Cognitive biology is an emerging science that regards natural cognition as a biological function. It is based on the theoretical assumption that every organism—whether a single cell or multicellular—is continually engaged in systematic acts of cognition coupled with intentional behaviors, i.e., a sensory-motor coupling. That is to say, if an organism can sense stimuli in its environment and respond accordingly, it is cognitive. Any explanation of how natural cognition may manifest in an organism is constrained by the biological conditions in which its genes survive from one generation to the next. And since by Darwinian theory the species of every organism is evolving from a common root, three further elements of cognitive biology are required: (i) the study of cognition in one species of organism is useful, through contrast and comparison, to the study of another species’ cognitive abilities; (ii) it is useful to proceed from organisms with simpler to those with more complex cognitive systems, and (iii) the greater the number and variety of species studied in this regard, the more we understand the nature of cognition.

Overview

While cognitive science endeavors to explain human thought and the conscious mind, the work of cognitive biology is focused on the most fundamental process of cognition for any organism. In the past several decades, biologists have investigated cognition in organisms large and small, both plant and animal. “Mounting evidence suggests that even bacteria grapple with problems long familiar to cognitive scientists, including: integrating information from multiple sensory channels to marshal an effective response to fluctuating conditions; making decisions under conditions of uncertainty; communicating with conspecifics and others (honestly and deceptively); and coordinating collective behaviour to increase the chances of survival.” Without thinking or perceiving as humans would have it, an act of basic cognition is arguably a simple step-by-step process through which an organism senses a stimulus, then finds an appropriate response in its repertoire and enacts the response. However, the biological details of such basic cognition have neither been delineated for a great many species nor sufficiently generalized to stimulate further investigation. This lack of detail is due to the lack of a science dedicated to the task of elucidating the cognitive ability common to all biological organisms. That is to say, a science of cognitive biology has yet to be established. A prolegomena for such science was presented in 2007 and several authors have published their thoughts on the subject since the late 1970s. Yet, as the examples in the next section suggest, there is neither consensus on the theory nor widespread application in practice.

Although the two terms are sometimes used synonymously, cognitive biology should not be confused with the biology of cognition in the sense that it is used by adherents to the Chilean School of Biology of Cognition. Also known as the Santiago School, the biology of cognition is based on the work of Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana, who crafted the doctrine of autopoiesis. Their work began in 1970 while the first mention of cognitive biology by Brian Goodwin (discussed below) was in 1977 from a different perspective.

History

'Cognitive biology' first appeared in the literature as a paper with that title by Brian C. Goodwin in 1977. There and in several related publications Goodwin explained the advantage of cognitive biology in the context of his work on morphogenesis. He subsequently moved on to other issues of structure, form, and complexity with little further mention of cognitive biology. Without an advocate, Goodwin's concept of cognitive biology has yet to gain widespread acceptance.

Aside from an essay regarding Goodwin's conception by Margaret Boden in 1980, the next appearance of ‘cognitive biology’ as a phrase in the literature came in 1986 from a professor of biochemistry, Ladislav Kováč. His conception, based on natural principles grounded in bioenergetics and molecular biology, is briefly discussed below. Kováč's continued advocacy has had a greater influence in his homeland, Slovakia, than elsewhere partly because several of his most important papers were written and published only in Slovakian.

By the 1990s, breakthroughs in molecular, cell, evolutionary, and developmental biology generated a cornucopia of data-based theory relevant to cognition. Yet aside from the theorists already mentioned, no one was addressing cognitive biology except for Kováč.

Kováč’s cognitive biology

Ladislav Kováč's “Introduction to cognitive biology” (Kováč, 1986a) lists ten ‘Principles of Cognitive Biology.’ A closely related thirty page paper was published the following year: “Overview: Bioenergetics between chemistry, genetics and physics.” (Kováč, 1987). Over the following decades, Kováč elaborated, updated, and expanded these themes in frequent publications, including "Fundamental principles of cognitive biology" (Kováč, 2000), “Life, chemistry, and cognition” (Kováč, 2006a), "Information and Knowledge in Biology: Time for Reappraisal” (Kováč, 2007) and "Bioenergetics: A key to brain and mind" (Kováč, 2008).

Academic usage

University seminar

The concept of cognitive biology is exemplified by this seminar description:

Cognitive science has focused primarily on human cognitive activities. These include perceiving, remembering and learning, evaluating and deciding, planning actions, etc. But humans are not the only organisms that engage in these activities. Indeed, virtually all organisms need to be able to procure information both about their own condition and their environment and regulate their activities in ways appropriate to this information. In some cases species have developed distinctive ways of performing cognitive tasks. But in many cases these mechanisms have been conserved and modified in other species. This course will focus on a variety of organisms not usually considered in cognitive science such as bacteria, planaria, leeches, fruit flies, bees, birds and various rodents, asking about the sorts of cognitive activities these organisms perform, the mechanisms they employ to perform them, and what lessons about cognition more generally we might acquire from studying them.

University workgroup

The University of Adelaide has established a "Cognitive Biology" workgroup using this operating concept:

Cognition is, first and foremost, a natural biological phenomenon — regardless of how the engineering of artificial intelligence proceeds. As such, it makes sense to approach cognition like other biological phenomena. This means first assuming a meaningful degree of continuity among different types of organisms—an assumption borne out more and more by comparative biology, especially genomics—studying simple model systems (e.g., microbes, worms, flies) to understand the basics, then scaling up to more complex examples, such as mammals and primates, including humans.

Members of the group study the biological literature on simple organisms (e.g., nematode) in regard to cognitive process and look for homologues in more complex organisms (e.g., crow) already well studied. This comparative approach is expected to yield simple cognitive concepts common to all organisms. “It is hoped a theoretically well-grounded toolkit of basic cognitive concepts will facilitate the use and discussion of research carried out in different fields to increase understanding of two foundational issues: what cognition is and what cognition does in the biological context.” (Bold letters from original text.)

The group's choice of name, as they explain on a separate webpage, might have been ‘embodied cognition’ or ‘biological cognitive science.’ But the group chose ‘cognitive biology’ for the sake of (i) emphasis and (ii) method. For the sake of emphasis, (i) “We want to keep the focus on biology because for too long cognition was considered a function that could be almost entirely divorced from its physical instantiation, to the extent that whatever could be said of cognition almost by definition had to be applicable to both organisms and machines.” (ii) The method is to “assume (if only for the sake of enquiry) that cognition is a biological function similar to other biological functions—such as respiration, nutrient circulation, waste elimination, and so on.”

The method supposes that the genesis of cognition is biological, i.e., the method is biogenic. The host of the group's website has said elsewhere that cognitive biology requires a biogenic approach, having identified ten principles of biogenesis in an earlier work. The first four biogenic principles are quoted here to illustrate the depth at which the foundations have been set at the Adelaide school of cognitive biology:

- “Complex cognitive capacities have evolved from simpler forms of cognition. There is a continuous line of meaningful descent.”

- “Cognition directly or indirectly modulates the physico-chemical-electrical processes that constitute an organism .”

- “Cognition enables the establishment of reciprocal causal relations with an environment, leading to exchanges of matter and energy that are essential to the organism’s continued persistence, well-being or replication.”

- “Cognition relates to the (more or less) continuous assessment of system needs relative to prevailing circumstances, the potential for interaction, and whether the current interaction is working or not.”

Other universities

- As another example, the Department für Kognitionsbiologie at the University of Vienna declares in its mission statement a strong commitment “to experimental evaluation of multiple, testable hypotheses” regarding cognition in terms of evolutionary and developmental history as well as adaptive function and mechanism, whether the mechanism is cognitive, neural, and/or hormonal. “The approach is strongly comparative: multiple species are studied, and compared within a rigorous phylogenetic framework, to understand the evolutionary history and adaptive function of cognitive mechanisms (‘cognitive phylogenetics’).” Their website offers a sample of their work: “Social Cognition and the Evolution of Language: Constructing Cognitive Phylogenies.”

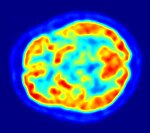

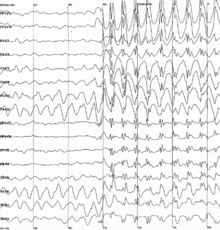

- A more restricted example can be found with the Cognitive Biology Group, Institute of Biology, Faculty of Science, Otto-von-Guericke University (OVGU) in Magdeburg, Germany. The group offers courses titled “Neurobiology of Consciousness” and “Cognitive Neurobiology.” Its website lists the papers generated from its lab work, focusing on the neural correlates of perceptual consequences and visual attention. The group's current work is aimed at detailing a dynamic known as ‘multistable perception.’ The phenomenon, described in a sentence: “Certain visual displays are not perceived in a stable way but, from time to time and seemingly spontaneously, their appearance wavers and settles in a distinctly different form.”

- A final example of university commitment to cognitive biology can be found at Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia. There in the Faculty of Natural Sciences, the Bratislava Biocenter is presented as a consortium of research teams working in biomedical sciences. Their website lists the Center for Cognitive Biology in the Department of Biochemistry at the top of the page, followed by five lab groups, each at a separate department of bioscience. The webpage for the Center for Cognitive Biology offers a link to "Foundations of Cognitive Biology," a page that simply contains a quotation from a paper authored by Ladislav Kováč, the site's founder. His perspective is briefly discussed below.

Cognitive biology as a category

The words ‘cognitive’ and ‘biology’ are also used together as the name of a category. The category of cognitive biology has no fixed content but, rather, the content varies with the user. If the content can only be recruited from cognitive science, then cognitive biology would seem limited to a selection of items in the main set of sciences included by the interdisciplinary concept—cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence, linguistics, philosophy, neuroscience, and cognitive anthropology. These six separate sciences were allied “to bridge the gap between brain and mind” with an interdisciplinary approach in the mid-1970s. Participating scientists were concerned only with human cognition. As it gained momentum, the growth of cognitive science in subsequent decades seemed to offer a big tent to a variety of researchers. Some, for example, considered evolutionary epistemology a fellow-traveler. Others appropriated the keyword, as for example Donald Griffin in 1978, when he advocated the establishment of cognitive ethology.

Meanwhile, breakthroughs in molecular, cell, evolutionary, and developmental biology generated a cornucopia of data-based theory relevant to cognition. Categorical assignments were problematic. For example, the decision to append cognitive to a body of biological research on neurons, e.g. the cognitive biology of neuroscience, is separate from the decision to put such body of research in a category named cognitive sciences. No less difficult a decision needs be made—between the computational and constructivist approach to cognition, and the concomitant issue of simulated v. embodied cognitive models—before appending biology to a body of cognitive research, e.g. the cognitive science of artificial life.

One solution is to consider cognitive biology only as a subset of cognitive science. For example, a major publisher's website displays links to material in a dozen domains of major scientific endeavor. One of which is described thus: “Cognitive science is the study of how the mind works, addressing cognitive functions such as perception and action, memory and learning, reasoning and problem solving, decision-making and consciousness.” Upon its selection from the display, the Cognitive Science page offers in nearly alphabetical order these topics: Cognitive Biology, Computer Science, Economics, Linguistics, Psychology, Philosophy, and Neuroscience. Linked through that list of topics, upon its selection the Cognitive Biology page offers a selection of reviews and articles with biological content ranging from cognitive ethology through evolutionary epistemology; cognition and art; evo-devo and cognitive science; animal learning; genes and cognition; cognition and animal welfare; etc.

A different application of the cognitive biology category is manifest in the 2009 publication of papers presented at a three-day interdisciplinary workshop on “The New Cognitive Sciences” held at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research in 2006. The papers were listed under four headings, each representing a different domain of requisite cognitive ability: (i) space, (ii) qualities and objects, (iii) numbers and probabilities, and (iv) social entities. The workshop papers examined topics ranging from “Animals as Natural Geometers” and “Color Generalization by Birds” through “Evolutionary Biology of Limited Attention” and “A comparative Perspective on the Origin of Numerical Thinking” as well as “Neuroethology of Attention in Primates” and ten more with less colorful titles. “[O]n the last day of the workshop the participants agreed [that] the title ‘Cognitive Biology’ sounded like a potential candidate to capture the merging of the cognitive and the life sciences that the workshop aimed at representing.” Thus the publication of Tommasi, et al. (2009), Cognitive Biology: Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives on Mind, Brain and Behavior.

A final example of categorical use comes from an author’s introduction to his 2011 publication on the subject, Cognitive Biology: Dealing with Information from Bacteria to Minds. After discussing the differences between the cognitive and biological sciences, as well as the value of one to the other, the author concludes: “Thus, the object of this book should be considered as an attempt at building a new discipline, that of cognitive biology, which endeavors to bridge these two domains.” There follows a detailed methodology illustrated by examples in biology anchored by concepts from cybernetics (e.g., self-regulatory systems) and quantum information theory (regarding probabilistic changes of state) with an invitation "to consider system theory together with information theory as the formal tools that may ground biology and cognition as traditional mathematics grounds physics.”