Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or through biochemical analysis to measure specific protein output. In a medical setting, genetic testing can be used to diagnose or rule out suspected genetic disorders, predict risks for specific conditions, or gain information that can be used to customize medical treatments based on an individual's genetic makeup. Genetic testing can also be used to determine biological relatives, such as a child's parentage (genetic mother and father) through DNA paternity testing, or be used to broadly predict an individual's ancestry. Genetic testing of plants and animals can be used for similar reasons as in humans (e.g. to assess relatedness/ancestry or predict/diagnose genetic disorders), to gain information used for selective breeding, or for efforts to boost genetic diversity in endangered populations.

The variety of genetic tests has expanded throughout the years. Early forms of genetic testing which began in the 1950s involved counting the number of chromosomes per cell. Deviations from the expected number of chromosomes (46 in humans) could lead to a diagnosis of certain genetic conditions such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) or monosomy X (Turner syndrome). In the 1970s, a method to stain specific regions of chromosomes, called chromosome banding, was developed that allowed more detailed analysis of chromosome structure and diagnosis of genetic disorders that involved large structural rearrangements. In addition to analyzing whole chromosomes (cytogenetics), genetic testing has expanded to include the fields of molecular genetics and genomics which can identify changes at the level of individual genes, parts of genes, or even single nucleotide "letters" of DNA sequence.

According to the National Institutes of Health, there are tests available for more than 2,000 genetic conditions, and one study estimated that as of 2017 there were more than 75,000 genetic tests on the market.

Types

Genetic testing is "the analysis of chromosomes (DNA), proteins, and certain metabolites in order to detect heritable disease-related genotypes, mutations, phenotypes, or karyotypes for clinical purposes." It can provide information about a person's genes and chromosomes throughout life.

There are a number of types of testing available, including:

- Cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) testing - a non-invasive (for the fetus) test. It is performed on a sample of venous blood from the mother, and can provide information about the fetus early in pregnancy. As of 2015 it is the most sensitive and specific screening test for Down syndrome.

- Newborn screening - used just after birth to identify genetic disorders that can be treated early in life. A blood sample is collected with a heel prick from the newborn 24–48 hours after birth and sent to the lab for analysis. In the United States, newborn screening procedure varies state by state, but all states by law test for at least 21 disorders. If abnormal results are obtained, it does not necessarily mean the child has the disorder. Diagnostic tests must follow the initial screening to confirm the disease. The routine testing of infants for certain disorders is the most widespread use of genetic testing—millions of babies are tested each year in the United States. All states currently test infants for phenylketonuria (a genetic disorder that causes mental illness if left untreated) and congenital hypothyroidism (a disorder of the thyroid gland). People with PKU do not have an enzyme needed to process the amino acid phenylalanine, which is responsible for normal growth in children and normal protein use throughout their lifetime. If there is a buildup of too much phenylalanine, brain tissue can be damaged, causing developmental delay. Newborn screening can detect the presence of PKU, allowing children to be placed on special diets to avoid the effects of the disorder.

- Diagnostic testing - used to diagnose or rule out a specific genetic or chromosomal condition. In many cases, genetic testing is used to confirm a diagnosis when a particular condition is suspected based on physical mutations and symptoms. Diagnostic testing can be performed at any time during a person's life, but is not available for all genes or all genetic conditions. The results of a diagnostic test can influence a person's choices about health care and the management of the disease. For example, people with a family history of polycystic kidney disease (PKD) who experience pain or tenderness in their abdomen, blood in their urine, frequent urination, pain in the sides, a urinary tract infection or kidney stones may decide to have their genes tested and the result could confirm the diagnosis of PKD.

- Carrier testing - used to identify people who carry one copy of a gene mutation that, when present in two copies, causes a genetic disorder. This type of testing is offered to individuals who have a family history of a genetic disorder and to people in ethnic groups with an increased risk of specific genetic conditions. If both parents are tested, the test can provide information about a couple's risk of having a child with a genetic condition like cystic fibrosis.

- Preimplantation genetic diagnosis - performed on human embryos prior to the implantation as part of an in vitro fertilization procedure. Pre-implantation testing is used when individuals try to conceive a child through in vitro fertilization. Eggs from the woman and sperm from the man are removed and fertilized outside the body to create multiple embryos. The embryos are individually screened for abnormalities, and the ones without abnormalities are implanted in the uterus.

- Prenatal diagnosis - used to detect changes in a fetus's genes or chromosomes before birth. This type of testing is offered to couples with an increased risk of having a baby with a genetic or chromosomal disorder. In some cases, prenatal testing can lessen a couple's uncertainty or help them decide whether to abort the pregnancy. It cannot identify all possible inherited disorders and birth defects, however. One method of performing a prenatal genetic test involves an amniocentesis, which removes a sample of fluid from the mother's amniotic sac 15 to 20 or more weeks into pregnancy. The fluid is then tested for chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome (Trisomy 21) and Trisomy 18, which can result in neonatal or fetal death. Test results can be retrieved within 7–14 days after the test is done. This method is 99.4% accurate at detecting and diagnosing fetal chromosome abnormalities. There is a slight risk of miscarriage with this test, about 1:400. Another method of prenatal testing is Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS). Chorionic villi are projections from the placenta that carry the same genetic makeup as the baby. During this method of prenatal testing, a sample of chorionic villi is removed from the placenta to be tested. This test is performed 10–13 weeks into pregnancy and results are ready 7–14 days after the test was done. Another test using blood taken from the fetal umbilical cord is percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling.

- Predictive and presymptomatic testing - used to detect gene mutations associated with disorders that appear after birth, often later in life. These tests can be helpful to people who have a family member with a genetic disorder, but who have no features of the disorder themselves at the time of testing. Predictive testing can identify mutations that increase a person's chances of developing disorders with a genetic basis, such as certain types of cancer. For example, an individual with a mutation in BRCA1 has a 65% cumulative risk of breast cancer. Hereditary breast cancer along with ovarian cancer syndrome are caused by gene alterations in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Major cancer types related to mutations in these genes are female breast cancer, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and male breast cancer. Li-Fraumeni syndrome is caused by a gene alteration on the gene TP53. Cancer types associated with a mutation on this gene include breast cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma (bone cancer), leukemia and brain tumors. In the Cowden syndrome there is a mutation on the PTEN gene, causing potential breast, thyroid or endometrial cancer. Presymptomatic testing can determine whether a person will develop a genetic disorder, such as hemochromatosis (an iron overload disorder), before any signs or symptoms appear. The results of predictive and presymptomatic testing can provide information about a person's risk of developing a specific disorder, help with making decisions about medical care and provide a better prognosis.

- Pharmacogenomics - determines the influence of genetic variation on drug response. When a person has a disease or health condition, pharmacogenomics can examine an individual's genetic makeup to determine what medicine and what dosage would be the safest and most beneficial to the patient. In the human population, there are approximately 11 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in people's genomes, making them the most common variations in the human genome. SNPs reveal information about an individual's response to certain drugs. This type of genetic testing can be used for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. A sample of the cancer tissue can be sent in for genetic analysis by a specialized lab. After analysis, information retrieved can identify mutations in the tumor which can be used to determine the best treatment option.

Non-diagnostic testing includes:

- Forensic testing - uses DNA sequences to identify an individual for legal purposes. Unlike the tests described above, forensic testing is not used to detect gene mutations associated with disease. This type of testing can identify crime or catastrophe victims, rule out or implicate a crime suspect, or establish biological relationships between people (for example, paternity).

- Paternity testing - uses special DNA markers to identify the same or similar inheritance patterns between related individuals. Based on the fact that we all inherit half of our DNA from the father, and half from the mother, DNA scientists test individuals to find the match of DNA sequences at some highly differential markers to draw the conclusion of relatedness.

- Genealogical DNA test - used to determine ancestry or ethnic heritage for genetic genealogy.

- Research testing - includes finding unknown genes, learning how genes work and advancing understanding of genetic conditions. The results of testing done as part of a research study are usually not available to patients or their healthcare providers.

Medical procedure

Genetic testing is often done as part of a genetic consultation and as of mid-2008 there were more than 1,200 clinically applicable genetic tests available. Once a person decides to proceed with genetic testing, a medical geneticist, genetic counselor, primary care doctor, or specialist can order the test after obtaining informed consent.

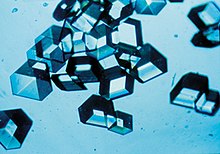

Genetic tests are performed on a sample of blood, hair, skin, amniotic fluid (the fluid that surrounds a fetus during pregnancy), or other tissue. For example, a medical procedure called a buccal smear uses a small brush or cotton swab to collect a sample of cells from the inside surface of the cheek. Alternatively, a small amount of saline mouthwash may be swished in the mouth to collect the cells. The sample is sent to a laboratory where technicians look for specific changes in chromosomes, DNA, or proteins, depending on the suspected disorders, often using DNA sequencing. The laboratory reports the test results in writing to a person's doctor or genetic counselor.

Routine newborn screening tests are done on a small blood sample obtained by pricking the baby's heel with a lancet.

Risks and limitations

The physical risks associated with most genetic tests are very small, particularly for those tests that require only a blood sample or buccal smear (a procedure that samples cells from the inside surface of the cheek). The procedures used for prenatal testing carry a small but non-negligible risk of losing the pregnancy (miscarriage) because they require a sample of amniotic fluid or tissue from around the fetus.

Many of the risks associated with genetic testing involve the emotional, social, or financial consequences of the test results. People may feel angry, depressed, anxious, or guilty about their results. The potential negative impact of genetic testing has led to an increasing recognition of a "right not to know". In some cases, genetic testing creates tension within a family because the results can reveal information about other family members in addition to the person who is tested. The possibility of genetic discrimination in employment or insurance is also a concern. Some individuals avoid genetic testing out of fear it will affect their ability to purchase insurance or find a job. Health insurers do not currently require applicants for coverage to undergo genetic testing, and when insurers encounter genetic information, it is subject to the same confidentiality protections as any other sensitive health information. In the United States, the use of genetic information is governed by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) (see discussion below in the section on government regulation).

Genetic testing can provide only limited information about an inherited condition. The test often can't determine if a person will show symptoms of a disorder, how severe the symptoms will be, or whether the disorder will progress over time. Another major limitation is the lack of treatment strategies for many genetic disorders once they are diagnosed.

Another limitation to genetic testing for a hereditary linked cancer, is the variants of unknown clinical significance. Because the human genome has over 22,000 genes, there are 3.5 million variants in the average person's genome. These variants of unknown clinical significance means there is a change in the DNA sequence, however the increase for cancer is unclear because it is unknown if the change affects the gene's function.

A genetics professional can explain in detail the benefits, risks, and limitations of a particular test. It is important that any person who is considering genetic testing understand and weigh these factors before making a decision.

Other risks include incidental findings—a discovery of some possible problem found while looking for something else. In 2013 the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) that certain genes always be included any time a genomic sequencing was done, and that labs should report the results.

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing (also called at-home genetic testing) is a type of genetic test that is accessible directly to the consumer without having to go through a health care professional. Usually, to obtain a genetic test, health care professionals such as physicians, nurse practitioners, or genetic counselors acquire their patient's permission and then order the desired test, which may or may not be covered by health insurance. DTC genetic tests, however, allow consumers to bypass this process and purchase DNA tests themselves. DTC genetic testing can entail primarily genealogical/ancestry-related information, health and trait-related information, or both.

There is a variety of DTC tests, ranging from tests for breast cancer alleles to mutations linked to cystic fibrosis. Possible benefits of DTC testing are the accessibility of tests to consumers, promotion of proactive healthcare, and the privacy of genetic information. Possible additional risks of DTC testing are the lack of governmental regulation, the potential misinterpretation of genetic information, issues related to testing minors, privacy of data, and downstream expenses for the public health care system. In the United States, most DTC genetic test kits are not reviewed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with the exception of a few tests offered by the company 23andMe. As of 2019, the tests that have received marketing authorization by the FDA include 23andMe's genetic health risk reports for select variants of BRCA1/BRCA2, pharmacogenetic reports that test for selected variants associated with metabolism of certain pharmaceutical compounds, a carrier screening test for Bloom syndrome, and genetic health risk reports for a handful of other medical conditions, such as celiac disease and late-onset Alzheimer's.

Controversy

DTC genetic testing has been controversial due to outspoken opposition within the medical community. Critics of DTC testing argue against the risks involved, the unregulated advertising and marketing claims, the potential reselling of genetic data to third parties, and the overall lack of governmental oversight.

DTC testing involves many of the same risks associated with any genetic test. One of the more obvious and dangerous of these is the possibility of misreading of test results. Without professional guidance, consumers can potentially misinterpret genetic information, causing them to be deluded about their personal health.

Some advertising for DTC genetic testing has been criticized as conveying an exaggerated and inaccurate message about the connection between genetic information and disease risk, utilizing emotions as a selling factor. An advertisement for a BRCA-predictive genetic test for breast cancer stated: “There is no stronger antidote for fear than information.” Apart from rare diseases that are directly caused by specific, single-gene mutation, diseases "have complicated, multiple genetic links that interact strongly with personal environment, lifestyle, and behavior."

Ancestry.com, a company providing DTC DNA tests for genealogy purposes, has reportedly allowed the warrantless search of their database by police investigating a murder. The warrantless search led to a search warrant to force the gathering of a DNA sample from a New Orleans filmmaker; however he turned out not to be a match for the suspected killer.

Governmental genetic testing

In Estonia

As part of its healthcare system, Estonia is offering all of its residents genome-wide genotyping. This will be translated into personalized reports for use in everyday medical practice via the national e-health portal.

The aim is to minimise health problems by warning participants most at risk of conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. It is also hoped that participants who are given early warnings will adopt healthier lifestyles or take preventative drugs.

Government regulation

In the United States

With regard to genetic testing and information in general, legislation in the United States called the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act prohibits group health plans and health insurers from denying coverage to a healthy individual or charging that person higher premiums based solely on a genetic predisposition to developing a disease in the future. The legislation also bars employers from using individuals’ genetic information when making hiring, firing, job placement, or promotion decisions. The legislation, the first of its kind in the United States, was passed by the United States Senate on April 24, 2008, on a vote of 95–0, and was signed into law by President George W. Bush on May 21, 2008. It went into effect on November 21, 2009.

In June 2013 the US Supreme Court issued two rulings on human genetics. The Court struck down patents on human genes, opening up competition in the field of genetic testing. The Supreme Court also ruled that police were allowed to collect DNA from people arrested for serious offenses.

In popular culture

Some possible future ethical problems of genetic testing were considered in the science fiction film Gattaca, the novel Next, and the science fiction anime series "Gundam Seed". Also, some films which include the topic of genetic testing include The Island, Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers, and the Resident Evil series.

Ethics

Pediatric genetic testing

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) have provided new guidelines for the ethical issue of pediatrics genetic testing and screening of children in the United States. Their guidelines state that performing pediatric genetic testing should be in the best interest of the child. In hypothetical situations for adults getting genetically tested 84-98% expressing interest in getting genetically tested for cancer predisposition. Though only half who are at risk of would get tested. AAP and ACMG recommend holding off on genetic testing for late-onset conditions until adulthood. Unless diagnosing genetic disorders during childhood and start early intervention can reduce morbidity or mortality. They also state that with parents or guardians permission testing for asymptomatic children who are at risk of childhood onset conditions are ideal reasons for pediatrics genetic testing. Testing for pharmacogenetics and newborn screening is found to be acceptable by AAP and ACMG guidelines. Histocompatibility testing guideline states that it's permissible for children of all ages to have tissue compatibility testing for immediate family members but only after the psychosocial, emotional and physical implications has been explored. With a donor advocate or similar mechanism should be in place to protect the minors from coercion and to safeguard the interest of said minor. Both AAP and ACMG discourage the use of direct-to-consumer and home kit genetic because of the accuracy, interpretation and oversight of test content. Guidelines also state that if parents or guardians should be encouraged to inform their child of the results from the genetic test if the minor is of appropriate age. If minor is of mature appropriate age and request results, the request should be honored. Though for ethical and legal reasons health care providers should be cautions in providing minors with predictive genetic testing without the involvement of parents or guardians. Within the guidelines AAP and ACMG state that health care provider have an obligation to inform parents or guardians on the implication of test results. To encourage patients and families to share information and even offer help in explain results to extend family or refer them to genetic counseling. AAP and ACMG state any type of predictive genetic testing for all types is best offer with genetic counseling being offer by Clinical genetics, genetic counselors or health care providers.

Israel

Israel uses DNA testing to determine if people are eligible for immigration. The policy where "many Jews from the Former Soviet Union (‘FSU’) are asked to provide DNA confirmation of their Jewish heritage in the form of paternity tests in order to immigrate as Jews and become citizens under Israel's Law of Return" has generated controversy.

Costs

The cost of genetic testing can range from under $100 to more than $2,000. This depends on the complexity of the test. The cost will increase if more than one test is necessary or if multiple family members are getting tested to obtain additional results. Costs can vary by state and some states cover part of the total cost.

From the date that a sample is taken, results may take weeks to months, depending upon the complexity and extent of the tests being performed. Results for prenatal testing are usually available more quickly because time is an important consideration in making decisions about a pregnancy. Prior to the testing, the doctor or genetic counselor who is requesting a particular test can provide specific information about the cost and time frame associated with that test.