A scanning electron microscope image of a single human lymphocyte

The adaptive immune system, also referred as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminates pathogens by preventing their growth. The acquired immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies found in vertebrates (the other being the innate immune system).

Acquired immunity creates immunological memory

after an initial response to a specific pathogen, and leads to an

enhanced response to subsequent encounters with that pathogen. This

process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination. Like the innate system, the acquired system includes both humoral immunity components and cell-mediated immunity components.

Google Ngram

of "acquired immunity " vs. "adaptive immunity". The peak for

"adaptive" in the 1960s reflects its introduction to immunology by Robert A. Good and use by colleagues; the explosive increase in the 1990s was correlated with the use of the phrase "innate immunity".

Unlike the innate immune system, the acquired immune system is highly

specific to a particular pathogen. Acquired immunity can also provide

long-lasting protection; for example, someone who recovers from measles

is now protected against measles for their lifetime. In other cases it

does not provide lifetime protection; for example, chickenpox.

The acquired system response destroys invading pathogens and any toxic

molecules they produce. Sometimes the acquired system is unable to

distinguish harmful from harmless foreign molecules; the effects of this

may be hayfever, asthma or any other allergy.

Antigens are any substances that elicit the acquired immune response (whether adaptive or maladaptive to the organism).

The cells that carry out the acquired immune response are white

blood cells known as lymphocytes. Two main activities—antibody responses

and cell mediated immune response—are also carried out by two different

lymphocytes (B cells and T cells). In antibody responses, B cells are

activated to secrete antibodies,

which are proteins also known as immunoglobulins. Antibodies travel

through the bloodstream and bind to the foreign antigen causing it to

inactivate, which does not allow the antigen to bind to the host.

In acquired immunity, pathogen-specific receptors

are "acquired" during the lifetime of the organism (whereas in innate

immunity pathogen-specific receptors are already encoded in the germline).

The acquired response is called "adaptive" because it prepares the

body's immune system for future challenges (though it can actually also

be maladaptive when it results in autoimmunity).

The system is highly adaptable because of somatic hypermutation (a process of accelerated somatic mutations), and V(D)J recombination (an irreversible genetic recombination

of antigen receptor gene segments). This mechanism allows a small

number of genes to generate a vast number of different antigen

receptors, which are then uniquely expressed on each individual lymphocyte. Since the gene rearrangement leads to an irreversible change in the DNA of each cell, all progeny (offspring) of that cell inherit genes that encode the same receptor specificity, including the memory B cells and memory T cells that are the keys to long-lived specific immunity.

A theoretical framework explaining the workings of the acquired immune system is provided by immune network theory. This theory, which builds on established concepts of clonal selection, is being applied in the search for an HIV vaccine.

Naming

The term "adaptive" was first used by Robert Good

in reference to antibody responses in frogs as a synonym for "acquired

immune response" in 1964. Good acknowledged he used the terms as

synonyms but explained only that he "preferred" to use the term

"adaptive". He might have been thinking of the then not implausible

theory of antibody formation in which antibodies were plastic and could

adapt themselves to the molecular shape of antigens, and/or to the

concept of "adaptive enzymes" as described by Monod

in bacteria, that is, enzymes whose expression could be induced by

their substrates. The phrase was used almost exclusively by Good and

his students and a few other immunologists working with marginal

organisms until the 1990s when it became widely used in tandem with the

term "innate immunity" which became a popular subject after the

discovery of the Toll receptor system in Drosophila, a previously

marginal organism for the study of immunology. The term "adaptive" as

used in immunology is problematic as acquired immune responses can be

both adaptive and maladaptive in the physiological sense. Indeed, both

acquired and innate immune responses can be both adaptive and

maladaptive in the evolutionary sense. Most textbooks today, following

the early use by Janeway, use "adaptive" almost exclusively and noting in glossaries that the term is synonymous with "acquired".

The classic sense of "acquired immunity" came to mean, since Tonegawa's

discovery, "antigen-specific immunity mediated by somatic gene

rearrangements that create clone-defining antigen receptors". In the

last decade, the term "adaptive" has been increasingly applied to

another class of immune response not so-far associated with somatic gene

rearrangements. These include expansion of natural killer (NK) cells

with so-far unexplained specificity for antigens, expansion of NK cells

expressing germ-line encoded receptors, and activation of other innate

immune cells to an activated state that confers a short-term "immune

memory". In this sense, "adaptive immunity" more closely resembles the

concept of "activated state" or "heterostasis", thus returning in sense

to the physiological sense of "adaptation" to environmental changes.

Functions

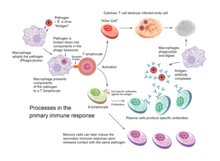

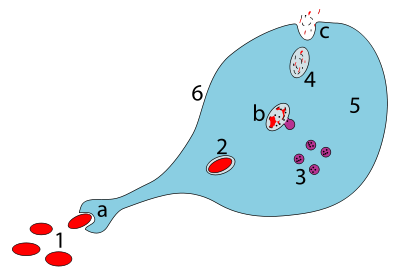

Overview of the processes involved in the primary immune response

Acquired immunity is triggered in vertebrates when a pathogen evades

the innate immune system and (1) generates a threshold level of antigen

and (2) generates "stranger" or "danger" signals activating dendritic cells.

The major functions of the acquired immune system include:

- Recognition of specific "non-self" antigens in the presence of "self", during the process of antigen presentation.

- Generation of responses that are tailored to maximally eliminate specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells.

- Development of immunological memory, in which pathogens are "remembered" through memory B cells and memory T cells.

In humans, it takes 4-7 days for the adaptive immune system to mount a significant response.

Lymphocytes

The cells of the acquired immune system are T and B lymphocytes; lymphocytes are a subset of leukocyte. B cells and T cells

are the major types of lymphocytes. The human body has about 2 trillion

lymphocytes, constituting 20–40% of white blood cells (WBCs); their

total mass is about the same as the brain or liver. The peripheral blood contains 2% of circulating lymphocytes; the rest move within the tissues and lymphatic system.

B cells and T cells are derived from the same multipotent hematopoietic stem cells, and are morphologically indistinguishable from one another until after they are activated. B cells play a large role in the humoral immune response, whereas T cells are intimately involved in cell-mediated immune responses. In all vertebrates except Agnatha, B cells and T cells are produced by stem cells in the bone marrow.

T progenitors migrate from the bone marrow to the thymus

where they are called thymocytes and where they develop into T cells.

In humans, approximately 1–2% of the lymphocyte pool recirculates each

hour to optimize the opportunities for antigen-specific lymphocytes to

find their specific antigen within the secondary lymphoid tissues.

In an adult animal, the peripheral lymphoid organs contain a mixture of B

and T cells in at least three stages of differentiation:

- naive B and naive T cells (cells that have not matured), left the bone marrow or thymus, have entered the lymphatic system, but have yet to encounter their cognate antigen,

- effector cells that have been activated by their cognate antigen, and are actively involved in eliminating a pathogen.

- memory cells – the survivors of past infections.

Antigen presentation

Acquired immunity relies on the capacity of immune cells to distinguish between the body's own cells and unwanted invaders.

The host's cells express "self" antigens.

These antigens are different from those on the surface of bacteria or

on the surface of virus-infected host cells ("non-self" or "foreign"

antigens). The acquired immune response is triggered by recognizing

foreign antigen in the cellular context of an activated dendritic cell.

With the exception of non-nucleated cells (including erythrocytes), all cells are capable of presenting antigen through the function of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Some cells are specially equipped to present antigen, and to prime naive T cells. Dendritic cells, B-cells, and macrophages

are equipped with special "co-stimulatory" ligands recognized by

co-stimulatory receptors on T cells, and are termed professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

Several T cells subgroups can be activated by professional APCs,

and each type of T cell is specially equipped to deal with each unique

toxin or microbial pathogen. The type of T cell activated, and the type

of response generated, depends, in part, on the context in which the APC

first encountered the antigen.

Exogenous antigens

Antigen presentation stimulates T cells to become either "cytotoxic" CD8+ cells or "helper" CD4+ cells.

Dendritic cells engulf exogenous pathogens, such as bacteria, parasites or toxins in the tissues and then migrate, via chemotactic

signals, to the T cell-enriched lymph nodes. During migration,

dendritic cells undergo a process of maturation in which they lose most

of their ability to engulf other pathogens, and develop an ability to

communicate with T-cells. The dendritic cell uses enzymes to chop the pathogen into smaller pieces, called antigens.

In the lymph node, the dendritic cell displays these non-self antigens

on its surface by coupling them to a receptor called the major histocompatibility complex, or MHC (also known in humans as human leukocyte antigen

(HLA)). This MHC: antigen complex is recognized by T-cells passing

through the lymph node. Exogenous antigens are usually displayed on MHC class II molecules, which activate CD4+T helper cells.

Endogenous antigens

Endogenous

antigens are produced by intracellular bacteria and viruses replicating

within a host cell. The host cell uses enzymes to digest virally

associated proteins, and displays these pieces on its surface to T-cells

by coupling them to MHC. Endogenous antigens are typically displayed on

MHC class I molecules, and activate CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. With the exception of non-nucleated cells (including erythrocytes), MHC class I is expressed by all host cells.

T lymphocytes

CD8+ T lymphocytes and cytotoxicity

Cytotoxic T cells (also known as TC, killer T cell, or cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte (CTL)) are a sub-group of T cells that induce the death of

cells that are infected with viruses (and other pathogens), or are

otherwise damaged or dysfunctional.

Naive cytotoxic T cells are activated when their T-cell receptor

(TCR) strongly interacts with a peptide-bound MHC class I molecule. This

affinity depends on the type and orientation of the antigen/MHC

complex, and is what keeps the CTL and infected cell bound together. Once activated, the CTL undergoes a process called clonal selection,

in which it gains functions and divides rapidly to produce an army of

“armed” effector cells. Activated CTL then travels throughout the body

searching for cells that bear that unique MHC Class I + peptide.

When exposed to these infected or dysfunctional somatic cells, effector CTL release perforin and granulysin: cytotoxins that form pores in the target cell's plasma membrane, allowing ions and water to flow into the infected cell, and causing it to burst or lyse. CTL release granzyme, a serine protease encapsulated in a granule that enters cells via pores to induce apoptosis

(cell death). To limit extensive tissue damage during an infection, CTL

activation is tightly controlled and in general requires a very strong

MHC/antigen activation signal, or additional activation signals provided

by "helper" T-cells (see below).

On resolution of the infection, most effector cells die and phagocytes clear them away—but a few of these cells remain as memory cells.

On a later encounter with the same antigen, these memory cells quickly

differentiate into effector cells, dramatically shortening the time

required to mount an effective response.

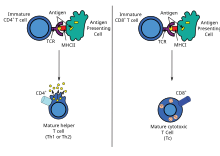

Helper T-cells

The

T lymphocyte activation pathway. T cells contribute to immune defenses

in two major ways: some direct and regulate immune responses; others

directly attack infected or cancerous cells.

CD4+ lymphocytes, also called "helper" T cells, are immune response

mediators, and play an important role in establishing and maximizing the

capabilities of the acquired immune response.

These cells have no cytotoxic or phagocytic activity; and cannot kill

infected cells or clear pathogens, but, in essence "manage" the immune

response, by directing other cells to perform these tasks.

Helper T cells express T cell receptors (TCR) that recognize

antigen bound to Class II MHC molecules. The activation of a naive

helper T-cell causes it to release cytokines, which influences the

activity of many cell types, including the APC (Antigen-Presenting Cell)

that activated it. Helper T-cells require a much milder activation

stimulus than cytotoxic T cells. Helper T cells can provide extra

signals that "help" activate cytotoxic cells.

Th1 and Th2: helper T cell responses

Classically, two types of effector CD4+

T helper cell responses can be induced by a professional APC,

designated Th1 and Th2, each designed to eliminate different types of

pathogens. The factors that dictate whether an infection triggers a Th1

or Th2 type response are not fully understood, but the response

generated does play an important role in the clearance of different

pathogens.

The Th1 response is characterized by the production of Interferon-gamma, which activates the bactericidal activities of macrophages, and induces B cells to make opsonizing (marking for phagocytosis) and complement-fixing antibodies, and leads to cell-mediated immunity. In general, Th1 responses are more effective against intracellular pathogens (viruses and bacteria that are inside host cells).

The Th2 response is characterized by the release of Interleukin 5, which induces eosinophils in the clearance of parasites. Th2 also produce Interleukin 4, which facilitates B cell isotype switching. In general, Th2 responses are more effective against extracellular bacteria, parasites including helminths and toxins. Like cytotoxic T cells, most of the CD4+ helper cells die on resolution of infection, with a few remaining as CD4+ memory cells.

Increasingly, there is strong evidence from mouse and human-based scientific studies of a broader diversity in CD4+ effector T helper cell subsets. Regulatory T (Treg) cells, have been identified as important negative regulators of adaptive immunity as they limit and suppresses

the immune system to control aberrant immune responses to

self-antigens; an important mechanism in controlling the development of

autoimmune diseases. Follicular helper T (Tfh) cells are another distinct population of effector CD4+ T cells that develop from naive T cells post-antigen activation. Tfh cells are specialized in helping B cell humoral immunity as they are uniquely capable of migrating to follicular B cells

in secondary lymphoid organs and provide them positive paracrine

signals to enable the generation and recall production of high-quality affinity-matured antibodies. Similar to Tregs, Tfh cells also play a role in immunological tolerance

as an abnormal expansion of Tfh cell numbers can lead to unrestricted

autoreactive antibody production causing severe systemic autoimmune

disorders.

The relevance of CD4+ T helper cells is highlighted during an HIV infection. HIV is able to subvert the immune system by specifically attacking the CD4+

T cells, precisely the cells that could drive the clearance of the

virus, but also the cells that drive immunity against all other

pathogens encountered during an organism's lifetime.

Gamma delta T cells

Gamma delta T cells (γδ T cells) possess an alternative T cell receptor

(TCR) as opposed to CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells and share characteristics

of helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells. Like

other 'unconventional' T cell subsets bearing invariant TCRs, such as CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells,

γδ T cells exhibit characteristics that place them at the border

between innate and acquired immunity. On one hand, γδ T cells may be

considered a component of adaptive immunity in that they rearrange TCR

genes via V(D)J recombination, which also produces junctional diversity,

and develop a memory phenotype. On the other hand, however, the various

subsets may also be considered part of the innate immune system where a

restricted TCR or NK receptors may be used as a pattern recognition receptor. For example, according to this paradigm, large numbers of Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells respond within hours to common molecules produced by microbes, and highly restricted intraepithelial Vδ1 T cells respond to stressed epithelial cells.

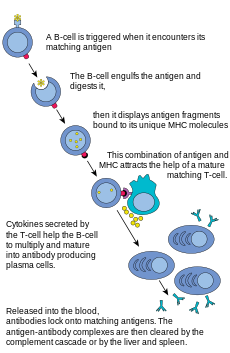

B lymphocytes and antibody production

The

B lymphocyte activation pathway. B cells function to protect the host

by producing antibodies that identify and neutralize foreign objects

like bacteria and viruses.

B Cells are the major cells involved in the creation of antibodies that circulate in blood plasma and lymph, known as humoral immunity.

Antibodies (also known as immunoglobulin, Ig), are large Y-shaped

proteins used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign

objects. In mammals, there are five types of antibody: IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM,

differing in biological properties; each has evolved to handle

different kinds of antigens. Upon activation, B cells produce

antibodies, each of which recognize a unique antigen, and neutralizing

specific pathogens.

Antigen and antibody binding would cause five different protective mechanisms:

- Agglutination: Reduces number of infectious units to be dealt with

- Activation of complement: Cause inflammation and cell lysis

- Opsonization: Coating antigen with antibody enhances phagocytosis

- Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity: Antibodies attached to target cell cause destruction by macrophages, eosinophils, and NK cells

- Neutralization: Blocks adhesion of bacteria and viruses to mucosa

Like the T cell, B cells express a unique B cell receptor (BCR), in

this case, a membrane-bound antibody molecule. All the BCR of any one

clone of B cells recognizes and binds to only one particular antigen. A

critical difference between B cells and T cells is how each cell "sees"

an antigen. T cells recognize their cognate antigen in a processed form –

as a peptide in the context of an MHC molecule, whereas B cells recognize antigens in their native form. Once a B cell encounters its cognate (or specific) antigen (and receives additional signals from a helper T cell (predominately Th2 type)), it further differentiates into an effector cell, known as a plasma cell.

Plasma cells

are short-lived cells (2–3 days) that secrete antibodies. These

antibodies bind to antigens, making them easier targets for phagocytes,

and trigger the complement cascade. About 10% of plasma cells survive to become long-lived antigen-specific memory B cells.

Already primed to produce specific antibodies, these cells can be

called upon to respond quickly if the same pathogen re-infects the host,

while the host experiences few, if any, symptoms.

Alternative systems

In jawless vertebrates

Primitive jawless vertebrates, such as the lamprey and hagfish,

have an adaptive immune system that shows 3 different cell lineages,

each sharing a common origin with B cells, αβ T cells, and innate-like

γΔ T cells. Instead of the classical antibodies and T cell receptors, these animals possess a large array of molecules called variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs for short) that, like the antigen receptors of jawed vertebrates, are produced from only a small number (one or two) of genes. These molecules are believed to bind pathogenic antigens in a similar way to antibodies, and with the same degree of specificity.

In insects

For a long time it was thought that insects and other invertebrates possess only innate immune system. However, in recent years some of the basic hallmarks of adaptive immunity have been discovered in insects. Those traits are immune memory and specificity. Although the hallmarks are present the mechanisms are different from those in vertebrates.

Immune memory in insects was discovered through the phenomenon of

priming. When insects are exposed to non-lethal dose or heat killed bacteria

they are able to develop a memory of that infection that allows them to

withstand otherwise lethal dose of the same bacteria they were exposed

to before. Unlike in vertebrates, insects do not possess cells specific for adaptive immunity. Instead those mechanisms are mediated by hemocytes.

Hemocytes function similarly to phagocytes and after priming they are

able to more effectively recognize and engulf the pathogen. It was also shown that it is possible to transfer the memory into offspring. For example, in honeybees if the queen is infected with bacteria then the newly born workers have enhanced abilities in fighting with the same bacteria. Other experimental model based on red flour beetle also showed pathogen specific primed memory transfer into offspring from both mothers and fathers.

Most commonly accepted theory of the specificity is based on Dscam gene. Dscam gene also known as Down syndrome cell adhesive molecule is a gene that contains 3 variable Ig domains. Those domains can be alternatively spliced reaching high numbers of variations.

It was shown that after exposure to different pathogens there are

different splice forms of dscam produced. After the animals with

different splice forms are exposed to the same pathogen only the

individuals with the splice form specific for that pathogen survive.

Other mechanisms supporting the specificity of insect immunity is RNA interference (RNAi). RNAi is a form of antiviral immunity with high specificity. It has several different pathways that all end with the virus being unable to replicate. One of the pathways is siRNA

in which long double stranded RNA is cut into pieces that serve as

templates for protein complex Ago2-RISC that finds and degrades

complementary RNA of the virus. MiRNA pathway in cytoplasm binds to Ago1-RISC complex and functions as a template for viral RNA degradation. Last one is piRNA where small RNA binds to the Piwi protein family and controls transposones and other mobile elements. Despite the research the exact mechanisms responsible for immune priming and specificity in insects are not well described.

Immunological memory

When B cells and T cells are activated some become memory B cells and some memory T cells.

Throughout the lifetime of an animal these memory cells form a database

of effective B and T lymphocytes. Upon interaction with a previously

encountered antigen, the appropriate memory cells are selected and

activated. In this manner, the second and subsequent exposures to an

antigen produce a stronger and faster immune response. This is

"adaptive" in the sense that the body's immune system prepares itself

for future challenges, but is "maladaptive" of course if the receptors

are autoimmune. Immunological memory can be in the form of either passive short-term memory or active long-term memory.

Passive memory

Passive memory is usually short-term, lasting between a few days and several months. Newborn infants

have had no prior exposure to microbes and are particularly vulnerable

to infection. Several layers of passive protection are provided by the

mother. In utero, maternal IgG is transported directly across the placenta, so that, at birth, human babies have high levels of antibodies, with the same range of antigen specificities as their mother. Breast milk

contains antibodies (mainly IgA) that are transferred to the gut of the

infant, protecting against bacterial infections, until the newborn can

synthesize its own antibodies.

This is passive immunity

because the fetus does not actually make any memory cells or

antibodies: It only borrows them. Short-term passive immunity can also

be transferred artificially from one individual to another via

antibody-rich serum.

Active memory

In

general, active immunity is long-term and can be acquired by infection

followed by B cell and T cell activation, or artificially acquired by

vaccines, in a process called immunization.

Immunization

Historically,

infectious disease has been the leading cause of death in the human

population. Over the last century, two important factors have been

developed to combat their spread: sanitation and immunization. Immunization (commonly referred to as vaccination)

is the deliberate induction of an immune response, and represents the

single most effective manipulation of the immune system that scientists

have developed. Immunizations are successful because they utilize the immune system's natural specificity as well as its inducibility.

The principle behind immunization is to introduce an antigen,

derived from a disease-causing organism, that stimulates the immune

system to develop protective immunity against that organism, but that

does not itself cause the pathogenic effects of that organism. An antigen (short for antibody generator), is defined as any substance that binds to a specific antibody and elicits an adaptive immune response.

Most viral vaccines are based on live attenuated viruses, whereas many bacterial vaccines are based on acellular components of microorganisms, including harmless toxin components.

Many antigens derived from acellular vaccines do not strongly induce an

adaptive response, and most bacterial vaccines require the addition of adjuvants that activate the antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system to enhance immunogenicity.

Immunological diversity

An

antibody is made up of two heavy chains and two light chains. The

unique variable region allows an antibody to recognize its matching

antigen.

Most large molecules, including virtually all proteins and many polysaccharides, can serve as antigens. The parts of an antigen that interact with an antibody molecule or a lymphocyte receptor, are called epitopes,

or antigenic determinants. Most antigens contain a variety of epitopes

and can stimulate the production of antibodies, specific T cell

responses, or both.

A very small proportion (less than 0.01%) of the total lymphocytes

are able to bind to a particular antigen, which suggests that only a few

cells respond to each antigen.

For the acquired response to "remember" and eliminate a large

number of pathogens the immune system must be able to distinguish

between many different antigens,

and the receptors that recognize antigens must be produced in a huge

variety of configurations, in essence one receptor (at least) for each

different pathogen that might ever be encountered. Even in the absence

of antigen stimulation, a human can produce more than 1 trillion

different antibody molecules.

Millions of genes would be required to store the genetic information

that produces these receptors, but, the entire human genome contains

fewer than 25,000 genes.

Myriad receptors are produced through a process known as clonal selection.

According to the clonal selection theory, at birth, an animal randomly

generates a vast diversity of lymphocytes (each bearing a unique

antigen receptor) from information encoded in a small family of genes.

To generate each unique antigen receptor, these genes have undergone a

process called V(D)J recombination, or combinatorial diversification,

in which one gene segment recombines with other gene segments to form a

single unique gene. This assembly process generates the enormous

diversity of receptors and antibodies, before the body ever encounters

antigens, and enables the immune system to respond to an almost

unlimited diversity of antigens.

Throughout an animal's lifetime, lymphocytes that can react against the

antigens an animal actually encounters are selected for action—directed

against anything that expresses that antigen.

Note that the innate and acquired portions of the immune system

work together, not in spite of each other. The acquired arm, B, and T

cells couldn't function without the innate system input. T cells are

useless without antigen-presenting cells to activate them, and B cells

are crippled without T cell help. On the other hand, the innate system

would likely be overrun with pathogens without the specialized action of

the adaptive immune response.

Acquired immunity during pregnancy

The

cornerstone of the immune system is the recognition of "self" versus

"non-self". Therefore, the mechanisms that protect the human fetus

(which is considered "non-self") from attack by the immune system, are

particularly interesting. Although no comprehensive explanation has

emerged to explain this mysterious, and often repeated, lack of

rejection, two classical reasons may explain how the fetus is tolerated.

The first is that the fetus occupies a portion of the body protected by

a non-immunological barrier, the uterus, which the immune system does not routinely patrol.

The second is that the fetus itself may promote local immunosuppression

in the mother, perhaps by a process of active nutrient depletion. A more modern explanation for this induction of tolerance is that specific glycoproteins expressed in the uterus during pregnancy suppress the uterine immune response (see eu-FEDS).

During pregnancy in viviparous mammals (all mammals except Monotremes), endogenous retroviruses

(ERVs) are activated and produced in high quantities during the

implantation of the embryo. They are currently known to possess

immunosuppressive properties, suggesting a role in protecting the embryo

from its mother's immune system. Also, viral fusion proteins cause the formation of the placental syncytium to limit exchange of migratory cells between the developing embryo and the body of the mother (something an epithelium

can't do sufficiently, as certain blood cells specialize to insert

themselves between adjacent epithelial cells). The immunodepressive

action was the initial normal behavior of the virus, similar to HIV. The

fusion proteins were a way to spread the infection to other cells by

simply merging them with the infected one (HIV does this too). It is

believed that the ancestors of modern viviparous mammals evolved after

an infection by this virus, enabling the fetus to survive the immune

system of the mother.

The human genome project found several thousand ERVs classified into 24 families.

Immune network theory

A theoretical framework explaining the workings of the acquired immune system is provided by immune network theory, based on interactions between idiotypes (unique molecular features of one clonotype, i.e. the unique set of antigenic determinants

of the variable portion of an antibody) and 'anti-idiotypes' (antigen

receptors that react with the idiotype as if it were a foreign antigen).

This theory, which builds on the existing clonal selection hypothesis and since 1974 has been developed mainly by Niels Jerne and Geoffrey W. Hoffmann, is seen as being relevant to the understanding of the HIV pathogenesis and the search for an HIV vaccine.

Stimulation of adaptive immunity

One

of the most interesting developments in biomedical science during the

past few decades has been elucidation of mechanisms mediating innate

immunity. One set of innate immune mechanisms is humoral, such as complement activation. Another set comprises pattern recognition receptors such as toll-like receptors, which induce the production of interferons and other cytokines increasing resistance of cells such as monocytes to infections. Cytokines produced during innate immune responses are among the activators of adaptive immune responses.

Antibodies exert additive or synergistic effects with mechanisms of

innate immunity. Unstable HbS clusters Band-3, a major integral red cell

protein;

antibodies recognize these clusters and accelerate their removal by

phagocytic cells. Clustered Band 3 proteins with attached antibodies

activate complement, and complement C3 fragments are opsonins recognized

by the CR1 complement receptor on phagocytic cells.

A population study has shown that the protective effect of the

sickle-cell trait against falciparum malaria involves the augmentation

of acquired as well as innate immune responses to the malaria parasite,

illustrating the expected transition from innate to acquired immunity.

Repeated malaria infections strengthen acquired immunity and broaden its effects against parasites expressing different surface antigens.

By school age most children have developed efficacious adaptive

immunity against malaria. These observations raise questions about

mechanisms that favor the survival of most children in Africa while

allowing some to develop potentially lethal infections.

In malaria, as in other infections,

innate immune responses lead into, and stimulate, adaptive immune

responses. The genetic control of innate and acquired immunity is now a

large and flourishing discipline.

Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses limit malaria parasite

multiplication, and many cytokines contribute to the pathogenesis of

malaria as well as to the resolution of infections.

Evolution

The

acquired immune system, which has been best-studied in mammals,

originated in jawed fish approximately 500 million years ago. Most of

the molecules, cells, tissues, and associated mechanisms of this system

of defense are found in cartilaginous fishes. Lymphocyte

receptors, Ig and TCR, are found in all jawed vertebrates. The most

ancient Ig class, IgM, is membrane-bound and then secreted upon

stimulation of cartilaginous fish B cells. Another isotype, shark IgW,

is related to mammalian IgD. TCRs, both α/β and γ/δ, are found in all

animals from gnathostomes to mammals. The organization of gene segments that undergo gene rearrangement

differs in cartilaginous fishes, which have a cluster form as compared

to the translocon form in bony fish to mammals. Like TCR and Ig, the MHC

is found only in jawed vertebrates. Genes involved in antigen processing and presentation, as well as the class I and class II genes, are closely linked within the MHC of almost all studied species.

Lymphoid cells can be identified in some pre-vertebrate deuterostomes (i.e., sea urchins). These bind antigen with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of the innate immune system. In jawless fishes, two subsets of lymphocytes use variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) for antigen binding. Diversity is generated by a cytosine deaminase-mediated rearrangement of LRR-based DNA segments. There is no evidence for the recombination-activating genes (RAGs) that rearrange Ig and TCR gene segments in jawed vertebrates.

The evolution of the AIS, based on Ig, TCR, and MHC molecules, is

thought to have arisen from two major evolutionary events: the transfer

of the RAG transposon (possibly of viral origin) and two whole genome duplications.

Though the molecules of the AIS are well-conserved, they are also

rapidly evolving. Yet, a comparative approach finds that many features

are quite uniform across taxa. All the major features of the AIS arose

early and quickly. Jawless fishes have a different AIS

that relies on gene rearrangement to generate diverse immune receptors

with a functional dichotomy that parallels Ig and TCR molecules. The innate immune system, which has an important role in AIS activation, is the most important defense system of invertebrates and plants.

Types of acquired immunity

Immunity

can be acquired either actively or passively. Immunity is acquired

actively when a person is exposed to foreign substances and the immune

system responds. Passive immunity is when antibodies are transferred

from one host to another. Both actively acquired and passively acquired

immunity can be obtained by natural or artificial means.

- Naturally Acquired Active Immunity – when a person is naturally exposed to antigens, becomes ill, then recovers.

- Naturally Acquired Passive Immunity – involves a natural transfer of antibodies from a mother to her infant. The antibodies cross the woman's placenta to the fetus. Antibodies can also be transferred through breast milk with the secretions of colostrum.

- Artificially Acquired Active Immunity – is done by vaccination (introducing dead or weakened antigen to the host's cell).

- Artificially Acquired Passive Immunity – This involves the introduction of antibodies rather than antigens to the human body. These antibodies are from an animal or person who is already immune to the disease.

| Naturally acquired | Artificially acquired |

|---|---|

| Active – Antigen enters the body naturally | Active – Antigens are introduced in vaccines. |

| Passive – Antibodies pass from mother to fetus via placenta or infant via the mother's milk. | Passive – Preformed antibodies in immune serum are introduced by injection. |