Background radiation is a measure of the level of ionizing radiation present in the environment at a particular location which is not due to deliberate introduction of radiation sources.

Background radiation originates from a variety of sources, both natural and artificial. These include both cosmic radiation and environmental radioactivity from naturally occurring radioactive materials (such as radon and radium), as well as man-made medical X-rays, fallout from nuclear weapons testing and nuclear accidents.

Background radiation originates from a variety of sources, both natural and artificial. These include both cosmic radiation and environmental radioactivity from naturally occurring radioactive materials (such as radon and radium), as well as man-made medical X-rays, fallout from nuclear weapons testing and nuclear accidents.

Definition

Background radiation is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency

as "Dose or dose rate (or an observed measure related to the dose or

dose rate) attributable to all sources other than the one(s) specified.

So a distinction is made between dose which is already in a location,

which is defined here as being "background", and the dose due to a

deliberately introduced and specified source. This is important where

radiation measurements are taken of a specified radiation source, where

the existing background may affect this measurement. An example would be

measurement of radioactive contamination in a gamma radiation

background, which could increase the total reading above that expected

from the contamination alone.

However, if no radiation source is specified as being of concern,

then the total radiation dose measurement at a location is generally

called the background radiation, and this is usually the case where an ambient dose rate is measured for environmental purposes.

Background dose rate examples

Background radiation varies with location and time, and the following table gives examples:

| Radiation source | World | US | Japan | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhalation of air | 1.26 | 2.28 | 0.40 | mainly from radon, depends on indoor accumulation |

| Ingestion of food & water | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.40 | (K-40, C-14, etc.) |

| Terrestrial radiation from ground | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.40 | depends on soil and building material |

| Cosmic radiation from space | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.30 | depends on altitude |

| sub total (natural) | 2.40 | 3.10 | 1.50 | sizeable population groups receive 10–20 mSv |

| Medical | 0.60 | 3.00 | 2.30 | worldwide figure excludes radiotherapy; US figure is mostly CT scans and nuclear medicine. |

| Consumer items | – | 0.13 | cigarettes, air travel, building materials, etc. | |

| Atmospheric nuclear testing | 0.005 | – | 0.01 | peak of 0.11 mSv in 1963 and declining since; higher near sites |

| Occupational exposure | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.01 | worldwide average to workers only is 0.7 mSv, mostly due to radon in mines; US is mostly due to medical and aviation workers. |

| Chernobyl accident | 0.002 | – | 0.01 | peak of 0.04 mSv in 1986 and declining since; higher near site |

| Nuclear fuel cycle | 0.0002 | 0.001 | up to 0.02 mSv near sites; excludes occupational exposure | |

| Other | – | 0.003 | Industrial, security, medical, educational, and research | |

| sub total (artificial) | 0.61 | 3.14 | 2.33 |

|

| Total | 3.01 | 6.24 | 3.83 | millisieverts per year |

Natural background radiation

The weather station outside of the Atomic Testing Museum on a hot summer day. Displayed background gamma radiation level is 9.8 μR/h (0.82 mSv/a) This is very close to the world average background radiation of 0.87 mSv/a from cosmic and terrestrial sources.

Cloud chambers

used by early researchers first detected cosmic rays and other

background radiation. They can be used to visualize the background

radiation

Radioactive material is found throughout nature. Detectable amounts occur naturally in soil, rocks, water, air, and vegetation, from which it is inhaled and ingested into the body. In addition to this internal exposure, humans also receive external exposure from radioactive materials that remain outside the body and from cosmic radiation from space. The worldwide average natural dose to humans is about 2.4 mSv (240 mrem) per year. This is four times the worldwide average artificial radiation exposure, which in 2008 amounted to about 0.6 millisieverts (60 mrem)

per year. In some rich countries, like the US and Japan, artificial

exposure is, on average, greater than the natural exposure, due to

greater access to medical imaging.

In Europe, average natural background exposure by country ranges from

under 2 mSv (200 mrem) annually in the United Kingdom to more than 7 mSv

(700 mrem) annually for some groups of people in Finland.

The International Atomic Energy Agency states:

- "Exposure to radiation from natural sources is an inescapable

feature of everyday life in both working and public environments. This

exposure is in most cases of little or no concern to society, but in

certain situations the introduction of health protection measures needs

to be considered, for example when working with uranium and thorium ores

and other Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM). These situations have become the focus of greater attention by the Agency in recent years."

Terrestrial sources

Terrestrial radiation, for the purpose of the table above, only includes sources that remain external to the body. The major radionuclides of concern are potassium, uranium and thorium and their decay products, some of which, like radium and radon are intensely radioactive but occur in low concentrations. Most of these sources have been decreasing, due to radioactive decay

since the formation of the Earth, because there is no significant

amount currently transported to the Earth. Thus, the present activity on

earth from uranium-238 is only half as much as it originally was because of its 4.5 billion year half-life, and potassium-40

(half-life 1.25 billion years) is only at about 8% of original

activity. But during the time that humans have existed the amount of

radiation has decreased very little.

Many shorter half-life (and thus more intensely radioactive)

isotopes have not decayed out of the terrestrial environment because of

their on-going natural production. Examples of these are radium-226 (decay product of thorium-230 in decay chain of uranium-238) and radon-222 (a decay product of radium-226 in said chain).

Thorium and uranium (and their daughters) primarily undergo alpha and beta decay, and aren't easily detectable. However, many of their daughter products are strong gamma emitters. Thorium-232 is detectable via a 239 keV peak from lead-212, 511, 583 and 2614 keV from thallium-208, and 911 and 969 keV from actinium-228. Uranium-238 manifests as 609, 1120, and 1764 keV peaks of bismuth-214 (cf. the same peak for atmospheric radon). Potassium-40 is detectable directly via its 1461 keV gamma peak.

The level over the sea and other large bodies of water tends to

be about a tenth of the terrestrial background. Conversely, coastal

areas (and areas by the side of fresh water) may have an additional

contribution from dispersed sediment.

Airborne sources

The biggest source of natural background radiation is airborne radon, a radioactive gas that emanates from the ground. Radon and its isotopes, parent radionuclides, and decay products all contribute to an average inhaled dose of 1.26 mSv/a (millisievert per year).

Radon is unevenly distributed and varies with weather, such that much

higher doses apply to many areas of the world, where it represents a significant health hazard.

Concentrations over 500 times the world average have been found inside

buildings in Scandinavia, the United States, Iran, and the Czech

Republic.

Radon is a decay product of uranium, which is relatively common in the

Earth's crust, but more concentrated in ore-bearing rocks scattered

around the world. Radon seeps out of these ores into the atmosphere or into ground water or infiltrates into buildings. It can be inhaled into the lungs, along with its decay products, where they will reside for a period of time after exposure.

Although radon is naturally occurring, exposure can be enhanced

or diminished by human activity, notably house construction. A poorly

sealed basement in an otherwise well insulated house can result in the

accumulation of radon within the dwelling, exposing its residents to

high concentrations. The widespread construction of well insulated and

sealed homes in the northern industrialized world has led to radon

becoming the primary source of background radiation in some localities

in northern North America and Europe. Basement sealing and suction ventilation reduce exposure. Some building materials, for example lightweight concrete with alum shale, phosphogypsum and Italian tuff, may emanate radon if they contain radium and are porous to gas.

Radiation exposure from radon is indirect. Radon has a short half-life (4 days) and decays into other solid particulate radium-series

radioactive nuclides. These radioactive particles are inhaled and

remain lodged in the lungs, causing continued exposure. Radon is thus

assumed to be the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, and accounts for 15,000 to 22,000 cancer deaths per year in the US alone. However, the discussion about the opposite experimental results is still going on.

About 100,000 Bq/m3 of radon was found in Stanley Watras's basement in 1984. He and his neighbours in Boyertown, Pennsylvania,

United States may hold the record for the most radioactive dwellings in

the world. International radiation protection organizations estimate

that a committed dose may be calculated by multiplying the equilibrium equivalent concentration (EEC) of radon by a factor of 8 to 9 nSv·m3/Bq·h and the EEC of thoron by a factor of 40 nSv·m3/Bq·h.

Most of the atmospheric background is caused by radon and its decay products. The gamma spectrum shows prominent peaks at 609, 1120, and 1764 keV, belonging to bismuth-214,

a radon decay product. The atmospheric background varies greatly with

wind direction and meteorological conditions. Radon also can be released

from the ground in bursts and then form "radon clouds" capable of

traveling tens of kilometers.

Cosmic radiation

Estimate

of the maximum dose of radiation received at an altitude of 12 km 20

January 2005, following a violent solar flare. The doses are expressed

in microsieverts per hour.

The Earth and all living things on it are constantly bombarded by

radiation from outer space. This radiation primarily consists of

positively charged ions from protons to iron and larger nuclei derived from outside the Solar System. This radiation interacts with atoms in the atmosphere to create an air shower of secondary radiation, including X-rays, muons, protons, alpha particles, pions, electrons, and neutrons.

The immediate dose from cosmic radiation is largely from muons,

neutrons, and electrons, and this dose varies in different parts of the

world based largely on the geomagnetic field and altitude. For example, the city of Denver in the United States (at 1650 meters elevation) receives a cosmic ray dose roughly twice that of a location at sea level. This radiation is much more intense in the upper troposphere, around 10 km altitude, and is thus of particular concern for airline

crews and frequent passengers, who spend many hours per year in this

environment. During their flights airline crews typically get an

additional occupational dose between 2.2 mSv (220 mrem) per year and 2.19 mSv/year, according to various studies.

Similarly, cosmic rays cause higher background exposure in astronauts than in humans on the surface of Earth. Astronauts in low orbits, such as in the International Space Station or the Space Shuttle, are partially shielded by the magnetic field of the Earth, but also suffer from the Van Allen radiation belt which accumulates cosmic rays and results from the Earth's magnetic field. Outside low Earth orbit, as experienced by the Apollo astronauts who traveled to the Moon,

this background radiation is much more intense, and represents a

considerable obstacle to potential future long term human exploration of

the moon or Mars.

Cosmic rays also cause elemental transmutation in the atmosphere, in which secondary radiation generated by the cosmic rays combines with atomic nuclei in the atmosphere to generate different nuclides. Many so-called cosmogenic nuclides can be produced, but probably the most notable is carbon-14, which is produced by interactions with nitrogen

atoms. These cosmogenic nuclides eventually reach the Earth's surface

and can be incorporated into living organisms. The production of these

nuclides varies slightly with short-term variations in solar cosmic ray

flux, but is considered practically constant over long scales of

thousands to millions of years. The constant production, incorporation

into organisms and relatively short half-life of carbon-14 are the principles used in radiocarbon dating of ancient biological materials, such as wooden artifacts or human remains.

The cosmic radiation at sea level usually manifests as 511 keV gamma rays from annihilation of positrons

created by nuclear reactions of high energy particles and gamma rays.

At higher altitudes there is also the contribution of continuous bremsstrahlung spectrum.

Food and water

Two

of the essential elements that make up the human body, namely potassium

and carbon, have radioactive isotopes that add significantly to our

background radiation dose. An average human contains about 17 milligrams

of potassium-40 (40K) and about 24 nanograms (10−9 g) of carbon-14 (14C),

(half-life 5,730 years). Excluding internal contamination by external

radioactive material, these two are largest components of internal

radiation exposure from biologically functional components of the human

body. About 4,000 nuclei of 40K decay per second, and a similar number of 14C. The energy of beta particles produced by 40K is about 10 times that from the beta particles from 14C decay.

14C is present in the human body at a level of about 3700 Bq (0.1 μCi) with a biological half-life of 40 days. This means there are about 3700 beta particles per second produced by the decay of 14C. However, a 14C atom is in the genetic information of about half the cells, while potassium is not a component of DNA. The decay of a 14C atom inside DNA in one person happens about 50 times per second, changing a carbon atom to one of nitrogen.

The global average internal dose from radionuclides other than

radon and its decay products is 0.29 mSv/a, of which 0.17 mSv/a comes

from 40K, 0.12 mSv/a comes from the uranium and thorium series, and 12 μSv/a comes from 14C.

Areas with high natural background radiation

Some areas have greater dosage than the country-wide averages. In the world in general, exceptionally high natural background locales include Ramsar in Iran, Guarapari in Brazil, Karunagappalli in India, Arkaroola in Australia, and Yangjiang in China.

The highest level of purely natural radiation ever recorded on the Earth's surface was 90 µGy/h on a Brazilian black beach (areia preta in Portuguese) composed of monazite.

This rate would convert to 0.8 Gy/a for year-round continuous exposure,

but in fact the levels vary seasonally and are much lower in the

nearest residences. The record measurement has not been duplicated and

is omitted from UNSCEAR's latest reports. Nearby tourist beaches in Guarapari and Cumuruxatiba were later evaluated at 14 and 15 µGy/h. Note that the values quoted here are in Grays.

To convert to Sieverts (Sv) a radiation weighting factor is required;

these weighting factors vary from 1 (beta & gamma) to 20 (alpha

particles).

The highest background radiation in an inhabited area is found in Ramsar,

primarily due to the use of local naturally radioactive limestone as a

building material. The 1000 most exposed residents receive an average

external effective radiation dose of 6 mSv (600 mrem) per year, six times the ICRP recommended limit for exposure to the public from artificial sources.

They additionally receive a substantial internal dose from radon.

Record radiation levels were found in a house where the effective dose

due to ambient radiation fields was 131 mSv (13.1 rem) per year, and the

internal committed dose from radon was 72 mSv (7.2 rem) per year. This unique case is over 80 times higher than the world average natural human exposure to radiation.

Epidemiological studies are underway to identify health effects

associated with the high radiation levels in Ramsar. It is much too

early to draw unambiguous statistically significant conclusions. While so far support for beneficial effects of chronic radiation (like longer lifespan) has been observed in few places only,

a protective and adaptive effect is suggested by at least one study

whose authors nonetheless caution that data from Ramsar are not yet

sufficiently strong to relax existing regulatory dose limits.

However, the recent statistical analyses discussed that there is no

correlation between the risk of negative health effects and elevated

level of natural background radiation.

Photoelectric

Background

radiation doses in the immediate vicinity of particles of high atomic

number materials, within the human body, have a small enhancement due to

the photoelectric effect.

Neutron background

Most

of the natural neutron background is a product of cosmic rays

interacting with the atmosphere. The neutron energy peaks at around

1 MeV and rapidly drops above. At sea level, the production of neutrons

is about 20 neutrons per second per kilogram of material interacting

with the cosmic rays (or, about 100–300 neutrons per square meter per

second). The flux is dependent on geomagnetic latitude, with a maximum

near the magnetic poles. At solar minimums, due to lower solar magnetic

field shielding, the flux is about twice as high vs the solar maximum.

It also dramatically increases during solar flares. In the vicinity of

larger heavier objects, e.g. buildings or ships, the neutron flux

measures higher; this is known as "cosmic ray induced neutron

signature", or "ship effect" as it was first detected with ships at sea.

Artificial background radiation

Displays

showing ambient radiation fields of 0.120–0.130 μSv/h (1.05–1.14 mSv/a)

in a nuclear power plant. This reading includes natural background from

cosmic and terrestrial sources.

Atmospheric nuclear testing

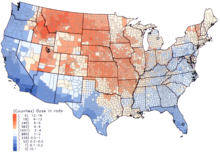

Per capita thyroid doses in the continental United States resulting from all exposure routes from all atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site from 1951–1962.

Atmospheric 14C, New Zealand and Austria.

The New Zealand curve is representative for the Southern Hemisphere,

the Austrian curve is representative for the Northern Hemisphere.

Atmospheric nuclear weapon tests almost doubled the concentration of 14C in the Northern Hemisphere.

Frequent above-ground nuclear explosions between the 1940s and 1960s scattered a substantial amount of radioactive contamination.

Some of this contamination is local, rendering the immediate

surroundings highly radioactive, while some of it is carried longer

distances as nuclear fallout;

some of this material is dispersed worldwide. The increase in

background radiation due to these tests peaked in 1963 at about 0.15 mSv

per year worldwide, or about 7% of average background dose from all

sources. The Limited Test Ban Treaty

of 1963 prohibited above-ground tests, thus by the year 2000 the

worldwide dose from these tests has decreased to only 0.005 mSv per

year.

Occupational exposure

The International Commission on Radiological Protection recommends limiting occupational radiation exposure to 50 mSv (5 rem) per year, and 100 mSv (10 rem) in 5 years.

However, background radiation for occupational doses

includes radiation that is not measured by radiation dose instruments in

potential occupational exposure conditions. This includes both offsite

"natural background radiation" and any medical radiation doses. This

value is not typically measured or known from surveys, such that

variations in the total dose to individual workers is not known. This

can be a significant confounding factor in assessing radiation exposure

effects in a population of workers who may have significantly different

natural background and medical radiation doses. This is most significant

when the occupational doses are very low.

At an IAEA conference in 2002, it was recommended that occupational doses below 1–2 mSv per year do not warrant regulatory scrutiny.

Nuclear accidents

Under

normal circumstances, nuclear reactors release small amounts of

radioactive gases, which cause small radiation exposures to the public.

Events classified on the International Nuclear Event Scale

as incidents typically do not release any additional radioactive

substances into the environment. Large releases of radioactivity from

nuclear reactors are extremely rare. To the present day, there were two

major civilian accidents – the Chernobyl accident and the Fukushima I nuclear accidents – which caused substantial contamination [DJS -- What is "substantial"?]. The Chernobyl accident was the only one to cause immediate deaths.

Total doses from the Chernobyl accident ranged from 10 to 50 mSv

over 20 years for the inhabitants of the affected areas, with most of

the dose received in the first years after the disaster, and over 100

mSv for liquidators. There were 28 deaths from acute radiation syndrome.

Total doses from the Fukushima I accidents were between 1 and 15

mSv for the inhabitants of the affected areas. Thyroid doses for

children were below 50 mSv. 167 cleanup workers received doses above 100

mSv, with 6 of them receiving more than 250 mSv (the Japanese exposure

limit for emergency response workers).

The average dose from the Three Mile Island accident was 0.01 mSv.

Non-civilian: In addition to the civilian accidents described above, several accidents at early nuclear weapons facilities – such as the Windscale fire, the contamination of the Techa River by the nuclear waste from the Mayak compound, and the Kyshtym disaster

at the same compound – released substantial radioactivity into the

environment. The Windscale fire resulted in thyroid doses of 5–20 mSv

for adults and 10–60 mSv for children. The doses from the accidents at Mayak are unknown.

Nuclear fuel cycle

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the United States Environmental Protection Agency,

and other U.S. and international agencies, require that licensees limit

radiation exposure to individual members of the public to 1 mSv (100 mrem) per year.

Other

Coal plants emit radiation in the form of radioactive fly ash which is inhaled and ingested by neighbours, and incorporated into crops. A 1978 paper from Oak Ridge National Laboratory

estimated that coal-fired power plants of that time may contribute a

whole-body committed dose of 19 µSv/a to their immediate neighbours in a

radius of 500 m. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation's

1988 report estimated the committed dose 1 km away to be 20 µSv/a for

older plants or 1 µSv/a for newer plants with improved fly ash capture,

but was unable to confirm these numbers by test.

When coal is burned, uranium, thorium and all the uranium daughters

accumulated by disintegration — radium, radon, polonium — are released.

Radioactive materials previously buried underground in coal deposits

are released as fly ash or, if fly ash is captured, may be incorporated

into concrete manufactured with fly ash.

Other sources of dose uptake

Medical

The global average human exposure to artificial radiation is 0.6 mSv/a, primarily from medical imaging. This medical component can range much higher, with an average of 3 mSv per year across the USA population.

Other human contributors include smoking, air travel, radioactive

building materials, historical nuclear weapons testing, nuclear power

accidents and nuclear industry operation.

A typical chest x-ray delivers 20 µSv (2 mrem) of effective dose. A dental x-ray delivers a dose of 5 to 10 µSv. A CT scan

delivers an effective dose to the whole body ranging from 1 to 20 mSv

(100 to 2000 mrem). The average American receives about 3 mSv of

diagnostic medical dose per year; countries with the lowest levels of

health care receive almost none. Radiation treatment for various

diseases also accounts for some dose, both in individuals and in those

around them.

Consumer items

Cigarettes contain polonium-210, originating from the decay products of radon, which stick to tobacco leaves.

Heavy smoking results in a radiation dose of 160 mSv/year to localized

spots at the bifurcations of segmental bronchi in the lungs from the

decay of polonium-210. This dose is not readily comparable to the

radiation protection limits, since the latter deal with whole body

doses, while the dose from smoking is delivered to a very small portion

of the body.

Radiation metrology

In a radiation metrology laboratory, background radiation

refers to the measured value from any incidental sources that affect an

instrument when a specific radiation source sample is being measured.

This background contribution, which is established as a stable value by

multiple measurements, usually before and after sample measurement, is

subtracted from the rate measured when the sample is being measured.

This is in accordance with the International Atomic Energy Agency

definition of background as being "Dose or dose rate (or an observed

measure related to the dose or dose rate) attributable to all sources

other than the one(s) specified.

The same issue occurs with radiation protection instruments,

where a reading from an instrument may be affected by the background

radiation. An example of this is a scintillation detector

used for surface contamination monitoring. In an elevated gamma

background the scintillator material will be affected by the background

gamma, which will add to the reading obtained from any contamination

which is being monitored. In extreme cases it will make the instrument

unusable as the background swamps the lower level of radiation from the

contamination. In such instruments the background can be continually

monitored in the "Ready" state, and subtracted from any reading obtained

when being used in "Measuring" mode.

Regular Radiation measurement is carried out at multiple levels.

Government agencies compile radiation readings as part of environmental

monitoring mandates, often making the readings available to the public

and sometimes in near-real-time. Collaborative groups and private

individuals may also make real-time readings available to the public.

Instruments used for radiation measurement include the Geiger–Müller tube and the Scintillation detector.

The former is usually more compact and affordable and reacts to

several radiation types, while the latter is more complex and can detect

specific radiation energies and types. Readings indicate radiation

levels from all sources including background, and real-time readings are

in general unvalidated, but correlation between independent detectors

increases confidence in measured levels.

List of near-real-time government radiation measurement sites, employing multiple instrument types:

- Europe and Canada: European Radiological Data Exchange Platform (EURDEP) Simple map of Gamma Dose Rates

- USA: EPA Radnet near-real-time and laboratory data by state

List of international near-real-time collaborative/private measurement sites, employing primarily Geiger-Muller detectors:

- GMC map: http://www.gmcmap.com/ (mix of old-data detector stations and some near-real-time ones)

- Netc: http://www.netc.com/

- Radmon: http://www.radmon.org/

- Radiation Network: http://radiationnetwork.com/

- Radioactive@Home: http://radioactiveathome.org/map/

- Safecast: http://safecast.org/tilemap (the green circles are real-time detectors)

- uRad Monitor: http://www.uradmonitor.com/