Rum display in a liquor store (United States, 2009)

Government House rum, manufactured by the Virgin Islands Company distillery in St. Croix, circa 1941

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Most rums are produced in Caribbean and American countries, but also in other sugar producing countries, such as the Philippines and India.

Rums are produced in various grades. Light rums are commonly used in cocktails, whereas "golden" and "dark" rums were typically consumed straight or neat, iced ("on the rocks"),

or used for cooking, but are now commonly consumed with mixers. Premium

rums are made to be consumed either straight or iced.

Rum plays a part in the culture of most islands of the West Indies as well as the Maritime provinces and Newfoundland, in Canada. The beverage has famous associations with the Royal Navy (where it was mixed with water or beer to make grog) and piracy (where it was consumed as bumbo). Rum has also served as a popular medium of economic exchange, used to help fund enterprises such as slavery, organized crime, and military insurgencies (e.g., the American Revolution and Australia's Rum Rebellion).

Etymology

The Mount Gay Rum visitors centre in Barbados claims to be the world's oldest active rum company, with earliest confirmed deed from 1703.

The origin of the word "rum" is unclear. The most widely accepted

hypothesis is that it is related to "rumbullion" a beverage made from

boiling sugar cane stalks, or possibly "rumbustion," which was a slang word for "uproar" or "tumult"; a noisy uncontrollable exuberance, though the origin of those words and the nature of the relationship are unclear. Both words surfaced in English about the same time as rum did (1651 for "rumbullion", and 1661 "rum").

There have been various other theories:

- It is often connected to the British slang adjective "rum", meaning "high quality", and indeed the collocation "rum booze" is attested. Given the harshness of early rum, this is unlikely.

- That it is related to ramboozle and rumfustian, popular British drinks of the mid-17th century. However, neither was made with rum, but rather eggs, ale, wine, sugar, and various spices.

- That it comes from the large drinking glasses used by Dutch seamen known as rummers, from the Dutch word roemer, a drinking glass.

- Other theories consider it to be short for iterum, Latin for "again; a second time", or arôme, French for aroma.

Regardless of the original source, the name was already in common use by 1654, when the General Court of Connecticut ordered the confiscations of "whatsoever Barbados liquors, commonly called rum, kill devil and the like". A short time later in May 1657, the General Court of Massachusetts also decided to make illegal the sale of strong liquor "whether knowne by the name of rumme, strong water, wine, brandy, etc".

In current usage, the name used for a rum is often based on its place of origin.

For rums from places mostly in Latin America where Spanish is spoken, the word ron is used. A ron añejo ("aged rum") is a premium spirit.

Rhum is the term that typically distinguishes rum made

from fresh sugar cane juice from rum made from molasses in

French-speaking locales like Martinique. A rhum vieux ("old rum") is an aged French rum that meets several other requirements.

Some of the many other names for rum are Nelson's blood, kill-devil, demon water, pirate's drink, navy neaters, and Barbados water.

A version of rum from Newfoundland is referred to by the name screech, while some low-grade West Indies rums are called tafia.

History

Origins

Vagbhata, an Indian Ayurvedic

physician (7th century AD) "[advised] a man to drink unvitiated liquor

like rum and wine, and mead mixed with mango juice 'together with

friends.’” Shidhu, a drink produced by fermentation and distillation of

sugarcane juice, is mentioned in other Sanskrit texts.[13]

Maria Dembinska states that the King, Peter I of Cyprus,

also called Pierre I de Lusignan (9 October 1328 – 17 January 1369),

brought rum with him as a gift for the other royal dignitaries at the Congress of Kraków, held in 1364. This is plausible given the position of Cyprus as a significant producer of sugar in the Middle Ages,

although the alcoholic sugar drink named rum by Dembinska may not have

resembled modern distilled rums very closely. Dembinska also suggests

Cyprus rum was often drunk mixed with an almond milk drink, also

produced in Cyprus, called soumada.

Another early rum-like drink is brum. Produced by the Malay people, that beverage dates back thousands of years.

Marco Polo also recorded a 14th-century account of a "very good wine of sugar" that was offered to him in the area that became modern-day Iran.

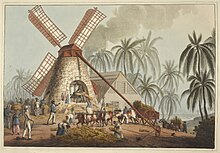

The first distillation of rum in the Caribbean took place on the sugarcane plantations there in the 17th century.

Plantation slaves discovered that molasses, a by-product

of the sugar refining process, could be fermented into alcohol. Then,

distillation of these alcoholic byproducts concentrated the alcohol, and

removed some impurities, producing the first modern rums. Tradition

suggests this type of rum first originated on the island of Nevis.

A 1651 document from Barbados stated, "The chief fuddling they make in

the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar

canes distilled, a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor." However, in the decade of the 1620s, rum production was also recorded in Brazil and many historians believe that rum found its way to Barbados along with sugarcane and its cultivation methods from Brazil.

A liquid identified as rum has been found in a tin bottle found on the Swedish warship Vasa, which sank in 1628.

By the late 17th century rum had replaced French brandy as the exchange-alcohol of choice in the triangle trade. Canoemen and guards on the African side of the trade, who had previously been paid in brandy, were now paid in rum.

Colonial North America

Pirates carrying rum to shore to purchase slaves as depicted in The Pirates Own Book by Charles Ellms

After development of rum in the Caribbean, the drink's popularity spread to Colonial North America. To support the demand for the drink, the first rum distillery in the British colonies of North America was set up in 1664 on Staten Island. Boston, Massachusetts had a distillery three years later. The manufacture of rum became early Colonial New England's largest and most prosperous industry. New England became a distilling center due to the technical, metalworking and cooperage skills and abundant lumber; the rum produced there was lighter, more like whiskey. Much of the rum was exported, distillers in Newport, R.I. even made an extra strong rum specifically to be used as a slave currency. Rhode Island rum even joined gold as an accepted currency in Europe for a period of time. While New England triumphed on price and consistency Europeans still viewed the best rums as coming from the Caribbean. Estimates of rum consumption in the American colonies before the American Revolutionary War had every man, woman, or child drinking an average of 3 imperial gallons (14 l) of rum each year.

In the 18th century ever increasing demands for sugar, molasses,

rum, and slaves led to a feedback loop which intensified the triangle

trade.

When France banned the production of rum in their New World possessions

to end the domestic competition with brandy, New England distillers

were then able to undercut producers in the British Caribbean by buying

cut rate molasses from French sugar plantations. Outcry from the British

rum industry led to the Molasses Act

of 1733 which levied a prohibitive tax on molasses imported into

Britain's North American colonies from foreign countries or colonies.

Rum at this time accounted for approximately 80% of New England’s

exports and paying the duty would have put the distilleries out of

business: as a result, both compliance with and enforcement of the act

were minimal. Strict enforcement of the Molasses Act’s successor, the Sugar Act, in 1764 may have helped cause the American Revolution. In the slave trade, rum was also used as a medium of exchange. For example, the slave Venture Smith (whose history was later published) had been purchased in Africa, for four gallons of rum plus a piece of calico.

The popularity of rum continued after the American Revolution; George Washington insisting on a barrel of Barbados rum at his 1789 inauguration.

Rum started to play an important role in the political system;

candidates attempted to influence the outcome of an election through

their generosity with rum. The people would attend the hustings to see

which candidate appeared more generous. The candidate was expected to

drink with the people to show he was independent and truly a republican.

Eventually the restrictions on sugar imports from the British

islands of the Caribbean, combined with the development of American whiskeys, led to a decline in the drink's popularity in North America.

Wrens during World War II serving rum to a sailor from a tub inscribed "The King God Bless Him" - Robert Sargent Austin

Rum grog

Rum's association with piracy began with British privateers'

trading in the valuable commodity. Some of the privateers became

pirates and buccaneers, with a continuing fondness for rum; the

association between the two was only strengthened by literary works such

as Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island.

The association of rum with the Royal Navy began in 1655, when the British fleet captured the island of Jamaica. With the availability of domestically produced rum, the British changed the daily ration of liquor given to seamen from French brandy to rum.

Navy rum was originally a blend mixed from rums produced in the West Indies.

It was initially supplied at a strength of 100 degrees (UK) proof, 57%

alcohol by volume (ABV), as that was the only strength that could be

tested (by the gunpowder test) before the invention of the hydrometer. The term "Navy strength" is used in modern Britain to specify spirits bottled at 57% ABV.

While the ration was originally given neat, or mixed with lime

juice, the practice of watering down the rum began around 1740. To help

minimize the effect of the alcohol on his sailors, Admiral Edward Vernon had the rum ration watered, producing a mixture that became known as grog. Many believe the term was coined in honour of the grogram cloak Admiral Vernon wore in rough weather.

The Royal Navy continued to give its sailors a daily rum ration, known

as a "tot", until the practice was abolished on 31 July 1970.

Today, a tot (totty) of rum is still issued on special occasions, using an order to "splice the mainbrace",

which may only be given by the Queen, a member of the royal family or,

on certain occasions, the admiralty board in the UK, with similar

restrictions in other Commonwealth navies.

Recently, such occasions have included royal marriages or birthdays, or

special anniversaries. In the days of daily rum rations, the order to

"splice the mainbrace" meant double rations would be issued.

A legend involving naval rum and Horatio Nelson says that following his victory and death at the Battle of Trafalgar,

Nelson's body was preserved in a cask of rum to allow transportation

back to England. Upon arrival, however, the cask was opened and found to

be empty of rum. The [pickled] body was removed and, upon inspection,

it was discovered that the sailors had drilled a hole in the bottom of

the cask and drunk all the rum, hence the term "Nelson's blood" being

used to describe rum. It also serves as the basis for the term tapping the admiral

being used to describe surreptitiously sucking liquor from a cask

through a straw. The details of the story are disputed, as many

historians claim the cask contained French brandy, whilst others claim instead the term originated from a toast to Admiral Nelson.

Variations of the story, involving different notable corpses, have been

in circulation for many years. The official record states merely that

the body was placed in "refined spirits" and does not go into further

detail.

The Royal New Zealand Navy was the last naval force to give sailors a free daily tot of rum. The Royal Canadian Navy

still gives a rum ration on special occasions; the rum is usually

provided out of the commanding officer's fund, and is 150 proof (75%).

The order to "splice the mainbrace" (i.e. take rum) can be given by the

Queen as commander-in-chief, as occurred on 29 June 2010, when she gave

the order to the Royal Canadian Navy as part of the celebration of their

100th anniversary.

Rum was also occasionally consumed mixed with gunpowder, either after the proof was tested—proof spirit, when mixed with gunpowder, would just support combustion (57% ABV)—or to seal a vow or show loyalty to a rebellion.

Colonial Australia

Beenleigh Rum Distillery, on the banks of the Albert River near Brisbane, Queensland, circa 1912

Rum became an important trade good in the early period of the colony of New South Wales.

The value of rum was based upon the lack of coinage among the

population of the colony, and due to the drink's ability to allow its

consumer to temporarily forget about the lack of creature comforts

available in the new colony. The value of rum was such that convict

settlers could be induced to work the lands owned by officers of the New

South Wales Corps. Due to rum's popularity among the settlers, the

colony gained a reputation for drunkenness, though their alcohol

consumption was less than levels commonly consumed in England at the

time.

Australia was so far away from Britain that the convict colony,

established in 1788, faced severe food shortages, compounded by poor

conditions for growing crops and the shortage of livestock. Eventually

it was realized that it might be cheaper for India, instead of Britain, to supply the settlement of Sydney. By 1817, two out of every three ships which left Sydney went to Java or India, and cargoes from Bengal

fed and equipped the colony. Casks of Bengal Rum (which was reputed to

be stronger than Jamaican Rum, and not so sweet) were brought back in

the depths of nearly every ship from India. The cargoes were floated

ashore clandestinely before the ships docked, by the British Marines

regiment who controlled the sales. It was against the direct orders of

the governors, who had ordered the searching of every docking ship.

Britons living in India grew wealthy through sending ships to Sydney

"laden half with rice and half with bad spirits".

Rum was intimately involved in the only military takeover of an Australian government, known as the Rum Rebellion. When William Bligh

became governor of the colony, he attempted to remedy the perceived

problem with drunkenness by outlawing the use of rum as a medium of

exchange. In response to Bligh's attempt to regulate the use of rum, in

1808, the New South Wales Corps marched with fixed bayonets to

Government House and placed Bligh under arrest. The mutineers continued

to control the colony until the arrival of Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810.

Categorization

Dividing

rum into meaningful groupings is complicated because no single standard

exists for what constitutes rum. Instead, rum is defined by the varying

rules and laws of the nations producing the spirit. The differences in

definitions include issues such as spirit proof, minimum ageing, and even naming standards.

Mexico requires rum be aged a minimum of eight months; the

Dominican Republic, Panama and Venezuela require two years. Naming

standards also vary. Argentina defines rums as white, gold, light, and

extra light. Grenada and Barbados uses the terms white, overproof, and matured, while the United States defines rum, rum liqueur, and flavored rum.

In Australia, rum is divided into dark or red rum (underproof known as

UP, overproof known as OP, and triple distilled) and white rum.

Despite these differences in standards and nomenclature, the

following divisions are provided to help show the wide variety of rums

produced.

Regional variations

The Bacardi building in Havana, Cuba

Within the Caribbean, each island or production area has a unique

style. For the most part, these styles can be grouped by the language

traditionally spoken. Due to the overwhelming influence of Puerto Rican

rum, most rum consumed in the United States is produced in the

"Spanish-speaking" style.

- English-speaking areas are known for darker rums with a fuller taste that retains a greater amount of the underlying molasses flavor. Rums from Bahamas, Antigua, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, Belize, Bermuda, Saint Kitts, the Demerara region of Guyana, and Jamaica are typical of this style. A version called "Rude Rum" or "John Crow Batty" is served in some places and it is reportedly much stronger in alcohol content being listed as one of the 10 strongest drinks in the world, while it might also contain other intoxicants. The term, denoting home made, strong rum, appears in New Zealand since at least the early 19th century.

- French-speaking areas are best known for their agricultural rums (rhum agricole). These rums, being produced exclusively from sugar cane juice, retain a greater amount of the original flavor of the sugar cane and are generally more expensive than molasses-based rums. Rums from Haiti, Guadeloupe and Martinique are typical of this style.

- Areas that had been formerly part of the Spanish Empire traditionally produce añejo rums with a fairly smooth taste. Rums from Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Venezuela are typical of this style. Rum from the U.S. Virgin Islands is also of this style. The Canary Islands produces a honey-based rum known as ron miel de Canarias which carries a protected geographical designation.

Cachaça

is a spirit similar to rum that is produced in Brazil. Some countries,

including the United States, classify cachaça as a type of rum. Seco, from Panama, is also a spirit similar to rum, but also similar to vodka since it is triple distilled.

Mexico produces a number of brands of light and dark rum, as well

as other less-expensive flavored and unflavored sugarcane-based

liquors, such as aguardiente de caña and charanda.

Aguardiente is also the name for unaged distilled cane spirit in some,

primarily Spanish-speaking countries, since their definition of rum

includes at least two years of ageing in wood.

A spirit known as aguardiente, distilled from molasses and often infused with anise, with additional sugarcane juice added after distillation, is produced in Central America and northern South America.

In West Africa, and particularly in Liberia, 'cane juice' (also known as Liberian rum or simply CJ within Liberia itself) is a cheap, strong spirit distilled from sugarcane, which can be as strong as 43% ABV (86 proof). A refined cane spirit has also been produced in South Africa since the 1950s, simply known as cane or "spook".

Within Europe, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, a similar spirit made from sugar beet is known as Tuzemak.

In Germany, a cheap substitute for genuine dark rum is called Rum-Verschnitt (literally: blended or "cut" rum). This drink is made of genuine dark rum (often high-ester rum from Jamaica), rectified spirit, and water. Very often, caramel coloring is used, too. The relative amount of genuine rum it contains can be quite low, since the legal minimum is at only 5%. In Austria, a similar rum called Inländerrum or domestic rum is available. However, Austrian Inländerrum is always a spiced rum, such as the brand Stroh; German Rum-Verschnitt, in contrast, is never spiced or flavored.

Grades

The

grades and variations used to describe rum depend on the location where a

rum was produced. Despite these variations, the following terms are

frequently used to describe various types of rum:

- Dark rums, also known by their particular colour, such as brown, black, or red rums, are classes a grade darker than gold rums. They are usually made from caramelized sugar or molasses. They are generally aged longer, in heavily charred barrels, giving them much stronger flavors than either light or gold rums, and hints of spices can be detected, along with a strong molasses or caramel overtone. They commonly provide substance in rum drinks, as well as colour. In addition, dark rum is the type most commonly used in cooking. Most dark rums come from areas such as Jamaica, Bahamas, Haiti, and Martinique.

- Flavored rums are infused with flavors of fruits, such as banana, mango, orange, pineapple, coconut, starfruit or lime. These are generally less than 40% ABV (80 proof). They mostly serve to flavor similarly-themed tropical drinks but are also often drunk neat or with ice. This infusion of flavors occurs after fermentation and distillation. Various chemicals are added to the alcohol to simulate the tastes of food.

- Gold rums, also called "amber" rums, are medium-bodied rums that are generally aged. These gain their dark colour from aging in wooden barrels (usually the charred, white oak barrels that are the byproduct of Bourbon whiskey). They have more flavor and are stronger-tasting than light rum, and can be considered midway between light rum and the darker varieties.

- Light rums, also referred to as "silver" or "white" rums, in general, have very little flavor aside from a general sweetness. Light rums are sometimes filtered after aging to remove any colour. The majority of light rums come from Puerto Rico. Their milder flavors make them popular for use in mixed drinks, as opposed to drinking them straight. Light rums are included in some of the most popular cocktails including the Mojito and the Daiquiri.

- Overproof rums are much higher than the standard 40% ABV (80 proof), with many as high as 75% (150 proof) to 80% (160 proof) available. Two examples are Bacardi 151 or Pitorro moonshine. They are usually used in mixed drinks.

- Premium rums, as with other sipping spirits such as Cognac and Scotch whisky, are in a special market category. These are generally from boutique brands that sell carefully produced and aged rums. They have more character and flavor than their "mixing" counterparts and are generally consumed straight.

- Spiced rums obtain their flavors through the addition of spices and, sometimes, caramel. Most are darker in colour, and based on gold rums. Some are significantly darker, while many cheaper brands are made from inexpensive white rums and darkened with caramel colour. Among the spices added are cinnamon, rosemary, absinthe/aniseed, pepper, cloves, and cardamom.

Production method

Unlike

some other spirits, rum has no defined production methods. Instead, rum

production is based on traditional styles that vary between locations

and distillers.

Fermentation

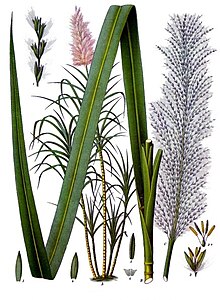

Sugarcane is harvested to make sugarcane juice and molasses.

Artisanal Rum distillery along the N7 road

Most rum is produced from molasses, which is made from sugarcane. A

rum's quality is dependent on the quality and variety of the sugar cane

that was used to create it. The sugar cane's quality depends on the soil

type and climate that it was grown in. Within the Caribbean, much of

this molasses is from Brazil.

A notable exception is the French-speaking islands, where sugarcane juice is the preferred base ingredient. In Brazil itself, the distilled alcoholic drink derived from cane juice is distinguished from rum and called cachaça.

Yeast

and water are added to the base ingredient to start the fermentation

process.

While some rum producers allow wild yeasts to perform the fermentation,

most use specific strains of yeast to help provide a consistent taste

and predictable fermentation time.

Dunder, the yeast-rich foam from previous fermentations, is the traditional yeast source in Jamaica.

"The yeast employed will determine the final taste and aroma profile,"

says Jamaican master blender Joy Spence.

Distillers that make lighter rums, such as Bacardi, prefer to use faster-working yeasts.

Use of slower-working yeasts causes more esters to accumulate during fermentation, allowing for a fuller-tasting rum.

Fermentation products like 2-ethyl-3-methyl butyric acid and esters like ethyl butyrate and ethyl hexanoate give rise to the sweet and fruitiness of rum.

Distillation

As with all other aspects of rum production, no standard method is used for distillation.

While some producers work in batches using pot stills, most rum production is done using column still distillation.

Pot still output contains more congeners than the output from column stills, so produces fuller-tasting rums.

Ageing and blending

Many countries require rum to be aged for at least one year. This ageing is commonly performed in used bourbon casks,

but may also be performed in other types of wooden casks or stainless

steel tanks. The ageing process determines the colour of the rum. When

aged in oak casks, it becomes dark, whereas rum aged in stainless steel

tanks remains virtually colourless.

Due to the tropical climate, common to most rum-producing areas,

rum matures at a much higher rate than is typical for whisky or brandy.

An indication of this higher rate is the angels' share, or amount of product lost to evaporation. While products aged in France or Scotland see about 2% loss each year, tropical rum producers may see as much as 10%.

After ageing, rum is normally blended to ensure a consistent flavour, the final step in the rum-making process. During blending, light rums may be filtered to remove any colour gained during ageing. For dark rums, caramel may be added for colour.

There have been attempts to match the molecular composition of aged rum in significantly shorter time spans with artificial aging using heat and light.

In cuisine

Besides rum punches, cocktails such as the Cuba libre and daiquiri have stories of their invention in the Caribbean. Tiki culture in the U.S. helped expand rum's horizons with inventions such as the mai tai and zombie. Other cocktails containing rum include the piña colada, a drink made popular in America by Rupert Holmes' song "Escape (The Piña Colada Song)", and the mojito. Cold-weather drinks made with rum include the rum toddy and hot buttered rum.

A number of local specialties also use rum, including Bermuda's Dark 'n' Stormy (Gosling's Black Seal rum with ginger beer), the Painkiller from the British Virgin Islands, and a New Orleans cocktail known as the Hurricane. Jagertee is a mixture of rum and black tea popular in colder parts of Central Europe and served on special occasions in the British Army, where it is called Gunfire. Ti' Punch, French Creole for "petit punch", is a traditional drink in parts of the French West Indies.

Rum may also be used as a base in the manufacture of liqueurs and syrups, such as falernum and most notably, Mamajuana.

Rum is used in a number of cooked dishes as a flavoring agent in items such as rum balls or rum cakes. It is commonly used to macerate fruit used in fruitcakes and is also used in marinades for some Caribbean dishes. Rum is also used in the preparation of rumtopf, bananas Foster and some hard sauces. Rum is sometimes mixed into ice cream, often with raisins, and in baking it is occasionally used in Joe Froggers, a type of cookie from New England.