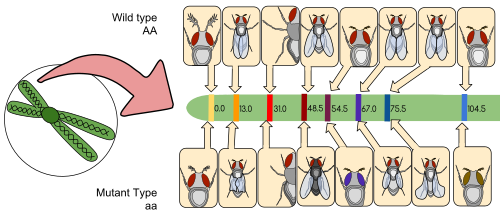

The understanding of linkage was expanded by the work of Thomas Hunt Morgan. Morgan's observation that the amount of crossing over between linked genes differs led to the idea that crossover frequency might indicate the distance separating genes on the chromosome. The centimorgan, which expresses the frequency of crossing over, is named in his honour.

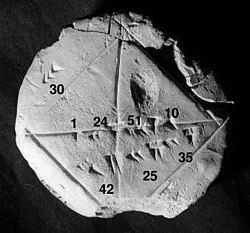

Linkage map

Thomas Hunt Morgan's Drosophila melanogaster genetic linkage map. This was the first successful gene mapping work and provides important evidence for the chromosome theory of inheritance. The map shows the relative positions of alleles on the second Drosophila chromosome. The distances between the genes (centimorgans) are equal to the percentages of chromosomal crossover events that occur between different alleles.

A linkage map (also known as a genetic map) is a table for a species or experimental population that shows the position of its known genes or genetic markers

relative to each other in terms of recombination frequency, rather than

a specific physical distance along each chromosome. Linkage maps were

first developed by Alfred Sturtevant, a student of Thomas Hunt Morgan.

A linkage map is a map based on the frequencies of recombination between markers during crossover of homologous chromosomes.

The greater the frequency of recombination (segregation) between two

genetic markers, the further apart they are assumed to be. Conversely,

the lower the frequency of recombination between the markers, the

smaller the physical distance between them. Historically, the markers

originally used were detectable phenotypes (enzyme production, eye colour) derived from coding DNA sequences; eventually, confirmed or assumed noncoding DNA sequences such as microsatellites or those generating restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) have been used.

Linkage maps help researchers to

locate other markers, such as other genes by testing for genetic linkage

of the already known markers. In the early stages of developing a

linkage map, the data are used to assemble linkage groups, a set

of genes which are known to be linked. As knowledge advances, more

markers can be added to a group, until the group covers an entire

chromosome. For well-studied organisms the linkage groups correspond one-to-one with the chromosomes.

A linkage map is not a physical map (such as a radiation reduced hybrid map) or gene map.

Linkage analysis

Linkage analysis is a genetic method that searches for chromosomal segments that cosegregate with the ailment phenotype through families and is the analysis technique that has been used to determine the bulk of lipodystrophy genes. It can be used to map genes for both binary and quantitative traits.

Linkage analysis may be either parametric (if we know the relationship

between phenotypic and genetic similarity) or non-parametric. Parametric

linkage analysis is the traditional approach, whereby the probability

that a gene important for a disease is linked to a genetic marker is

studied through the LOD score, which assesses the probability that a

given pedigree, where the disease and the marker are cosegregating, is

due to the existence of linkage (with a given linkage value) or to

chance. Non-parametric linkage analysis, in turn, studies the

probability of an allele being identical by descent with itself.

Parametric linkage analysis

The LOD score (logarithm (base 10) of odds), developed by Newton Morton,

is a statistical test often used for linkage analysis in human, animal,

and plant populations. The LOD score compares the likelihood of

obtaining the test data if the two loci are indeed linked, to the

likelihood of observing the same data purely by chance. Positive LOD

scores favour the presence of linkage, whereas negative LOD scores

indicate that linkage is less likely. Computerised LOD score analysis is

a simple way to analyse complex family pedigrees in order to determine

the linkage between Mendelian traits (or between a trait and a marker, or two markers).

The method is described in greater detail by Strachan and Read. Briefly, it works as follows:

- Establish a pedigree

- Make a number of estimates of recombination frequency

- Calculate a LOD score for each estimate

- The estimate with the highest LOD score will be considered the best estimate

The LOD score is calculated as follows:

NR denotes the number of non-recombinant offspring, and R denotes the

number of recombinant offspring. The reason 0.5 is used in the

denominator is that any alleles that are completely unlinked (e.g.

alleles on separate chromosomes) have a 50% chance of recombination, due

to independent assortment. θ is the recombinant fraction, i.e.

the fraction of births in which recombination has happened between the

studied genetic marker and the putative gene associated with the

disease. Thus, it is equal to R / (NR + R).

By convention, a LOD score greater than 3.0 is considered

evidence for linkage, as it indicates 1000 to 1 odds that the linkage

being observed did not occur by chance. On the other hand, a LOD score

less than −2.0 is considered evidence to exclude linkage. Although it is

very unlikely that a LOD score of 3 would be obtained from a single

pedigree, the mathematical properties of the test allow data from a

number of pedigrees to be combined by summing their LOD scores. A LOD

score of 3 translates to a p-value of approximately 0.05, and no multiple testing correction (e.g. Bonferroni correction) is required.

Limitations

Linkage analysis has a number of methodological and theoretical limitations that can significantly increase the type-1 error rate and reduce the power to map human quantitative trait loci (QTL). While linkage analysis was successfully used to identify genetic variants that contribute to rare disorders such as Huntington disease, it did not perform that well when applied to more common disorders such as heart disease or different forms of cancer.

An explanation for this is that the genetic mechanisms affecting common

disorders are different from those causing rare disorders.

Recombination frequency

Recombination

frequency is a measure of genetic linkage and is used in the creation

of a genetic linkage map. Recombination frequency (θ) is the frequency with which a single chromosomal crossover will take place between two genes during meiosis. A centimorgan

(cM) is a unit that describes a recombination frequency of 1%. In this

way we can measure the genetic distance between two loci, based upon

their recombination frequency. This is a good estimate of the real

distance. Double crossovers would turn into no recombination. In this

case we cannot tell if crossovers took place. If the loci we're

analysing are very close (less than 7 cM) a double crossover is very

unlikely. When distances become higher, the likelihood of a double

crossover increases. As the likelihood of a double crossover increases

we systematically underestimate the genetic distance between two loci.

During meiosis, chromosomes assort randomly into gametes, such that the segregation of alleles of one gene is independent of alleles of another gene. This is stated in Mendel's Second Law and is known as the law of independent assortment.

The law of independent assortment always holds true for genes that are

located on different chromosomes, but for genes that are on the same

chromosome, it does not always hold true.

As an example of independent assortment, consider the crossing of the pure-bred homozygote parental strain with genotype AABB with a different pure-bred strain with genotype aabb.

A and a and B and b represent the alleles of genes A and B. Crossing

these homozygous parental strains will result in F1 generation offspring

that are double heterozygotes with genotype AaBb. The F1 offspring AaBb produces gametes that are AB, Ab, aB, and ab

with equal frequencies (25%) because the alleles of gene A assort

independently of the alleles for gene B during meiosis. Note that 2 of

the 4 gametes (50%)—Ab and aB—were not present in the parental generation. These gametes represent recombinant gametes. Recombinant gametes are those gametes that differ from both of the haploid gametes that made up the original diploid cell. In this example, the recombination frequency is 50% since 2 of the 4 gametes were recombinant gametes.

The recombination frequency will be 50% when two genes are located on different chromosomes or when they are widely separated on the same chromosome. This is a consequence of independent assortment.

When two genes are close together on the same chromosome, they do

not assort independently and are said to be linked. Whereas genes

located on different chromosomes assort independently and have a

recombination frequency of 50%, linked genes have a recombination

frequency that is less than 50%.

As an example of linkage, consider the classic experiment by William Bateson and Reginald Punnett. They were interested in trait inheritance in the sweet pea and were studying two genes—the gene for flower colour (P, purple, and p, red) and the gene affecting the shape of pollen grains (L, long, and l, round). They crossed the pure lines PPLL and ppll and then self-crossed the resulting PpLl lines. According to Mendelian genetics, the expected phenotypes

would occur in a 9:3:3:1 ratio of PL:Pl:pL:pl. To their surprise, they

observed an increased frequency of PL and pl and a decreased frequency

of Pl and pL (see table below).

| Phenotype and genotype | Observed | Expected from 9:3:3:1 ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Purple, long (P_L_) | 284 | 216 |

| Purple, round (P_ll) | 21 | 72 |

| Red, long (ppL_) | 21 | 72 |

| Red, round (ppll) | 55 | 24 |

Their experiment revealed linkage between the P and L alleles and the p and l alleles. The frequency of P occurring together with L and with p occurring together with l is greater than that of the recombinant Pl and pL. The recombination frequency is more difficult to compute in an F2 cross than a backcross, but the lack of fit between observed and expected numbers of progeny in the above table indicate it is less than 50%.

The progeny in this case received two dominant alleles linked on one chromosome (referred to as coupling or cis arrangement).

However, after crossover, some progeny could have received one parental

chromosome with a dominant allele for one trait (e.g. Purple) linked to

a recessive allele for a second trait (e.g. round) with the opposite

being true for the other parental chromosome (e.g. red and Long). This

is referred to as repulsion or a trans arrangement. The phenotype

here would still be purple and long but a test cross of this individual

with the recessive parent would produce progeny with much greater

proportion of the two crossover phenotypes. While such a problem may not

seem likely from this example, unfavourable repulsion linkages do

appear when breeding for disease resistance in some crops.

The two possible arrangements, cis and trans, of alleles in a double heterozygote are referred to as gametic phases, and phasing is the process of determining which of the two is present in a given individual.

When two genes are located on the same chromosome, the chance of a crossover

producing recombination between the genes is related to the distance

between the two genes. Thus, the use of recombination frequencies has

been used to develop linkage maps or genetic maps.

However, it is important to note that recombination frequency

tends to underestimate the distance between two linked genes. This is

because as the two genes are located farther apart, the chance of double

or even number of crossovers between them also increases. Double or

even number of crossovers between the two genes results in them being

cosegregated to the same gamete, yielding a parental progeny instead of

the expected recombinant progeny. As mentioned above, the Kosambi and

Haldane transformations attempt to correct for multiple crossovers.

Variation of recombination frequency

While

recombination of chromosomes is an essential process during meiosis,

there is a large range of frequency of cross overs across organisms and

within species. Sexually dimorphic rates of recombination are termed

heterochiasmy, and are observed more often than a common rate between

male and females. In mammals, females often have a higher rate of

recombination compared to males. It is theorised that there are unique

selections acting or meiotic drivers which influence the difference in

rates. The difference in rates may also reflect the vastly different

environments and conditions of meiosis in oogenesis and spermatogenesis.

Meiosis indicators

With

very large pedigrees or with very dense genetic marker data, such as

from whole-genome sequencing, it is possible to precisely locate

recombinations. With this type of genetic analysis, a meiosis indicator

is assigned to each position of the genome for each meiosis

in a pedigree. The indicator indicates which copy of the parental

chromosome contributes to the transmitted gamete at that position. For

example, if the allele from the 'first' copy of the parental chromosome

is transmitted, a '0' might be assigned to that meiosis. If the allele

from the 'second' copy of the parental chromosome is transmitted, a '1'

would be assigned to that meiosis. The two alleles in the parent came,

one each, from two grandparents. These indicators are then used to

determine identical-by-descent (IBD) states or inheritance states, which

are in turn used to identify genes responsible for diseases.