Progressivism is a political philosophy and reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century. Middle class and reformist in nature, it arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization such as the growth of large corporations, pollution and rampant corruption in American politics. In the 21st century, progressives continue to embrace concepts such as environmentalism and social justice. While the modern progressive movement may be characterized as largely secular in nature, by comparison, the historical progressive movement was to a significant extent rooted in and energized by religion.

Historian Alonzo Hamby defined American progressivism as the "political movement that addresses ideas, impulses, and issues stemming from modernization of American society. Emerging at the end of the nineteenth century, it established much of the tone of American politics throughout the first half of the century".

Progressive Era

Historians debate the exact contours, but generally date the "Progressive Era" from the 1890s to either World War I or the onset of the Great Depression, in response to the excesses of the Gilded Age.

Many of the core principles of the Progressive Movement focused

on the need for efficiency in all areas of society. Purification to

eliminate waste and corruption was a powerful element,

as well as the Progressives' support of worker compensation, improved

child labor laws, minimum wage legislation, a support for a maximum

hours that workers could work for, graduated income tax and allowed

women the right to vote.

According to historian William Leuchtenburg:

The Progressives believed in the Hamiltonian concept of positive government, of a national government directing the destinies of the nation at home and abroad. They had little but contempt for the strict construction of the Constitution by conservative judges, who would restrict the power of the national government to act against social evils and to extend the blessings of democracy to less favored lands. The real enemy was particularism, state rights, limited government.

Purifying the electorate

Progressives

repeatedly warned that illegal voting was corrupting the political

system. They especially identified big-city bosses, working with saloon

keepers and precinct workers, as the culprits who stuffed the ballot

boxes. The solution to purifying the vote included prohibition (designed

to close down the saloons), voter registration requirements (designed

to end multiple voting), and literacy tests (designed to minimize the

number of ignorant voters).

All of the Southern states (and Oklahoma) used devices to disenfranchise black voters during the Progressive Era.

Typically the progressive elements in those states pushed for

disenfranchisement, often fighting against the conservatism of the Black

Belt whites.

A major reason given was that whites routinely purchased black votes to

control elections, and it was easier to disenfranchise blacks than to

go after powerful white men.

In the North, Progressives such as William U'Ren and Robert La Follette argued that the average citizen should have more control over his government. The Oregon System of "Initiative, Referendum, and Recall" was exported to many states, including Idaho, Washington, and Wisconsin. Many progressives, such as George M. Forbes, president of Rochester's

Board of Education, hoped to make government in the U.S. more

responsive to the direct voice of the American people when he said:

[W]e are now intensely occupied in forging the tools of democracy, the direct primary, the initiative, the referendum, the recall, the short ballot, commission government. But in our enthusiasm we do not seem to be aware that these tools will be worthless unless they are used by those who are aflame with the sense of brotherhood ... The idea [of the social centers movement is] to establish in each community an institution having a direct and vital relation to the welfare of the neighborhood, ward, or district, and also to the city as a whole.

Philip J. Ethington seconds this high view of direct democracy saying:

initiatives, referendums, and recalls, along with direct primaries and the direct election of US Senators, were the core achievements of 'direct democracy' by the Progressive generation during the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Women marching for the right to vote, 1912

Progressives fought for women's suffrage to purify the elections using supposedly purer female voters.

Progressives in the South supported the elimination of supposedly

corrupt black voters from the election booth. Historian Michael Perman

says that in both Texas and Georgia, "disfranchisement was the weapon as

well as the rallying cry in the fight for reform"; and in Virginia,

"the drive for disfranchisement had been initiated by men who saw

themselves as reformers, even progressives."

While the ultimate significance of the progressive movement on today's politics is still up for debate, Alonzo L. Hamby asks:

What were the central themes that emerged from the cacophony [of progressivism]? Democracy or elitism? Social justice or social control? Small entrepreneurship or concentrated capitalism? And what was the impact of American foreign policy? Were the progressives isolationists or interventionists? Imperialists or advocates of national self-determination? And whatever they were, what was their motivation? Moralistic utopianism? Muddled relativistic pragmatism? Hegemonic capitalism? Not surprisingly many battered scholars began to shout 'no mas!' In 1970, Peter Filene declared that the term 'progressivism' had become meaningless.

Municipal administration

The

Progressives typically concentrated on city and state government,

looking for waste and better ways to provide services as the cities grew

rapidly. These changes led to a more structured system, power that had

been centralized within the legislature would now be more locally

focused. The changes were made to the system to effectively make legal

processes, market transactions, bureaucratic administration, and

democracy easier to manage, thus putting them under the classification

of "Municipal Administration". There was also a change in authority for

this system; it was believed that the authority that was not properly

organized had now given authority to professionals, experts, and

bureaucrats for these services. These changes led to a more solid type

of municipal administration compared to the old system that was

underdeveloped and poorly constructed.

The Progressives mobilized concerned middle class voters, as well

as newspapers and magazines, to identify problems and concentrate

reform sentiment on specific problems. Many Protestants focused on the

saloon as the power base for corruption, as well as violence and family

disruption, so they tried to get rid of the entire saloon system through

prohibition. Others (like Jane Addams in Chicago) promoted Settlement Houses. Early municipal reformers included Hazen S. Pingree (mayor of Detroit in the 1890s) and Tom L. Johnson

in Cleveland, Ohio. In 1901, Johnson won election as mayor of Cleveland

on a platform of just taxation, home rule for Ohio cities, and a 3-cent

streetcar fare. Columbia University President Seth Low was elected mayor of New York City in 1901 on a reform ticket.

Efficiency

Many progressives such as Louis Brandeis

hoped to make American governments better able to serve the people's

needs by making governmental operations and services more efficient and

rational. Rather than making legal arguments against ten-hour workdays

for women, he used "scientific principles" and data produced by social

scientists documenting the high costs of long working hours for both

individuals and society.

The progressives' quest for efficiency was sometimes at odds with the

progressives' quest for democracy. Taking power out of the hands of

elected officials and placing that power in the hands of professional

administrators reduced the voice of the politicians and in turn reduced

the voice of the people. Centralized decision-making by trained experts

and reduced power for local wards made government less corrupt but more

distant and isolated from the people it served. Progressives who

emphasized the need for efficiency typically argued that trained

independent experts could make better decisions than the local

politicians. Thus Walter Lippmann in his influential Drift and Mastery

(1914), stressing the "scientific spirit" and "discipline of

democracy," called for a strong central government guided by experts

rather than public opinion.

One example of progressive reform was the rise of the city manager

system, in which paid, professional engineers ran the day-to-day

affairs of city governments under guidelines established by elected city councils.

Many cities created municipal "reference bureaus" which did expert

surveys of government departments looking for waste and inefficiency.

After in-depth surveys, local and even state governments were

reorganized to reduce the number of officials and to eliminate

overlapping areas of authority between departments. City governments

were reorganized to reduce the power of local ward bosses and to

increase the powers of the city council. Governments at every level

began developing budgets to help them plan their expenditures (rather

than spending money haphazardly as needs arose and revenue became

available). Governor Frank Lowden of Illinois showed a "passion for efficiency" as he streamlined state government.

Governmental corruption

Corruption represented a source of waste and inefficiency in the government. William U'Ren in Oregon, and Robert M. La Follette Sr. in Wisconsin, and others worked to clean up state and local governments by passing laws to weaken the power of machine politicians and political bosses. In Wisconsin, La Follette pushed through an open primary system that stripped party bosses of the power to pick party candidates.

The Oregon System, which included a "Corrupt Practices Act", a public

referendum, and a state-funded voter's pamphlet among other reforms was

exported to other states in the northwest and Midwest. Its high point

was in 1912, after which they detoured into a disastrous third party

status.

Education

Early progressive thinkers such as John Dewey and Lester Ward

placed a universal and comprehensive system of education at the top of

the progressive agenda, reasoning that if a democracy were to be

successful, its leaders, the general public, needed a good education.

Progressives worked hard to expand and improve public and private

education at all levels. Modernization of society, they believed,

necessitated the compulsory education of all children, even if the

parents objected. Progressives turned to educational researchers to

evaluate the reform agenda by measuring numerous aspects of education,

later leading to standardized testing.

Many educational reforms and innovations generated during this period

continued to influence debates and initiatives in American education for

the remainder of the 20th century. One of the most apparent legacies of

the Progressive Era left to American education was the perennial drive

to reform schools and curricula, often as the product of energetic

grass-roots movements in the city.

Since progressivism was and continues to be 'in the eyes of the

beholder,' progressive education encompasses very diverse and sometimes

conflicting directions in educational policy. Such enduring legacies of

the Progressive Era continue to interest historians. Progressive Era

reformers stressed 'object teaching,' meeting the needs of particular

constituencies within the school district, equal educational opportunity

for boys and girls, and avoiding corporal punishment.

Gamson (2003) examines the implementation of progressive reforms in three city school districts—Seattle, Washington, Oakland, California, and Denver, Colorado—during

1900–28. Historians of educational reform during the Progressive Era

tend to highlight the fact that many progressive policies and reforms

were very different and, at times, even contradictory. At the school

district level, contradictory reform policies were often especially

apparent, though there is little evidence of confusion among progressive

school leaders in Seattle, Oakland, and Denver. District leaders in

these cities, including Frank B. Cooper

in Seattle and Fred M. Hunter in Oakland, often employed a seemingly

contradictory set of reforms: local progressive educators consciously

sought to operate independently of national progressive movements; they

preferred reforms that were easy to implement; and they were encouraged

to mix and blend diverse reforms that had been shown to work in other

cities.

The reformers emphasized professionalization and

bureaucratization. The old system whereby ward politicians selected

school employees was dropped in the case of teachers and replaced by a

merit system requiring a college-level education in a normal school (teacher's college).

The rapid growth in size and complexity the large urban school systems

facilitated stable employment for women teachers and provided senior

teachers greater opportunities to mentor younger teachers. By 1900 in Providence, Rhode Island,

most women remained as teachers for at least 17.5 years, indicating

teaching had become a significant and desirable career path for women.

Regulation of large corporations and monopolies

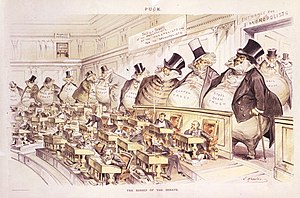

"The Bosses of the Senate", a cartoon by Joseph Keppler

depicting corporate interests–from steel, copper, oil, iron, sugar,

tin, and coal to paper bags, envelopes, and salt–as giant money bags

looming over the tiny senators at their desks in the Chamber of the United States Senate.

Many progressives hoped that by regulating large corporations they could liberate human energies from the restrictions imposed by industrial capitalism. Yet the progressive movement was split over which of the following solutions should be used to regulate corporations.

Trust busting

Pro-labor progressives such as Samuel Gompers

argued that industrial monopolies were unnatural economic institutions

which suppressed the competition which was necessary for progress and

improvement. United States antitrust law is the body of laws that prohibits anti-competitive behavior (monopoly) and unfair business practices. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft supported trust-busting.

During their presidencies, the otherwise-conservative Taft brought down

90 trusts in four years while Roosevelt took down 44 in 7 1/2 years in

office.

Regulation

Progressives such as Benjamin Parke De Witt argued that in a modern economy, large corporations and even monopolies were both inevitable and desirable.

With their massive resources and economies of scale, large corporations

offered the U.S. advantages which smaller companies could not offer.

Yet, these large corporations might abuse their great power. The federal

government should allow these companies to exist but regulate them for

the public interest. President Theodore Roosevelt generally supported

this idea and was later to incorporate it as part of his "New Nationalism".

Social work

Progressives

set up training programs to ensure that welfare and charity work would

be undertaken by trained professionals rather than warm-hearted

amateurs.

Jane Addams of Chicago's Hull House typified the leadership of residential, community centers operated by social workers and volunteers and located in inner city slums. The purpose of the settlement houses was to raise the standard of living of urbanites by providing adult education and cultural enrichment programs.

Anti-prostitution

During

this era of massive reformation among all social aspects, elimination

of prostitution was vital for the progressives, especially the women.

Enactment of child labor laws

A poster highlighting the situation of child labor in the US in the early 20th century

Child labor laws were designed to prevent the overuse of children in

the newly emerging industries. The goal of these laws was to give working class

children the opportunity to go to school and mature more

institutionally, thereby liberating the potential of humanity and

encouraging the advancement of humanity. Factory owners generally did

not want this progression because of lost workers. They used Charles Dickens as a symbol that the working conditions spark imagination. This initiative failed, with child labor laws being enacted anyway.

Support for the goals of organized labor

Labor

unions grew steadily until 1916, then expanded fast during the war. In

1919 a wave of major strikes alienated the middle class; the strikes

were lost, which alienated the workers. In the 1920s the unions were in

the doldrums; in 1924 they supported La Follette's Progressive party,

but he only carried his base in Wisconsin. The American Federation of Labor under Samuel Gompers after 1907 began supporting the Democrats, who promised more favorable judges. The Republicans appointed pro-business judges. Theodore Roosevelt and his third party also supported such goals as the eight-hour work day, improved safety and health conditions in factories, workers' compensation laws, and minimum wage laws for women.

Prohibition

Most progressives, especially in rural areas, adopted the cause of prohibition.

They saw the saloon as political corruption incarnate, and bewailed the

damage done to women and children. They believed the consumption of alcohol limited mankind's potential for advancement. Progressives achieved success first with state laws then with the enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

in 1919. The golden day did not dawn; enforcement was lax, especially

in the cities where the law had very limited popular support and where

notorious criminal gangs, such as the Chicago gang of Al Capone

made a crime spree based on illegal sales of liquor in speakeasies. The

"experiment" (as President Hoover called it) also cost the treasury

large sums of taxes and the 18th amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1933.

Eugenics

Some progressives sponsored eugenics as a solution to excessively large or under-performing families, hoping that birth control would enable parents to focus their resources on fewer, better children. Progressive leaders like Herbert Croly and Walter Lippmann indicated their classically liberal concern over the danger posed to the individual by the practice of eugenics.

Conservation

During the term of the progressive President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) and influenced by the ideas of philosopher-scientists such as George Perkins Marsh, John Wesley Powell, John Muir, Lester Frank Ward and W. J. McGee, the largest government-funded conservation-related projects in U.S. history were undertaken.

National parks and wildlife refuges

On March 14, 1903, President Roosevelt created the first National

Bird Preserve, (the beginning of the Wildlife Refuge system), on Pelican

Island, Florida. In all, by 1909, the Roosevelt administration had created an unprecedented 42 million acres (170,000 km²) of United States National Forests, 53 National Wildlife Refuges and 18 areas of "special interest", such as the Grand Canyon.

Reclamation

In addition, Roosevelt approved the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902, which gave subsidies for irrigation in 13 (eventually 20) western states. Another conservation-oriented bill was the Antiquities Act of 1906 that protected large areas of land by allowing the President to declare areas meriting protection to be national monuments. The Inland Waterways Commission

was appointed by Roosevelt on March 14, 1907 to study the river systems

of the United States, including the development of water power, flood

control, and land reclamation.

National politics

In the early 20th century, politicians of the Democratic and Republican parties, Lincoln–Roosevelt League Republicans (in California) and Theodore Roosevelt's 1912 Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party

all pursued environmental, political, and economic reforms. Chief among

these aims was the pursuit of trust busting, the breaking up very large

monopolies, and support for labor unions, public health programs,

decreased corruption in politics, and environmental conservation.

The progressive movement enlisted support from both major parties (and from minor parties as well). One leader, Democrat William Jennings Bryan, had won both the Democratic Party and the Populist Party

nominations in 1896. At the time, the great majority of other major

leaders had been opposed to Populism. When Roosevelt left the Republican

Party in 1912, he took with him many of the intellectual leaders of

progressivism, but very few political leaders.

The Republican Party then became notably more committed to

business-oriented and efficiency-oriented progressivism, typified by

Taft and Herbert Hoover.

Culture

The foundation of the progressive tendency was indirectly linked to the unique philosophy of pragmatism, which was primarily developed by John Dewey and William James.

Equally significant to progressive-era reform were the crusading journalists, known as muckrakers.

These journalists publicized, to middle class readers, economic

privilege, political corruption, and social injustice. Their articles

appeared in McClure's Magazine and other reform periodicals. Some muckrakers focused on corporate abuses. Ida Tarbell, for instance, exposed the activities of the Standard Oil Company. In The Shame of the Cities (1904), Lincoln Steffens dissected corruption in city government. In Following the Color Line (1908), Ray Stannard Baker criticized race relations. Other muckrakers assailed the Senate, railroad companies, insurance companies, and fraud in patent medicine.

Upton Sinclair's The Jungle exposed Americans to the horrors of the Chicago meatpacking plants

Novelists, too, criticized corporate injustices. Theodore Dreiser drew harsh portraits of a type of ruthless businessman in The Financier (1912) and The Titan (1914). In The Jungle (1906), Socialist Upton Sinclair

repelled readers with descriptions of Chicago's meatpacking plants, and

his work led to support for remedial food safety legislation.

Leading intellectuals also shaped the progressive mentality. In Dynamic Sociology (1883) Lester Frank Ward laid out the philosophical foundations of the Progressive movement and attacked the laissez-faire policies advocated by Herbert Spencer and William Graham Sumner. In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen attacked the "conspicuous consumption" of the wealthy. Educator John Dewey emphasized a child-centered philosophy of pedagogy, known as progressive education, which affected schoolrooms for three generations.

In the 21st century

Progressivism

in the 21st century is significantly different from the historical

progressivism of the 19th-20th centuries. According to Princeton

economics professor Thomas C. Leonard,

"At a glance, there is not much here for 21st-century progressives to

claim kinship with. Today’s progressives emphasize racial equality and

minority rights, decry U.S. imperialism, shun biological ideas in social

science, and have little use for piety or proselytizing." However,

both historical progressivism and the modern movement shares the notion

that the free markets lead to economic inequalities that must be

ameliorated. Many modern progressives have used the term "new progressivism" to make this distinction.

Mitigating income inequality

Income inequality in the United States has been on the rise since 1970, as the wealthy continue to hold more and more wealth and income. For example, 95% of income gains from 2009 to 2013 went to the top 1% of wage earners in the United States. Progressives have recognized that lower union rates, weak policy, globalization, and other drivers have caused the gap in income. The rise of income inequality has led Progressives to draft legislation including, but not limited to, reforming Wall Street, reforming the tax code, reforming campaign finance, closing loopholes, and keeping domestic work.

Wall Street reform

Progressives

began to demand stronger Wall Street regulation after they perceived

deregulation and relaxed enforcement as leading to the financial crisis

of 2008. Passing the Dodd-Frank

financial regulatory act in 2010 provided increased oversight on

financial institutions and the creation of new regulatory agencies, but

many Progressives argue its broad framework allows for financial

institutions to continue to take advantage of consumers and the

government. Bernie Sanders, among others, has advocated to reimplement Glass-Steagall

for its stricter regulation and to break up the banks because of

financial institutions' market share being concentrated in fewer

corporations than progressives would like.

Health care reform

Senator Bernie Sanders has been an advocate of single-payer healthcare.

In 2009, the Congressional Progressive Caucus

outlined five key healthcare principles they intended to pass into law.

The CPC mandated a nationwide public option, affordable health

insurance, insurance market regulations, an employer insurance provision

mandate, and comprehensive services for children. In March 2010, Congress passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which was intended to increase the affordability and efficiency of the United States healthcare

system. Although considered a success by progressives, many argued that

it didn't go far enough in achieving healthcare reform, as exemplified

with the Democrats' failure in achieving a national public option. In recent decades, Single-payer healthcare has become an important goal in healthcare reform for progressives. In the 2016 Democratic Primary, progressive and democratic socialist

presidential candidate Bernie Sanders raised the issue of a

single-payer healthcare system, citing his belief that millions of

Americans are still paying too much for health insurance, and arguing

that millions more don't receive the care they need. In 2016, an effort was made to implement a single-payer healthcare system in the state of Colorado, known as ColoradoCare (Amendment 69). Senator Bernie Sanders held rallies in Colorado in support of the Amendment leading up to the vote.

Despite high-profile support, Amendment 69 failed to pass, with just

21.23% of voting Colorado residents voting in favor, and 78.77% against.

Minimum wage

Adjusted for inflation, the minimum wage peaked in 1968 at around $9.90 (in 2020 dollars).

Progressives believe that stagnating wages perpetuate income inequality

and that raising the minimum wage is a necessary step to combat

inequality.

If the minimum wage grew at the rate of productivity growth in the

United States, it would be $21.72 an hour, nearly three times as much as

the current $7.25 an hour. Popular progressives, such as Senator Bernie Sanders and former Minnesota congressman Keith Ellison, have endorsed a federally mandated wage increase to $15 an hour.

The movement has already seen success with its implementation in

California with the passing of bill to raise the minimum wage $1 every

year until reaching $15 an hour in 2021. New York workers are lobbying for similar legislation as many continue to rally for a minimum wage increase as part of the Fight for $15 movement.

Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter is an international activist group that fights against police brutality and systemic racism.

Black Lives Matter has organized protests against the deaths of

African-Americans by police actions and crimes. These include protests

against the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Korryn Gaines.

Environmental justice

Modern

progressives advocate for strong environmental protections and measures

to reduce or eliminate pollution. One reason for this is the strong

link between economic injustice and adverse environmental conditions:

groups that are economically marginalized tend to be disproportionately

affected by the harms of pollution and environmental degradation.

Definition

With the rise in popularity of self-proclaimed progressives such as Bernie Sanders, Andrew Yang, and Elizabeth Warren, the term began to carry greater cultural currency, particularly in the 2016 Democratic primaries. While answering a question from CNN moderator Anderson Cooper regarding her willingness to shift positions during an October 2015 debate, Hillary Clinton

referred to herself as a "progressive who likes to get things done",

drawing the ire of a number of Sanders supporters and other critics from

her left. Questions about the precise meaning of the term have persisted within the Democratic Party and without since the election of Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election,

with some candidates using it to indicate their affiliation with the

left flank of the party. As such, "progressive" and "progressivism" are essentially contested concepts,

with different groups and individuals defining the terms in different

(and sometimes contradictory) ways towards different (and sometimes

contradictory) ends.

Other progressive parties

Following

the first progressive movement of the early 20th century, two later

short-lived parties have also identified as "progressive".

Progressive Party, 1924

In 1924, Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette

ran for president on the "Progressive party" ticket. La Follette won

the support of labor unions, Germans and Socialists by his crusade. He

carried only Wisconsin and the party vanished outside Wisconsin.

There, it remained a force until the 1940s.

Progressive Party, 1948

A third party was initiated in 1948 by former Vice President Henry A. Wallace

as a vehicle for his campaign for president. He saw the two parties as

reactionary and war-mongering, and attracted support from left-wing

voters who opposed the Cold War

policies that had become a national consensus. Most liberals, New

Dealers, and especially the CIO unions, denounced the party because it

was increasingly controlled by Communists. It faded away after winning

2% of the vote in 1948.