The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia [diˈviːna komˈmɛːdja]) is a long Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed in 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is widely considered to be the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of the greatest works of world literature. The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written (also in most present-day Italian-market editions), as the standardized Italian language. It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

The narrative describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise or Heaven, while allegorically the poem represents the soul's journey towards God. Dante draws on medieval Christian theology and philosophy, especially Thomistic philosophy derived from the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas. Consequently, the Divine Comedy has been called "the Summa in verse". In Dante's work, Virgil is presented as human reason and Beatrice is presented as divine knowledge.

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa (pronounced [komeˈdiːa]; so also in the first printed edition, published in 1472), Tuscan for "Comedy", later adjusted to the modern Italian Commedia. The adjective Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio, and the first edition to name the poem Divina Comedia in the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce, published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

Structure and story

The Divine Comedy is composed of 14,233 lines that are divided into three cantiche (singular cantica) – Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) – each consisting of 33 cantos (Italian plural canti). An initial canto, serving as an introduction to the poem and generally considered to be part of the first cantica,

brings the total number of cantos to 100. It is generally accepted,

however, that the first two cantos serve as a unitary prologue to the

entire epic, and that the opening two cantos of each cantica serve as prologues to each of the three cantiche.

The number three is prominent in the work (alluding to the Trinity), represented in part by the number of cantiche and their lengths. Additionally, the verse scheme used, terza rima, is hendecasyllabic (lines of eleven syllables), with the lines composing tercets according to the rhyme scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded, ...

Written in the first person, the poem tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300. The Roman poet Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory; Beatrice,

Dante's ideal woman, guides him through Heaven. Beatrice was a

Florentine woman he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the

mode of the then-fashionable courtly love tradition, which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova.

The structure of the three realms follows a common numerical pattern

of 9 plus 1, for a total of 10: 9 circles of the Inferno, followed by

Lucifer contained at its bottom; 9 rings of Mount Purgatory, followed by

the Garden of Eden crowning its summit; and the 9 celestial bodies of Paradiso, followed by the Empyrean

containing the very essence of God. Within each group of 9, 7 elements

correspond to a specific moral scheme, subdivided into three

subcategories, while 2 others of greater particularity are added to

total nine. For example, the seven deadly sins of the Catholic Church that are cleansed in Purgatory are joined by special realms for the late repentant and the excommunicated

by the church. The core seven sins within Purgatory correspond to a

moral scheme of love perverted, subdivided into three groups

corresponding to excessive love (Lust, Gluttony, Greed), deficient love (Sloth), and malicious love (Wrath, Envy, Pride).

In central Italy's political struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Dante was part of the Guelphs, who in general favored the Papacy over the Holy Roman Emperor.

Florence's Guelphs split into factions around 1300 – the White Guelphs

and the Black Guelphs. Dante was among the White Guelphs who were exiled

in 1302 by the Lord-Mayor Cante de' Gabrielli di Gubbio, after troops under Charles of Valois entered the city, at the request of Pope Boniface VIII, who supported the Black Guelphs. This exile, which lasted the rest of Dante's life, shows its influence in many parts of the Comedy, from prophecies of Dante's exile to Dante's views of politics, to the eternal damnation of some of his opponents.

The last word in each of the three cantiche is stelle ("stars").

Inferno

Gustave Doré's engravings illustrated the Divine Comedy (1861–1868); here Charon comes to ferry souls across the river Acheron to Hell.

The poem begins on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300, "halfway along our life's path" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita). Dante is thirty-five years old, half of the biblical lifespan of 70 (Psalms 89:10, Vulgate), lost in a dark wood (understood as sin), assailed by beasts (a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf) he cannot evade and unable to find the "straight way" (diritta via) –

also translatable as "right way" – to salvation (symbolized by the sun

behind the mountain). Conscious that he is ruining himself and that he

is falling into a "low place" (basso loco) where the sun is silent ('l sol tace), Dante is at last rescued by Virgil, and the two of them begin their journey to the underworld. Each sin's punishment in Inferno is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice; for example, in Canto XX, fortune-tellers and soothsayers must walk with their heads on backwards, unable to see what is ahead, because that was what they had tried to do in life:

they had their faces twisted toward their haunches

and found it necessary to walk backward,

because they could not see ahead of them.

... and since he wanted so to see ahead,

he looks behind and walks a backward path.

Allegorically, the Inferno represents the Christian soul

seeing sin for what it really is, and the three beasts represent three

types of sin: the self-indulgent, the violent, and the malicious.

These three types of sin also provide the three main divisions of

Dante's Hell: Upper Hell, outside the city of Dis, for the four sins of

indulgence (lust, gluttony, avarice, anger);

Circle 7 for the sins of violence; and Circles 8 and 9 for the sins of

fraud and treachery. Added to these are two unlike categories that are

specifically spiritual: Limbo, in Circle 1, contains the virtuous pagans

who were not sinful but were ignorant of Christ, and Circle 6 contains

the heretics who contradicted the doctrine and confused the spirit of

Christ. The circles number 9, with the addition of Satan completing the

structure of 9 + 1 = 10.

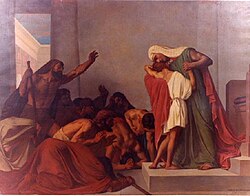

Purgatorio

Dante gazes at Mount Purgatory in an allegorical portrait by Agnolo Bronzino, painted c. 1530

Having survived the depths of Hell, Dante and Virgil ascend out of the undergloom to the Mountain of Purgatory on the far side of the world. The Mountain is on an island, the only land in the Southern Hemisphere, created by the displacement of rock which resulted when Satan's fall created Hell (which Dante portrays as existing underneath Jerusalem). The mountain has seven terraces, corresponding to the seven deadly sins or "seven roots of sinfulness." The classification of sin here is more psychological than that of the Inferno,

being based on motives, rather than actions. It is also drawn primarily

from Christian theology, rather than from classical sources.

However, Dante's illustrative examples of sin and virtue draw on

classical sources as well as on the Bible and on contemporary events.

Love, a theme throughout the Divine Comedy, is

particularly important for the framing of sin on the Mountain of

Purgatory. While the love that flows from God is pure, it can become

sinful as it flows through humanity. Humans can sin by using love

towards improper or malicious ends (Wrath, Envy, Pride), or using it to proper ends but with love that is either not strong enough (Sloth) or love that is too strong (Lust, Gluttony, Greed).

Below the seven purges of the soul is the Ante-Purgatory, containing

the Excommunicated from the church and the Late repentant who died,

often violently, before receiving rites. Thus the total comes to nine,

with the addition of the Garden of Eden at the summit, equaling ten.

Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the Christian life. Christian souls arrive escorted by an angel, singing In exitu Israel de Aegypto. In his Letter to Cangrande, Dante explains that this reference to Israel leaving Egypt refers both to the redemption of Christ and to "the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace." Appropriately, therefore, it is Easter Sunday when Dante and Virgil arrive.

The Purgatorio is notable for demonstrating the medieval knowledge of a spherical Earth. During the poem, Dante discusses the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. At this stage it is, Dante says, sunset at Jerusalem, midnight on the River Ganges, and sunrise in Purgatory.

Paradiso

Paradiso, Canto III: Dante and Beatrice speak to Piccarda and Constance of Sicily, in a fresco by Philipp Veit.

After an initial ascension, Beatrice guides Dante through the nine celestial spheres of Heaven. These are concentric and spherical, as in Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology. While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatorio were based on different classifications of sin, the structure of the Paradiso is based on the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues.

The seven lowest spheres of Heaven deal solely with the cardinal virtues of Prudence, Fortitude, Justice and Temperance. The first three spheres involve a deficiency of one of the cardinal virtues – the Moon, containing the inconstant, whose vows to God waned as the moon and thus lack fortitude; Mercury,

containing the ambitious, who were virtuous for glory and thus lacked

justice; and Venus, containing the lovers, whose love was directed

towards another than God and thus lacked Temperance. The final four

incidentally are positive examples of the cardinal virtues, all led on

by the Sun,

containing the prudent, whose wisdom lighted the way for the other

virtues, to which the others are bound (constituting a category on its

own). Mars contains the men of fortitude who died in the cause of Christianity; Jupiter contains the kings of Justice; and Saturn

contains the temperate, the monks who abided by the contemplative

lifestyle. The seven subdivided into three are raised further by two

more categories: the eighth sphere of the fixed stars that contain those

who achieved the theological virtues of faith, hope and love, and represent the Church Triumphant – the total perfection of humanity, cleansed of all the sins and carrying all the virtues of heaven; and the ninth circle, or Primum Mobile

(corresponding to the Geocentricism of Medieval astronomy), which

contains the angels, creatures never poisoned by original sin. Topping

them all is the Empyrean, which contains the essence of God, completing the 9-fold division to 10.

Dante meets and converses with several great saints of the Church, including Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Saint Peter, and St. John. The Paradiso is consequently more theological in nature than the Inferno and the Purgatorio.

However, Dante admits that the vision of heaven he receives is merely

the one his human eyes permit him to see, and thus the vision of heaven

found in the Cantos is Dante's personal vision.

The Divine Comedy finishes with Dante seeing the Triune God. In a flash of understanding that he cannot express, Dante finally understands the mystery of Christ's divinity and humanity, and his soul becomes aligned with God's love:

But already my desire and my will

were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed,

by the Love which moves the sun and the other stars.

History

Manuscripts

According to the Italian Dante Society, no original manuscript

written by Dante has survived, although there are many manuscript

copies from the 14th and 15th centuries – some 800 are listed on their

site.

Early printed editions

Title page of the first printed edition (Foligno, 11 April 1472)

First edition to name the poem Divina Comedia, 1555

Illustration of Lucifer in the first fully illustrated print edition. Woodcut for Inferno, canto 33. Pietro di Piasi, Venice, 1491.

The first printed edition was published in Foligno, Italy, by Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi on 11 April 1472. Of the 300 copies printed, fourteen still survive. The original printing press is on display in the Oratorio della Nunziatella in Foligno.

| Date | Title | Place | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1472 | La Comedia di Dante Alleghieri | Foligno | Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi | First printed edition (or editio princeps) |

| 1477 | La Commedia | Venice | Wendelin of Speyer |

|

| 1481 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Florence | Nicolaus Laurentii | With Cristoforo Landino's commentary in Italian, and some engraved illustrations by Baccio Baldini after designs by Sandro Botticelli |

| 1491 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Venice | Pietro di Piasi | First fully illustrated edition |

| 1502 | Le terze rime di Dante | Venice | Aldus Manutius |

|

| 1506 | Commedia di Dante insieme con uno diagolo circa el sito forma et misure dello inferno | Florence | Philippo di Giunta |

|

| 1555 | La Divina Comedia di Dante | Venice | Gabriel Giolito | First use of "Divine" in title |

Thematic concerns

The Divine Comedy can be described simply as an allegory:

each canto, and the episodes therein, can contain many alternative

meanings. Dante's allegory, however, is more complex, and, in explaining

how to read the poem – see the Letter to Cangrande – he outlines other levels of meaning besides the allegory: the historical, the moral, the literal, and the anagogical.

The structure of the poem is also quite complex, with

mathematical and numerological patterns distributed throughout the work,

particularly threes and nines, which are related to the Holy Trinity.

The poem is often lauded for its particularly human qualities: Dante's

skillful delineation of the characters he encounters in Hell, Purgatory,

and Paradise; his bitter denunciations of Florentine and Italian politics; and his powerful poetic imagination. Dante's use of real characters, according to Dorothy Sayers in her introduction to her translation of the Inferno,

allows Dante the freedom of not having to involve the reader in

description, and allows him to "[make] room in his poem for the

discussion of a great many subjects of the utmost importance, thus

widening its range and increasing its variety."

Dante called the poem "Comedy" (the adjective "Divine" was added

later, in the 16th century) because poems in the ancient world were

classified as High ("Tragedy") or Low ("Comedy").

Low poems had happy endings and were written in everyday language,

whereas High poems treated more serious matters and were written in an

elevated style. Dante was one of the first in the Middle Ages to write

of a serious subject, the Redemption of humanity, in the low and

"vulgar" Italian language and not the Latin one might expect for such a

serious topic. Boccaccio's account that an early version of the poem was begun by Dante in Latin is still controversial.

Scientific themes

Although the Divine Comedy is primarily a religious poem, discussing sin, virtue, and theology, Dante also discusses several elements of the science of his day (this mixture of science with poetry has received both praise and blame over the centuries). The Purgatorio repeatedly refers to the implications of a spherical Earth, such as the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. For example, at sunset in Purgatory it is midnight at the Ebro, dawn in Jerusalem, and noon on the River Ganges:

Just as, there where its Maker shed His blood,

the sun shed its first rays, and Ebro lay

beneath high Libra, and the ninth hour's rays

were scorching Ganges' waves; so here, the sun

stood at the point of day's departure when

God's angel – happy – showed himself to us.

Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity

in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120). A little earlier (XXXIII, 102–105), he

queries the existence of wind in the frozen inner circle of hell, since

it has no temperature differentials.

Inevitably, given its setting, the Paradiso discusses astronomy extensively, but in the Ptolemaic sense. The Paradiso also discusses the importance of the experimental method in science, with a detailed example in lines 94–105 of Canto II:

Yet an experiment, were you to try it,

could free you from your cavil and the source

of your arts' course springs from experiment.

Taking three mirrors, place a pair of them

at equal distance from you; set the third

midway between those two, but farther back.

Then, turning toward them, at your back have placed

a light that kindles those three mirrors and

returns to you, reflected by them all.

Although the image in the farthest glass

will be of lesser size, there you will see

that it must match the brightness of the rest.

A briefer example occurs in Canto XV of the Purgatorio (lines 16–21), where Dante points out that both theory and experiment confirm that the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. Other references to science in the Paradiso include descriptions of clockwork in Canto XXIV (lines 13–18), and Thales' theorem about triangles in Canto XIII (lines 101–102).

Galileo Galilei is known to have lectured on the Inferno, and it has been suggested that the poem may have influenced some of Galileo's own ideas regarding mechanics.

Theories of influence from Islamic philosophy

In 1919, Miguel Asín Palacios, a Spanish scholar and a Catholic priest, published La Escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia (Islamic Eschatology in the Divine Comedy), an account of parallels between early Islamic philosophy and the Divine Comedy. Palacios argued that Dante derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter from the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi and from the Isra and Mi'raj or night journey of Muhammad to heaven. The latter is described in the ahadith and the Kitab al Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before as Liber Scalae Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder"), and has significant similarities to the Paradiso, such as a sevenfold division of Paradise, although this is not unique to the Kitab al Miraj or Islamic cosmology.

Some "superficial similarities" of the Divine Comedy to the Resalat Al-Ghufran or Epistle of Forgiveness of Al-Ma'arri have also been mentioned in this debate. The Resalat Al-Ghufran

describes the journey of the poet in the realms of the afterlife and

includes dialogue with people in Heaven and Hell, although, unlike the Kitab al Miraj, there is little description of these locations, and it is unlikely that Dante borrowed from this work.

Dante did, however, live in a Europe of substantial literary and

philosophical contact with the Muslim world, encouraged by such factors

as Averroism

("Averrois, che'l gran comento feo" Commedia, Inferno, IV, 144, meaning

"Averrois, who wrote the great comment") and the patronage of Alfonso X of Castile. Of the twelve wise men Dante meets in Canto X of the Paradiso, Thomas Aquinas and, even more so, Siger of Brabant were strongly influenced by Arabic commentators on Aristotle. Medieval Christian mysticism also shared the Neoplatonic influence of Sufis such as Ibn Arabi. Philosopher Frederick Copleston argued in 1950 that Dante's respectful treatment of Averroes, Avicenna, and Siger of Brabant indicates his acknowledgement of a "considerable debt" to Islamic philosophy.

Although this philosophical influence is generally acknowledged,

many scholars have not been satisfied that Dante was influenced by the Kitab al Miraj. The 20th century Orientalist Francesco Gabrieli

expressed skepticism regarding the claimed similarities, and the lack

of evidence of a vehicle through which it could have been transmitted to

Dante. Even so, while dismissing the probability of some influences

posited in Palacios' work, Gabrieli conceded that it was "at least possible, if not probable, that Dante may have known the Liber Scalae and have taken from it certain images and concepts of Muslim eschatology". Shortly before her death, the Italian philologist Maria Corti pointed out that, during his stay at the court of Alfonso X, Dante's mentor Brunetto Latini met Bonaventura de Siena, a Tuscan who had translated the Kitab al Miraj from Arabic into Latin. Corti speculates that Brunetto may have provided a copy of that work to Dante. René Guénon, a Sufi convert and scholar of Ibn Arabi, rejected in The Esoterism of Dante the theory of his influence (direct or indirect) on Dante. Palacios' theory that Dante was influenced by Ibn Arabi was satirized by the Turkish academic Orhan Pamuk in his novel The Black Book.

Literary influence in the English-speaking world and beyond

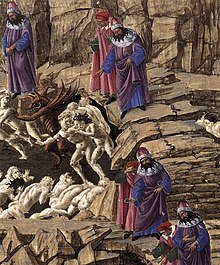

A detail from one of Sandro Botticelli's illustrations for Inferno, Canto XVIII, 1480s. Silverpoint on parchment, completed in pen and ink.

The Divine Comedy was not always as well-regarded as it is today. Although recognized as a masterpiece in the centuries immediately following its publication, the work was largely ignored during the Enlightenment, with some notable exceptions such as Vittorio Alfieri; Antoine de Rivarol, who translated the Inferno into French; and Giambattista Vico, who in the Scienza nuova and in the Giudizio su Dante inaugurated what would later become the romantic reappraisal of Dante, juxtaposing him to Homer. The Comedy was "rediscovered" in the English-speaking world by William Blake – who illustrated several passages of the epic – and the Romantic writers of the 19th century. Later authors such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, C. S. Lewis and James Joyce have drawn on it for inspiration. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was its first American translator, and modern poets, including Seamus Heaney, Robert Pinsky, John Ciardi, W. S. Merwin, and Stanley Lombardo, have also produced translations of all or parts of the book. In Russia, beyond Pushkin's translation of a few tercets, Osip Mandelstam's late poetry has been said to bear the mark of a "tormented meditation" on the Comedy. In 1934, Mandelstam gave a modern reading of the poem in his labyrinthine "Conversation on Dante". In T. S. Eliot's estimation, "Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third." For Jorge Luis Borges the Divine Comedy was "the best book literature has achieved".

English translations

New English translations of the Divine Comedy continue to be published regularly. Notable English translations of the complete poem include the following.

| Year | Translator | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1805–1814 | Henry Francis Cary | An older translation, widely available online. |

| 1867 | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Unrhymed terzines. The first U.S. translation, raising American interest in the poem. It is still widely available, including online. |

| 1891–1892 | Charles Eliot Norton | Prose translation used by Great Books of the Western World. Available online at Project Gutenberg. |

| 1933–1943 | Laurence Binyon | Terza rima. Translated with assistance from Ezra Pound |

| 1949–1962 | Dorothy L. Sayers | Translated for Penguin Classics, intended for a wider audience, and completed by Barbara Reynolds. |

| 1969 | Thomas G. Bergin | Cast in blank verse with illustrations by Leonard Baskin.[65] |

| 1954–1970 | John Ciardi | His Inferno was recorded and released by Folkways Records in 1954. |

| 1970–1991 | Charles S. Singleton | Literal prose version with extensive commentary; 6 vols. |

| 1981 | C. H. Sisson | Available in Oxford World's Classics. |

| 1980–1984 | Allen Mandelbaum | Available online. |

| 1967–2002 | Mark Musa | An alternative Penguin Classics version. |

| 2000–2007 | Robert and Jean Hollander | Online as part of the Princeton Dante Project. |

| 2002–2004 | Anthony M. Esolen | Modern Library Classics edition. |

| 2006–2007 | Robin Kirkpatrick | A third Penguin Classics version, replacing Musa's. |

| 2010 | Burton Raffel | A Northwestern World Classics version. |

| 2013 | Clive James | A poetic version in quatrains. |

A number of other translators, such as Robert Pinsky, have translated the Inferno only.

In the arts

Dante and Virgil in Hell, painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1850)

The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for

countless artists for almost seven centuries. There are many references

to Dante's work in literature. In music, Franz Liszt was one of many composers to write works based on the Divine Comedy. In sculpture, the work of Auguste Rodin includes themes from Dante, and many visual artists have illustrated Dante's work, as shown by the examples above. There have also been many references to the Divine Comedy in cinema, television, digital arts, comics and video games.