| 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius | |

|---|---|

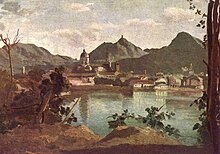

The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (c. 1821) by John Martin

| |

| Volcano | Mount Vesuvius |

| Date | August 24–25 (Traditional) or c. October/November (modern hypothesis), 79 AD |

| Type | Plinian, Peléan |

| Location | Campania, Italy 40°49′N 14°26′ECoordinates: 40°49′N 14°26′E |

| VEI | 5 |

| Impact | Buried the Roman settlements of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae. |

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius in Italy, the most famous is the eruption in 79 AD. This eruption is one of the deadliest in European history.

Mount Vesuvius violently spewed forth a deadly cloud of super-heated tephra and gases to a height of 33 km (21 mi), ejecting molten rock, pulverized pumice and hot ash at 1.5 million tons per second, ultimately releasing 100,000 times the thermal energy of the Hiroshima-Nagasaki bombings. The event gives its name to the Vesuvian type of volcanic eruptions, characterised by eruption columns of hot gases and ash exploding into the stratosphere, although the event also included pyroclastic flows associated with Pelean eruptions.

Several Roman cities were obliterated and buried underneath massive pyroclastic surges and ashfall deposits, the best known being Pompeii and Herculaneum. After archaeological excavations revealed much about the lives of the inhabitants, the area became a major tourist attraction, and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and part of Vesuvius National Park.

The total population of both cities was over 20,000. The remains of over 1,500 people have so far been found at Pompeii and Herculaneum, although the total death toll remains unknown.

Precursors and foreshocks

The Last Day of Pompeii. Painting by Karl Brullov, 1830–1833

The inhabitants had been accustomed to minor earth tremors in the region; the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania".

The first major earthquake since 217 BC occurred on February 5, 62 AD causing widespread destruction around the Bay of Naples, and particularly to Pompeii. Some of the damage had still not been repaired when the volcano erupted.

Another smaller earthquake took place in 64 AD; it was recorded by Suetonius in his biography of Nero, and by Tacitus in Annales because it took place while Nero was in Naples performing for the first time in a public theatre.

Suetonius recorded that the emperor continued singing through the

earthquake until he had finished his song, while Tacitus wrote that the

theatre collapsed shortly after being evacuated.

Small earthquakes were felt for four days before the eruption, becoming more frequent, but the warnings were not recognised.

Nature of the eruption

Reconstructions

of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but

have the same overall features. The eruption lasted for two days. The

morning of the first day was perceived as normal by the only eyewitness

to leave a surviving document, Pliny the Younger, who at that point was staying at Misenum,

on the other side of the Bay of Naples about 29 kilometres (18 mi) from

the volcano, which may have prevented him from noticing the early signs

of the eruption. He was not to have any opportunity, during the next

two days, to talk to people who had witnessed the eruption from Pompeii

or Herculaneum (indeed he never mentions Pompeii in his letter), so he

would not have noticed early, smaller fissures and releases of ash and

smoke on the mountain, if such had occurred earlier in the morning.

Around 1:00 p.m., Mount Vesuvius violently erupted, spewing up a

high-altitude column from which ash and pumice began to fall, blanketing

the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this time. At some time

in the night or early the next day, pyroclastic flows

in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights seen on the mountain

were interpreted as fires. People as far away as Misenum fled for their

lives. The flows were rapid-moving, dense, and very hot, knocking down

wholly or partly all structures in their path, incinerating or

suffocating the remaining population and altering the landscape,

including the coastline. These were accompanied by additional light

tremors and a mild tsunami

in the Bay of Naples. By evening of the second day, the eruption was

over, leaving only haze in the atmosphere through which the sun shone

weakly.

Pliny the Younger wrote an account of the eruption:

Broad sheets of flame were lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the more vivid for the darkness of the night... it was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was darker and thicker than any night.

Stratigraphic studies

Pompeii

and Herculaneum, as well as other cities affected by the eruption of

Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of

ash, pumice and cinders. Modern coast lines are shown; Pliny the Younger was at Misenum.

Sigurðsson, Cashdollar, and Sparks

undertook a detailed stratigraphic study of the layers of ash, based on

excavations and surveys, which was published in 1982. Their conclusion

was that the eruption of Vesuvius of 79 AD unfolded in two phases, Vesuvian and Pelean, which alternated six times.

First, the Plinian eruption, which consisted of a column of volcanic debris and hot gases ejected between 15 km (9 mi) and 30 km (19 mi) high into the stratosphere,

lasted eighteen to twenty hours and produced a fall of pumice and ashes

southward of the volcano that accumulated up to depths of 2.8 m (9 ft)

at Pompeii.

Then, in the Pelean eruption phase, pyroclastic surges of molten rock and hot gases flowed over the ground, reaching as far as Misenum,

which were concentrated to the west and northwest. Two pyroclastic

surges engulfed Pompeii with a 1.8 m (6 ft) deep layer, burning and

asphyxiating any living beings who had remained behind. Herculaneum and Oplontis

received the brunt of the surges and were buried in fine pyroclastic

deposits, pulverized pumice and lava fragments up to 20 m (70 ft) deep.

Surges 4 and 5 are believed by the authors to have destroyed and buried

Pompeii. Surges are identified in the deposits by dune and cross-bedding formations, which are not produced by fallout.

The eruption is viewed as primarily phreatomagmatic,

where the chief energy supporting the blast column came from escaping

steam created from seawater seeping over time into the deep-seated

faults of the region, coming into contact with hot magma.

Timing of explosions

In

an article published in 2002, Sigurðsson and Casey concluded that an

early explosion produced a column of ash and pumice which rained on

Pompeii to the southeast but not on Herculaneum, which was upwind. Subsequently, the cloud collapsed as the gases densified and lost their capability to support their solid contents.

The authors suggest that the first ash falls are to be

interpreted as early-morning, low-volume explosions not seen from

Misenum, causing Rectina

to send her messenger on a ride of several hours around the Bay of

Naples, then passable, providing an answer to the paradox of how the

messenger might miraculously appear at Pliny's villa so shortly after a

distant eruption that would have prevented him.

Magnetic studies

Inside the crater of Vesuvius

A 2006 study by Zanella, Gurioli, Pareschi, and Lanza used the

magnetic characteristics of over 200 samples of lithic, roof-tile, and

plaster fragments collected from pyroclastic deposits in and around

Pompeii to estimate the equilibrium temperatures of the deposits. The deposits were placed by pyroclastic density currents

(PDCs) resulting from the collapses of the Plinian column. The authors

argue that fragments over 2–5 cm (0.8–2 in) were not in the current long

enough to acquire its temperature, which would have been much higher,

and therefore they distinguish between the depositional temperatures,

which they estimated, and the emplacement temperatures, which in some

cases based on the cooling characteristics of some types and fragment

sizes of rocks they believed they also could estimate. Final figures are

considered to be those of the rocks in the current just before

deposition.

All crystal rock contains some iron or iron compounds, rendering it ferromagnetic,

as do Roman roof tiles and plaster. These materials may acquire a

residual field from a number of sources. When individual molecules,

which are magnetic dipoles, are held in alignment by being bound in a crystalline structure, the small fields reinforce each other to form the rock's residual field. Heating the material adds internal energy to it. At the Curie temperature,

the vibration of the molecules is sufficient to disrupt the alignment;

the material loses its residual magnetism and assumes whatever magnetic field

might be applied to it only for the duration of the application. The

authors term this phenomenon unblocking. Residual magnetism is

considered to "block out" non-residual fields.

A rock is a mixture of minerals, each with its own Curie temperature; the authors therefore looked for a spectrum

of temperatures rather than a single temperature. In the ideal sample,

the PDC did not raise the temperature of the fragment beyond the highest

blocking temperature. Some constituent material retained the magnetism

imposed by the Earth's field when the item was formed. The temperature

was raised above the lowest blocking temperature and therefore some

minerals on recooling acquired the magnetism of the Earth as it was in

79 AD. The overall field of the sample was the vector sum of the fields of the high-blocking material and the low-blocking material.

This type of sample made possible estimation of the low

unblocking temperature. Using special equipment that measured field

direction and strength at various temperatures, the experimenters raised

the temperature of the sample in increments of 40 °C (70 °F) from 100 °C (210 °F) until it reached the low unblocking temperature.

Deprived of one of its components, the overall field changed direction.

A plot of direction at each increment identified the increment at which

the sample's resultant magnetism had formed.

That was considered to be the equilibrium temperature of the deposit.

Considering the data for all the deposits of the surge arrived at a

surge deposit estimate. The authors discovered that the city, Pompeii,

was a relatively cool spot within a much hotter field, which they

attributed to interaction of the surge with the "fabric" of the city.

The investigators reconstruct the sequence of volcanic events as follows:

- On the first day of the eruption a fall of white pumice containing clastic fragments of up to 3 centimetres (1 in) fell for several hours. It heated the roof tiles to 120–140 °C (250–280 °F). This period would have been the last opportunity to escape. Subsequently, a second column deposited a grey pumice with clastics up to 10 cm (4 in), temperature unsampled, but presumed to be higher, for 18 hours. These two falls were the Plinian phase. The collapse of the edges of these clouds generated the first dilute PDCs, which must have been devastating to Herculaneum, but did not enter Pompeii.

- Early in the morning of the second day the grey cloud began to collapse to a greater degree. Two major surges struck and destroyed Pompeii. Herculaneum and all its population no longer existed. The emplacement temperature range of the first surge was 180–220 °C (360–430 °F), minimum temperatures; of the second, 220–260 °C (430–500 °F). The depositional temperature of the first was 140–300 °C (280–570 °F). Upstream and downstream of the flow it was 300–360 °C (570–680 °F).

The variable temperature of the first surge was due to interaction

with the buildings. Any population remaining in structural refuges could

not have escaped, as the city was surrounded by gases of incinerating

temperatures. The lowest temperatures were in rooms under collapsed

roofs. These were as low as 100 °C (212 °F), the boiling point of water.

The authors suggest that elements of the bottom of the flow were

decoupled from the main flow by topographic irregularities and were made

cooler by the introduction of ambient turbulent air. In the second

surge the irregularities were gone and the city was as hot as the

surrounding environment.

During the last surge, which was very dilute, one metre more of deposits fell over the region.

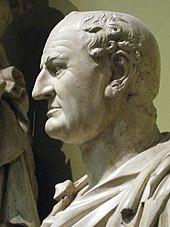

The Two Plinys

Pompeii, with Vesuvius towering above

The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger, who was 17 at the time of the eruption, to the historian Tacitus and written some 25 years after the event. Observing the first volcanic activity from Misenum

across the Bay of Naples from the volcano, approximately 29 kilometres

(18 mi) away, the elder Pliny launched a rescue fleet and went himself

to the rescue of a personal friend. His nephew declined to join the

party. One of the nephew's letters relates what he could discover from

witnesses of his uncle's experiences. In a second letter, the younger Pliny details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

Pliny the Younger

Pliny the Younger saw an extraordinarily dense cloud rising rapidly above the mountain:

the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to that of a pine-tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches. [...] it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.

These events and a request by messenger for an evacuation by sea

prompted the elder Pliny to order rescue operations in which he sailed

away to participate. His nephew attempted to resume a normal life,

continuing to study, and bathing, but that night a tremor woke him and

his mother, prompting them to abandon the house for the courtyard. At

another tremor near dawn the population abandoned the village. After

still a third "the sea seemed to roll back upon itself, and to be driven

from its banks", which is evidence for a tsunami. There is, however, no evidence of extensive damage from wave action.

The early light was obscured by a black cloud through which shone

flashes, which Pliny likens to sheet lightning, but more extensive. The

cloud obscured Point Misenum near at hand and the island of Capraia (Capri)

across the bay. Fearing for their lives the population began to call to

each other and move back from the coast along the road. Pliny's mother

requested him to abandon her and save his own life, as she was too

corpulent and aged to go further, but seizing her hand he led her away

as best he could. A rain of ash fell. Pliny found it necessary to shake

off the ash periodically to avoid being buried. Later that same day the

ash stopped falling and the sun shone weakly through the cloud,

encouraging Pliny and his mother to return to their home and wait for

news of Pliny the Elder. The letter compares the ash to a blanket of

snow. Evidently the earthquake and tsunami damage at that location were

not severe enough to prevent continued use of the home.

Pliny the Elder

Pliny's uncle Pliny the Elder was in command of the Roman fleet

at Misenum, and had meanwhile decided to investigate the phenomenon at

close hand in a light vessel. As the ship was preparing to leave the

area, a messenger came from his friend Rectina (wife of Bassus) living on the coast near the foot of the volcano, explaining that her party could only get away by sea and asking for rescue.

Pliny ordered the immediate launching of the fleet galleys to the

evacuation of the coast. He continued in his light ship to the rescue of

Rectina's party.

He set off across the bay but in the shallows on the other side

encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice, and pieces of

rock. Advised by the helmsman to turn back he stated "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to continue on to Stabiae (about 4.5 km or 2.8 mi from Pompeii), where Pomponianus was.

Pomponianus had already loaded a ship with possessions and was

preparing to leave, but the same onshore wind that brought Pliny's ship

to the location had prevented anyone from leaving.

Pliny and his party saw flames coming from several parts of the

mountain, which Pliny and his friends attributed to burning villages.

After staying overnight, the party was driven from the building by an

accumulation of material which threatened to block all egress.

They woke Pliny, who had been napping and snoring loudly. They elected

to take to the fields with pillows tied to their heads to protect them

from rockfall. They approached the beach again, but the wind had not

changed. Pliny sat down on a sail that had been spread for him and could

not rise, even with assistance. His friends then departed, escaping

ultimately by land.

Very likely, he had collapsed and died, the most popular explanation

for why his friends abandoned him, although Suetonius offers an

alternative story of his ordering a slave to kill him to avoid the pain

of incineration. How the slave would have escaped to tell the tale

remains a mystery. There is no mention of such an event in his nephew's

letters.

In the first letter to Tacitus his nephew suggested that his

death was due to the reaction of his weak lungs to a cloud of poisonous,

sulphurous gas that wafted over the group. However, Stabiae was 16 km (9.9 mi) from the vent (roughly where the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia

is situated) and his companions were apparently unaffected by the

fumes, and so it is more likely that the corpulent Pliny died from some

other cause, such as a stroke or heart attack. An asthmatic

attack is also not out of the question. His body was found with no

apparent injuries on the next day, after dispersal of the plume.

Casualties from the eruption

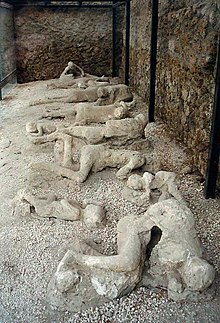

The casts of some victims in the so-called "Garden of the Fugitives", Pompeii.

Along with Pliny the Elder, the only other notable casualties of the eruption to be known by name were the Jewish princess Drusilla and her son Agrippa, who was born in her marriage with the procurator Antonius Felix. It is also said that the poet Caesius Bassus died in the eruption.

By 2003, approximately 1,044 casts made from impressions of

bodies in the ash deposits had been recovered in and around Pompeii,

with the scattered bones of another 100. The remains of about 332 bodies have been found at Herculaneum (300 in arched vaults discovered in 1980). The total number of fatalities remains unknown.

The skeleton called the "Ring Lady" unearthed in Herculaneum

Thirty-eight percent of the 1,044 were found in the ash fall deposits, the majority inside buildings.

This differs from modern experience over the last 400 years when only

around 4% of victims have been killed by ash falls during explosive

eruptions. This cohort was possibly sheltering in buildings when they

were overcome. The remaining 62% of bodies found at Pompeii lay in the pyroclastic surge

deposits which probably killed them. It was initially believed that due

to the state of the bodies found at Pompeii and the outline of clothes

on the bodies it was unlikely that high temperatures were a significant

cause. Later studies indicated that during the fourth pyroclastic surge

(the first surge to reach Pompeii) temperatures reached 300 °C (572 °F)

which was enough to kill people in a fraction of a second.

The contorted postures of bodies as if frozen in suspended action were

not the effects of long agony, but of the cadaveric spasm, a consequence

of heat shock on corpses. The heat was so intense that organs and blood were vaporised, and at least one victim's brain was vitrified by the temperature.

Herculaneum, which was much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra

falls by the wind direction but was buried under 23 metres (75 ft) of

material deposited by pyroclastic surges. It is likely that most, or

all, of the known victims in this town were killed by the surges,

particularly given evidence of high temperatures found on the skeletons

of the victims found in the arched vaults on the seashore and the

existence of carbonised wood in many of the buildings. These people were

concentrated in the vaults at a density as high as three per square

metre and were all caught by the first surge, dying of thermal shock and

partly carbonised by later and hotter surges. The vaults were most

likely boathouses, as the crossbeams overhead were probably for the

suspension of boats used for the earlier escape of some of the

population. As only 85 metres (279 ft) of the coast have been excavated,

more casualties may be waiting to be excavated.

Date of the eruption

In

October 2018, Italian archaeologists uncovered a charcoal inscription

dated October 17 (of 79 AD as it was unlikely to have been a year old) which sets the earliest possible date for the eruption.

Support for an October/November eruption has long been known in several

respects: bodies buried in the ash were wearing heavier clothing than

the light summer clothes typical of August; fresh fruit and vegetables

in the shops are typical of October, and the summer fruit typical of

August was already being sold in dried or conserved form; wine

fermenting jars had been sealed, which would have happened around the

end of October; coins found in the purse of a woman buried in the ash

include one with a 15th imperatorial acclamation among the emperor's

titles and could not have been minted before the second week of

September.

Vesuvius and its destructive eruption are mentioned in

first-century Roman sources, but not the day of the eruption. For

example, Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews mentions that the eruption occurred "in the days of Titus Caesar."

Suetonius, a second-century historian, in his Life of Titus simply says that, "There were some dreadful disasters during his reign, such as the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Campania."

Writing well over a century after the actual event, Roman historian Cassius Dio (as translated in the Loeb Classical Library

1925 edition) wrote that, "In Campania remarkable and frightful

occurrences took place; for a great fire suddenly flared up at the very

end of the summer."

For the past five centuries, articles about the eruption of Vesuvius have typically said that the eruption began on August 24 of 79 AD. This date came from a 1508 printed version of a letter between Pliny the Younger and the Roman historian Tacitus, written some 25 years after the event.

Pliny was a witness to the eruption and provides the only known

eyewitness account. Over fourteen centuries of manuscript hand-copying

up to the 1508 printing of his letters, the date given in Pliny's

original letter may have been corrupted. Manuscript experts believe that

the date originally given by Pliny was one of August 24, October 30,

November 1, or November 23. This odd scattered set of dates is due to the Romans' convention for describing calendar dates.

The large majority of extant medieval manuscript copies – there are no

surviving Roman copies – indicate a date corresponding to August 24, and

from the discovery of the cities into the 21st century this was

accepted by most scholars and by nearly all books written about Pompeii

and Herculaneum for the general public.

Since at least the late 18th century, a minority among archaeologists and other scientists have suggested that the eruption began after August 24, during the autumn, perhaps in October or November. In 1797 the researcher Carlo Rosini reported that excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum had uncovered traces of fruits and braziers indicative of the autumn, not the summer.

More recently, in 1990 and 2001, archaeologists discovered more

remnants of autumnal fruits (such as the pomegranate), the remains of

victims of the eruption in heavy clothing, and large earthenware storage

vessels laden with wine (at the time of their burial by Vesuvius). The

wine-related discovery may show that the eruption was after the year's

grape harvest and wine making.

In 2007 a study of prevailing winds in Campania showed that the

southeasterly debris pattern of the first-century eruption is quite

consistent with an autumn event, and inconsistent with an August date.

During June, July, and August, the prevailing winds flow to the west –

an arc between the southwest and northwest – virtually all the time. (Note that the Julian calendar was in place throughout the first century AD – that is, the months of the Roman calendar were aligned with the seasons.)

As Emperor Titus of the Flavian dynasty (reigning June 24, 79 to September 13, 81) garnered victories on the battlefield (including his capture of the Temple of Jerusalem),

and other honors, his administration issued coins enumerating his

ever-growing accolades. Given the limited space on each coin, his

achievements were stamped on the coins using an arcane encoding. Two of

these coins, from early in Titus' reign, were found in a hoard recovered

at Pompeii's House of the Golden Bracelet. Although the coins' minting

dates are somewhat in dispute, a numismatic expert at the British Museum,

Richard Abdy, concluded that the latest coin in the hoard was minted on

or after June 24 (the first date of Titus' reign) and before September 1

of 79 AD. Abdy states that it is "remarkable that both coins will have

taken just two months after minting to enter circulation and reach

Pompeii before the disaster."