A land value tax or location value tax (LVT), also called a site valuation tax, split rate tax, or site-value rating, is an ad valorem levy on the unimproved value of land. Unlike property taxes, it disregards the value of buildings, personal property and other improvements to real estate. A land value tax is generally favored by economists as (unlike other taxes) it does not cause economic inefficiency, and it tends to reduce inequality.

Land value tax has been referred to as "the perfect tax" and the economic efficiency of a land value tax has been known since the eighteenth century. Many economists since Adam Smith and David Ricardo have advocated this tax, but it is most famously associated with Henry George, who argued that because the supply of land is fixed and its location value is created by communities and public works, the economic rent of land is the most logical source of public revenue.

A land value tax is a progressive tax, in that the tax burden falls on titleholders in proportion to the value of locations, the ownership of which is highly correlated with overall wealth and income. Land value taxation is currently implemented throughout Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Russia, Singapore, and Taiwan; it has also been applied to smaller extents in subregions of Australia, Mexico (Mexicali), and the United States (e.g., Pennsylvania).

Land value tax has been referred to as "the perfect tax" and the economic efficiency of a land value tax has been known since the eighteenth century. Many economists since Adam Smith and David Ricardo have advocated this tax, but it is most famously associated with Henry George, who argued that because the supply of land is fixed and its location value is created by communities and public works, the economic rent of land is the most logical source of public revenue.

A land value tax is a progressive tax, in that the tax burden falls on titleholders in proportion to the value of locations, the ownership of which is highly correlated with overall wealth and income. Land value taxation is currently implemented throughout Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Russia, Singapore, and Taiwan; it has also been applied to smaller extents in subregions of Australia, Mexico (Mexicali), and the United States (e.g., Pennsylvania).

Economic properties

Efficiency

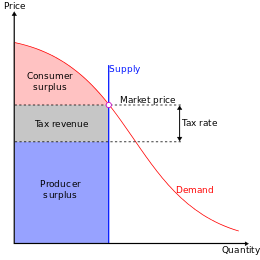

A supply and demand diagram showing the effects of land value taxation. As the supply of land is fixed, the burden of the tax falls entirely on the land owner. There is no change in the rental price and quantity transacted, and no deadweight loss.

Most taxes distort economic decisions and suppress beneficial economic activity.[13] LVT is payable regardless of how well or poorly land is actually used. Because the supply of land is essentially fixed,

land rents depend on what tenants are prepared to pay, rather than on

landlord expenses, preventing landlords from passing LVT to tenants.

The direct beneficiaries of incremental improvements to the area

surrounding a site are the land's occupants. Such improvements shift

tenants' demand curve to the right. Landlords benefit from price

competition among tenants; the only direct effect of LVT in this case is

to reduce the amount of social benefit that is privately captured as

land price by titleholders.

LVT is said to be justified for economic reasons because it does not deter production, distort markets, or otherwise create deadweight loss. Land value tax can even have negative deadweight loss (social benefits), particularly when land use improves. Nobel Prize-winner William Vickrey believed that

"removing almost all business taxes, including property taxes on improvements, excepting only taxes reflecting the marginal social cost of public services rendered to specific activities, and replacing them with taxes on site values, would substantially improve the economic efficiency of the jurisdiction."

A positive relationship of LVT and market efficiency is predicted by economic theory and has been observed in practice. Fred Foldvary

stated that the tax encourages landowners to develop vacant/underused

land or to sell it. He claimed that because LVT deters speculative land

holding, dilapidated inner city areas return to productive use, reducing the pressure to build on undeveloped sites and so reducing urban sprawl. For example, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in the United States has taxed land at a rate six times that on improvements since 1975. This policy was credited by mayor Stephen R. Reed with reducing the number of vacant structures in downtown Harrisburg from around 4,200 in 1982 to fewer than 500.

LVT is arguably an ecotax because it discourages the waste of prime locations, which are a finite resource. LVT is an efficient tax to collect because unlike labour and capital, land cannot be hidden or relocated. Many urban planners claim that LVT is an effective method to promote transit-oriented development.

Real estate values

The value of land is related to the value it can provide over time. This value can be measured by the ground rent that a piece of land can rent for on the market. The present value

of ground-rent is the basis for land prices. A land value tax (LVT)

will reduce the ground rent received by the landlord, and thus will

decrease the price of land, holding all else constant. The rent charged

for land may also decrease as a result of efficiency gains if

speculators stop hoarding unused land.

Real estate bubbles direct savings towards rent seeking activities rather than other investments and can contribute to recessions.

Advocates claim that LVT reduces the speculative element in land

pricing, thereby leaving more money for productive capital investment.

At sufficiently high levels, land value tax would cause real

estate prices to fall by removing land rents that would otherwise become

'capitalized' into the price of real estate. It also encourages

landowners to sell or relinquish titles to locations that they are not

using. This might cause some landowners, especially pure landowners, to

resist high land value tax rates. Landowners often possess significant

political influence, so this may explain the limited spread of land

value taxes so far.

Tax incidence

A land value tax has progressive tax effects, in that it is paid by the owners of valuable land who tend to be the rich, and since the amount of land is fixed, the tax burden cannot be passed on as higher rents or lower wages to tenants, consumers or workers.

Practical issues

Several practical issues are involved in the implementation of a land value tax. Most notably, it must be:

- Calculated fairly and accurately

- High enough to raise sufficient revenue without causing land abandonment

- Billed to the correct person or business entity

Assessment/appraisal

Levying a land value tax is straightforward, requiring only a

valuation of the land and a title register. Value assessment can be

difficult in practice. In a 1796 United States Supreme Court opinion, Justice William Paterson said that leaving the valuation process up to assessors would cause bureaucratic complexities, as well as non-uniform assessments. Murray Rothbard later raised similar concerns, claiming that no government can fairly assess value, and that this can only be determined by a free market.

Compared to modern day property tax evaluations, land valuations involve fewer variables and have smoother gradients than valuations that include improvements. This is due to variation of building style, quality and size between lots. Modern statistical techniques have eased the process; in the 1960s and 1970s, multivariate analysis was introduced as an assessment means.

Usually, such a valuation process commences with a measurement of the

most and least valuable land within the taxation area. A few sites of

intermediate value are then identified and used as "landmark" values.

Other values are filled in between the landmark values. The data is then

collated in a database and linked to a unique property reference

number, "smoothed" and mapped using a geographic information system

(GIS). Thus, even if the initial valuation is difficult, once the

system is in use, successive valuations become easier. Although still

easily distorted by corrupt politicians through the excuse of the

complex coding.

Revenue

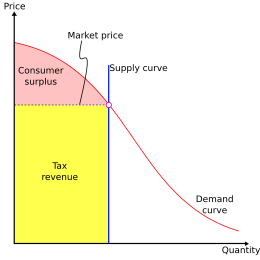

In

this case, land is taxed at 100% of its value, eliminating the

landowner surplus completely. The ownership of land becomes worthless

except to those who value it higher than market rents.

In the context of land value taxation as a single tax (replacing all other taxes), some have argued that LVT alone cannot raise enough revenues. However, the presence of other taxes can reduce land values and hence the amount of revenue that can be raised from them. The Physiocrats

argued that all taxes are ultimately at the expense of land rental

values. Most modern LVT systems function alongside other taxes and thus

only reduce their impact without removing them. Land taxes that are

higher than the rental surplus (the full land rent for that time period) would result in landowner abandonment.

Title

In some countries, LVT is impractical because of uncertainty regarding land titles and established land ownership and tenure.

For instance a parcel of grazing land may be communally owned by

village inhabitants and administered by village elders. The land in

question would need to be held in a trust or similar body for taxation

purposes. If the government cannot accurately define ownership

boundaries and ascertain the proper owners, it cannot know from whom to

collect the tax. The lack of clear titles is found in many developing

countries.

In African countries with imperfect land registration, boundaries may

be poorly surveyed and the owner can be unknown. LVT proponents argue

that such owners can be made to identify themselves under penalty of

losing the land.

Incentives

Speculation

The owner of a vacant lot in a thriving city must still pay a tax and

would rationally perceive the property as a financial liability,

encouraging him/her to put the land to use in order to cover the tax.

LVT removes financial incentives to hold unused land solely for price

appreciation, making more land available for productive uses. Land value

tax creates an incentive to convert these sites to more intensive

private uses or into public purposes.

Incidence

The

selling price of a good that is fixed in supply, such as land,

decreases if it is taxed. By contrast, the price of manufactured goods

can rise in response to increased taxes, because the higher price

reduces the number of units that are made. The price increase is how the

maker passes along some part of the tax to consumers.

However, if the revenue from LVT is used to reduce other taxes or to

provide valuable public investment, it can cause land prices to rise as a

result of higher productivity, by more than the amount that LVT

removed.

Land tax incidence

rests completely upon landlords, although business sectors that provide

services to landlords are indirectly impacted. In some economies, 80

percent of bank lending finances real estate, with a large portion of

that for land. Reduced demand for land speculation might reduce the amount of circulating bank credit.

While owners cannot charge higher rent to compensate for LVT, removing other taxes may increase rents.

Land use

Assuming constant demand, an increase in constructed space decreases

the cost of improvements to land such as houses. Shifting property taxes

from improvements to land encourages development. Infill of

underutilized urban space is one common practice to reduce urban sprawl.

Collection

LVT is less vulnerable to tax evasion, since land cannot be concealed or moved overseas and titles are easily identified, as they are registered with the public.

Land value assessments are usually considered public information, which

is available upon request. Transparency reduces tax evasion.

Ethics

Land acquires a scarcity

value owing to the competing needs for space. The value of land

generally owes nothing to the landowner and everything to the

surroundings. LVT supporters claim that the value of land depends on the

community.

Religion

In religious terms, it has been claimed that land is God's gift to mankind. For example, the Roman Catholic Church as part of its "universal destination of goods" principle asserts:

Everyone knows that the Fathers of the Church laid down the duty of the rich toward the poor in no uncertain terms. As St. Ambrose put it: "You are not making a gift of what is yours to the poor man, but you are giving him back what is his. You have been appropriating things that are meant to be for the common use of everyone. The earth belongs to everyone, not to the rich."

— Pope Paul VI, Populorum Progressio (1967)

In addition, the Church maintains that political authority has the

right and duty to regulate, including the right to tax, the legitimate

exercise of the right to ownership for the sake of the common good.

Equity

Everybody works but the vacant lot – Henry George

LVT considers the effect on land value of location, and of

improvements made to neighbouring land, such as proximity to roads and

public works. LVT is the purest implementation of the public finance

principle known as value capture.

A public works

project can increase land values and thus increase LVT revenues.

Arguably, public improvements should be paid for by the landowners who

benefit from them. Thus, LVT captures the value of socially created wealth, allowing a reduction in tax on privately created (non-land) wealth.

LVT generally is a progressive tax, with those of greater means paying more, in that land ownership is correlated to incomes and landlords cannot shift the tax burden onto tenants. LVT generally reduces economic inequality, removes incentives to misuse real estate, and reduces the vulnerability of economies to property bubbles and their collapse.

History

Pre-modern

Land value taxation began after the introduction of agriculture. It was originally based on crop yield. This early version of the tax required simply sharing the yield at the time of the harvest, on a yearly basis.

Aryan sages

of ancient India claimed that land should be held in common and that

unfarmed land should produce the same tax as productive land. "The earth

...is common to all beings enjoying the fruit of their own labour; it

belongs...to all alike"; therefore, "there should be left some for

everyone". Apastamba

said "If any person holding land does not exert himself and hence bears

no produce, he shall, if rich, be made to pay what ought to have been

produced".

Mencius

was a Chinese philosopher (around 300 BCE) who advocated for the

elimination of taxes and tariffs, to be replaced by the public

collection of urban land rent: "In the market-places, charge land-rent,

but don't tax the goods."

During the Middle-Ages, in the West, the first regular and permanent land tax system was based on a unit of land known as the hide.

The hide was originally an amount of land sufficient to support a

household, but later became subject to a land tax known as "geld".

Physiocrats

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, one of the leading physiocrats

The physiocrats were a group of economists who believed that the wealth of nations was derived solely from the value of land agriculture or land development. Before the Industrial Revolution, this was approximately correct. Physiocracy is one of the "early modern" schools of economics. Physiocrats called for the abolition of all existing taxes, completely free trade and a single tax on land. They did not distinguish between the intrinsic value of land and ground rent. Their theories originated in France and were most popular during the second half of the 18th century. The movement was particularly dominated by Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) and François Quesnay (1694–1774). It influenced contemporary statesmen, such as Charles Alexandre de Calonne. The Physiocrats were highly influential in the early history of land value taxation in the United States.

Radical Movement

A participant in the Radical Movement, Thomas Paine contended in his Agrarian Justice pamphlet that all citizens should be paid 15 pounds

at age 21 "as a compensation in part for the loss of his or her natural

inheritance by the introduction of the system of landed property." "Men

did not make the earth. It is the value of the improvements only, and

not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes

to the community a ground rent for the land which he holds." This proposal was the origin of the citizen's dividend advocated by Geolibertarianism. Thomas Spence advocated a similar proposal except that the land rent would be distributed equally each year regardless of age.

Classical economists

Adam Smith, in his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations,

first rigorously analyzed the effects of a land value tax, pointing out

how it would not hurt economic activity, and how it would not raise

contract rents.

Ground-rents are a still more proper subject of taxation than the rent of houses. A tax upon ground-rents would not raise the rents of houses. It would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent, who acts always as a monopolist, and exacts the greatest rent which can be got for the use of his ground. More or less can be got for it according as the competitors happen to be richer or poorer, or can afford to gratify their fancy for a particular spot of ground at a greater or smaller expense. In every country the greatest number of rich competitors is in the capital, and it is there accordingly that the highest ground-rents are always to be found. As the wealth of those competitors would in no respect be increased by a tax upon ground-rents, they would not probably be disposed to pay more for the use of the ground. Whether the tax was to be advanced by the inhabitant, or by the owner of the ground, would be of little importance. The more the inhabitant was obliged to pay for the tax, the less he would incline to pay for the ground; so that the final payment of the tax would fall altogether upon the owner of the ground-rent.

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Chapter 2, Article I: Taxes upon the Rent of Houses

Henry George

Henry George in 1865

Henry George (2 September 1839 – 29 October 1897) was perhaps the most famous advocate of recovering land rents for public purposes. An American journalist, politician and political economist, he advocated a "Single Tax" on land that would eliminate the need for all other taxes. In his best-selling work Progress and Poverty (1879), Henry George

argued that because the value of land depends on natural qualities

combined with the economic activity of communities, including public

investments, the economic rent of land was the best source of tax revenue.

This book significantly influenced land taxation in the United States

and other countries, including Denmark, which continues 'grundskyld'

(Ground Duty) as a key component of its tax system. The philosophy that natural resource rents should be captured by society is now often known as Georgism. Its relevance to public finance is underpinned by the Henry George theorem.

Meiji Restoration

After the 1868 Meiji Restoration in Japan, Land Tax Reform

was undertaken. A land value tax was implemented beginning in 1873. By

1880 initial problems with valuation and rural opposition had been

overcome and rapid industrialisation began.

Liberal and Labour Parties in the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, LVT was an important part of the platform of the Liberal Party during the early part of the twentieth century: David Lloyd George and H. H. Asquith proposed "to free the land that from this very hour is shackled with the chains of feudalism." It was also advocated by Winston Churchill early in his career. The modern Liberal Party (not to be confused with the Liberal Democrats, who are the heir to the earlier Liberal Party and who offer some support for the idea) remains committed to a local form of land value taxation, as do the Green Party of England and Wales and the Scottish Green Party.

The 1931 Labour budget included a land value tax, but before it

came into force it was repealed by the Conservative-dominated National

Government that followed shortly after.

An attempt at introducing site value taxation in the administrative County of London was made by the local authority under the leadership of Herbert Morrison

in the 1938–9 Parliament, called the London Rating (Site Values) Bill.

Although it failed, it detailed legislation for the implementation of a

system of land value taxation using annual value assessment.

After 1945, the Labour Party

adopted the policy, against substantial opposition, of collecting

"development value": the increase in land price arising from planning

consent. This was one of the provisions of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, but it was repealed when the Labour government lost power in 1951.

Senior Labour figures in recent times have advocated an LVT, notably Andy Burnham in his 2010 leadership campaign, former Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn and Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell.

Republic of China

The Republic of China was one of the first countries to implement a Land Value Tax, it being part of its constitution. Sun Yat-Sen would learn about LVT from the Kiautschou Bay concession, which had successful implementation of LVT, bringing increased wealth and financial stability to the colony. The Republic of China would go on to implement LVT in farms at first, later implementing it in the urban areas due to its success.

Modern economists

Alfred Marshall

argued in favour of a "fresh air rate", a tax to be charged to urban

landowners and ‘'levied on that value of urban land that is caused by

the concentration of population'’.

That ‘'general rate'’ should have ‘'to be spent on breaking out small

green spots in the midst of dense industrial districts, and on the

preservation of large green areas between different towns and between

different suburbs which are tending to coalesce'’. This idea influenced

Marshall's pupil Arthur Pigou's ideas on taxing negative externalities.

Paul Samuelson

supported a land value tax. "Our ideal society finds it essential to

put a rent on land as a way of maximizing the total consumption

available to the society. ...Pure land rent is in the nature of a

'surplus' which can be taxed heavily without distorting production

incentives or efficiency. A land value tax can be called 'the useful tax

on measured land surplus'."

Milton Friedman

stated: "There's a sense in which all taxes are antagonistic to free

enterprise – and yet we need taxes. ...So the question is, which are the

least bad taxes? In my opinion the least bad tax is the property tax on

the unimproved value of land, the Henry George argument of many, many

years ago."

Michael Hudson

is a proponent for taxing rent, especially land rent.".... politically,

taxing economic rent has become the bête noire of neoliberal globalism.

It is what property owners and rentiers fear most of all, as land,

subsoil resources and natural monopolies

far exceed industrial capital in magnitude. What appears in the

statistics at first glance as "profit" turns out upon examination to be

Ricardian or "economic" rent."

Paul Krugman

agreed that a land value tax is efficient, however he disputed whether

it should be considered a single tax, as he believed it would not be

enough alone, excluding taxes on natural resource rents and other

Georgist taxes, to fund a welfare state. "Believe it or not, urban

economics models actually do suggest that Georgist taxation would be the

right approach at least to finance city growth. But I would just say: I

don’t think you can raise nearly enough money to run a modern welfare

state by taxing land [only]."

Joseph Stiglitz, articulating the Henry George theorem

wrote that, "Not only was Henry George correct that a tax on land is

nondistortionary, but in an equilitarian society ... tax on land raises

just enough revenue to finance the (optimally chosen) level of

government expenditure."

Rick Falkvinge

has proposed a "Simplified taxless state" where the state is said to

own all the land it can defend from other states, and may lease this

land to people at market rates.

Implementation

Australia

Land

taxes in Australia are levied by the states, and generally apply to

land holdings only within a particular state. The exemption thresholds

vary, as do the tax rates and other rules.

In New South Wales,

the state land tax exempts farmland and principal residences and there

is a tax threshold. Determination of land value for tax purposes is the

responsibility of the Valuer-General. In Victoria,

the land tax threshold is $250,000 on the total value of all Victorian

property owned by a person as at 31 December of each year, and taxed at a

progressive rate. The principal residence, primary production land and

land used by a charity are exempt from land tax. In Tasmania

the threshold is $25,000 and the audit date is 1 July. Between $25,000

and $350,000 the tax rate is 0.55% and over $350,000 it is 1.5%. In Queensland, the threshold for individuals is $600,000 and $350,000 for other entities, and the audit date is 30 June. In South Australia the threshold is $332,000 and taxed at a progressive rate, the audit date is 30 June.

By revenue, property taxes represent 4.5% of total taxation in Australia. A government report in 1986 for Brisbane, Queensland advocated a land tax.

The Henry Tax Review of 2010 commissioned by the federal government recommended that state governments replace stamp duty

with land value tax. The review proposed multiple marginal rates and

that most agricultural land would be in the lowest band with a rate of

zero. Only the Australian Capital Territory moved to adopt this system and planned to reduce stamp duty by 5% and raise land tax by 5% for each of twenty years.

United States

Common property taxes include land value, which usually has a

separate assessment. Thus, land value taxation already exists in many

jurisdictions. Some jurisdictions have attempted to rely more heavily on

it. In Pennsylvania

certain cities raised the tax on land value while reducing the tax on

improvement/building/structure values. For example, the city of Altoona adopted a property tax that solely taxes land value in 2002 but repealed the tax in 2016.

In the late 19th century followers of Henry George founded a single tax colony at Fairhope, Alabama.

Although the colony, now a nonprofit corporation, still holds land in

the area and collects a relatively small ground rent, the land is

subject to state and local property taxes.

Hong Kong

Government rent in Hong Kong, formerly the crown rent, is levied in addition to Rates.

For properties that are located in the New Territories (including New

Kowloon), or located in the rest of the territory and whose land grant

was recorded after 27 May 1985, government rent is levied at 3% of the

rateable rental value.

Canada

Land

value taxes were common in Western Canada at the turn of the twentieth

century. In Vancouver LVT became the sole form of municipal taxation in

1910 under the leadership of mayor, Louis D. Taylor.

Gary B. Nixon (2000) stated that the rate never exceeded 2% of land

value, too low to prevent the speculation that led directly to the 1913

real estate crash. All Canadian provinces later taxed improvements.

Estonia

Estonia

levies a land value tax which is used to fund local municipalities. It

is a state level tax, but 100% of the revenue is used to fund Local

Councils. The rate is set by the Local Council within the limits of

0.1–2.5%. It is one of the most important sources of funding for

municipalities.

The land value tax is levied on the value of the land only,

improvements are not considered. Very few exemptions are considered on

the land tax and even public institutions are subject to the land value

tax. Land that is the site of a church is exempt, but other land held by

religious institutions is not exempt. The tax has contributed to a high rate (~90%) of owner-occupied residences within Estonia, compared to a rate of 67.4% in the United States.

Kenya

Kenya's LVT

history dates to at least 1972, shortly after it achieved independence.

Local governments must tax land value, but are required to seek

approval from the central government for rates that exceed 4 percent.

Buildings were not taxed in Kenya as of 2000. The central government is

legally required to pay municipalities for the value of land it

occupies. Kelly claimed that maybe as a result of this land reform,

Kenya became the only stable country in its region. As of late 2014, the city of Nairobi was still taxing only land values, although a tax on improvements had been proposed.

Namibia

A land value taxation on rural land was introduced in Namibia, with the primary intention of improving land use.

Singapore

Singapore

owns the majority of its land which it leases for 99-year terms. In

addition, Singapore also taxing development uplift at around 70%. These

two sources of revenue fund most of Singapore's new infrastructure.

Taiwan

As of 2010, land value taxes and land value increment taxes accounted for 8.4% of total government revenue in Taiwan.

Mexico

The capital city of Baja California, Mexicali, has had a Land Value Tax since the 1990s when it became the first locality in Mexico to implement such a tax.

Russia

In 1990, several economists wrote to then President Mikhail Gorbachev suggesting that Russia adopt LVT; its failure to do so was argued as causal in the rise of the Oligarchs.

Currently, Russia has a very modest Land Value tax of 0.3% on

residential, agricultural and utilities lands as well as a 1.5% tax for

other types of land.

Countries with active discussion

China

China's Real Rights Law contains provisions founded on LVT analysis.

Ireland

In 2010 the government of Ireland announced that it would introduce an LVT, beginning in 2013. However following a 2011 change in government, a property value tax was introduced instead (see Local property tax (Ireland)).

New Zealand

After

decades of a modest land value tax, New Zealand abolished the tax in

1990. Discussions remain as to whether or not to bring it back (see Land taxes in New Zealand). Earlier Georgist politicians included Patrick O'Regan and Tom Paul (who was Vice-President of the New Zealand Land Values League).

United Kingdom

In September 1908 Prime Minister Lloyd George instructed McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty,

to build more Dreadnought battleships in the financial year to the

following April, the ships were to be financed by a proposed new Land

Tax. Lloyd George believed relating national defence to land tax would

both provoke the opposition of the House of Lords and rally the people

round a simple emotive issue. The House of Lords, composed of wealthy land owners, rejected the Budget in November 1909, leading to a constitutional crisis.

LVT was on the UK statute books briefly in 1931, introduced by Philip Snowden's 1931 budget, strongly supported by prominent LVT campaigner Andrew MacLaren MP. MacLaren lost his seat at the next election (1931) and the act was repealed, MacLaren tried again with a private member's bill in 1937; it was rejected 141 to 118.

Labour Land Campaign activities within the Labour party and the

broader Labour movement for "a more equitable distribution of the Land

Values that are created by the whole community" through LVT. Its

membership includes members of the British Labour Party, Trade Unions

and Cooperatives and individuals. The Liberal Democrats' ALTER (Action for Land Taxation and Economic Reform) aims

to improve the understanding of and support for Land Value Taxation amongst members of the Liberal Democrats; to encourage all Liberal Democrats to promote and campaign for this policy as part of a more sustainable and just resource based economic system in which no one is enslaved by poverty; and to cooperate with other bodies, both inside and outside the Liberal Democrat Party, who share these objectives.

The Green Party "favour moving to a system of Land Value Tax, where

the level of taxation depends on the rental value of the land

concerned."

A course in "Economics with Justice" with a strong foundation in LVT are offered at the School of Economic Science, which was founded by Andrew MacLaren MP and has historical links with the Henry George Foundation.

Scotland

Since the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, interest in adopting a land value tax in Scotland has grown.

In February 1998, the Scottish Office of the British Government launched a public consultation process on land reform.

A survey of the public response found that: "excluding the responses of

the lairds and their agents, reckoned as likely prejudiced against the

measure, 20% of all responses favoured the land tax" (12% in grand

total, without the exclusions).

The government responded by announcing "a comprehensive economic

evaluation of the possible impact of moving to a land value taxation

basis". However, no measure was adopted.

In 2000 the Parliament's Local Government Committee's inquiry into local government finance explicitly included LVT, but the final report omitted any mention.

In 2003 the Scottish Parliament passed a resolution: "That the Parliament notes recent studies by the Scottish Executive

and is interested in building on them by considering and investigating

the contribution that land value taxation could make to the cultural,

economic, environmental and democratic renaissance of Scotland."

In 2004 a letter of support was sent from members of the Scottish Parliament to the organisers and delegates of the IU's 24th international conference—including members of the Scottish Green Party, Scottish Socialist Party and the Scottish National Party.

The policy was considered the 2006 Scottish Local Government Finance Review whose 2007 Report

concluded that "although land value taxation meets a number of our

criteria, we question whether the public would accept the upheaval

involved in radical reform of this nature, unless they could clearly

understand the nature of the change and the benefits involved.... We

considered at length the many positive features of a land value tax

which are consistent with our recommended local property tax [LPT],

particularly its progressive nature." However, "[h]aving considered both

rateable value and land value as the basis for taxation, we concur with

Layfield (UK Committee of Inquiry, 1976) who recommended that any local

property tax should be based on capital values."

In 2009, Glasgow City Council resolved to introduce LVT: "the idea could become the blueprint for Scotland’s future local taxation" The Council agreed to

a "long term move to a local property tax / land value tax hybrid tax":

Its Local Taxation Working Group stated that simple [non-hybrid] land

value taxation should itself "not be discounted as an option for local

taxation reform: it potentially holds many benefits and addresses many

existing concerns".

Policy interest

In Zimbabwe, government coalition partners the Movement for Democratic Change adopted LVT.

Belgium

Ethiopia

Republic of South Africa

Thailand

Hungary