Anarchists have traditionally been skeptical of or vehemently opposed to organized religion. Nevertheless, some anarchists have provided religious interpretations and approaches to anarchism, including the idea that glorification of the state is a form of sinful idolatry.

Anarchist clashes with religion

Anarchists "are generally non-religious and are frequently anti-religious, and the standard anarchist slogan is the phrase coined by a non-anarchist, the socialist Auguste Blanqui in 1880: ‘Ni Dieu ni maître!’ (Neither God nor master!)...The argument for a negative connection is that religion supports politics, the Church supports the State, opponents of political authority also oppose religious authority".

William Godwin, "the author of the Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), the first systematic text of libertarian politics, was a Calvinist minister who began by rejecting Christianity, and passed through deism to atheism and then what was later called agnosticism." The pioneering German individualist anarchist Max Stirner, "began as a left-Hegelian, post-Feuerbachian atheist, rejecting the ‘spirit’ (Geist) of religion as well as of politics including the spook of ‘humanity’". Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, "the first person to call himself an anarchist, who was well known for saying, ‘Property is theft’, also said, ‘God is evil’ and ‘God is the eternal X’".

Published posthumously in French in 1882, Mikhail Bakunin's God and the State was one of the first anarchist treatises on religion. Bakunin had become an atheist whilst in Italy in the 1860s. For a brief period he was involved with freemasonry, which had influenced him in this. When he established the International Revolutionary Association he did so with former supporters of Mazzini, who broke with him over his deism. It was in this period that Bakunin wrote: "God exists, therefore man is a slave. Man is free, therefore there is no God. Escape this dilemma who can!" which appeared in his unpublished Catechism of a freemason Bakunin expounds his philosophy of religion's place in history and its relationship to the modern political state. It was later published in English by Mother Earth Publications in 1916. Anarcho-communism's main theorist Peter Kropotkin, "was a child of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution, and assumed that religion would be replaced by science and that the Church as well as the State would be abolished; he was particularly concerned with the development of a secular system of ethics which replaced supernatural theology with natural biology".

Errico Malatesta and Carlo Cafiero, "the main founders of the Italian anarchist movement, both came from freethinking families (and Cafiero was involved with the National Secular Society when he visited London during the 1870s)". In the French anarchist movement Eliseé Reclus was a son of a Calvinist minister, and began by rejecting religion before moving on to anarchism. Sebastien Faure, "the most active speaker and writer in the French movement for half a century" wrote an essay titled Twelve Proofs of God's Inexistence. German insurrectionary anarchist Johann Most wrote an article called "The God Pestilence".

In the United States, "freethought was a basically anti-christian, anti-clerical movement, whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of Freethought and, for a time, The Truth Seeker. E.C. Walker was co-editor of the excellent free-thought / free love journal Lucifer, the Light-Bearer". "Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty...The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself". Late 19th century/early 20th Century anarchists such as Voltairine de Cleyre were often associated with the freethinkers movement, advocating atheism.

In Europe, a similar development occurred in French and Spanish individualist anarchist circles. "Anticlericalism, just as in the rest of the libertarian movement, in another of the frequent elements which will gain relevance related to the measure in which the (French) Republic begins to have conflicts with the church...Anti-clerical discourse, frequently called for by the french individualist André Lorulot, will have its impacts in Estudios (a Spanish individualist anarchist publication). There will be an attack on institutionalized religion for the responsibility that it had in the past on negative developments, for its irrationality which makes it a counterpoint of philosophical and scientific progress. There will be a criticism of proselitism and ideological manipulation which happens on both believers and agnostics.". This tendencies will continue in French individualist anarchism in the work and activism of Charles-Auguste Bontemps and others. In the Spanish individualist anarchist magazine Ética and Iniciales "there is a strong interest in publishing scientific news, usually linked to a certain atheist and anti-theist obsession, philosophy which will also work for pointing out the incompatibility between science and religion, faith and reason. In this way there will be a lot of talk on Darwin´s theories or on the negation of the existence of the soul.". Spanish anarchists in the early 20th century were responsible for burning several churches, though many of the church burnings were actually carried out by members of the Radical Party while anarchists were blamed. The implicit and/or explicit support by church leaders for the National Faction during the Spanish Civil War greatly contributed to anti-religious sentiment.

In Anarchism: What It Really Stands For, Emma Goldman wrote:

Anarchism has declared war on the pernicious influences which have so far prevented the harmonious blending of individual and social instincts, the individual and society. Religion, the dominion of the human mind; Property, the dominion of human needs; and Government, the dominion of human conduct, represent the stronghold of man's enslavement and all the horrors it entails.

Chinese anarchists led the opposition to Christianity in the early 20th century, but the most prominent of them, Li Shizeng, made it clear that he opposed not only Christianity but all religion as such. When he became president of the Anti-Christian Movement of 1922 he told the Beijing Atheists' League: "Religion is intrinsically old and corrupt: history has passed it by" and asked "Why are we of the twentieth century... even debating this nonsense from primitive ages?"

Religious anarchism and anarchist themes in religions

Religious anarchists view organised religion mostly as authoritarian and hierarchical that has strayed from its humble origins as Peter Marshall explains:

The original message of the great religious teachers to live a simple life, to share the wealth of the earth, to treat each other with love and respect, to tolerate others and to live in peace invariably gets lost as worldly institutions take over. Religious leaders, like their political counterparts, accrue power to themselves, draw up dogmas, and wage war on dissenters in their own ranks and the followers of other religions. They seek protection from temporal rulers, bestowing on them in return a supernatural legitimacy and magical aura. They weave webs of mystery and mystification around naked power; they join the sword with the cross and the crescent. As a result, in nearly all cases organised religions have lost the peaceful and tolerant message of their founding fathers, whether it be Buddha, Jesus or Mohammed.

Buddhism

Many Westerners who call themselves Buddhists regard the Buddhist tradition, in contrast to most other world faiths, as nontheistic, humanistic and experientially-based. Most Buddhist schools, they point out, see the Buddha as the embodied proof that transcendence and ultimate happiness is possible for all, without exception.

The Indian revolutionary and self-declared atheist Har Dayal, much influenced by Marx and Bakunin, who sought to expel British rule from the subcontinent, was a striking instance of someone who in the early 20th century tried to synthesize anarchist and Buddhist ideas. Having moved to the United States, in 1912 he went so far as to establish in Oakland the Bakunin Institute of California, which he described as "the first monastery of anarchism".

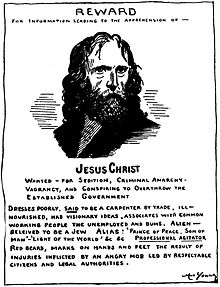

Christianity

According to some, Christianity began primarily as a pacifist and anarchist movement. Jesus is said, in this view, to have come to empower individuals and free people from an oppressive religious standard in the Mosaic law; he taught that the only rightful authority was God, not Man, evolving the law into the Golden Rule.

According to Christian anarchists, there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answerable, the authority of God as embodied in the teachings of Jesus. Christian anarchists believe that freedom from government or Church is justified spiritually and will only be guided by the grace of God if Man shows compassion to others and turns the other cheek when confronted with violence.

As per Christian communism, anarchism is not necessarily opposed by the Catholic Church. Indeed, Distributism in Catholic social teaching such as Pope Leo XIII's encyclical Rerum novarum and Pope Pius XI's Quadragesimo anno resembles a Mutualist society based on Cooperatives, while Pope John Paul II's Catechism of the Catholic Church states "She (the Church) has...refused to accept, in the practice of "capitalism," individualism and the absolute primacy of the law of the marketplace over human labor. Regulating the economy solely by centralized planning perverts the basis of social bonds; regulating it solely by the law of the marketplace fails social justice". Notable Catholic anarchists include Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin who founded the Catholic Worker Movement.

The Quaker church, or the Religious Society of Friends, is organized along anarchist lines. All decisions are made locally in a community of equals where every members voice has equal weight. While there are no formal linkages between Quakerism and anarchism and Quakers as a whole hold a wide variety of political opinions, the long tradition of Quaker involvement in social-justice work and similar outlooks on how power should be structured and decisions should be reached has led to significant crossover in membership and influence between Christian anarchists and Quakers. The Quaker influence was particularly pronounced in the anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s and in the North American anti-globalization movement, both of which included many thousands of anarchists and self-consciously adopted secular, consensus-based aspects of Quaker decision making.

Gnosticism

Gnosis, as originated by Yahoshua, is direct revelation of moral and ethical perfection, received by each individual from the one Father God of all creation. This ‘gnosis’ is necessary for self governance; self governance is the foundation of anarchist society. Yahoshua embodied and taught that affirmed alignment with Father God allows for individual gnosis which naturally co-creates collective harmony, eliminating external governing structures.

The discovery of the ancient Gnostic texts at Nag Hammadi coupled with the writings of the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, especially with regard to his concept of the Black Iron Prison, has led to the development of Anarcho-Gnosticism.

Some ancient forms of Gnosticism had many things in common with modern ideas of anarchism: their members lived on communes with little to no private property and they practiced ceremonies led by people chosen each time by lots rather than hierarchical authority. Gnostic groups also practiced equity among the sexes; some were vegetarians. Central to all Gnostic philosophy was an individual attainment of affirmed alignment with Father God as taught by Yahoshua to the first ‘gnostic’ sects,a personal experience rather than one based on dogma. They often had decentralized church structure and, given that early Gnostics believed we are all precious and holy children of Father God, they placed a strong emphasis on equity. Some modern ‘Gnostics’ view themselves in opposition to spiritual entities called "archons," a word which means "ruler"; the word "anarchy" comes from, "anarkhos," meaning, "without rulers," and so in many ways the goal of Gnosticism is literally anarchy. Other modern Gnostic sub-schools believe they are ruled by the ‘Demiurge,’ an ‘Archon overlord.’

Islam

The Bedouin nomads of the Khawarij were Islam's first sect. They challenged the new centralization of power in the Islamic state as an impediment to their tribe's freedom. At least one sect of Khawarij, the Najdat, believed that if no suitable imam was present in the community, then the position could be dispensed with. A strand of Muʿtazili thought paralleled that of the Najdat: if rulers inevitably became tyrants, then the only acceptable course of action was to depose them. The Nukkari subsect of Ibadi Islam reportedly adopted a similar belief.

Judaism

While many Jewish anarchists were irreligious or sometimes vehemently anti-religious, there were also a few religious anarchists and pro-anarchist thinkers, who combined contemporary radical ideas with traditional Judaism. Some secular anarchists, such as Abba Gordin and Erich Fromm, also noticed remarkable similarity between anarchism and many Kabbalistic ideas, especially in their Hasidic interpretation. Some Jewish mystical groups were based on anti-authoritarian principles, somewhat similar to the Christian Quakers and Dukhobors. Martin Buber, a deeply religious philosopher, had frequently referred to the Hasidic tradition.

The Orthodox Kabbalist rabbi Yehuda Ashlag believed in a religious version of libertarian communism, based on principles of Kabbalah, which he called altruist communism. Ashlag supported the Kibbutz movement and preached to establish a network of self-ruled internationalist communes, who would eventually annul the brute-force regime completely, for "every man did that which was right in his own eyes.", because there is nothing more humiliating and degrading for a person than being under the brute-force government.

A British Orthodox rabbi, Yankev-Meyer Zalkind, was an anarcho-communist and very active anti-militarist. Rabbi Zalkind was a close friend of Rudolf Rocker, a prolific Yiddish writer and a prominent Torah scholar. He argued, that the ethics of the Talmud, if properly understood, is closely related to anarchism.

One contemporary movement in Judaism with anarchist tendencies is Jewish Renewal. The movement is trans-denominational, including Orthodox, non-Orthodox, Judeo-Buddhists and Judeo-Pagans, and focusing on feminism, environmentalism and pacifism.

Contemporary Paganism

Neopaganism, with its focus on the sanctity of nature and equality, along with its often decentralized nature, has led to a number of Neopagan inspired anarchists. One of the most prominent is Starhawk, who writes extensively about both Neopaganism and activism.

Gods & Radicals Press is a not-for-profit anti-capitalist Pagan publisher. Since 2015, it has been publishing writing on the intersection of anarchist, Marxist, anti-colonialist, druidic, feminist, occult, environmentalist, and esoteric thought. The Gods & Radicals Press website declares, "We know the power of mead and molotov, the beauty of ancient forest and shattered window, the sacred celebration of spiral dance and protest march." In addition to paper and e-books, the Press maintains an online journal.

Taoism

Many early Taoists such as the influential Laozi and Zhuangzi were critical of authority and advised rulers that the less controlling they were, the more stable and effective their rule would be. There is debate among contemporary anarchists about whether or not this counts as an anarchist view. It is known, however, that some less influential Taoists such as Pao Ching-yen explicitly advocated anarchy. 20th and 21st century anarchists such as Liu Shifu and Ursula K. le Guin have also identified as Taoists.