From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Membership and participation

|

|

For two articles dealing with the membership of and participation in the General Assembly, see:

|

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; French: Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations

(UN), serving as the main deliberative, policy-making, and

representative organ of the UN. Its powers, composition, functions, and

procedures are set out in Chapter IV of the United Nations Charter. The UNGA is responsible for the UN budget, appointing the non-permanent members to the Security Council, appointing the Secretary-General of the United Nations, receiving reports from other parts of the UN system, and making recommendations through resolutions. It also establishes numerous subsidiary organs to advance or assist in its broad mandate. The UNGA is the only UN organ wherein all member states have equal representation.

The General Assembly meets under its president or the UN secretary-general in annual sessions at UN headquarters

in New York City; the main part of these meetings generally run from

September to part of January until all issues are addressed (which is

often before the next session starts). It can also reconvene for special and emergency special sessions. The first session was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of the 51 founding nations.

Voting in the General Assembly on certain important

questions—namely recommendations on peace and security; budgetary

concerns; and the election, admission, suspension or expulsion of

members—is by a two-thirds majority of those present and voting. Other questions are decided by a simple majority.

Each member country has one vote. Apart from the approval of budgetary

matters, including the adoption of a scale of assessment, Assembly

resolutions are not binding on the members. The Assembly may make

recommendations on any matters within the scope of the UN, except

matters of peace and security under the Security Council consideration.

During the 1980s, the Assembly became a forum for "North-South

dialogue" between industrialized nations and developing countries on a

range of international issues. These issues came to the fore because of

the phenomenal growth and changing makeup of the UN membership. In 1945,

the UN had 51 members, which by the 21st century nearly quadrupled to

193, of which more than two-thirds are developing.

Because of their numbers, developing countries are often able to

determine the agenda of the Assembly (using coordinating groups like the

G77),

the character of its debates, and the nature of its decisions. For many

developing countries, the UN is the source of much of their diplomatic

influence and the principal outlet for their foreign relations

initiatives.

Although the resolutions passed by the General Assembly do not

have the binding forces over the member nations (apart from budgetary

measures), pursuant to its Uniting for Peace

resolution of November 1950 (resolution 377 (V)), the Assembly may also

take action if the Security Council fails to act, owing to the negative

vote of a permanent member,

in a case where there appears to be a threat to the peace, breach of

the peace or act of aggression. The Assembly can consider the matter

immediately with a view to making recommendations to Members for

collective measures to maintain or restore international peace and

security.

History

Methodist Central Hall, London, the location of the first meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in 1946.

The first session of the UN General Assembly was convened on 10 January 1946 in the Methodist Central Hall in London and included representatives of 51 nations. The next few annual sessions were held in different cities: the second session in New York City, and the third in Paris. It moved to the permanent Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City at the start of its seventh regular annual session, on 14 October 1952. In December 1988, in order to hear Yasser Arafat, the General Assembly organized its 29th session in the Palace of Nations, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Membership

All 193 members of the United Nations are members of the General

Assembly, with the addition of Holy See and Palestine as observer

states. Further, the United Nations General Assembly may grant observer status

to an international organization or entity, which entitles the entity

to participate in the work of the United Nations General Assembly,

though with limitations.

Agenda

The

agenda for each session is planned up to seven months in advance and

begins with the release of a preliminary list of items to be included in

the provisional agenda.

This is refined into a provisional agenda 60 days before the opening of

the session. After the session begins, the final agenda is adopted in a

plenary meeting which allocates the work to the various Main

Committees, who later submit reports back to the Assembly for adoption

by consensus or by vote.

Items on the agenda are numbered. Regular plenary sessions of the

General Assembly in recent years have initially been scheduled to be

held over the course of just three months; however, additional workloads

have extended these sessions until just short of the next session. The

routinely scheduled portions of the sessions normally commence on "the

Tuesday of the third week in September, counting from the first week

that contains at least one working day", per the UN Rules of Procedure. The last two of these Regular sessions were routinely scheduled to recess exactly three months afterwards in early December, but were resumed in January and extended until just before the beginning of the following sessions.

Resolutions

Russian President

Dmitry Medvedev addresses the 64th session of the UN General Assembly on 24 September 2009

The General Assembly votes on many resolutions brought forth by

sponsoring states. These are generally statements symbolizing the sense

of the international community about an array of world issues.

Most General Assembly resolutions are not enforceable as a legal or

practical matter, because the General Assembly lacks enforcement powers

with respect to most issues. The General Assembly has authority to make final decisions in some areas such as the United Nations budget.

The General Assembly can also refer an issue to the Security Council to put in place a binding resolution.

Resolution numbering scheme

From

the First to the Thirtieth General Assembly sessions, all General

Assembly resolutions were numbered consecutively, with the resolution

number followed by the session number in Roman numbers (for example, Resolution 1514 (XV),

which was the 1514th numbered resolution adopted by the Assembly, and

was adopted at the Fifteenth Regular Session (1960)). Beginning in the

Thirty-First Session, resolutions are numbered by individual session

(for example Resolution 41/10 represents the 10th resolution adopted at

the Forty-First Session).

Budget

The

General Assembly also approves the budget of the United Nations and

decides how much money each member state must pay to run the

organization.

The Charter of the United Nations gives responsibility for

approving the budget to the General Assembly (Chapter IV, Article 17)

and for preparing the budget to the Secretary-General, as "chief

administrative officer" (Chapter XV, Article 97). The Charter also

addresses the non-payment of assessed contributions (Chapter IV, Article

19).

The planning, programming, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation cycle of

the United Nations has evolved over the years; major resolutions on the

process include General Assembly resolutions: 41/213 of 19 December

1986, 42/211 of 21 December 1987, and 45/248 of 21 December 1990.

The budget covers the costs of United Nations programmes in areas

such as political affairs, international justice and law, international

cooperation for development, public information, human rights, and

humanitarian affairs.

The main source of funds for the regular budget is the

contributions of member states. The scale of assessments is based on the

capacity of countries to pay. This is determined by considering their

relative shares of total gross national product, adjusted to take into

account a number of factors, including their per capita incomes.

In addition to the regular budget, member states are assessed for

the costs of the international tribunals and, in accordance with a

modified version of the basic scale, for the costs of peacekeeping

operations.

Elections

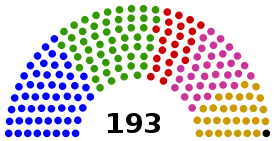

Division of the General Assembly by membership in the five United Nations Regional Groups:

The Group of African States (54)

The Group of Asia-Pacific States (54)

The Group of Eastern European States (23)

The Group of Latin American and Caribbean States (33)

The Group of Western European and Other States (28)

No group

The General Assembly is entrusted in the United Nations Charter with

electing members to various organs within the United Nations system. The

procedure for these elections can be found in Section 15 of the Rules

of Procedure for the General Assembly. The most important elections for

the General Assembly include those for the upcoming President of the General Assembly, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, the Human Rights Council and the International Court of Justice. Most elections are held annually, with the exception of the election of judges to the ICJ, which happens triennially.

The Assembly annually elects five non-permanent members of the

Security Council for two-year terms, 18 members of the Economic and

Social Council for three-year terms and 14–18 members of the Human

Rights Council for three-year terms. It also elects the leadership of

the next General Assembly session, i.e. the next President of the

General Assembly, the 21 Vice-Presidents and the bureaux of the six main

committees.

Elections to the International Court of Justice take place every

three years in order to ensure continuity within the court. In these

elections, five judges are elected for nine-year terms. These elections

are held jointly with the Security Council, with candidates needing to

receive an absolute majority of the votes in both bodies.

The Assembly also, in conjunction with the Security Council, selects the next Secretary-General

of the United Nations. The main part of these elections are held in the

Security Council, with the General Assembly simply appointing the

candidate that receives the Council's nomination.

Regional groups

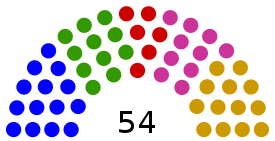

Division of seats of the Economic and Social Council based on regional grouping:

African States (14)

Asia-Pacific States (11)

Eastern European States (6)

Latin American and Caribbean States (10)

Western European and Other States (13)

The United Nations Regional Groups

were created in order to facilitate the equitable geographical

distribution of seats among the Member States in different United

Nations bodies. Resolution 33/138 of the General Assembly states that

"the composition of the various organs of the United Nations should be

so constituted as to ensure their representative character." Thus,

member States of the United Nations are informally divided into five

regions, with most bodies in the United Nations system having a specific

number of seats allocated for each regional group. Additionally, the

leadership of most bodies also rotates between the regional groups, such

as the presidency of the General Assembly and the chairmanship of the

six main committees.

The regional groups work according to the consensus principle.

Candidates who are endorsed by them are, as a rule, elected by the

General Assembly in any subsequent elections.

Sessions

Regular sessions

The

General Assembly meets annually in a regular session that opens on the

third Tuesday of September, and runs until the following September.

Sessions are held at United Nations Headquarters in New York unless

changed by the General Assembly by a majority vote.

The regular session is split into two distinct periods, the main

and resumed parts of the session. During the main part of the session,

which runs from the opening of the session until Christmas break in

December, most of the work of the Assembly is done. This period is the

Assembly's most intense period of work and includes the general debate

and the bulk of the work of the Main Committees. The resumed part of the

session, however, which runs from January until the beginning of the

new session, includes most thematic debates, consultation processes led

by the President of the General Assembly, and working group meetings.

General debate

Brazilian President

Dilma Rousseff

delivers the opening speech at the 66th Session of the General Assembly

on 21 September 2011, marking the first time a woman opened a United

Nations session

The general debate of each new session of the General Assembly is

held the week following the official opening of the session, typically

the following Tuesday, and is held without interruption for nine working

days. The general debate is a high-level event, typically attended by

Member States' Heads of State or Government,

government ministers and United Nations delegates. At the general

debate, Member States are given the opportunity to raise attention to

topics or issues that they feel are important. In addition to the

general debate, there are also many other high-level thematic meetings,

summits and informal events held during general debate week.

The General debate is held in the General Assembly Hall at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Special sessions

Special sessions, or UNGASS, may be convened in three different ways,

at the request of the Security Council, at the request of a majority of

United Nations members States or by a single member, as long as a

majority concurs. Special sessions typically cover one single topic and

end with the adoption of one or two outcome documents, such as a

political declaration, action plan or strategy to combat said topic.

They are also typically high-level events with participation from heads

of state and government, as well as by government ministers. There have

been 30 special sessions in the history of the United Nations.

Emergency special sessions

In the event that the Security Council is unable, usually due to

disagreement among the permanent members, to come to a decision on a

threat to international peace and security, the General Assembly may

call an emergency special session in order to make appropriate

recommendations to Members States for collective measures. This power

was given to the Assembly in Resolution 377(V) of 3 November 1950.

Emergency special sessions can be called by the Security Council,

if supported by at least seven members, or by a majority of Member

States of the United Nations. If enough votes are had, the Assembly must

meet within 24 hours, with Members being notified at least twelve hours

before the opening of the session. There have been 10 emergency special

sessions in the history of the United Nations.

Subsidiary organs

The United Nations General Assembly building

The General Assembly subsidiary organs are divided into five

categories: committees (30 total, six main), commissions (six), boards

(seven), councils (four) and panels (one), working groups, and "other".

Committees

Main committees

The main committees are ordinally numbered, 1–6:

The roles of many of the main committees have changed over time.

Until the late 1970s, the First Committee was the Political and Security

Committee (POLISEC) and there was also a sufficient number of

additional "political" matters that an additional, unnumbered main

committee, called the Special Political Committee, also sat. The Fourth

Committee formerly handled Trusteeship and Decolonization matters. With

the decreasing number of such matters to be addressed as the trust territories attained independence and the decolonization movement progressed, the functions of the Special Political Committee were merged into the Fourth Committee during the 1990s.

Each main committee consists of all the members of the General Assembly. Each elects a chairman, three vice chairmen, and a rapporteur at the outset of each regular General Assembly session.

Other committees

These are not numbered. According to the General Assembly website, the most important are:

- Credentials Committee – This committee is charged with ensuring that the diplomatic credentials

of all UN representatives are in order. The Credentials Committee

consists of nine Member States elected early in each regular General

Assembly session.

- General Committee –

This is a supervisory committee entrusted with ensuring that the whole

meeting of the Assembly goes smoothly. The General Committee consists of

the president and vice presidents of the current General Assembly

session and the chairman of each of the six Main Committees.

Other committees of the General Assembly are enumerated.

Commissions

There are six commissions:

Despite its name, the former United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was actually a subsidiary body of ECOSOC.

Boards

There are seven boards which are categorized into two groups:

a) Executive Boards and b) Boards

Executive Boards

- Executive Board of the United Nations Children's Fund, established by GA Resolution 57 (I) and 48/162

- Executive Board of the United Nations Development Programme and of

the United Nations Population Fund, established by GA Resolution 2029

(XX) and 48/162

- Executive Board of the World Food Programme, established by GA Resolution 50/8

Boards

- Board of Auditors, established by GA Resolution 74 (I)

- Trade and Development Board, established by GA Resolution 1995 (XIX)

- United Nations Joint Staff Pension Board, established by GA Resolution 248 (III)

- Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters, established by GA Resolution 37/99 K

Councils and panels

The newest council is the United Nations Human Rights Council, which replaced the aforementioned UNCHR in March 2006.

There are a total of four councils and one panel.

Working Groups and other

There is a varied group of working groups and other subsidiary bodies.

Seating

Countries

are seated alphabetically in the General Assembly according to English

translations of the countries' names. The country which occupies the

front-most left position is determined annually by the Secretary-General

via ballot draw. The remaining countries follow alphabetically after

it.

Reform and UNPA

On 21 March 2005, Secretary-General Kofi Annan presented a report, In Larger Freedom,

that criticized the General Assembly for focusing so much on consensus

that it was passing watered-down resolutions reflecting "the lowest

common denominator of widely different opinions".

He also criticized the Assembly for trying to address too broad an

agenda, instead of focusing on "the major substantive issues of the day,

such as international migration

and the long-debated comprehensive convention on terrorism". Annan

recommended streamlining the General Assembly's agenda, committee

structure, and procedures; strengthening the role and authority of its president; enhancing the role of civil society; and establishing a mechanism to review the decisions of its committees, in order to minimize unfunded mandates and micromanagement of the United Nations Secretariat.

Annan reminded UN members of their responsibility to implement reforms,

if they expect to realize improvements in UN effectiveness.

The reform proposals were not taken up by the United Nations

World Summit in September 2005. Instead, the Summit solely affirmed the

central position of the General Assembly as the chief deliberative,

policymaking and representative organ of the United Nations, as well as

the advisory role of the Assembly in the process of standard-setting and

the codification of international law. The Summit also called for

strengthening the relationship between the General Assembly and the

other principal organs to ensure better coordination on topical issues

that required coordinated action by the United Nations, in accordance

with their respective mandates.

A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, or United Nations

People's Assembly (UNPA), is a proposed addition to the United Nations

System that eventually could allow for direct election of UN parliament

members by citizens all over the world.

In the General Debate of the 65th General Assembly, Jorge Valero, representing Venezuela,

said "The United Nations has exhausted its model and it is not simply a

matter of proceeding with reform, the twenty-first century demands deep

changes that are only possible with a rebuilding of this organisation."

He pointed to the futility of resolutions concerning the Cuban embargo and the Middle East conflict

as reasons for the UN model having failed. Venezuela also called for

the suspension of veto rights in the Security Council because it was a

"remnant of the Second World War [it] is incompatible with the principle

of sovereign equality of States".

Reform of the United Nations General Assembly includes proposals

to change the powers and composition of the U.N. General Assembly. This

could include, for example, tasking the Assembly with evaluating how

well member states implement UNGA resolutions, increasing the power of the assembly vis-à-vis the United Nations Security Council, or making debates more constructive and less repetitive.

Sidelines of the General Assembly

The

annual session of the United Nations General Assembly is accompanied by

independent meetings between world leaders, better known as meetings

taking place on the sidelines of the Assembly meeting. The

diplomatic congregation has also since evolved into a week attracting

wealthy and influential individuals from around the world to New York

City to address various agendas, ranging from humanitarian and

environmental to business and political.