Simple living encompasses a number of different voluntary practices to simplify one's lifestyle. These may include, for example, reducing one's possessions, generally referred to as minimalism, or increasing self-sufficiency. Simple living may be characterized by individuals being satisfied with what they have rather than want. Although asceticism generally promotes living simply and refraining from luxury and indulgence, not all proponents of simple living are ascetics. Simple living is distinct from those living in forced poverty, as it is a voluntary lifestyle choice.

Adherents may choose simple living for a variety of personal reasons, such as spirituality, health, increase in quality time for family and friends, work–life balance, personal taste, financial sustainability, frugality, sustainability or reducing stress. Simple living can also be a reaction to materialism and conspicuous consumption. Some cite socio-political goals aligned with the environmentalist, anti-consumerist or anti-war movements, including conservation, degrowth, deep ecology, and tax resistance.

History

Religious and spiritual

A number of religious and spiritual traditions encourage simple living. Early examples include the Śramaṇa traditions of Iron Age India, Gautama Buddha, and biblical Nazirites.

The biblical figure Jesus is said to have lived a simple life. He is said to have encouraged his disciples "to take nothing for their journey except a staff—no bread, no bag, no money in their belts—but to wear sandals and not put on two tunics."

Various notable individuals have claimed that spiritual inspiration led them to a simple living lifestyle, such as Benedict of Nursia, Francis of Assisi, Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy, Rabindranath Tagore, Albert Schweitzer, and Mahatma Gandhi.

Traditions of simple living stretch back to antiquity, finding resonance with leaders such as Laozi, Confucius, Zarathustra, Buddha, Jesus and Muhammed. These traditions were heavily influenced by both Mediterranean culture and Abrahamic ethics. Diogenes, a major figure in the ancient Greek philosophy of Cynicism, claimed that a simple life was necessary for virtue, and was said to have lived in a wine jar.

Plain people are Christian groups who have for centuries practised lifestyles in which some forms of wealth or technology are excluded for religious or philosophical reasons. Groups include the Shakers, Mennonites, Amish, Hutterites, Amana Colonies, Bruderhof, Old German Baptist Brethren, Harmony Society, and some Quakers. There is a Quaker belief called Testimony of simplicity that a person ought to live her or his life simply. Some tropes about complete rejection of technology in these groups are not accurate though. The Amish and other groups do use some modern technology, after assessing its impact on the community.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau strongly praised the simple life in many of his writings, especially in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750) and Discourse on Inequality (1754).

Secular

Epicureanism, based on the teachings of the Athens-based philosopher Epicurus, flourished from about the fourth century BC to the third century AD. Epicureanism upheld the untroubled life as the paradigm of happiness, made possible by carefully considered choices. Specifically, Epicurus pointed out that troubles entailed by maintaining an extravagant lifestyle tend to outweigh the pleasure of partaking in it. He therefore concluded that what is necessary for happiness, bodily comfort, and life itself should be maintained at minimal cost, while all things beyond what is necessary for these should either be tempered by moderation or completely avoided.

Henry David Thoreau, an American naturalist and author, is often considered to have made the classic secular statement advocating a life of simple and sustainable living in his book Walden (1854). Thoreau conducted a two-year experiment living a plain and simple life on the shores of Walden Pond.

In Victorian Britain, Henry Stephens Salt, an admirer of Thoreau, popularised the idea of "Simplification, the saner method of living". Other British advocates of the simple life included Edward Carpenter, William Morris, and the members of the "Fellowship of the New Life". Carpenter popularised the phrase the "Simple Life" in his essay Simplification of Life in his England's Ideal (1887).

C.R. Ashbee and his followers also practised some of these ideas, thus linking simplicity with the Arts and Crafts movement. British novelist John Cowper Powys advocated the simple life in his 1933 book A Philosophy of Solitude. John Middleton Murry and Max Plowman practised a simple lifestyle at their Adelphi Centre in Essex in the 1930s. Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh championed a "right simplicity" philosophy based on ruralism in some of his work.

George Lorenzo Noyes, a naturalist, mineralogist, development critic, writer, and artist, is known as the Thoreau of Maine. He lived a wilderness lifestyle, advocating through his creative work a simple life and reverence for nature. During the 1920s and 1930s, the Vanderbilt Agrarians of the Southern United States advocated a lifestyle and culture centered upon traditional and sustainable agrarian values as opposed to the progressive urban industrialism which dominated the Western world at that time.

Thorstein Veblen warned against the conspicuous consumption of the materialistic society with The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899); Richard Gregg coined the term "voluntary simplicity" in The Value of Voluntary Simplicity (1936). From the 1920s, a number of modern authors articulated both the theory and practice of living simply, among them Gandhian Richard Gregg, economists Ralph Borsodi and Scott Nearing, anthropologist-poet Gary Snyder, and utopian fiction writer Ernest Callenbach. E. F. Schumacher argued against the notion that "bigger is better" in Small Is Beautiful (1973); and Duane Elgin continued the promotion of the simple life in Voluntary Simplicity (1981). The Australian academic Ted Trainer practices and writes about simplicity, and established The Simplicity Institute at Pigface Point, some 20 km from the University of New South Wales to which it is attached. A secular set of nine values was developed with the Ethify Yourself project in Austria, having a simplified life style in mind and accompanied by an online book (2011). In the United States voluntary simplicity started to garner more public exposure through a movement in the late 1990s around a popular "simplicity" book, The Simple Living Guide by Janet Luhrs. Around the same time, minimalism (a similar movement) started to also show its light into the public eye.

Changing mindset

Living simply involves different lifestyle habits, and trying to achieve a simple living lifestyle is a long and gradual process. The idea of it may sound satisfying, but the essence of this practice is to recognize the essential things, implement changes, and do the changes repeatedly. Danny Dover, author of the book "The Minimalist Mindset", states ideas are simply just thoughts, but implementing and acting on these ideas in our own lives is what will make it habitual, and allowing a change in mindset. Leo Babauta believes finding beauty and joy in less, is what advocates the thought of "more is better" to be untrue. It is quality over quantity that minimalists prefer to follow. It is emphasized that we should value things that make us happy and are essential to us, rather than value the idea of just having things to have.

This mindset has spread among many individuals due to influences of other people living this lifestyle. Joshua Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus share their story of what they used to see life for. The constant additions that are never ending in this worlds are what drove their impulses to keep buying and filling this void of acceptance and approval. Realizing there was this emptiness of being able to get anything they want, there was no meaning behind what they had. This called for a change in mindset with what they see as important and truly valuable before they can begin any other practices or lifestyle habits.

Practices

Reducing consumption, work time, and possessions

Some people practice simple living by reducing consumption. By lowering expenditure on goods or services, the time spent earning money can be reduced. The time saved may be used to pursue other interests, or help others through volunteering. Some may use the extra free time to improve their quality of life, for example pursuing creative activities such as art and crafts. Developing a detachment from money has led some individuals, such as Suelo and Mark Boyle, to live with no money at all. Reducing expenses may also lead to increasing savings, which can lead to financial independence and the possibility of early retirement.

The 100 Thing Challenge is a grassroots movement to whittle down personal possessions to one hundred items, with the aim of de-cluttering and simplifying life. The small house movement includes individuals who chose to live in small, mortgage-free, low-impact dwellings, such as log cabins or beach huts.

Those who follow simple living may hold a different value over their homes. Joshua Becker suggests simplifying the place that they live for those who desire to live this lifestyle. He addresses the fact that the purpose of a home is a place for safety and belonging. Many get caught up over all of the space they have in their house and feel the need to buy stuff to fill it. This is something that must be reflected upon because it raises the question of if it is just pleasing to the eye, or if it is truly needed.

Increasing self-sufficiency

One way to simplify life is to get back-to-the-land and grow your own food, as increased self-sufficiency reduces dependency on money and the economy. Tom Hodgkinson believes the key to a free and simple life is to stop consuming and start producing. This is a sentiment shared by an increasing number of people, including those belonging to the millennial generation such as writer and eco blogger Jennifer Nini, who left the city to live off-grid, grow food, and "be a part of the solution; not part of the problem."

Forest gardening, developed by simple living adherent Robert Hart, is a low-maintenance plant-based food production system based on woodland ecosystems, incorporating fruit and nut trees, shrubs, herbs, vines and perennial vegetables. Hart created a model forest garden from a 0.12 acre orchard on his farm at Wenlock Edge in Shropshire.

The idea of food miles, the number of miles a given item of food or its ingredients has travelled between the farm and the table, is used by simple living advocates to argue for locally grown food. This is now gaining mainstream acceptance, as shown by the popularity of books such as The 100-Mile Diet, and Barbara Kingsolver's Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life. In each of these cases, the authors devoted a year to reducing their carbon footprint by eating locally.

City dwellers can also produce fresh home-grown fruit and vegetables in pot gardens or miniature indoor greenhouses. Tomatoes, lettuce, spinach, Swiss chard, peas, strawberries, and several types of herbs can all thrive in pots. Jim Merkel says that a person "could sprout seeds. They are tasty, incredibly nutritious, and easy to grow... We grow them in wide-mouthed mason jars with a square of nylon window screen screwed under a metal ring". Farmer Matt Moore spoke on this issue: "How does it affect the consumer to know that broccoli takes 105 days to grow ahead? [...] The supermarket mode is one of plenty — it's always stocked. And that changes our sense of time. How long it takes to grow food — that's removed in the marketplace. They don't want you to think about how long it takes to grow, because they want you to buy right now". One way to change this viewpoint is also suggested by Mr. Moore. He placed a video installation in the produce section of a grocery store that documented the length of time it took to grow certain vegetables. This aimed to raise awareness in people of the length of time actually needed for gardens.

The do it yourself ethic refers to the principle of undertaking necessary tasks oneself rather than having others, who are more skilled or experienced, complete them for you.

Reconsidering technology

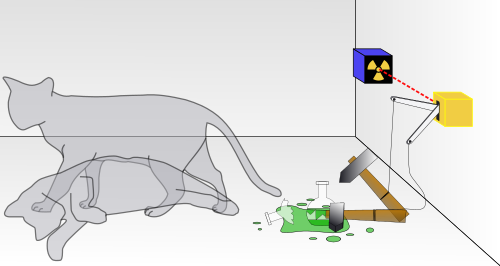

People who practice simple living have diverse views on the role of technology. The American political activist Scott Nearing was skeptical about how humanity would use new technology, citing destructive inventions such as nuclear weapons. Those who eschew modern technology are often referred to as Luddites or neo-Luddites. Although simple living is often a secular pursuit, it may still involve reconsidering personal definitions of appropriate technology, as Anabaptist groups such as the Amish or Mennonites have done.

Technological proponents see cutting-edge technologies as a way to make a simple lifestyle within mainstream culture easier and more sustainable. They argue that the internet can reduce an individual's carbon footprint through telecommuting and lower paper usage. Some have also calculated their energy consumption and have shown that one can live simply and in an emotionally satisfying way by using much less energy than is used in Western countries. Technologies they may embrace include computers, photovoltaic systems, wind and water turbines.

Technological interventions that appear to simplify living may actually induce side effects elsewhere or at a future point in time. Evgeny Morozov warns that tools like the internet can facilitate mass surveillance and political repression. The book Green Illusions identifies how wind and solar energy technologies have hidden side effects and can actually increase energy consumption and entrench environmental harms over time. Authors of the book Techno-Fix criticize technological optimists for overlooking the limitations of technology in solving agricultural problems.

Advertising is criticised for encouraging a consumerist mentality. Many advocates of simple living tend to agree that cutting out, or cutting down on, television viewing is a key ingredient in simple living. Some see the Internet, podcasting, community radio, or pirate radio as viable alternatives.

Simplifying diet

Another practice is the adoption of a simplified diet or a diet that may simplify domestic food production and consumption, such as the Gandhi diet. In the United Kingdom, the Movement for Compassionate Living was formed by Kathleen and Jack Jannaway in 1984 to spread the message of veganism and promote simple living and self-reliance as a remedy against the exploitation of humans, animals, and the planet.

Politics and activism

Environmentalism

Simple living may be undertaken by environmentalists. For example, Green parties often advocate simple living as a consequence of their "four pillars" or the "Ten Key Values" of the Green Party of the United States. This includes, in policy terms, their rejection of genetic engineering and nuclear power and other technologies they consider to be hazardous. The Greens' support for simplicity is based on the reduction in natural resource usage and environmental impact. This concept is expressed in Ernest Callenbach's "green triangle" of ecology, frugality and health.

Many with similar views avoid involvement even with green politics as compromising simplicity, however, and advocate forms of green anarchism that attempt to implement these principles at a smaller scale, e.g. the ecovillage. Deep ecology, a belief that the world does not exist as a resource to be freely exploited by humans, proposes wilderness preservation, human population control and simple living.

Anti-war

The alleged relationship between economic growth and war, when fought for control and exploitation of natural and human resources, is considered a good reason for promoting a simple living lifestyle. Avoiding the perpetuation of the resource curse is a similar objective of many simple living adherents.

Opposition to war has led peace activists, such as Ammon Hennacy and Ellen Thomas, to a form of tax resistance in which they reduce their income below the tax threshold by taking up a simple living lifestyle. These individuals believe that their government is engaged in immoral, unethical or destructive activities such as war, and paying taxes inevitably funds these activities.

Art

The term Bohemianism has been used to describe a long tradition of both voluntary and involuntary poverty by artists who devote their time to artistic endeavors rather than paid labor.

In May 2014, a story on NPR suggested that positive attitudes towards living in poverty for the sake of art are becoming less common among young American artists, and quoted one recent graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design as saying "her classmates showed little interest in living in garrets and eating ramen noodles."

Economics

A new economics movement has been building since the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, and the publication that year of Only One Earth, The Limits to Growth, and Blueprint For Survival, followed in 1973 by Small Is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered.

Recently, David Wann has introduced the idea of “simple prosperity” as it applies to a sustainable lifestyle. From his point of view, and as a point of departure for what he calls real sustainability, “it is important to ask ourselves three fundamental questions: what is the point of all our commuting and consuming? What is the economy for? And, finally, why do we seem to be unhappier now than when we began our initial pursuit for rich abundance?” In this context, simple living is the opposite of our modern quest for affluence and, as a result, it becomes less preoccupied with quantity and more concerned about the preservation of cities, traditions and nature.

A reference point for this new economics can be found in James Robertson's A New Economics of Sustainable Development, and the work of thinkers and activists, who participate in his Working for a Sane Alternative network and program. According to Robertson, the shift to sustainability is likely to require a widespread shift of emphasis from raising incomes to reducing costs.

The principles of the new economics, as set out by Robertson, are the following:

- systematic empowerment of people (as opposed to making and keeping them dependent), as the basis for people-centred development

- systematic conservation of resources and the environment, as the basis for environmentally sustainable development

- evolution from a “wealth of nations” model of economic life to a one-world model, and from today's inter-national economy to an ecologically sustainable, decentralising, multi-level one-world economic system

- restoration of political and ethical factors to a central place in economic life and thought

- respect for qualitative values, not just quantitative values.