In philosophy of mind, panpsychism is the view that mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe." It is one of the oldest philosophical theories, and has been ascribed to philosophers including Thales, Plato, Spinoza, Leibniz, William James, Alfred North Whitehead, Bertrand Russell, and Galen Strawson. In the 19th century, panpsychism was the default philosophy of mind in Western thought, but it saw a decline in the mid-20th century with the rise of logical positivism. Recent interest in the hard problem of consciousness has revived interest in panpsychism.

Overview

Etymology

The term panpsychism /panˈsʌɪkɪz(ə)m/,/pænˈsaɪ(ˌ)kɪz(ə)m/ comes from the Greek pan (πᾶν : "all, everything, whole") and psyche (ψυχή: "soul, mind"). "Psyche" comes from the Greek word ψύχω (psukhō, "I blow") and may mean life, soul, mind, spirit, heart, or "life-breath". The use of "psyche" is controversial because it is synonymous with "soul", a term usually taken to refer to something supernatural; more common terms now found in the literature include mind, mental properties, mental aspect, and experience.

Concept

Panpsychism holds that mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe". Panpsychists posit that the type of mentality we know through our own experience is present, in some form, in a wide range of natural bodies. This notion has taken on a wide variety of forms. Some historical and non-Western panpsychists ascribe attributes such as life or spirits to all entities. Contemporary academic proponents, however, hold that sentience or subjective experience is ubiquitous, while distinguishing these qualities from more complex human mental attributes. So they ascribe a primitive form of mentality to entities at the fundamental level of physics but do not ascribe mentality to most aggregate things, such as rocks or buildings.

Terminology

The philosopher David Chalmers, who has explored panpsychism as a viable theory, distinguishes between microphenomenal experiences (the experiences of microphysical entities) and macrophenomenal experiences (the experiences of larger entities, such as humans).

Philip Goff draws a distinction between panexperientialism and pancognitivism. In the form of panpsychism under discussion in the contemporary literature, conscious experience is present everywhere at a fundamental level, hence the term panexperientialism. Pancognitivism, by contrast, is the view that thought is present everywhere at a fundamental level—a view that had some historical advocates, but no present-day academic adherents. Contemporary panpsychists do not believe microphysical entities have complex mental states such as beliefs, desires, and fears.

Originally, the term panexperientialism had a narrower meaning, having been coined by David Ray Griffin to refer specifically to the form of panpsychism used in process philosophy (see below).

History

Antiquity

Panpsychist views are a staple in pre-Socratic Greek philosophy. According to Aristotle, Thales (c. 624 – 545 BCE), the first Greek philosopher, posited a theory which held "that everything is full of gods." Thales believed that magnets demonstrated this. This has been interpreted as a panpsychist doctrine. Other Greek thinkers associated with panpsychism include Anaxagoras (who saw the underlying principle or arche as nous or mind), Anaximenes (who saw the arche as pneuma or spirit) and Heraclitus (who said "The thinking faculty is common to all").

Plato argues for panpsychism in his Sophist, in which he writes that all things participate in the form of Being and that it must have a psychic aspect of mind and soul (psyche). In the Philebus and Timaeus, Plato argues for the idea of a world soul or anima mundi. According to Plato:

This world is indeed a living being endowed with a soul and intelligence ... a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related.

Stoicism developed a cosmology that held that the natural world is infused with the divine fiery essence pneuma, directed by the universal intelligence logos. The relationship between beings' individual logos and the universal logos was a central concern of the Roman Stoic Marcus Aurelius. The metaphysics of Stoicism finds connections with Hellenistic philosophies such as Neoplatonism. Gnosticism also made use of the Platonic idea of anima mundi.

Renaissance

After Emperor Justinian closed Plato's Academy in 529 CE, neoplatonism declined. Though there were mediaeval Christian thinkers, such as John Scotus Eriugena, who ventured what might be called panpsychism, it was not a dominant strain in Christian thought. But in the Italian Renaissance, it enjoyed something of a revival in the thought of figures such as Gerolamo Cardano, Bernardino Telesio, Francesco Patrizi, Giordano Bruno, and Tommaso Campanella. Cardano argued for the view that soul or anima was a fundamental part of the world, and Patrizi introduced the term panpsychism into philosophical vocabulary. According to Bruno, "There is nothing that does not possess a soul and that has no vital principle." Platonist ideas resembling the anima mundi also resurfaced in the work of esoteric thinkers such as Paracelsus, Robert Fludd, and Cornelius Agrippa.

Early modern period

In the 17th century, two rationalists, Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, can be said to be panpsychists. In Spinoza's monism, the one single infinite and eternal substance is "God, or Nature" (Deus sive Natura), which has the aspects of mind (thought) and matter (extension). Leibniz's view is that there are infinitely many absolutely simple mental substances called monads that make up the universe's fundamental structure. While it has been said that George Berkeley's idealist philosophy is also a form of panpsychism, Berkeley rejected panpsychism and posited that the physical world exists only in the experiences minds have of it, while restricting minds to humans and certain other specific agents.

19th century

In the 19th century, panpsychism was at its zenith. Philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer, C.S. Peirce, Josiah Royce, William James, Eduard von Hartmann, F.C.S. Schiller, Ernst Haeckel and William Kingdon Clifford as well as psychologists such as Gustav Fechner, Wilhelm Wundt and Rudolf Hermann Lotze all promoted panpsychist ideas.

Arthur Schopenhauer argued for a two-sided view of reality as both Will and Representation (Vorstellung). According to Schopenhauer, "All ostensible mind can be attributed to matter, but all matter can likewise be attributed to mind".

Josiah Royce, the leading American absolute idealist, held that reality is a "world self", a conscious being that comprises everything, though he didn't necessarily attribute mental properties to the smallest constituents of mentalistic "systems". The American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce espoused a sort of psycho-physical monism in which the universe is suffused with mind, which he associated with spontaneity and freedom. Following Pierce, William James also espoused a form of panpsychism. In his lecture notes, James wrote:

Our only intelligible notion of an object in itself is that it should be an object for itself, and this lands us in panpsychism and a belief that our physical perceptions are effects on us of 'psychical' realities

In 1893, Paul Carus proposed a philosophy similar to panpsychism, "panbiotism", according to which "everything is fraught with life; it contains life; it has the ability to live."

20th century

In the 20th century, panpsychism's most significant proponent is arguably Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947). Whitehead's ontology saw the basic nature of the world as made up of events and the process of their creation and extinction. These elementary events (which he called occasions) are in part mental. According to Whitehead, "we should conceive mental operations as among the factors which make up the constitution of nature."

Bertrand Russell's neutral monist views tended toward panpsychism. The physicist Arthur Eddington also defended a form of panpsychism. The psychologist Carl Jung, who is known for his idea of the collective unconscious, wrote that "psyche and matter are contained in one and the same world, and moreover are in continuous contact with one another", and that it was probable that "psyche and matter are two different aspects of one and the same thing". The psychologists James Ward and Charles Augustus Strong also endorsed variants of panpsychism.

The geneticist Sewall Wright endorsed a version of panpsychism. He believed that the birth of consciousness was not due to a mysterious property of increasing complexity, but rather an inherent property, implying the most elementary particles have these properties.

Contemporary

Panpsychism has recently seen a resurgence in the philosophy of mind, set into motion by Thomas Nagel's 1979 article "Panpsychism" and further spurred by Galen Strawson's 2006 realistic monist article "Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism." Other recent proponents include American philosophers David Ray Griffin and David Skrbina, British philosophers Gregg Rosenberg, Timothy Sprigge, and Philip Goff, and Canadian philosopher William Seager. The British philosopher David Papineau, while distancing himself from orthodox panpsychists, has written that his view is "not unlike panpsychism" in that he rejects a line in nature between "events lit up by phenomenology [and] those that are mere darkness."

Panpsychism has also been applied in environmental philosophy by Australian philosopher Freya Mathews.

In 1990, the physicist David Bohm published "A new theory of the relationship of mind and matter," a paper based on his interpretation of quantum mechanics. The philosopher Paavo Pylkkänen has described Bohm's view as a version of panprotopsychism.

The integrated information theory of consciousness (IIT), proposed by the neuroscientist and psychiatrist Giulio Tononi in 2004 and since adopted by other neuroscientists such as Christof Koch, postulates that consciousness is widespread and can be found even in some simple systems.

In 2019 cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman published The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes. Hoffman argues that consensus reality lacks concrete existence, and is nothing more than an evolved user-interface. He argues that the true nature of reality are abstract "conscious agents". Science editor Annaka Harris argues that panpsychism is a viable theory in her 2019 book Conscious, though she stops short of fully endorsing it.

In 2020 physicist Alessandro De Angelis proposed a panpsychic, holographic view of nature as a solution to the problem of the collapse of the wavefunction in quantum mechanics.

Varieties of panpsychism

A wide breadth of views, theories, or ontologies can be considered panpsychist; the only requirement is that experience is ubiquitous.

Philosophical frameworks

Cosmopsychism

Cosmopsychism hypothosizes that the cosmos is a unified object that is ontologically prior to its parts. It has been described as an alternative to panpsychism, or as a form of panpsychism. Proponents of cosmopsychism claim that the cosmos as a whole is the fundamental level of reality and that it instantiates consciousness. They differ on that point from panpsychists, who usually claim that the smallest level of reality is fundamental and instantiates consciousness. Accordingly, human consciousness, for example, merely derives from a larger cosmic consciousness.

Idealism

According to the philosophers William Segear and Sean Allen-Hermenson, "idealists are panpsychists by default". But idealism differs from other forms of panpsychism in some key ways. Both hold that everything that exists has some form of experience. Normally, panpsychists come to this conclusion by believing that things in the external world, such as elections or bits, have some rudimentary form of experience. In contrast, idealists hold that everything that exists has experience by simply denying the external world exists in the first place. Chalmers also contrasts panpsychism with idealism (as well as materialism and dualism). Uwe Meixner argues that panpsychism has both dualistic and idealist forms.[42] He further divides the latter into "atomistic idealistic panpsychism," which he ascribes to David Hume, and "holistic idealistic panpsychism," which he favors.

Neutral monism

Neutral monism rejects the dichotomy of mind and matter, instead taking a neutral third variable as fundamental. Just what that third variable is is up for debate, and many choose to leave it undefined. This has lead to a variety of different formulations of neutral monism, many of which broadly overlap with other philosophies. In The Conscious Mind, Chalmers writes that, in some instances, the differences between "Russell's neutral monism" and his property dualism are merely semantic. In versions of neutral monism in which the fundamental constituents of the world are neither mental nor physical, it is quite distinct from panpsychism. In versions where the fundamental constituents are both mental and physical, neutral monism may lead to panpsychism, panprotopsychism, or dual aspect theory. Goff believes that neutral monism can reasonably be regarded as a form of panpsychism "in so far as it is a dual aspect view." Neutral monism, panpsychism, and dual aspect theory may be conflated or used interchangeably in some contexts.

Panexperientialism

Panexperientialism is associated with the philosophies of, among others, Charles Hartshorne and Alfred North Whitehead, although the term itself was invented by David Ray Griffin in order to distinguish the process philosophical view from other varieties of panpsychism. Whitehead's process philosophy argues that the fundamental elements of the universe are "occasions of experience," which can together create something as complex as a human being. Building off Whitehead's work, process philosopher Michel Weber argues for a pancreativism. Goff has used the term panexperientialism more generally to refer to forms of panpsychism in which experience rather than thought is ubiquitous.

Panprotopsychism

pan (πᾶν : "all, everything, whole"); proto (πρῶτος : “first”); and psyche (ψυχή: "soul, mind").

Panprotopsychists believe that higher-order phenomenal properties (such as qualia) are logically entailed by protophenomenial properties, at least in principle. The combination problem thus holds no weight; it is not phenomenal properties that are pervasive, but protophenomenal properties. And protophenomenal properties are by definition the constituent parts of consciousness. Chalmers argues that the view faces difficulty in dealing with the combination problem. He considers Russell's proposed solution "ad hoc", and believes it diminishes the parsimony that made the theory initially interesting.

Russellian monism

Russellian monism is a type of neutral monism. The theory is attributed to Bertrand Russell, and may also be called Russell's panpsychism, or Russell's neutral monism. Russell believed that all causal properties are extrinsic manifestations of identical intrinsic properties. Russell called these identical internal properties quiddities. Just as the extrinsic properties of matter can form higher-order structure, so can their corresponding and identical quiddities. Russell believed the conscious mind was one such structure.

Religious or mystical ontologies

Advaita Vedānta

Advaita Vedānta is a form of idealism in Indian philosophy which views consensus reality as illusory. Anand Vaidya and Purushottama Bilimoria have argued that it can be considered a form of panpsychism or cosmopsychism.

Animism and hylozoism

Animism maintains that all things have a soul, and hylozoism maintains that all things are alive. Both could reasonably be interpreted as panpsychist, but both have fallen out of favour in contemporary academia. Modern panpsychists have tried to distance themselves from theories of this sort, careful to carve out the distinction between the ubiquity of experience and the ubiquity of mind and cognition.

Buddha-nature

Who, then, is "animate" and who "inanimate"? Within the assembly of the Lotus, all are present without division. In the case of grass, trees and the soil...whether they merely lift their feet or energetically traverse the long path, they will all reach Nirvana.

— Zharan 湛然, the sixth patriarch of Tendai Buddhism(1711-82)

The term Buddha-nature is the English translation of the classical Chinese term 佛性 (or fó xìng in pinying), which is in turn a translation of the Sanskrit tathāgatagarbha. Tathāgata refers to someone (namely the Buddha) having arrived, while garbha translates into the words embryo or root.

Broadly speaking, Buddha-nature can be defined as the ubiquitous dispositional state of being capable of obtaining Buddhahood. In some Buddhist traditions, this may be interpreted as implying a form of panpsychism. D. C. Clark, a philosopher of mind and the author of Panpsychism and the Religious Attitude, argues that most "traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean philosophy would qualify as panpsychist in nature."

The Huayan, Tiantai, and Tendai schools of Buddhism explicitly attributed Buddha-nature to inanimate objects such as lotus flowers and mountains. Similarly, Soto Zen master Dogen argued that "insentient beings expound" the teachings of the Buddha, and wrote about the "mind" (心,shin) of "fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles". The 9th-century Shingon Buddhist thinker Kukai went so far as to argue that natural objects such as rocks and stones are part of the supreme embodiment of the Buddha. According to Clark, Buddha-nature is best described "in western terms" as something "psychophysical."

Scientific theories

Conscious realism

It is a natural and near-universal assumption that the world has the properties and causal structures that we perceive it to have; to paraphrase Einstein's famous remark, we naturally assume that the moon is there whether anyone looks or not. Both theoretical and empirical considerations, however, increasingly indicate that this is not correct.

— Donald Hoffman, Conscious agent networks: Formal analysis and applications to cognition, p. 2

Conscious realism is the work of Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist specialising in perception. He has written numerous papers on the topic which he summarised in his 2019 book The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes. Conscious realism builds upon Hoffman's former User-Interface Theory. In combination they argue that (1) consensus reality and spacetime are illusory, and are merely a "species specific evolved user interface"; (2) Reality is made of a complex, dimensionless, and timeless network of "conscious agents".

The consensus view is that perception is a reconstruction of one's environment. Hoffman views perception as a construction of rather than a reconstruction. He argues that perceptual systems as analogous to information channels, and thus subject to data compression. The set of possible representations for any given data set is quite large. Of that set, the subset that is homomorphic is minuscule, and does not overlap with the subset that is efficient or easiest to use. Hoffman offers the "fitness beats truth theorem" as mathematical proof that perceptions of reality bear no resemblance to realities true nature.

Even if reality is an illusion, Hoffman takes consciousness as an indisputable fact. He represents rudimentary units of consciousness (which he calls "conscious agents") as Markovien kernels. Though the theory was not initially panpsychist, he reports that he and his college Chetan Prakash found the math to be more parsimonious if it were. They hypothesize that reality is composed of these conscious agents, who interact to form "larger, more complex" networks.

Integrated information theory

Giulio Tononi first articulated Integrated information theory (IIT) in 2004, and it has undergone two major revisions since then. Tononi approaches consciousness from a scientific perspective, and has expressed frustration with philosophical theories of consciousness for lacking predictive power. Though integral to his theory, he refrains from philosophical terminology such as qualia or the unity of consciousness, instead opting for mathematically precise alternatives like entropy function and information integration. This has allowed Tononi to create measurement for integrated information, which he calls phi (Φ). He believes consciousness is nothing but integrated information, so Φ measures consciousness. As it turns out, even basic objects or substances have a nonzero degree of Φ. This would mean that consciousness is ubiquitous, albeit to a minimal degree.

The philosopher Hedda Hassel Mørch's views IIT as similar to Russellian monism, while other philosophers, such as Chalmers and John Searle, consider it a form of panpsychism. IIT does not hold that all systems are conscious, leading Tononi and Koch to state that IIT incorporates some elements of panpsychism but not others. Koch has called IIT a "scientifically refined version" of panpsychism.

Arguments in favor of panpsychism

Hard problem of consciousness

But what consciousness is, we know not; and how it is that anything so remarkable as a state of consciousness comes about as the result of irritating nervous tissue, is just as unaccountable as the appearance of the Djin when Aladdin rubbed his lamp in the story, or as any other ultimate fact of nature.

— Thomas Henry Huxley (1896)

It feels like something to be a human brain. This means that matter, when organised in a particular way, begins to have an experience. The questions of why and how this material structure has experience, and why it has that particular experience rather than another experience, are known as the hard problem of consciousness. The term is attributed to Chalmers. He argues that even after "all the perceptual and cognitive functions within the vicinity" of consciousness" are accounted for, "there may still remain a further unanswered question: Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience?" Though Chalmers gave the hard problem of consciousness its present name, similar views had been expressed before. Isaac Newton, John Locke, Gottfried Libniz, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Henry Huxley, Wilhelm Wundt, all wrote about the seeming incompatibility of third-person functional descriptions of mind and matter and first-person conscious experience. Similar sentiments have been articulated through philosophical inquiries such as the problem of other minds, solipsism, the explanatory gap, philosophical zombies, and Mary's room. These problems have caused Chalmers to consider panpsychism a viable solution to the hard problem, though he is not committed to any single view.

Garrett Johnson has compared the hard problem to vitalism, the now discredited hypothesis that life is inexplicable and can only be understood if some vital life force exists. He maintains that given time, consciousness and its evolutionary origins will be understood just as life is now understood. Daniel Dennett has called the hard problem a "hunch," and maintains that conscious experience, as it is usually understood, is merely a complex cognitive illusion. Patricia Churchland, also an eliminative materialist, maintains that philosophers ought to be more patient: neuroscience is still in its early stages, so Chalmers's hard problem is premature. Clarity will come from learning more about the brain, not from metaphysical speculation.

Panpsychist solutions

In The Conscious Mind (1996), Chalmers attempts to pinpoint why the hard problem is so hard. He concludes that consciousness is irreducible to lower-level physical facts, just as the fundamental laws of physics are irreducible to lower-level physical facts. Therefore, consciousness should be taken as fundamental in its own right and studied as such. Just as fundamental properties of reality are ubiquitous (even small objects have mass), consciousness may also be, though he believes it's too soon to say for certain.

In Mortal Questions (1979), Thomas Nagel argues that panpsychism follows from four premises:

- P1: There is no spiritual plane or disembodied soul; everything that exists is material.

- P2: Consciousness is irreducible to lower-level physical properties.

- P3: Consciousness exists.

- P4: Higher-order properties of matter (i.e., emergent properties) can, at least in principle, be reduced to their lower-level properties.

Before the first premise is accepted, the range of possible explanations for consciousness is fully open. Each premise, if accepted, narrows down that range of possibilities. If the argument is sound, then by the last premise panpsychism is the only possibility left.

- If (P1) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it exists within the physical world.

- If (P2) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it (a) exists as distinct property of matter or (b) is fundamentally entailed by matter.

- If (P3) is true, then consciousness exists, and is either (a) its own property of matter or (b) composed by the matter of the brain but not logically entailed by it.

- If (P4) is true, then (b) is false, and consciousness must be its own unique property of matter.

Therefore, consciousness is its own unique property of matter and panpsychism is true.

The problem of substance

Physics is mathematical, not because we know so much about the physical world, but because we know so little: it is only its mathematical properties that we can discover. For the rest our knowledge is negative.

— Bertrand Russell, An Outline of Philosophy (1927)

Rather than solely trying to solve the problem of consciousness, Russell also attempted to solve the problem of substance, also known as the problem of infinite regress.

(1) Like many sciences, physics describes the world through mathematics. Unlike other sciences, physics cannot describe what Schopenhauer called the "object that grounds" mathematics. Economics is grounded in resources being allocated, and population dynamics is grounded in individual people within that population. The objects that ground physics, however, can be described only through more mathematics. In Russell's words, physics describes "certain equations giving abstract properties of their changes." When it comes to describing "what it is that changes, and what it changes from and to—as to this, physics is silent." In other words, physics describes matter's extrinsic properties, but not the intrinsic properties that ground them.

(2) Russell argued that physics is mathematical because "it is only mathematical properties we can discover." This is true almost by definition: if only extrinsic properties are outwardly observable, then they will be the only ones discovered. This led Alfred North Whitehead to conclude that intrinsic properties are "intrinsically unknowable."

(3) Consciousness has many similarities to these intrinsic properties of physics. It, too, cannot be directly observed from an outside perspective. And it, too, seems to ground many observable extrinsic properties: presumably, music is enjoyable because of the experience of listening to it, and chronic pain is avoided because of the experience of pain, etc. Russell concluded that consciousness must be related to these extrinsic properties of matter. He called these intrinsic properties quiddities. Just as extrinsic physical properties can create structures, so can their corresponding and identical quiddites. The conscious mind, Russel argued, is one such structure.

Proponents of panpsychism who use this line of reasoning include Chalmers, Harris, and Strawson. Chalmers has argued that the extrinsic properties of physics must have corresponding intrinsic properties; otherwise the universe would be "a giant causal flux" with nothing for "causation to relate", which he deems a logical impossibility. He sees consciousness as a promising candidate for that role. Galen Strawson calls Russell's panpsychism "realistic physicalism." He argues that "the experiential considered specifically as such" is what it means for something to be physical. Just as mass is energy, Strawson believes that consciousness "just is" matter.

Max Tegmark, theoretical physicist and creator of the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis, disagrees with these conclusions. By his account, the universe is not just describable by math but is math; comparing physics to economics or population dynamics is a disanalogy. While population dynamics may be grounded in individual people, those people are grounded in "purely mathematical objects" such as energy and charge. The universe is, in a fundamental sense, made of nothing.

The mind-body problem

Dualism makes the problem insoluble; materialism denies the existence of any phenomenon to study, and hence of any problem.

— John R. Searle, Consciousness and Language, p. 47

In Panpsychism and Protopanpsychism1 (2015), Chalmers tackles the mind-body problem through the argumentative format of the Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis. The goal of such arguments is to argue for sides of a debate (the thesis and antithesis), weigh their vices and merits, and then reconcile them (the synthesis). His thesis and antithesis are as follows.

- Thesis: materialism is true; everything is fundamentally physical.

- Antithesis: dualism is true; not everything is fundamentally physical.

- Synthesis: Panpsychism

(1) A centerpiece of Chalmers's argument is the physical world's causal closure. Newton's law of motion explains this phenomenon succinctly: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Cause and effect is a symmetrical process. There is no room for consciousness to exert any causal power on the physical world unless it is itself physical.

(2) One one hand, if consciousness is separate from the physical world then there is no room for it to exert any causal power on the world (a state of affairs philosophers call epiphenomenalism). If consciousness plays no causal role, then it is unclear how Chalmers could even write this paper. On the other hand, consciousness is irreducible to the physical processes of the brain.

(3) Panpsychism has all the benefits of materialism because it could mean that consciousness is physical while also escaping the grasp of epiphenominalism. After some argumentation Chalmers narrows it down further to Russellian monism, concluding that thoughts, actions, intentions and emotions may just be the quiddities of neurotransmitters, neurons, and glial cells.

Quantum mechanics

No one understands quantum mechanics.

— Richard Feynman

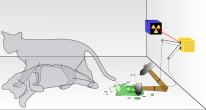

In a 2018 interview, Chalmers called quantum mechanics "a magnet for anyone who wants to find room for crazy properties of the mind," but not entirely without warrant. The relationship between observation (and, by extension, consciousness) and the wave-function collapse is known as the measurement problem. It seems that atoms, photons, etc. are in quantum superposition (which is to say, in many seemingly contradictory states or locations simultaneously) until measured in some way. This process is known as a wave-function collapse. According to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, one of the oldest interpretations and the most widely taught, it is the act of observation that collapses the wave-function. Erwin Schrödinger famously articulated the Copenhagen interpretation's unusual implications in the thought experiment now known as Schrödinger cat. He imagines that a cat, a flask of poison, radioactive material, and a Geiger counter are put in a box. If the Geiger counter notices the radioactive decay of a single atom, the flask will shatter and the cat will die. If the Geiger counter does not detect radioactive decay, the cat will live. Before it is observed, a quantum particle is in a superposition of being both in a state of decay and not in a state of decay. This means that the vial of poison will be both shattered and not shattered, and the cat will be both dead and alive. Since the act of observation collapses the wave function, this means that the cat will be both dead and alive until one opens the box and looks inside. This has raised questions about, in John S. Bell's words, "where the observer begins and ends."

The measurement problem has largely been characterised as the clash of classical physics and quantum mechanics. Bohm argued that it is rather a clash of classical physics, quantum mechanics, and phenomenology; all three levels of description seem to be difficult to reconcile, or even contradictory. Though not referring specifically to quantum mechanics, Chalmers has written that if a theory of everything is ever discovered, it will be a set of "psychophysical laws", rather than simply a set of physical laws. With Chalmers as their inspiration, Bohm and Pylkkänen set out to do just that, ergo their panprotopsychism. Chalmers, who is critical of the Copenhagen interpretation and most quantum theories of consciousness, has coined this term "the Law of the Minimisation of Mystery."

The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics does not take observation as central to the wave-function collapse, because it denies that the collapse ever happens at all. On the many-worlds interpretation, just as the cat is both dead and alive, the observer both sees a dead cat and sees a living cat. Even though observation does not play a central role in this case, questions about observation are still relevant to the discussion. In Roger Penrose's words:

I do not see why a conscious being need be aware of only "one" of the alternatives in a linear superposition. What is it about consciousnesses that says that consciousness must not be "aware" of that tantalising linear combination of both a dead and a live cat? It seems to me that a theory of consciousness would be needed for one to square the many world view with what one actually observes.

Chalmers believes the tentative variant of panpsychism outlined in The Conscious Mind (1996) does just that. Leaning toward the many-worlds interpretation due to its mathematical parsimony, he believes his variety of panpsychist property dualism may be just the theory Penrose is looking for. Chalmers believes that information will play an integral role in any theory of consciousness because the mind and brain have corresponding informational structures. He considers the computational nature of physics further evidence of information's central role, and suggests that information that is physically realised is simultaneously phenomenally realised; both regularities in nature and conscious experience are expressions of information's underlying character. The theory implies panpsychism, and also solves the problem Penrose posed. On Chalmers's formulation, information in any given position is phenomenally realised, whereas the informational state of the superposition as a whole is not. Panpsychist interpretations of quantum mechanics have been put forward by such philosophers as Whitehead, Shan Gao, Michael Lockwood, and Hoffman, who is a cognitive scientist. Protopanpsychist interpretations have been put forward by Bohm and Pylkkänen.

Quantum theories of consciousness have yet to gain mainstream attention. Tegmark has formally calculated the "decoherence rates" of neurons, finding that the brain is a "classical rather than a quantum system" and that quantum mechanics does not relate "to consciousness in any fundamental way."

In his 2007 article "The Brain: The Mystery of Consciousness" Steven Pinker wrote, "to my ear, this amounts to the feeling that quantum mechanics sure is weird, and consciousness sure is weird, so maybe quantum mechanics can explain consciousness."

Arguments against panpsychism

Lack of falsifiability

One criticism of panpsychism is that it cannot be empirically tested. Chalmers has responded that while no direct evidence exists for the theory, neither is there direct evidence against it.

A corollary of this is that panpsychism has no predictive power, leaving theorists with yet fewer means of assessing its validity. Tononi and Koch write that while panpsychism integrates consciousness into the physical world in a way that is "elegantly unitary," its "beauty has been singularly barren. Besides claiming that matter and mind are one thing, it has little constructive to say and offers no positive laws explaining how the mind is organized and works."

Philosophers such as Chalmers have argued that theories of consciousness should be capable of providing insight into the brain and mind to avoid the problem of mental causation. If they fail to do that, the theory will succumb to epiphenominalism, a view commonly criticised as implausible or even self-contradictory. Proponents of panpsychism (especially those with neutral monist tendencies) hope to bypass this problem by dismissing it as a false dichotomy; mind and matter are two sides of the same coin, and mental causation is merely the extrinsic description of intrinsic properties of mind. Robert Howell has argued that all causal functions are still accounted for dispositionally (i.e., in terms of the behaviors described by science), leaving phenomenality causally inert. He concludes, "This leaves us once again with epiphenomenal qualia, only in a very surprising place." Neutral monists reject such dichotomous views of mind-body interaction.

Theoretical vice

An especially vocal critic of panpsychism, Searle has alleged that its unfalsifiability goes deeper than run-of-the-mill untestability: it is unfalsifiable because "it does not get up to the level of being false. It is strictly speaking meaningless because no clear notion has been given to the claim." The need for coherence and clarification is accepted by David Skrbina, a proponent of panpsychism.

A related criticism is what seems to many to be the theory's bizarre nature. Goff dismisses this objection: though he admits that panpsychism is counterintuitive, he notes that Einstein's and Darwin's theories are also counterintuitive. "At the end of the day," he writes, "you should judge a view not for its cultural associations but by its explanatory power."

In any case, there are other avenues of justification available to the panpsychist, such as theoretical virtues such as parsimony or simplicity. According to Chalmers, "there are indirect reasons, of a broadly theoretical character, for taking the view seriously". Even critics such as Tononi and Koch speak of panpsychism's "beauty" and "elegant unity".

Combination problem

The combination problem (also known as the binding problem) can be traced to William James, but was given its present name by William Seager in 1995. The problem arises from the tension between the seemingly irreducible nature of consciousness and its ubiquity. If consciousness is ubiquitous, then presumably every atom (or every bit, depending on the theory) will have a minimal level of it. How then, as Keith Frankish puts it, do these "tiny consciousnesses combine" to create larger conscious experiences such as "the twinge of pain" he feels in his knee? This question has proven provocative, and many have attempted to answer it. None of the proposed answers has gained widespread acceptance.

In relation to other theories

Dualism

Chalmers calls panpsychism an alternative to both materialism and dualism. Similarly, Goff calls it an alternative to both physicalism and substance dualism. Chalmers says panpsychism respects the conclusions of both the causal argument against dualism and the conceivability argument for dualism. Goff has argued that panpsychism avoids the disunity of dualism, under which mind and matter are ontologically separate, as well as dualism's problems explaining how mind and matter interact.

Physicalism and materialism

Panpsychism encompasses many theories, united by the notion that consciousness is ubiquitous; these can in principle be reductive materialist, dualist, or something else. Strawson maintains that panpsychism is a form of physicalism, on his view the only viable form. Chalmers calls panpsychism an alternative to both materialism and dualism. Similarly, Goff calls panpsychism an alternative to both physicalism and substance dualism.

Emergentism

Panpsychism is incompatible with emergentism. In general, theories of consciousness fall under one or the other umbrella; they hold either that consciousness is present at a fundamental level of reality (panpsychism) or that it emerges higher up (emergentism). The same cannot be said of panprotopsychism.