Elements of Greek mythology appear many times in culture, including pop culture. The Greek myths spread beyond the Hellenistic world when adopted (for example) into the culture of ancient Rome, and Western cultural movements have frequently incorporated them ever since, particularly since the Renaissance. Mythological elements feature in Renaissance art and in English poems, as well as in film and in other literature, and in songs and commercials. Along with the Bible and the classics-saturated works of Shakespeare, the myths of Greece and Rome have been the major "touchstone" in Western culture for the past 500 years.

Elements appropriated or incorporated include the gods of varying stature, humans, demigods, titans, giants, monsters, nymphs, and famed locations. Their use can range from a brief allusion to the use of an actual Greek character as a character in a work. Some types of creatures—such as centaurs and nymphs—are used as a generic type rather than individuated characters out of myth.

Use by governments and public institutions

Roman conquerors allowed the incorporation of existing Greek mythological figures such as Zeus into their coinage in places like Phrygia, in order to "augment the fame" of the locality, while "creating a stronger civil identity" without "advertising" the imposition of Roman culture.

In modern times, the initial Greek 2 Euro coin featured the myth of Zeus and Europa, and sought to connect the new Europe through Western history to the ancient culture of Greece. As of December 2012, the European Central Bank has plans to incorporate Greek mythological figures into the designs used on its bank notes.

The American colonial revolutionary, Thomas Greenleaf, subtitled his newspaper "The Argus" after the mythological watchman and took the slogan "We Guard the Rights of Man."

The Pegasus appears frequently on stamps, particularly for air mail. In 1906, Greece issued a series of stamps featuring the stories from Hercules' life. Australia commemorated the laying of an underwater cable linking it to the island of Tasmania through a stamp featuring an image of Amphitrite.

The United States military has used Greek mythology to name its equipment such as the Nike missile project and the Navy having over a dozen ships named from Greek mythology. Greek mythology has been the source for names for a number of ships in the British navy, as well as the Australian Royal Navy which has also named a training facility in Victoria called HMAS Cerebus. The Canadair CP-107 Argus of the Royal Canadian Air Force is named in honor of both the hundred eyed Argus Panoptes the "all seeing" and Odysseus' dog Argus who was the only one who identified Odysseus upon his return home.

In science and technology

The elements tantalum and niobium are always found together in nature, and have been named after the King Tantalus and his daughter Niobe. The element promethium also draws its name from Greek mythology, as does titanium, which was named after the titans who in mythology were locked away far underground, which reflected the difficulty of extracting titanium from ore.

Oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau named his research ship, a former British Royal Navy minesweeper, RV Calypso after the sea nymph Calypso. The ship later inspired the John Denver song "Calypso".

The Trojan Horse, a seemingly benign gift that allowed entrance by a malicious force, gave its name to the computer hacking methodology called Trojans.

Biology and medicine

The medical profession is symbolized by the snake-entwined staff of the god of medicine, Asclepius. Today's medical professionals hold a similarly honored position as did the healer-priests of Asclepius.

The Gaia hypothesis proposes that organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a self-regulating, complex system that contributes to maintaining the conditions for life on the planet. The hypothesis was formulated by the scientist James Lovelock and co-developed by the microbiologist Lynn Margulis and was named after Gaia, the mother of the Greek gods.

Astronomy and Astrology

Many celestial bodies have been named after elements of Greek mythology.

- The constellation of Scorpius represents the scorpion that attacked Hercules and the scorpions that frighted the horses when Phaëton was driving the sun-chariot.

- The constellation of Capricorn may represent Pan in a myth that tells of his escape from Typhon by jumping into the water while turning into an animal - the half in the water turned into a fish and the other half turned into a goat.

- 1108 Demeter, a main-belt asteroid discovered by Karl Reinmuth on May 31, 1929, is named after the Greek goddess of fruitful soil and agriculture.

- The U.S. Apollo Space Program to take astronauts to the moon, was named after Apollo, based on the god's ability as an archer to hit his target and being the god of light and knowledge. The people behind this decision apparently did not see the irony in a sun god going to the moon.

Social science

In psychoanalytic theory, the term "Oedipus complex", coined by Sigmund Freud, denotes the emotions and ideas that the mind keeps in the unconscious, via dynamic repression, that concentrate upon a child's desire to sexually possess his/her mother, and kill his/her father. In his later writings Freud postulated an equivalent Oedipus situation for infant girls, the sexual fixation being on the father. Though not advocated by Freud himself, the term 'Electra complex' is sometimes used in this context.

A "Medea complex" is sometimes used to describe parents who murder or otherwise harm their children.

In film and television

Television

- The Battlestar Galactica franchise (particularly the 2004 television series) developed from concepts that utilized Greek mythology.

- Heroes is a series that plays on the concept of the new generation of gods overthrowing the old.

- The television series Lost uses Greek mythology, primarily in its online Lost Experience.

- The television Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and its spin-off Xena: Warrior Princess are set in a fantasy version of ancient Greece and play with the legends, rewriting and updating them for a modern audience.

- The use of Greek mythology in children's television shows is credited with helping to bring "the great symbols of world literature and art" to a mass audience of children who would otherwise have limited exposure. Children's programming has included items such as a recurring segment on CKLW-TV where Don Kolke would be dressed up as Hercules and discuss fitness and Greek mythology.

Film

- Amazons, prior to their appearance in American Hollywood films where they have been presented in "swimsuit-style costume without armor" and "western lingerie combined with various styles of 'tough' male" clothing, had been traditionally depicted in classical Greek warrior armor.

- Jean Cocteau regarded Orpheus as "his myth," and used it as the basis for many projects, including Orphée.

- The film Orfeu Negro is Marcel Camus' reworking of the Cocteau film.

- The 2001 film Moulin Rouge! is also based on the Orpheus story, but set in 1899, and containing modern pop music.

- The Disney production of Hercules (1997) was inspired by Greek myths, but "greatly modernizes the narrative" as it goes "to great lengths to spice up its mythic materials with wacky comedy and cheerfully anachronistic dialogue," which, Keith Booker says, is playing a part in the "slow erosion of historical sense." Moreover, though the film depicts Greek mythology, the title character is named after the Roman hero, rather than the Greek "Heracles".

In games

Tabletop Roleplaying Games

- Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Age of Heroes Campaign Sourcebook (1994).

- Dungeons & Dragons HWR3: The Milenian Empire (1992). A Greek-inspired country within the Hollow World setting.

- Dungeons & Dragons Mythic Odysseys of Theros (2020). Based on the Greek-inspired Theros setting from the Magic: The Gathering collectible card game.

Video Games

- The 1988 arcade game Altered Beast is set in Ancient Greece and follows a player character resurrected by Zeus to rescue his daughter Athena from the ruler of the underworld, Neff.

- The 1996 video game Wrath of the Gods is an adventure game set in mythical Greece, including an educational component where players can learn about Greek myths and history and see images of Greek art in cut-a-ways.

- The 2006 game Persona 3 includes many personae based on mythical Greek figures, using Tartarus in particular as the game's main dungeon.

- In 2003, GameSpy remarked that the 1986 video game Kid Icarus follows a trajectory similar to its namesake, Icarus, who had escaped imprisonment when his father created wings from feathers and wax. The same could be said of the sequel, Kid Icarus: Uprising.

- The God of War franchise of video games is loosely based on Greek mythology, with the main character being named after Kratos (though not the same character). The video game Kratos is a warrior from Sparta and the son of King of the Greek Gods, Zeus and is the personification of power. The series follows Kratos, who initially serves the Gods and later becomes a God himself but later goes on a path of vengeance against them after they betray and try to kill him.

- Koei Tecmo's Warriors Orochi 4 follows a theme of mythology, and is set with combination between Asian Mythology, three kingdoms era, Japanese Warring States period, and Greek Mythology. Characters of this game are also focused in Greek Mythology, such as Zeus, Athena, Perseus, and Ares.

- The Ubisoft game Assassin's Creed Odyssey is set in the mythological history of the Peloponnesian War. The game features a DLC pack titled "Fate of Atlantis" in which Hermes appears, revealing himself to be a member of the precursor race, the Isu.

- The 2020 game Hades places the player in the role of Zagreus to battle out of the underworld with the help of the Olympian gods.

In marketing

- Corporations have used images and concepts from Greek mythology in their logos and in specific advertisements.

- The wine Semeli is named after Semele, who was the mother of the god of wine Dionysus, drawing on the associations to give the product credibility.

- The sports apparel company Nike, Inc. is named after the Greek goddess of victory.

- TriStar Pictures, Readers Digest, and Mobil Oil have used the Pegasus as their corporate logos.

In painting and sculpture

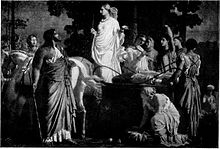

Particularly starting in the Renaissance, artists across Europe produced thousands of works of art depicting the Greek deities and their myths, for reasons ranging from the erudite to the political to the erotic. In particular, in certain periods it was permissible to depict pagan deities nude when it would have been scandalous to so depict a human model or character.

Romans would frequently keep statuary of the Greek god Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and pleasure, in their homes to use as a method of sanctioning relaxation without "any intellectual demands."

Medusa's likeness has been featured by numerous artists including Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin and Benvenuto Cellini.

In literature

Some stories in the Arabian Nights, such as the story of Sinbad blinding a giant, are thought to have been inspired by Greek myths.

In 1816, Percy Shelley had been working on a translation of Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound for Lord Byron. That summer, Shelley and his lover, Mary Godwin, as well as others, stayed with Lord Byron in Switzerland. As a contest, Byron suggested that they each write a ghost story. Mary, who would eventually adopt the name Mary Shelley, began writing her Gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which was declared the winner of the contest. The fact that she overtly subtitled the novel emphasizes Shelley's inspiration from the story of Prometheus, drawing particular attention to the "metaphorical parallels."

In Irish literature, writers such as Seamus Heaney have used the Greek myths to "intertextualize" the actions of the British Government.

Andrew Lang rewrote the tale of Perseus as the anonymous "The Terrible Head" in The Blue Fairy Book.

In C. S. Lewis's retelling of Cupid and Psyche, Till We Have Faces, the narrator is Psyche's sister. Roberta Gellis's Shimmering Splendor is a retelling of Cupid and Psyche.

In poetry

The Italian poet Dante Alighieri used characters from the legend of Troy in his Divine Comedy, placing the Greek heroes in hell to show his contempt for their actions. Poets of the Renaissance began to widely write about Greek mythology, and "elicited as much praise for borrowing or reworking" such material as they did for truly original work. The poet John Milton used figures from classical mythology to "further Christianity: to teach a Christian moral or illustrate a Christian virtue." Euphrosyne, Hymen and Hebe appear in his L'Allegro. Works of Alexander Pope, such as "The Rape of the Lock", parody classical works, even as the income from his translations of Homer allowed him to become "the first English writer to earn a living solely through his literature."

In Ode to a Nightingale, John Keats rejects "charioted by Bacchus and his pards." In his poem "Endymion", the "song of the Indian Maid" recounts how "Bacchus and his crew" interrupted the maid in her solitude. He titled an 1898 narrative poem Lamia.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Oenone" is her lament that Paris deserted her for Helen.

When poets of the German Romantic tradition, such as Friedrich Schiller, wrote about the Greek gods, their works were frequently "erotically charged," as they were "openly sensual and hedonistic."

In "The Waste Land", T. S. Eliot incorporates a range of elements and inspirations from Greek mythology to pop music to Elizabethan history to create a "tour-de-force exposition of Western culture, from the elite to the folk to the utterly primitive." The work of Indian poet Henry Louis Vivian Derozio was heavily influenced by Greek mythology.

Nina Kosman published a book of poems inspired by Greek myths created by poets of the twentieth century from around the world which she intended to show not only the "durability" of the stories but how they are interpreted by "modern sensibility."

In theatre

- The Fortunate Isles and Their Union is a Jacobean era masque, written by Ben Jonson and designed by Inigo Jones, which was first performed on January 9, 1625.

- In William Shakespeare's Macbeth, Hecate appears as the queen of witches, uniquely placing the Anglo-Saxon witches under a Greek goddess's control. Hymen appears as a character name in Shakespeare's As You Like It.

- In 1903, Hugo von Hofmannsthal adopted Sophocles' version of the story of Electra for the stage. Hofmannsthal adapted his work to become the libretto for Richard Strauss' opera Elekra in 1909. The opera, although controversial for both its "modern" music and its depiction of Elektra through "psycho-sexual symbolism," inspired many more adaptations of Electra by other writers and composers during the twentieth century.

- Sartre and Jean Anouilh used Greek myths as inspiration for their plays during the Nazi occupation of France, as the "distancing effect" of the ancient settings allowed their critique to bypass censors. Later, Heiner Müller also used the coding of Greek mythology to disguise his commentaries calling for reform within the German Democratic Republic.

- The Architects (2012) is a play by the London-based Shunts predicated on the myth of the Minotaur, and is about a "return to when Greece was the cradle of civilisation and not about riots on the streets."

- The 2016 stage musical Hadestown, a production with music by Anais Mitchell, follows the stories of Orpheus and Eurydice as well as Hades and Persephone. The show premiered Off-Broadway in 2016, ran at the National Theatre in London in 2018, and is scheduled to have a Broadway run at the Walter Kerr Theatre in March 2019.

In children's and young-adult literature

- In the 19th century, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote children's versions of the Greek myths, which he intended to "entirely revolutionize the whole system of juvenile literature." His work, along with the works of Bulfinch and Kingsley, have been credited with "recast[ing] Greek mythology into a genteel Victorian subject."

- The Percy Jackson & the Olympians series by Rick Riordan follows Percy Jackson as the son of Poseidon. Riordan states that he created the character of Percy when trying to tell a story to help his son who has ADHD get interested in reading. In the stories, Percy's ADHD characteristics are explained as being caused by his Olympian blood, thus Riordan was uses Greek mythology "as it has always been used: to explain something that is difficult to understand."

In comics and graphic novels

- In the opera within Girl Genius, the Heterodyne daughter who falls in love with the Storm King is Euphrosynia.

- The Amazon queen Hippolyta was used as the mother of Wonder Woman in the DC comic book line.

- In 2016 the French philosopher Luc Ferry launched the comic book series La Sagesse des mythes (The Wisdom of the Myths), which retells the Greek myths in a popular form but informed by modern scholarship.

In geography, architecture, and other constructions

- At Niagara Falls, the Bridal Veil Falls had previously been called Iris Falls, and Goat Island had previously been called Iris Island as namesakes of the Greek goddess of the rainbow, Iris, because of the rainbow effects that appear in the mists at the falls. A local newspaper which was published from 1846-1854 was also called The Iris, and the publication The Daily Iris became the Bingham Daily Republican.

- Iapetus Ocean and Rheic Ocean are the names given to the proto-Atlantic Ocean.Francisco de Orellana gave the Amazon river its name after reporting pitched battles with tribes of female warriors, whom he likened to the Amazons.

- The original interior of the Glyptothek, the first public sculpture museum, was adorned with frescoes of Norse mythology by Peter Cornelius and his students which provided a "lively dialogue" between the building and its contents. When the building was repaired after war-time damage, the frescoes were not restored.

- Brookside, also known as the John H. Bass Mansion, has the Muses decorating the ceiling around the skylight in its ballroom. In Philadelphia, the Masonic Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania's Corinthian Hall is decorated with feathers to Greek mythology.

- The MGR Samadhi Memorial in Chennai, India, was redecorated in 2012 to include a pegasus, which symbolized "valour and energy."

- Hydra the Revenge is a Bolliger & Mabillard designed floorless roller coaster at Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom in Allentown, Pennsylvania with a Lernaean Hydra theme. The name of the ride pays tribute to the "Hercules" wooden roller coaster that once stood on the same spot. The theme itself is the Hydra coming back to life and seeking revenge over Hercules.

In music

- According to some sources, Caribbean Calypso music is named after the Greek nymph Calypso, though this is not universally accepted.

- Musical parodist Peter Schickele created the opera Iphigenia in Brooklyn by P D Q Bach, in which Iphigenia has traveled to the New World.

- Heavy metal band The Lord Weird Slough Feg included two songs, written by the band and influenced by Homer's Odyssey on their 2005 album Atavism.

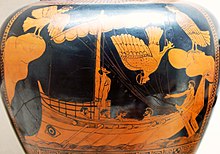

- The Greek myths have been the inspiration for a number of operas. Claudio Monteverdi and Giacomo Badoaro used a Greek text about the homecoming of Odysseus as the basis for Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria over which they attempted to overlay Christian beliefs and create in Zeus an omnipotent and merciful being. Cherubini's Médée takes the story which had been portrayed in many version on the French stage as a melodrama, and instead portrays Medea as a tragic heroine who deserves the audiences' sympathy.

Rejection of use

During the Middle Ages, writers disdained the use of "pagan" influences such as Greek mythology which were seen to be a "slight to Christianity." From a current cultural perspective, the Greek Orthodox metropolitan Agustinos Kantiotis has denounced the use of Greek mythology such as the use of Hermes on a postage stamp and the incorporation of images from Greek mythology into universities' logos and buildings.

Greek women poets of the modern era; such as Maria Polydouri, Pavlina Pamboudi, Myrtiotissa, Melissanthi and Rita Boumi-Pappa; rarely use mythological references, which Christopher Robinson attributes to the "problem of gender roles, both inside and outside the myths."

Martin Winter says that the idea that many commentaries about the widespread use of Greek myths throughout Western culture does not take into account the vast difference between what a modern viewer takes from the story and what it would have meant to an ancient Greek.