Possible scenario of clean mobility

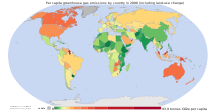

Anthropogenic per capita emissions of greenhouse gases by country by the year 2000

Sustainable transport refers to the broad subject of transport that is sustainable in the senses of social, environmental and climate impacts. Components for evaluating sustainability include the particular vehicles used for road, water or air transport; the source of energy; and the infrastructure used to accommodate the transport (roads, railways, airways, waterways, canals and terminals). Transport operations and logistics as well as transit-oriented development

are also involved in evaluation. Transportation sustainability is

largely being measured by transportation system effectiveness and

efficiency as well as the environmental and climate impacts of the system.

Short-term activity often promotes incremental improvement in fuel efficiency and vehicle emissions controls while long-term goals include migrating transportation from fossil-based energy to other alternatives such as renewable energy and use of other renewable resources. The entire life cycle of transport systems is subject to sustainability measurement and optimization.

Sustainable transport systems make a positive contribution to the environmental, social and economic sustainability

of the communities they serve. Transport systems exist to provide

social and economic connections, and people quickly take up the

opportunities offered by increased mobility, with poor households benefiting greatly from low carbon transport options.

The advantages of increased mobility need to be weighed against the

environmental, social and economic costs that transport systems pose.

Transport systems have significant impacts on the environment, accounting for between 20% and 25% of world energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. The majority of the emissions, almost 97%, came from direct burning of fossil fuels. Greenhouse gas emissions from transport are increasing at a faster rate than any other energy using sector. Road transport is also a major contributor to local air pollution and smog.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that each year 2.4 million premature deaths from outdoor air pollution could be avoided. Particularly hazardous for health are emissions of black carbon, a component of particulate matter, which is a known cause of respiratory and carcinogenic diseases and a significant contributor to global climate change. The links between greenhouse gas emissions and particulate matter make low carbon

transport an increasingly sustainable investment at local level—both by

reducing emission levels and thus mitigating climate change; and by

improving public health through better air quality.

The social costs of transport include road crashes, air pollution, physical inactivity, time taken away from the family while commuting and vulnerability to fuel price increases. Many of these negative impacts fall disproportionately on those social groups who are also least likely to own and drive cars. Traffic congestion imposes economic costs by wasting people's time and by slowing the delivery of goods and services.

Traditional transport planning

aims to improve mobility, especially for vehicles, and may fail to

adequately consider wider impacts. But the real purpose of transport is

access – to work, education, goods and services, friends and family –

and there are proven techniques to improve access while simultaneously

reducing environmental and social impacts, and managing traffic

congestion.

Communities which are successfully improving the sustainability of

their transport networks are doing so as part of a wider programme of

creating more vibrant, livable, sustainable cities.

Definition

The term sustainable transport came into use as a logical follow-on from sustainable development, and is used to describe modes of transport, and systems of transport planning, which are consistent with wider concerns of sustainability. There are many definitions of the sustainable transport, and of the related terms sustainable transportation and sustainable mobility. One such definition, from the European Union Council of Ministers of Transport, defines a sustainable transportation system as one that:

- Allows the basic access and development needs of individuals, companies and society to be met safely and in a manner consistent with human and ecosystem health, and promotes equity within and between successive generations.

- Is affordable, operates fairly and efficiently, offers a choice of transport mode, and supports a competitive economy, as well as balanced regional development.

- Limits emissions and waste within the planet's ability to absorb them, uses renewable resources at or below their rates of generation, and uses non-renewable resources at or below the rates of development of renewable substitutes, while minimizing the impact on the use of land and the generation of noise.

Sustainability extends beyond just the operating efficiency and emissions. A life-cycle assessment involves production, use and post-use considerations. A cradle-to-cradle design is more important than a focus on a single factor such as energy efficiency.

History

Most of the tools and concepts of sustainable transport were developed before the phrase was coined. Walking, the first mode of transport, is also the most sustainable. Public transport dates back at least as far as the invention of the public bus by Blaise Pascal in 1662. The first passenger tram began operation in 1807 and the first passenger rail service in 1825. Pedal bicycles date from the 1860s. These were the only personal transport choices available to most people in Western countries prior to World War II, and remain the only options for most people in the developing world. Freight was moved by human power, animal power or rail.

Mass motorisation

Carbon emissions per passenger

Overall GHG from transport

The post-war years brought increased wealth and a demand for much

greater mobility for people and goods. The number of road vehicles in

Britain increased fivefold between 1950 and 1979,

with similar trends in other Western nations. Most affluent countries

and cities invested heavily in bigger and better-designed roads and

motorways, which were considered essential to underpin growth and

prosperity. Transport planning became a branch of Urban Planning and identified induced demand as a pivotal change from "predict and provide" toward a sustainable approach incorporating land use planning and public transit. Public investment in transit, walking and cycling

declined dramatically in the United States, Great Britain and

Australia, although this did not occur to the same extent in Canada or

mainland Europe.

Concerns about the sustainability of this approach became widespread during the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis.

The high cost and limited availability of fuel led to a resurgence of

interest in alternatives to single occupancy vehicle travel.

Transport innovations dating from this period include high-occupancy vehicle lanes, citywide carpool systems and transportation demand management. Singapore implemented congestion pricing in the late 1970s, and Curitiba began implementing its Bus Rapid Transit system in the early 1980s.

Relatively low and stable oil prices during the 1980s and 1990s

led to significant increases in vehicle travel from 1980–2000, both

directly because people chose to travel by car more often and for

greater distances, and indirectly because cities developed tracts of

suburban housing, distant from shops and from workplaces, now referred

to as urban sprawl. Trends in freight logistics, including a movement from rail and coastal shipping to road freight and a requirement for just in time deliveries, meant that freight traffic grew faster than general vehicle traffic.

At the same time, the academic foundations of the "predict and provide" approach to transport were being questioned, notably by Peter Newman in a set of comparative studies of cities and their transport systems dating from the mid-1980s.

The British Government's White Paper on Transport marked a change in direction for transport planning in the UK. In the introduction to the White Paper, Prime Minister Tony Blair stated that

We recognise that we cannot simply build our way out of the problems we face. It would be environmentally irresponsible – and would not work.

A companion document to the White Paper called "Smarter Choices"

researched the potential to scale up the small and scattered sustainable

transport initiatives then occurring across Britain, and concluded that

the comprehensive application of these techniques could reduce peak

period car travel in urban areas by over 20%.

A similar study by the United States Federal Highway Administration,

was also released in 2004 and also concluded that a more proactive

approach to transportation demand was an important component of overall

national transport strategy.

Environmental impact

The Bus Rapid Transit of Metz uses a diesel-electric hybrid driving system, developed by Belgian Van Hool manufacturer.

Electric Transmetro in Guatemala City

Transport systems are major emitters of greenhouse gases, responsible

for 23% of world energy-related GHG emissions in 2004, with about three

quarters coming from road vehicles. Currently 95% of transport energy

comes from petroleum. Energy is consumed in the manufacture as well as the use of vehicles, and is embodied in transport infrastructure including roads, bridges and railways.

The first historical attempts of evaluating the Life Cycle environmental impact of vehicle is due to Theodore Von Karman.

After decades in which all the analysis has been focused on emending

the Von Karman model, Dewulf and Van Langenhove have introduced a model

based on the second law of thermodynamics and exergy analysis. Chester and Orwath, have developed a similar model based on the first law that accounts the necessary costs for the infrastructure.

The environmental impacts of transport can be reduced by reducing the weight of vehicles,

sustainable styles of driving, reducing the friction of tires,

encouraging electric and hybrid vehicles, improving the walking and cycling environment in cities, and by enhancing the role of public transport, especially electric rail.

Green vehicles

are intended to have less environmental impact than equivalent standard

vehicles, although when the environmental impact of a vehicle is

assessed over the whole of its life cycle this may not be the case.

Electric vehicle technology (especially non-battery based vehicles, fuel cell vehicles, ...) has the potential to reduce transport CO2 emissions, depending on the embodied energy of the vehicle and the source of the electricity.

The primary sources of electricity currently used in most countries

(coal, gas, oil) mean that until world electricity production changes

substantially, private electric cars will result in the same or higher

production of CO

2 than petrol equivalent vehicles. Battery-based electric vehicles may or may not be better in terms of GHG emissions then fossil-fuel based vehicles depending on several factors, such as battery type, capacity of the battery, life expectancy of the battery, ...

2 than petrol equivalent vehicles. Battery-based electric vehicles may or may not be better in terms of GHG emissions then fossil-fuel based vehicles depending on several factors, such as battery type, capacity of the battery, life expectancy of the battery, ...

The Online Electric Vehicle (OLEV), developed by the Korea

Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), is an electric

vehicle that can be charged while stationary or driving, thus removing

the need to stop at a charging station. The City of Gumi in South Korea

runs a 24 km roundtrip along which the bus will receive 100 kW (136

horsepower) electricity at an 85% maximum power transmission efficiency

rate while maintaining a 17 cm air gap between the underbody of the

vehicle and the road surface.

At that power, only a few sections of the road need embedded cables. Hybrid vehicles, which use an internal combustion engine combined with an electric engine to achieve better fuel efficiency than a regular combustion engine, are already common.

Natural gas

is also used as a transport fuel but is a less promising, technology as

it is still a fossil fuel and still has significant emissions (though

lower than gasoline, diesel, ...).

Brazil met 17% of its transport fuel needs from bioethanol in 2007, but the OECD

has warned that the success of (first-generation) biofuels in Brazil is

due to specific local circumstances. Internationally, first-generation

biofuels are forecast to have little or no impact on greenhouse

emissions, at significantly higher cost than energy efficiency measures.

The later generation biofuels however (2nd to 4th generation) do have

significant environmental benefit, as they are no driving force for

deforestation or struggle with the food vs fuel issue.

Other renewable fuels include hydrogen, which (like drop-in biofuels) can be used in internal combustion vehicles, don't rely on any crops at all (instead it's produced using electricity) and even generates very little pollution when burned.

In practice there is a sliding scale of green transport depending on the sustainability of the option. Green vehicles are more fuel-efficient,

but only in comparison with standard vehicles, and they still

contribute to traffic congestion and road crashes. Well-patronised public transport

networks based on traditional diesel buses use less fuel per passenger

than private vehicles, and are generally safer and use less road space

than private vehicles. Green public transport vehicles including electric trains, trams and electric buses

combine the advantages of green vehicles with those of sustainable

transport choices. Other transport choices with very low environmental

impact are cycling and other human-powered vehicles, and animal powered transport. The most common green transport choice, with the least environmental impact is walking.

Transport on rails boasts an excellent efficiency.

Transport and social sustainability

Cities with overbuilt roadways have experienced unintended consequences, linked to radical drops in public transport, walking, and cycling.

In many cases, streets became void of “life.” Stores, schools,

government centers and libraries moved away from central cities, and

residents who did not flee to the suburbs experienced a much reduced

quality of public space and of public services. As schools were closed

their mega-school replacements in outlying areas generated additional

traffic; the number of cars on US roads between 7:15 and 8:15 a.m.

increases 30% during the school year.

Yet another impact was an increase in sedentary lifestyles, causing and complicating a national epidemic of obesity, and accompanying dramatically increased health care costs.

Cities

Futurama, an exhibit at the 1939 New York World's Fair, was sponsored by General Motors and showed a vision of the City of Tomorrow.

Cities are shaped by their transport systems. In The City in History, Lewis Mumford

documented how the location and layout of cities was shaped around a

walkable center, often located near a port or waterway, and with suburbs

accessible by animal transport or, later, by rail or tram lines.

In 1939, the New York World's Fair

included a model of an imagined city, built around a car-based

transport system. In this "greater and better world of tomorrow",

residential, commercial and industrial areas were separated, and

skyscrapers loomed over a network of urban motorways. These ideas

captured the popular imagination, and are credited with influencing city

planning from the 1940s to the 1970s.

The popularity of the car in the post-war era led to major changes in the structure and function of cities. There was some opposition to these changes at the time. The writings of Jane Jacobs, in particular The Death and Life of Great American Cities

provide a poignant reminder of what was lost in this transformation,

and a record of community efforts to resist these changes. Lewis Mumford

asked "is the city for cars or for people?" Donald Appleyard documented the consequences for communities of increasing car traffic in "The View from the Road" (1964) and in the UK, Mayer Hillman first published research into the impacts of traffic on child independent mobility in 1971. Despite these notes of caution, trends in car ownership, car use and fuel consumption continued steeply upward throughout the post-war period.

Mainstream transport planning in Europe has, by contrast, never

been based on assumptions that the private car was the best or only

solution for urban mobility. For example, the Dutch

Transport Structure Scheme has since the 1970s required that demand for

additional vehicle capacity only be met "if the contribution to

societal welfare is positive", and since 1990 has included an explicit

target to halve the rate of growth in vehicle traffic. Some cities outside Europe have also consistently linked transport to sustainability and to land-use planning, notably Curitiba, Brazil, Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Canada.

Greenhouse gas emissions from transport vary widely, even for cities of comparable wealth. Source: UITP, Mobility in Cities Database.

There are major differences in transport energy consumption between

cities; an average U.S. urban dweller uses 24 times more energy annually

for private transport

than a Chinese urban resident, and almost four times as much as a

European urban dweller. These differences cannot be explained by wealth

alone but are closely linked to the rates of walking, cycling, and public transport use and to enduring features of the city including urban density and urban design.

A bypass in the Old Town in Szczecin, Poland

The cities and nations that have invested most heavily in car-based

transport systems are now the least environmentally sustainable, as

measured by per capita fossil fuel use. The social and economic sustainability of car-based transportation engineering has also been questioned. Within the United States, residents of sprawling

cities make more frequent and longer car trips, while residents of

traditional urban neighbourhoods make a similar number of trips, but

travel shorter distances and walk, cycle and use transit more often.

It has been calculated that New York residents save $19 billion each

year simply by owning fewer cars and driving less than the average

American. A less car intensive means of urban transport is carsharing, which is becoming popular in North America and Europe, and according to The Economist, carsharing can reduce car ownership at an estimated rate of one rental car replacing 15 owned vehicles.

Car sharing has also begun in the developing world, where traffic and

urban density is often worse than in developed countries. Companies like

Zoom

in India, eHi in China, and Carrot in Mexico, are bringing car-sharing

to developing countries in an effort to reduce car-related pollution,

ameliorate traffic, and expand the number of people who have access to

cars.

The European Commission adopted the Action Plan on urban mobility

on 30 September 2009 for sustainable urban mobility. The European

Commission will conduct a review of the implementation of the Action

Plan in the year 2012, and will assess the need for further action. In

2007, 72% of the European population lived in urban areas, which are key

to growth and employment. Cities need efficient transport systems to

support their economy and the welfare of their inhabitants. Around 85%

of the EU's GDP is generated in cities. Urban areas face today the challenge of making transport sustainable in environmental (CO2, air pollution, noise) and competitiveness (congestion) terms while at the same time addressing social concerns. These range from the need to respond to health problems and demographic trends, fostering economic and social cohesion to taking into account the needs of persons with reduced mobility, families and children.

The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group

(C40) is a group of 94 cities around the world driving urban action

that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks, while

increasing the health and wellbeing of urban citizens. In October 2019,

by signing the C40 Clean Air Cities Declaration, 35 mayors recognised

that breathing clean air is a human right and committed to work together

to form a global coalition for clean air.

Policies and governance

Seven sustainable transportations in one photo (Prague)

Sustainable transport policies have their greatest impact at the city level.

Some of the biggest cities in Western Europe have a relatively sustainable transport. In Paris 53% of trips are made by walking, 3% by bicycle, 34% by public transport, and only 10% by car. In the entire Ile-de-France region, walking is the most popular way of transportation. In Amsterdam, 28% of trips are made by walking, 31% by bicycle, 18% by public transport and only 23% by car. In Copenhagen 62% of people commute to school or work by bicycle.

Outside Western Europe, cities which have consistently included

sustainability as a key consideration in transport and land use planning

include Curitiba, Brazil; Bogota, Colombia; Portland, Oregon; and Vancouver, Canada. The state of Victoria, Australia passed legislation in 2010 – the Transport Integration Act

– to compel its transport agencies to actively consider sustainability

issues including climate change impacts in transport policy, planning

and operations.

Many other cities throughout the world have recognised the need

to link sustainability and transport policies, for example by joining

the Cities for Climate Protection program.

Some cities are trying to become carfree cities, e.g., limit or exclude the usage of cars.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed several cities to adopt a plan to drastically increase biking and walking; these included Milan, London, Brighton, and Dublin. These plans were taken to facilitate social distancing by avoiding public transport and at the same time prevent a rise in traffic congestion and air pollution from increase in car use. A similar plan was adopted by New York City and Paris.

Community and grassroots action

Sustainable

transport is fundamentally a grassroots movement, albeit one which is

now recognised as of citywide, national and international significance.

Whereas it started as a movement driven by environmental

concerns, over these last years there has been increased emphasis on

social equity and fairness issues, and in particular the need to ensure

proper access and services for lower income groups and people with

mobility limitations, including the fast-growing population of older

citizens. Many of the people exposed to the most vehicle noise,

pollution and safety risk have been those who do not own, or cannot

drive cars, and those for whom the cost of car ownership causes a severe

financial burden.

An organization called Greenxc started in 2011 created a national awareness campaign in the United States encouraging people to carpool

by ride-sharing cross country stopping over at various destinations

along the way and documenting their travel through video footage, posts

and photography.

Ride-sharing reduces individual's carbon footprint by allowing several

people to use one car instead of everyone using individual cars.

At the beginning of the 21st century, some companies are trying to increase the use of sailing ships, even for commercial purposes, for example, Fairtrannsport and New Dawn Traders They have created the Sail Cargo Alliance.

Recent trends

Car travel increased steadily throughout the twentieth century, but trends since 2000 have been more complex. Oil price rises from 2003 have been linked to a decline in per capita fuel use for private vehicle travel in the US,

Britain and Australia. In 2008, global oil consumption fell by 0.8%

overall, with significant declines in consumption in North America,

Western Europe, and parts of Asia.

Other factors affecting a decline in driving, at least in America, include the retirement of Baby Boomers who now drive less, preference for other travel modes (such as transit) by younger age cohorts, the Great Recession,

and the rising use of technology (internet, mobile devices) which have

made travel less necessary and possibly less attractive.

Tools and incentives

Several European countries are opening up financial incentives that support more sustainable modes of transport. The European Cyclists' Federation, which focuses on daily cycling for transport, has created a document containing a non-complete overview. In the UK,

employers have for many years been providing employees with financial

incentives. The employee leases or borrows a bike that the employer has

purchased. You can also get other support. The scheme is beneficial for

the employee who saves money and gets an incentive to get exercise

integrated in the daily routine. The employer can expect a tax

deduction, lower sick leave and less pressure on parking spaces for

cars. Since 2010, there has been a scheme in Iceland

(Samgöngugreiðslur) where those who do not drive a car to work, get

paid a lump of money monthly. An employee must sign a statement not to

use a car for work more often than one day a week, or 20% of the days

for a period. Some employers pay fixed amounts based on trust. Other

employers reimburse the expenses for repairs on bicycles, period-tickets

for public transport and the like. Since 2013, amounts up to ISK 8000

per month have been tax-free. Most major workplaces offer this, and a

significant proportion of employees use the scheme. Since 2019 half the

amount is tax-free if the employee signs a contract not to use a car to

work for more than 40% of the days of the contract period.

Greenwashing

The term green transport is often used as a greenwash

marketing technique for products which are not proven to make a

positive contribution to environmental sustainability. Such claims can

be legally challenged. For instance Norway's consumer ombudsman has targeted automakers who claim that their cars are "green", "clean" or "environmentally friendly". Manufacturers risk fines if they fail to drop the words. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

(ACCC) describes "green" claims on products as "very vague, inviting

consumers to give a wide range of meanings to the claim, which risks

misleading them". In 2008 the ACCC forced a car retailer to stop its green marketing of Saab cars, which was found by the Australian Federal Court to be "misleading".