| Year Without a Summer | |

|---|---|

1816 summer temperature anomaly compared to average temperatures from 1971 to 2000 | |

| Volcano | Mount Tambora |

| Start date | Eruption occurred on 10 April 1815 |

| Type | Ultra-Plinian |

| Location | Lesser Sunda Islands, Dutch East Indies (now Republic of Indonesia) |

| Impact | Caused a volcanic winter that dropped temperatures by 0.4–0.7 °C worldwide |

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by 0.4–0.7 °C (0.7–1 °F). Summer temperatures in Europe were the coldest on record between the years of 1766–2000. This resulted in major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere.

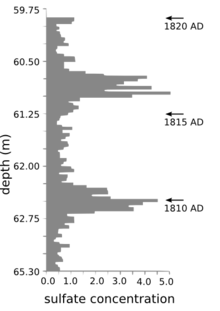

Evidence suggests that the anomaly was predominantly a volcanic winter event caused by the massive 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in April in the Dutch East Indies (known today as Indonesia). This eruption was the largest in at least 1,300 years (after the hypothesized eruption causing the extreme weather events of 535–536), and perhaps exacerbated by the 1814 eruption of Mayon in the Philippines.

Description

The Year Without a Summer was an agricultural disaster. Historian John D. Post has called this "the last great subsistence crisis in the Western world". The climatic aberrations of 1816 had greatest effect on most of New England, Atlantic Canada, and parts of western Europe.

Asia

In China there was a massive famine. Floods destroyed many remaining crops. The monsoon season was disrupted, resulting in overwhelming floods in the Yangtze Valley. In India, the delayed summer monsoon caused late torrential rains that aggravated the spread of cholera from a region near the Ganges in Bengal to as far as Moscow. Fort Shuangcheng, now in Heilongjiang, reported fields disrupted by frost and conscripts deserting as a result. Summer snowfall or otherwise mixed precipitation was reported in various locations in Jiangxi and Anhui, located at around 30°N. In Taiwan, which has a tropical climate, snow was reported in Hsinchu and Miaoli, and frost was reported in Changhua. In Japan, which was still exercising caution after the cold-weather-related Great Tenmei famine of 1782–1788, the cold damaged crops, but no crop failures were reported, and there were no adverse effects on population.

The aberrations are now generally thought to have occurred because of the April 5–15, 1815, Mount Tambora volcanic eruption on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. The eruption had a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) ranking of 7, a colossal event that ejected at least 100 km3 (24 cu mi) of material. It was the world's largest volcanic eruption during historic times comparable to Minoan eruption in the 2nd millennium B.C, the Hatepe eruption of Lake Taupo at around 180 A.D, the eruption of Paektu Mountain in 946 AD, and the 1257 eruption of Mount Samalas.

Other large volcanic eruptions (with VEIs at least 4) around this time were:

- 1808, the 1808 mystery eruption (VEI 6) in the southwestern Pacific Ocean

- 1812, La Soufrière on Saint Vincent in the Caribbean

- 1812, Awu in the Sangihe Islands, Dutch East Indies

- 1813, Suwanosejima in the Ryukyu Islands, Japan

- 1814, Mayon in the Philippines

These eruptions had built up a substantial amount of atmospheric dust. As is common after a massive volcanic eruption, temperatures fell worldwide because less sunlight passed through the stratosphere.

According to a 2012 analysis by Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature, the 1815 Tambora eruption caused a temporary drop in the Earth's average land temperature of about 1 °C. Smaller temperature drops were recorded from the 1812–1814 eruptions.

The Earth had already been in a centuries-long period of global cooling that started in the 14th century. Known today as the Little Ice Age, it had already caused considerable agricultural distress in Europe. The Little Ice Age's existing cooling was exacerbated by the eruption of Tambora, which occurred near the end of the Little Ice Age.

This period also occurred during the Dalton Minimum (a period of relatively low solar activity), specifically Solar Cycle 6, which ran from December 1810 to May 1823. May 1816 in particular had the lowest sunspot number (0.1) to date since record keeping on solar activity began. The lack of solar irradiance during this period was exacerbated by atmospheric opacity from volcanic dust.

Europe

As a result of the series of volcanic eruptions, crops had been poor for several years; the final blow came in 1815 with the eruption of Tambora. Europe, still recuperating from the Napoleonic Wars, suffered from food shortages. The impoverished especially suffered during this time. Low temperatures and heavy rains resulted in failed harvests in Britain and Ireland. Families in Wales traveled long distances begging for food. Famine was prevalent in north and southwest Ireland, following the failure of wheat, oat, and potato harvests. In Germany, the crisis was severe. Food prices rose sharply throughout Europe. With the cause of the problems unknown, hungry people demonstrated in front of grain markets and bakeries. Later riots, arson, and looting took place in many European cities. On some occasions, rioters carried flags reading "Bread or Blood". Though riots were common during times of hunger, the food riots of 1816 and 1817 were the highest levels of violence since the French Revolution. It was the worst famine of 19th-century mainland Europe.

Between 1816 and 1819 major typhus epidemics occurred in parts of Europe, including Ireland, Italy, Switzerland, and Scotland, precipitated by malnourishment and famine caused by the Year Without a Summer. More than 65,000 people died as the disease spread out of Ireland and to the rest of Britain.

The long-running Central England temperature record reported the 11th coldest year on records since 1659, as well as the 3rd coldest summer and the coldest July on record. Huge storms and abnormal rainfall with flooding of Europe's major rivers (including the Rhine) are attributed to the event, as is the August frost. As a result of volcanic ash in the atmosphere, Hungary experienced brown snow. Italy's northern and north-central region experienced something similar, with red snow falling throughout the year.

The effects were widespread and lasted beyond the winter. In western Switzerland, the summers of 1816 and 1817 were so cold that an ice dam formed below a tongue of the Giétro Glacier high in the Val de Bagnes. Despite engineer Ignaz Venetz's efforts to drain the growing lake, the ice dam collapsed catastrophically in June 1818, killing 40 people.

North America

In the spring and summer of 1816, a persistent "dry fog" was observed in parts of the eastern United States. The fog reddened and dimmed the sunlight, such that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Neither wind nor rainfall dispersed the "fog". It has been characterized as a "stratospheric sulfate aerosol veil".

The weather was not in itself a hardship for those accustomed to long winters. The real problem lay in the weather's effect on crops and thus on the supply of food and firewood. At higher elevations, where farming was problematic in good years, the cooler climate did not quite support agriculture. In May 1816, frost killed off most crops in the higher elevations of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont, as well as upstate New York. On June 6, snow fell in Albany, New York, and Dennysville, Maine. In Cape May, New Jersey, frost was reported five nights in a row in late June, causing extensive crop damage. New England also experienced major consequences from the eruption of Tambora. Though fruits and vegetable crops survived, corn was reported to have ripened so poorly that no more than a quarter of it was usable for food. This moldy and unripe harvest wasn't even fit for animal feed. The crop failures in New England, Canada, and parts of Europe also caused the price of many staples to rise sharply. In Canada, Quebec ran out of bread and milk and Nova Scotians found themselves boiling foraged herbs for sustenance.

Many commented on the phenomenon. Sarah Snell Bryant, of Cummington, Massachusetts, wrote in her diary, "Weather backward."

At the Church Family of Shakers near New Lebanon, New York, Nicholas Bennet wrote in May 1816, "all was froze" and the hills were "barren like winter". Temperatures went below freezing almost every day in May. The ground froze on June 9. On June 12, the Shakers had to replant crops destroyed by the cold. On July 7, it was so cold, everything had stopped growing. The Berkshire Hills had frost again on August 23, as did much of the upper northeast.

A Massachusetts historian summed up the disaster:

Severe frosts occurred every month; June 7th and 8th snow fell, and it was so cold that crops were cut down, even freezing the roots ... In the early Autumn when corn was in the milk it was so thoroughly frozen that it never ripened and was scarcely worth harvesting. Breadstuffs were scarce and prices high and the poorer class of people were often in straits for want of food. It must be remembered that the granaries of the great west had not then been opened to us by railroad communication, and people were obliged to rely upon their own resources or upon others in their immediate locality.

In July and August, lake and river ice was observed as far south as northwestern Pennsylvania. Frost was reported as far south as Virginia on August 20 and 21. Rapid, dramatic temperature swings were common, with temperatures sometimes reverting from normal or above-normal summer temperatures as high as 95 °F (35 °C) to near-freezing within hours. Thomas Jefferson, retired from the presidency and farming at Monticello, sustained crop failures that sent him further into debt. On September 13, a Virginia newspaper reported that corn crops would be one half to two-thirds short and lamented that "the cold as well as the drought has nipt the buds of hope". A Norfolk, Virginia newspaper reported:

It is now the middle of July, and we have not yet had what could properly be called summer. Easterly winds have prevailed for nearly three months past ... the sun during that time has generally been obscured and the sky overcast with clouds; the air has been damp and uncomfortable, and frequently so chilling as to render the fireside a desirable retreat.

Regional farmers did succeed in bringing some crops to maturity, but corn and other grain prices rose dramatically. The price of oats, for example, rose from 12¢ per bushel ($3.40/m3) in 1815 (equal to $1.7 today) to 92¢ per bushel ($26/m3) in 1816 ($14.03 today). Crop failures were aggravated by an inadequate transportation network: with few roads or navigable inland waterways and no railroads, it was expensive to import food.

Similar to Hungary and Italy, Maryland experienced brown, bluish, and yellow snowfall during April and May due to volcanic ash in the atmosphere.

Effects

High levels of tephra in the atmosphere caused a haze to hang over the sky for a few years after the eruption, as well as rich red hues in sunsets (common after volcanic eruptions). Paintings during the years before and after confirm that these striking reds were not present before Mt. Tambora's eruption. Similarly, these paintings depict moodier, darker scenes, even in the light of both the sun and the moon. Themes shifted away from hopeful and lighthearted afternoons, toward religion, industry, and a hint of despair. Many of the paintings during this time period were inspired by the Romantic style of painting and therefore were very realistic to the actual scenes that were being painted, effectively creating "snapshots" of the years prior to and after the eruption. Caspar David Friedrich's pieces Landscape with Rainbow (1810) and Two Men by the Sea (1817) are clear examples of this shift of mood. The colors in Landscape with Rainbow are bright and cheerful, the scene is brimming with optimism. Meanwhile, darkness, dread, and uncertainty penetrate Two Men by the Sea.

A 2007 study analyzing paintings created between the years 1500 and 1900 around the times of notable volcanic events found a correlation between the amount of red used in the painting and volcanic activity. High levels of tephra in the atmosphere led to unusually spectacular sunsets during this period, a feature celebrated in the paintings of J. M. W. Turner. This may have given rise to the yellow tinge predominant in his paintings such as Chichester Canal, circa 1828. Similar phenomena were observed after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, and on the West Coast of the United States following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines.

The lack of oats to feed horses may have inspired the German inventor Karl Drais to research new ways of horseless transportation, which led to the invention of the draisine or velocipede. This was the ancestor of the modern bicycle and a step toward mechanized personal transport.

The crop failures of the "Year without a Summer" may have helped shape the settling of the "American Heartland", as many thousands of people (particularly farm families who were wiped out by the event) left New England for western New York and the Northwest Territory in search of a more hospitable climate, richer soil, and better growing conditions. Indiana became a state in December 1816 and Illinois two years later. British historian Lawrence Goldman has suggested that this migration into the Burned-over district of New York was responsible for the centering of the anti-slavery movement in that region.

According to historian L. D. Stillwell, Vermont alone experienced a decrease in population of between 10,000 and 15,000, erasing seven previous years of population growth. Among those who left Vermont were the family of Joseph Smith, who moved from Norwich, Vermont (though he was born in Sharon, Vermont) to Palmyra, New York. This move precipitated the series of events that culminated in the publication of the Book of Mormon and the founding of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In June 1816, "incessant rainfall" during that "wet, ungenial summer" forced Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron and John William Polidori, and their friends to stay indoors at Villa Diodati overlooking Lake Geneva for much of their Swiss holiday. Inspired by a collection of German ghost stories they had read, Lord Byron proposed a contest to see who could write the scariest story, leading Shelley to write Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus and Lord Byron to write "A Fragment", which Polidori later used as inspiration for The Vampyre – a precursor to Dracula. These days inside Villa Diodati, remembered by Mary Shelley as happier times, were filled with tension, opium, and intellectual conversations. After listening intently to one of these conversations she woke with the image of Dr. Frankenstein kneeling over his monstrous creation, and thus she had the beginnings of her now famous story. In addition, Lord Byron was inspired to write the poem "Darkness", by a single day when "the fowls all went to roost at noon and candles had to be lit as at midnight". The imagery in the poem is starkly similar to the conditions of the Year Without a Summer:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day

Justus von Liebig, a chemist who had experienced the famine as a child in Darmstadt, later studied plant nutrition and introduced mineral fertilizers.

Comparable events

- Toba catastrophe 70,000 to 75,000 years ago

- The 1628–1626 BC climate disturbances, usually attributed to the Minoan eruption of Santorini

- The Hekla 3 eruption of about 1200 BC, contemporary with the historical Bronze Age collapse

- The Hatepe eruption (sometimes referred to as the Taupo eruption), around AD 180

- Extreme weather events of 535–536 have been linked to the effects of a volcanic eruption, possibly at Krakatoa, or Ilopango in El Salvador.

- The Heaven Lake eruption of Paektu Mountain between modern-day North Korea and the People's Republic of China, in 969 (± 20 years), is thought to have had a role in the downfall of Balhae.

- The 1257 Samalas eruption of Mount Rinjani on the island of Lombok in 1257

- An eruption of Kuwae, a Pacific volcano, has been implicated in events surrounding the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- An eruption of Huaynaputina, in Peru, caused 1601 to be the coldest year in the Northern Hemisphere for six centuries (see Russian famine of 1601–1603); 1601 consisted of a bitterly cold winter, a cold frosty nonexistent spring, and a cool cloudy wet summer.

- An eruption of Laki, in Iceland, was responsible for up to hundreds of thousands of fatalities throughout the Northern Hemisphere (over 25,000 in England alone), and one of the coldest winters ever recorded in North America, 1783–84; long-term consequences included poverty and famine that may have contributed to the French Revolution in 1789.

- The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa caused average Northern Hemisphere summer temperatures to fall by as much as 1.2 °C (2.2 °F). One of the wettest rainy seasons in recorded history followed in California during 1883–84.

- The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 led to odd weather patterns and temporary cooling in the United States, particularly in the Midwest and parts of the Northeast. Every month in 1992 except for January and February was colder-than-normal. More rain than normal fell across the West Coast of the United States, particularly California, during the 1991–92 and 1992–93 rainy seasons. The American Midwest experienced more rain and major flooding during the spring and summer of 1993. This may also have contributed to the historic "Storm of the Century" on the Atlantic Coast in March that same year.

In popular culture

American Murder Song, a musical project by Terrance Zdunich and Saar Hendelman, uses the "Year Without a Summer" as a backdrop for a collection of murder ballads.

In 1991 Pete Sutherland wrote a song about that terrible summer, titled "Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death." He based his song on an old poem in a book about Vermont folklore. He recorded the song with Karen Sutherland; Steve Gillette and Cindy Mangsen recorded it as well.

A song about the event entitled "1816, the Year Without a Summer" is the opening track on Rasputina's 2007 album Oh Perilous World.

The 2013 novel Without a Summer by Mary Robinette Kowal is set during the volcanic winter event, though the eruption itself is mentioned only in passing.

The 2019 anthology 1816: The Year Without Summer - Unredacted Cthulhu Almanac Vol I edited by Dickon Springate contains a series of stories inspired by the events of 1816.

A 2020 episode of Doctor Who entitled "The Haunting of Villa Diodati" attributes the cause of the abnormal weather to interference by one of the Cybermen.

The 2020 novel "The Year Without Summer" by Guinevere Glasfurd describes the eruption and impact on the lives of 6 characters around the world.

Famously the novel Frankenstein was composed during that summer when Mary Shelley and friends were on holiday near Lake Geneva and had to huddle indoors due to the weather.