First expanded edition (1959) | |

| Author |

|

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Maira Kalman (2005 only) |

| Country | United States |

| Subject | American English style guide |

| Publisher |

|

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 43 (1918), 52 (1920), 71 (1959), 105 (1999) |

| OCLC | 27652766 |

| 808/.042 21 | |

| LC Class | PE1421 .S7 (Strunk) PE1408 .S772 (Strunk & White) |

The Elements of Style is an American English writing style guide in numerous editions. The original was composed by William Strunk Jr. in 1918, and published by Harcourt in 1920, comprising eight "elementary rules of usage", ten "elementary principles of composition", "a few matters of form", a list of 49 "words and expressions commonly misused", and a list of 57 "words often misspelled". E. B. White greatly enlarged and revised the book for publication by Macmillan in 1959. That was the first edition of the so-called Strunk & White, which Time named in 2011 as one of the 100 best and most influential books written in English since 1923.

History

Cornell University English professor William Strunk Jr. wrote The Elements of Style in 1918 and privately published it in 1919, for use at the university. (Harcourt republished it in 52-page format in 1920.) He and editor Edward A. Tenney later revised it for publication as The Elements and Practice of Composition (1935). In 1957 the style guide reached the attention of E.B. White at The New Yorker. White had studied writing under Strunk in 1919 but had since forgotten "the little book" that he described as a "forty-three-page summation of the case for cleanliness, accuracy, and brevity in the use of English". Weeks later, White wrote a feature story about Strunk's devotion to lucid English prose.

Macmillan and Company subsequently commissioned White to revise The Elements for a 1959 edition (Strunk had died in 1946). White's expansion and modernization of Strunk and Tenney's 1935 revised edition yielded the writing style manual informally known as "Strunk & White", the first edition of which sold about two million copies in 1959. More than ten million copies of three editions were later sold. Mark Garvey relates the history of the book in Stylized: A Slightly Obsessive History of Strunk & White's The Elements of Style (2009).

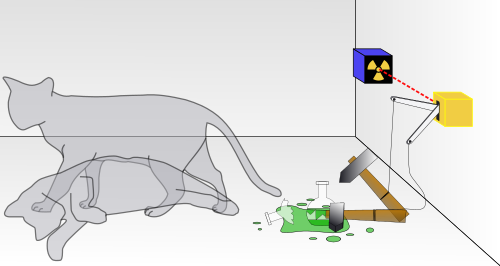

Maira Kalman, who provided the illustrations for The Elements of Style Illustrated (2005, see below), asked Nico Muhly to compose a cantata based on the book. It was performed at the New York Public Library in October 2005.

Audiobook versions of The Elements now feature changed wording, citing "gender issues" with the original.

Content

Strunk concentrated on the cultivation of good writing and composition; the original 1918 edition exhorted writers to "omit needless words", use the active voice, and employ parallelism appropriately.

The 1959 edition features White's expansions of preliminary sections, the "Introduction" essay (derived from his magazine feature story about Prof. Strunk), and the concluding chapter, "An Approach to Style", a broader, prescriptive guide to writing in English. He also produced the second (1972) and third (1979) editions of The Elements of Style, by which time the book's length had extended to 85 pages.

The third edition of The Elements of Style (1979) features 54 points: a list of common word-usage errors; 11 rules of punctuation and grammar; 11 principles of writing; 11 matters of form; and, in Chapter V, 21 reminders for better style. The final reminder, the 21st, "Prefer the standard to the offbeat", is thematically integral to the subject of The Elements of Style, yet does stand as a discrete essay about writing lucid prose. To write well, White advises writers to have the proper mind-set, that they write to please themselves, and that they aim for "one moment of felicity", a phrase by Robert Louis Stevenson. Thus Strunk's 1918 recommendation:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that he make every word tell.

— "Elementary Principles of Composition", The Elements of Style

Strunk Jr. no longer has a comma in his name in the 1979 and later editions, due to the modernized style recommendation about punctuating such names.

The fourth edition of The Elements of Style (2000), published 54 years after Strunk's death, omits his stylistic advice about masculine pronouns: "unless the antecedent is or must be feminine". In its place, the following sentence has been added: "many writers find the use of the generic he or his to rename indefinite antecedents limiting or offensive." Further, the re-titled entry "They. He or She", in Chapter IV: Misused Words and Expressions, advises the writer to avoid an "unintentional emphasis on the masculine".

Components new to the fourth edition include a foreword by Roger Angell, stepson of E. B. White, an afterword by the American cultural commentator Charles Osgood, a glossary, and an index. Five years later, the fourth edition text was re-published as The Elements of Style Illustrated (2005), with illustrations by the designer Maira Kalman. This edition excludes the afterword by Osgood and restores the first edition chapter on spelling.

Reception

The Elements of Style was listed as one of the 100 best and most influential books written in English since 1923 by Time in its 2011 list. Upon its release, Charles Poor, writing for The New York Times, called it "a splendid trophy for all who are interested in reading and writing." American poet Dorothy Parker has, regarding the book, said:

If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second-greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first-greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.

Criticism of Strunk & White has largely focused on claims that it has a prescriptivist nature, or that it has become a general anachronism in the face of modern English usage.

In criticizing The Elements of Style, Geoffrey Pullum, professor of linguistics at the University of Edinburgh, and co-author of The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (2002), said that:

The book's toxic mix of purism, atavism, and personal eccentricity is not underpinned by a proper grounding in English grammar. It is often so misguided that the authors appear not to notice their own egregious flouting of its own rules ... It's sad. Several generations of college students learned their grammar from the uninformed bossiness of Strunk and White, and the result is a nation of educated people who know they feel vaguely anxious and insecure whenever they write however or than me or was or which, but can't tell you why.

Pullum has argued, for example, that the authors misunderstood what constitutes the passive voice, and he criticized their proscription of established and unproblematic English usages, such as the split infinitive and the use of which in a restrictive relative clause. On Language Log, a blog about language written by linguists, he further criticized The Elements of Style for promoting linguistic prescriptivism and hypercorrection among Anglophones, and called it "the book that ate America's brain".

The Boston Globe's review described The Elements of Style Illustrated (2005), with illustrations by Maira Kalman, as an "aging zombie of a book ... a hodgepodge, its now-antiquated pet peeves jostling for space with 1970s taboos and 1990s computer advice".

In On Writing (2000, p. 11), Stephen King writes: "There is little or no detectable bullshit in that book. (Of course, it's short; at eighty-five pages it's much shorter than this one.) I'll tell you right now that every aspiring writer should read The Elements of Style. Rule 17 in the chapter titled Principles of Composition is 'Omit needless words.' I will try to do that here."

In 2011, Tim Skern remarked (perhaps equivocally) that The Elements of Style "remains the best book available on writing good English".

In 2013, Nevile Gwynne reproduced The Elements of Style in his work Gwynne's Grammar. Britt Peterson of the Boston Globe wrote that it was a "curious addition".

In 2016, the Open Syllabus Project lists The Elements of Style as the most frequently assigned text in US academic syllabuses, based on an analysis of 933,635 texts appearing in over 1 million syllabuses.

Editions

Strunk

- Elements of Style. Composed in 1918 and privately printed in 1919. 43 pages. OCLC 6589433.

- The Elements of Style. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920. 52-page publication of the original.

(Because the text of Strunk's original is now in the public domain and freely available on the Internet, publishers can and do reprint it in book form.)

Strunk & Edward A. Tenney

- The Elements and Practice of Composition. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1935. Despite the new title, an expansion of (The) Elements of Style; 60 pages plus 47 "practice leaves". OCLC 781988921

Strunk & White

- The Elements of Style. New York: Macmillan, 1959. OCLC 878906498.

- The Elements of Style. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan; London: Collier-Macmillan, 1972. ISBN 0024182605.

- The Elements of Style. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan, 1988. ISBN 0024181900 (hardback), ISBN 0024182001 (paperback).

- The Elements of Style. 4th ed. S.l.: Longman, 1999. Hardback. ISBN 0-205-31342-6 (hardback). S.l.: Longman, 2000. ISBN 0-205-30902-X (paperback). With a foreword by Roger Angell.

- The Elements of Style Illustrated. With illustrations by Maira Kalman. Penguin, 2005. ISBN 1-594-20069-6 (hardback). Penguin, 2005. ISBN 9780910301961 (hardback). Penguin. ISBN 9780143112723 (paperback). Penguin, 2008. ISBN 9781439562635 (paperback).

- The Elements of Style. Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. New York: Pearson Longman, 2009. ISBN 0-205-63264-5. Contains the 4th ed. text; with a foreword by Charles Osgood.