The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday or The Day of the Lord (Hebrew: יום הדין, romanized: Yom ha-din, Arabic: یوم القيامة, romanized: Yawm al-qiyāmah, lit. 'Day of Resurrection' or Arabic: یوم الدین, romanized: Yawm ad-din, lit. 'Day of Judgement') is part of the eschatology of the Abrahamic religions and in the Frashokereti of Zoroastrianism.

Some Christian denominations consider the Second Coming of Christ to be the final and infinite judgment by God of the people of every nation resulting in the approval of some and the penalizing of others. The concept is found in all the canonical gospels, particularly the Gospel of Matthew. Christian Futurists believe it will take place after the resurrection of the dead and the Second Coming of Christ while Full Preterists believe it has already occurred. The Last Judgment has inspired numerous artistic depictions.

In the Baha'i Faith

The Bab and Baha'u'llah taught that there is one unfolding religion of one God and that once in about every 1,000 years a new messenger prophet, Rasul al-Nabii, or as Baha'is call them, Manifestation of God, comes to mankind to renew the Kingdom of God on earth and establish a new Covenant between humanity and God. Each time a new Manifestation of God comes it is considered the Day of Judgment, Day of Resurrection, or 'the Last Hour' for the believers and unbelievers of the previous Manifestation of God. The Bab told of the judgment:

There shall be no resurrection of the day, in the sense of the coming forth from the physical graves. Rather, the resurrection of all shall occur (in the form of) those that are living in that age. If they belong to paradise, they shall be believers, if to hell, they shall be unbelievers. There is no denying that upon the Day of Resurrection, each and every thing shall be raised to life before God, may he be praised and glorified. For God shall originate that creation and then cause it to return. He has decreed the creation of all things, and he shall raise them to life again. God is powerful over all things.

According to Baha'is, the coming of The Bab is the promised Mahdi and Qaim, and the coming of Baha'u'llah is the return of Christ through his revelation, which respectively signify the Day of Judgment foretold by Muhammad and the Day of Resurrection foretold by the Bayan.

Future Day of Judgment

Baha'u'llah wrote in the Kitab-i-Aqdas: "Whoso layeth claim to Revelation direct from God, ere the expiration of a full thousand years, such a man is assuredly a lying imposter." The thousand years is calculated from beginning in October 1852 CE, when Bahaullah received a message in the Siyah-Chal from the Maid of Heaven, and they could refer to either lunar or solar years, which associate to roughly the Islamic Year of 2269 AH/2823 CE, or, 2853 CE/2300 AH.

The Bab wrote, "He Who will shine resplendent in the Day of Resurrection is the inner reality enshrined in the Point of the Bayan". This is that which Baha'is believe referred to Baha'u'llah being the inner reality of The Bab. The 'Point of the Bayan' refers to The Bab Himself. However, in al-Kafi Volume 2, this 'Point' would refer to directly to Baha'u'llah with the Bab being the Point of the Quran. Moreover, according to valid Bahai conjecture of al-Kafi Volume 2, the Point of the Most Great Name could only be from the Afnan or Aghsan just as the Qaim needed to be a descendant of Muhammad. However, the Kitab-i-Aqdas states, "Beware lest any name debar you from Him Who is the Possessor of all names". Additionally, Baha'u'llah warned not to be dismayed if the next Revelation, direct from God, is from a Nabi, Prophet, that is ominous of a lack of a Rasul al-Nabii coming. However, the Bab foretold of One like unto Him coming again after His Dispensation, which could mean that the next Prophet could slowly unveil Him/Herself in stages. Also, in the Kitab-i-Iqan, Baha'u'llah revealed that every Dispensation's Messenger is rejected using the Scriptures of the past because "every subsequent Revelation hath abolished the manners, habits, and teachings that have been clearly, specifically, and firmly established by the former Dispensation". Based on Hadith 3455, alKafi, a valid Prophet would be the foremost in virtue and deeds among the Baha'is of that time period, and her/his Word of truth would abrogate Baha'u'llah's Revelation.

It is noteworthy to call to mind the Hadith of one who asked an A'immah about meeting the Qa'im. The Imam asked him if he knew who his Imam was to which the man responded "it is you". "The Imam said, 'Then you must not worry about not leaning against your sword in the shadow of the tent of the Qa'im, 'Alayhi al-Salam.'" Also, Baha'u'llah warned that "Erelong shall clamorous voices be raised in most lands." referring to people believing they have a direct Revelation from God before the thousand-year period is complete. Further, Abdu'l-Baha states, “The East has ever been the dawning point of the Sun of Reality. All the Prophets of God have appeared there. The religions of God have been promulgated, the teachings of God have been spread, and the law of God founded in the East. The Orient has always been the center of lights”. Moreover, the Bab stated that one who does not recognize each succeeding Messenger goes even more astray than those who refused to acknowledge a previous Messenger. Also, Abdu'l-Baha wrote that the Manifestations of God have claircognizance; however, the Prophet to come will not be a Universal Manifestation. Therefore, the outward psychic powers of the Prophet could be different. Furthermore, Abdu'l-Baha stated that more than one Prophet could arise after the 1000-year period Who have direct Revelation. Also, what is most important to keep in mind is Baha'u'llah's warning that God "doeth what He willeth, and ordaineth as He pleaseth". This means at each Judgment Day were God to completely change meanings like earth to be heaven or pronounce unbelief to be belief, it is in His power.

Future disbelief

The disbelief raised in the coming Age will be based on the doubt/belief that Abdu'l-Baha is meant to be the lone successor of Baha'u'llah. It can already be discerned in the following verses all taken from The World Order of Baha'u'llah by Shoghi Effendi: "The Abha Beauty is the supreme Manifestation of God. ...All others are servants unto Him and do His bidding". "When the ocean of My presence hath ebbed and the Book of My Revelation is ended turn your faces towards Him Whom God hath purposed, Who hath branched from this Ancient Root". "There hath branched from the Sadratu'l-Muntaha ... He is the Trust of God amongst you, His charge within you, His Manifestation unto you". "They who deprive themselves of the shadow of the Branch, are lost in the wilderness of error". "Ordaineth ... for Him (Abdu'l-Baha) ... that which Thou hast destined for The Messengers and the Trustees of The Revelation". "Whoso deviateth from My interpretation is a victim of his own fancy". "In all the Divine Dispensations the eldest son hath been given extraordinary distinctions. Even the station of prophethood hath been his birthright". "Whoso doth deviate therefrom (the Universal House of Justice) is verily of them that love discord, hath shown forth malice, and turned away from the Lord of the Covenant".

Linked together, all these quotes foretell of people who, clinging to doubt, will believe that Abdu'l-Baha is the One foretold to lead after the 1,000-year period, just as a Prophet would, instead of a new Prophet with an entirely new Covenant. Although there are many quotes that can dispel this doubt, just as Christians today, they will circumvent truth with falsehood.

Also, the quote: "Manifestations that will come down in the future 'in the shadow of the clouds'", will become interpreted to mean more of a universal revelation, or, a spiritual interpretation, instead of the obvious meaning of a physically new Prophet.

In Christianity

Biblical sources

The doctrine and iconographic depiction of the "Last Judgment" are drawn from many passages from the apocalyptic sections of the Bible, but most notably from Jesus' teaching of the strait gate in the Gospel of Matthew and also found in the Gospel of Luke:

Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat: Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep's clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves. Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles? Even so, every good tree bringeth forth good fruit; but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit. Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire. Therefore, by their fruits ye shall know them. Not every one that saith unto me: Lord, Lord, shall enter into the Kingdom of Heaven; but he that doeth the will of my Father which is in heaven. Many will say to me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in thy name? and in thy name have cast out devils? and in thy name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity. (Matthew 7:13–23)

Then said one unto him, Lord, are there few that be saved? And he said unto them, Strive to enter in at the strait gate: for many, I say unto you, will seek to enter in, and shall not be able. When once the master of the house is risen up, and hath shut to the door, and ye begin to stand without, and to knock at the door, saying, Lord, Lord, open unto us; and he shall answer and say unto you, I know you not whence ye are: Then shall ye begin to say, We have eaten and drunk in thy presence, and thou hast taught in our streets. But he shall say, I tell you, I know you not whence ye are; depart from me, all ye workers of iniquity. There shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth, when ye shall see Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, and all the prophets, in the kingdom of God, and you yourselves thrust out. (Luke 13:23–28)

It also appears in the Sheep and the Goats section of Matthew where the judgment seems entirely based on help given or refused to "one of the least of these my brethren" who are identified in Matthew 12 as "whosoever shall do the will of my Father which is in heaven".

When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, "Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me." (Matthew 25:31–36),

And the king will answer them, "Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’ Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You that are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels; for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me." (Matthew 25:40–43)

Then he will answer them, "Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life." (Matthew 25:45–46)

The doctrine is further supported by passages in the Books of Daniel, Isaiah and the Revelation:

Then I saw a great white throne and him who was seated on it. From his presence earth and sky fled away, and no place was found for them. And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Then another book was opened, which is the book of life. And the dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to what they had done. (Rev 20:11–12)

As I watched, thrones were set in place, and an Ancient One[a] took his throne; his clothing was white as snow, and the hair of his head like pure wool; his throne was fiery flames, and its wheels were burning fire. A stream of fire issued and flowed out from his presence. A thousand thousand served him, and ten thousand times ten thousand stood attending him. The court sat in judgement, and the books were opened. (Daniel 7: 9-10)

Even now the axe is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. "I baptize you with water for repentance, but one who is more powerful than I is coming after me; I am not worthy to carry his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing-floor and will gather his wheat into the granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire." (Matthew 3:10–12)

Just as the weeds are collected and burned up with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. Let anyone with ears listen! (Matthew 13:40–43)

I tell you, my friends, do not fear those who kill the body, and after that can do nothing more. But I will warn you whom to fear: fear him who, after he has killed, has authority to cast into hell. Yes, I tell you, fear him! (Luke 12:4–5)

Amillennialism

Amillennialism is the standard view in Christian denominations such as the Anglican, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Methodist and Presbyterian/Reformed Churches. It holds that "the kingdom of God is present in the church age", and that the millennium mentioned in the Book of Revelation is a "symbol of the saints reigning with Christ forever in victory."

Anglicanism and Methodism

Article IV – Of the Resurrection of Christ in Anglicanism's Articles of Religion and Article III – Of the Resurrection of Christ of Methodism's Articles of Religion state that:

Christ did truly rise again from death, and took again his body, with flesh, bones, and all things appertaining to the perfection of Man's nature; wherewith he ascended into Heaven, and there sitteth, until he return to judge all Men at the last day.

As such, Anglican and Methodist theology holds that "there is an intermediate state between death and the resurrection of the dead, in which the soul does not sleep in unconsciousness, but exists in happiness or misery till the resurrection, when it shall be reunited to the body and receive its final reward." This space, termed Hades, is divided into Paradise (the Bosom of Abraham) and Gehenna "but with an impassable gulf between the two". Souls remain in Hades until the Last Judgment and "Christians may also improve in holiness after death during the middle state before the final judgment."

Anglican and Methodist theology holds that at the time of the Last Day, "Jesus will return and that He will 'judge both the quick and the dead'," and "all [will] be bodily resurrected and stand before Christ as our Judge. After the Judgment, the Righteous will go to their eternal reward in heaven and the Accursed will depart to hell (see Matthew 25)." The "issue of this judgment shall be a permanent separation of the evil and the good, the righteous and the wicked" (see The Sheep and the Goats). Moreover, in "the final judgment every one of our thoughts, words, and deeds will be known and judged" and individuals will be justified on the basis of their faith in Jesus, although "our works will not escape God's examination."

Catholicism

Belief in the Last Judgment (often linked with the General judgment) is held firmly in Catholicism. Immediately upon death each person undergoes the particular judgment, and depending upon one's behavior on earth, goes to heaven, purgatory, or hell. Those in purgatory will always reach heaven, but those in hell will be there eternally.

The Last Judgment will occur after the resurrection of the dead and "our 'mortal body' will come to life again." The Catholic Church teaches that at the time of the Last Judgment Christ will come in His glory, and all the angels with him, and in his presence the truth of each one's deeds will be laid bare, and each person who has ever lived will be judged with perfect justice. The believers who are judged worthy as well as those ignorant of Christ's teaching who followed the dictates of conscience will go to everlasting bliss, and those who are judged unworthy will go to everlasting condemnation.

A decisive factor in the Last Judgement will be the question, were the corporal works of mercy practiced or not during one's lifetime. They rate as important acts of charity. Therefore, and according to the biblical sources (Mt 25:31–46), the conjunction of the Last Judgement and the works of mercy is very frequent in the pictorial tradition of Christian art.

Before the Last Judgment, all will be resurrected. Those who were in purgatory will have already been purged, meaning they would have already been released into heaven, and so like those in heaven and hell will resurrect with their bodies, followed by the Last Judgment.

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

1038 The resurrection of all the dead, "of both the just and the unjust" (Acts 24:15), will precede the Last Judgment. This will be "the hour when all who are in the tombs will hear [the Son of man's] voice and come forth, those who have done good, to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil, to the resurrection of judgment" (Jn 5:28-29) Then Christ will come "in his glory, and all the angels with him. . . . Before him will be gathered all the nations, and he will separate them one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will place the sheep at his right hand, but the goats at the left. . . . And they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life (Mt 25:31,32,46)."

1039 In the presence of Christ, who is Truth itself, the truth of each man's relationship with God will be laid bare (Cf. Jn 12:4). The Last Judgment will reveal even to its furthest consequences the good each person has done or failed to do during his earthly life.

1040 The Last Judgment will come when Christ returns in glory. Only the Father knows the day and the hour; only he determines the moment of its coming. Then through his Son Jesus Christ he will pronounce the final word on all history. We shall know the ultimate meaning of the whole work of creation and of the entire economy of salvation and understand the marvelous ways by which his Providence led everything towards its final end. The Last Judgment will reveal that God's justice triumphs over all the injustices committed by his creatures and that God's love is stronger than death. (Cf. Song 8:6)

The Eastern Orthodox and Catholic teachings of the Last Judgment differ only on the exact nature of the in-between state of purgatory/Abraham's Bosom. These differences may only be apparent and not actual due to differing theological terminology and evolving tradition.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Eastern Orthodox Church teaches that there are two judgments: the first, or "Particular" Judgment, is that experienced by each individual at the time of his or her death, at which time God will decide where one is to spend the time until the Second Coming of Christ (see Hades in Christianity). This judgment is generally believed to occur on the fortieth day after death. The second, "General" or "Final" Judgment will occur after the Second Coming.

Although in modern times some have attempted to introduce the concept of soul sleep into Orthodox thought about life after death, it has never been a part of traditional Orthodox teaching, and it even contradicts the Orthodox understanding of the intercession of the Saints.

Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that salvation is bestowed by God as a free gift of divine grace, which cannot be earned, and by which forgiveness of sins is available to all. However, the deeds done by each person are believed to affect how he will be judged, following the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats. How forgiveness is to be balanced against behavior is not well-defined in scripture, judgment in the matter being solely Christ's.

Similarly, although Orthodoxy teaches that salvation is obtained only through Christ and his Church, the fate of those outside the Church at the Last Judgment is left to the mercy of God and is not declared.

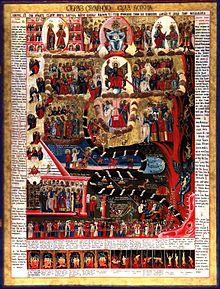

Icons

The theme of the Last Judgment is extremely important in Orthodoxy. Traditionally, an Orthodox church will have a fresco or mosaic of the Last Judgment on the back (western) wall so that the faithful, as they leave the services, are reminded that they will be judged by what they do during this earthly life.

The icon of the Last Judgment traditionally depicts Christ Pantokrator, enthroned in glory on a white throne, surrounded by the Theotokos (Virgin Mary), John the Baptist, Apostles, saints and angels. Beneath the throne the scene is divided in half with the "mansions of the righteous" (John 14:2), i.e., those who have been saved, to Jesus' right (the viewer's left), and the torments of those who have been damned to his left. Separating the two is the river of fire which proceeds from Jesus' left foot. For more detail, see below.

Hymnography

The theme of the Last Judgment is found in the funeral and memorial hymnody of the Church, and is a major theme in the services during Great Lent. The second Sunday before the beginning of Great Lent is dedicated to the Last Judgment. It is also found in the hymns of the Octoechos used on Saturdays throughout the year.

Lutheranism

Lutherans do not believe in any sort of earthly millennial kingdom of Christ either before or after his second coming on the last day. On the last day, all the dead will be resurrected. Their souls will then be reunited with the same bodies they had before dying. The bodies will then be changed, those of the wicked to a state of everlasting shame and torment, those of the righteous to an everlasting state of celestial glory. After the resurrection of all the dead, and the change of those still living, all nations shall be gathered before Christ, and he will separate the righteous from the wicked. Christ will publicly judge all people by the testimony of their faith – the good works of the righteous in evidence of their faith, and the evil works of the wicked in evidence of their unbelief. He will judge in righteousness in the presence of all and men and angels, and his final judgement will be just damnation to everlasting punishment for the wicked and a gracious gift of life everlasting to the righteous.

Esoteric Christian tradition

Although the Last Judgment is preached by a great part of Christian mainstream churches; the Esoteric Christian traditions like the Essenes and Rosicrucians, the Spiritualist movement, and some liberal theologies reject the traditional conception of the Last Judgment, as inconsistent with an all-just and loving God, in favor of some form of universal salvation.

Max Heindel, a Danish-American astrologer and mystic, taught that when the Day of Christ comes, marking the end of the current fifth or Aryan epoch, the human race will have to pass a final examination or last judgment, where, as in the Days of Noah, the chosen ones or pioneers, the sheep, will be separated from the goats or stragglers, by being carried forward into the next evolutionary period, inheriting the ethereal conditions of the New Galilee in the making. Nevertheless, it is emphasized that all beings of the human evolution will ultimately be saved in a distant future as they acquire a superior grade of consciousness and altruism. At the present period, the process of human evolution is conducted by means of successive rebirths in the physical world and the salvation is seen as being mentioned in Revelation 3:12 (KJV), which states "Him that overcometh will I make a pillar in the temple of my God and he shall go no more out". However, this western esoteric tradition states – like those who have had a near-death experience – that after the death of the physical body, at the end of each physical lifetime and after the life review period (which occurs before the silver cord is broken), a judgment occurs, more akin to a Final Review or End Report over one's life, where the life of the subject is fully evaluated and scrutinized. This judgment is seen as being mentioned in Hebrews 9:27, which states that "it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment".

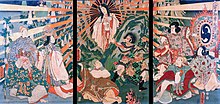

Artistic representations

In art, the Last Judgment is a common theme in medieval and renaissance religious iconography. Like most early iconographic innovations, its origins stem from Byzantine art, although it was a much less common subject than in the West during the Middle Ages. In Western Christianity, it is often the subject depicted in medieval cathedrals and churches, either outside on the central tympanum of the entrance or inside on the (rear) west wall, so that the congregation attending church saw the image on either entering of leaving.

In the 15th century it also appeared as the central section of a triptych on altarpieces, with the side panels showing heaven and hell, as in the Beaune Altarpiece or a triptych by Hans Memling. The usual composition has Christ seated high in the centre, flanked by angels, the Virgin Mary, and John the Evangelist who are supplicating on behalf of those being judged (in what is called a Deesis group in Orthodoxy). Saint Michael is often shown, either weighing the deceased on scales or directing matters, and there might be a large crowd of saints, angels, and the saved around the central group.

At the bottom of the composition a crowd of the deceased are shown, often with some rising from their graves. These are being sorted and directed by angels into the saved and the damned. Almost always the saved are on the viewer's left (so on the right hand of Christ), and the damned on the right. The saved are led up to heaven, often shown as a fortified gateway, while the damned are handed over to devils who herd them down into hell on the right; the composition therefore has a circular pattern of movement. Often the damned disappear into a Hellmouth, the mouth of a huge monster, an image of Anglo-Saxon origin. The damned often include figures of high rank, wearing crowns, mitres, and often the Papal tiara during the lengthy periods when there were antipopes, or in Protestant depictions. There may be detailed depictions of the torments of the damned.

The most famous Renaissance depiction is Michelangelo Buonarroti's The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Included in this fresco is his self-portrait, as St. Bartholomew's flayed skin.[74]

The image in Eastern Orthodox icons has a similar composition, but usually less space is devoted to hell, and there are often a larger number of scenes; the Orthodox readiness to label figures with inscriptions often allows more complex compositions. There is more often a large group of saints around Christ (which may include animals), and the hetoimasia or "empty throne", containing a cross, is usually shown below Christ, often guarded by archangels; figures representing Adam and Eve may kneel below it or below Christ. A distinctive feature of the Orthodox composition, especially in Russian icons, is a large band leading like a chute from the feet of Christ down to hell; this may resemble a striped snake or be a "river of Fire" coloured flame red. If it is shown as a snake, it attempts to bite Adam on the heel but, as he is protected by Christ, is unsuccessful.

Swedenborgian

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) had a revelation that the church has gone through a series of Last Judgments. First, during Noah's Flood, then Moses on Mount Sinai, Jesus' crucifixion, and finally in 1757, which is the final Last Judgment. These occur in a realm outside earth and heaven, and are spiritual in nature.

In Islam

According to Islamic eschatology, the Day of Resurrection (yawm al-qiyāmah) is believed to be God's final assessment of humanity. The sequence of events (according to the most commonly held belief) is the annihilation of all creatures, resurrection of the body, and the judgment of all sentient creatures. It is a time where everyone would be shown his or her deeds and actions with justice.

The exact time when these events will occur is unknown, however there are said to be major and minor signs which are to occur near the time of Qiyammah (end time). It is believed that prior to the time of Qiyammah, two dangerous, evil tribes called Yajooj and Majooj are released from a dam-resembling wall that Allah makes stronger everyday. Other signs are mentioned like the blowing of the first trumpet by an archangel Israfil, and the coming of rain of mercy that will cause humans to grow from a tiny part of their tailbone, which was said to never degenerate, even in the grave, despite the decay of the human body. Many verses of the Quran, especially the earlier ones, are dominated by the idea of the nearing of the Day of Resurrection.

Belief in Judgment Day is considered a fundamental tenet of faith by all Muslims. It is one of the six articles of faith. The trials and tribulations associated with it are detailed in both the Quran and the hadith, sayings of Muhammad. Hence they were added in the commentaries of the Islamic expositors and scholarly authorities such as al-Ghazali, Ibn Kathir, Ibn Majah, Muhammad al-Bukhari, and Ibn Khuzaymah who explain them in detail. Every human, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, is believed to be held accountable for their deeds and are believed to be judged by God accordingly.

In Judaism

In Judaism, beliefs vary about a last day of judgment for all mankind. Some rabbis hold that there will be such a day following the resurrection of the dead. Others hold that this accounting and judgment happens when one dies. Still others hold that the last judgment only applies to the gentiles and not the Jewish people.

In Zoroastrianism

Frashokereti is the Zoroastrian doctrine of a final renovation of the universe, when evil will be destroyed, and everything else will be then in perfect unity with God (Ahura Mazda).

The doctrinal premises are (1) good will eventually prevail over evil; (2) creation was initially perfectly good, but was subsequently corrupted by evil; (3) the world will ultimately be restored to the perfection it had at the time of creation; (4) the "salvation for the individual depended on the sum of [that person's] thoughts, words and deeds, and there could be no intervention, whether compassionate or capricious, by any divine being to alter this." Thus, each human bears responsibility for their own fate, and simultaneously shares in the responsibility for the fate of the world.

Crack of doom

In English, crack of doom is an old term used for the Day of Judgement, referring in particular to the blast of trumpets signalling the end of the world in Chapter 8 of the Book of Revelation. A "crack" had the sense of any loud noise, preserved in the phrase "crack of thunder", and "doom" was a term for the Last Judgement, as doomsday still is.

The phrase is famously used by William Shakespeare in Macbeth, where on the heath the Three Witches show Macbeth the line of kings that will issue from Banquo:

- "Why do you show me this? A fourth! Start, eyes!

- What, will the line stretch out to the crack of doom?

- Another yet! A seventh! I'll see no more." (Act 4, scene 1, 112–117)

The meaning was that Banquo's line will endure until the Judgement Day, flattery for King James I, who claimed descent from Banquo.

Music

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Extremum Dei Judicium H.401, Oratorio for soloists, chorus, 2 treble instruments, and continuo. (1680)

Giacomo Carissimi, Extremum Dei Judicium, for 3 chorus, 2 violins and organ.