| Attributes of God in Christianity |

|---|

|

The attributes of God are specific characteristics of God discussed in Christian theology. Christians are not monolithic in their understanding of God's attributes.

Classification

Many Reformed theologians distinguish between the communicable attributes (those that human beings can also have) and the incommunicable attributes (those that belong to God alone). Donald Macleod, however, argues that "All the suggested classifications are artificial and misleading, not least that which has been most favoured by Reformed theologians – the division into communicable and incommunicable attributes."

Many of these attributes only say what God is not – for example, saying he is immutable is saying that he does not change.

The attributes of God may be classified under two main categories:

- His infinite powers.

- His personality attributes, like holiness and love.

Millard Erickson calls these categories God's greatness and goodness respectively.

Sinclair Ferguson distinguishes "essential" divine attributes, which "have been expressed and experienced in its most intense and dynamic form among the three persons of the Trinity—when nothing else existed." In this way, the wrath of God is not an essential attribute because it had "no place in the inner communion among the three persons of the eternal Trinity." Ferguson notes that it is, however, a manifestation of God's eternal righteousness, which is an essential attribute.

Disputes

Various objections have been to certain attributes or combinations of attributes. The omnipotence paradox explores questions like, "Could God create a stone so heavy that even He could not lift it?" The problem of evil and the argument from poor design have been proposed to suggest that God cannot be omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient. Nevertheless, these criticisms have been robustly countered from the Scriptures by apologists from beginning from the early Church and throughout Church history. Some Christians overcome these objections by the notion of free will, in which God chooses not to control all that happens despite being able to because He considers freedom more important than an absence of suffering; by the notion that human experience is so limited that we are unable to fully perceive what a loving and fully powerful God "should" do at any one moment, and by the sheer fact that God, as transcendent creator of all logic and causality, is not bound by these restrictions Himself.

Another school of thought is that man is bound by his nature and his nature is always against God. In this understanding the sovereignty of God demands that a sinful humanity cannot do good apart from God, for to be reconciled to God would be an act of goodness outside of mans natural capabilities. In the act of faithfully believing the life, death and resurrection "for mans sin" by the shed blood of Jesus, the Son of God, till this is done goodness by God's standard is impossible. Generally instead of Free will a holder of this view will take on a more presuppositionalist approach while at the same time apply simple logic is to any attempt at question God's attributes/power/sovereignty. The presuppositionalist will proclaim the Gospel in the hopes God will grant the hearer a saving faith in Jesus despite this information and call to faith going completely against their natural inclinations. "Many are called, few are chosen" Matt 22:14, "all who where appointed to eternal life believed" Acts 13:48.

The Bible describes that every human inherently knows they need saving from their sin, from God's just judgment against them, but refuse because of their sin committed and sinful nature. God calls all to believe but will only save the elect by conforming their heart to faith in Jesus, though it goes against their anti-God nature. All who deny Jesus are given over to what they want, the elect "chosen" on the other hand are given a new heart to believe.

Enumeration

The Westminster Shorter Catechism's definition of God is an enumeration of his attributes: "God is a Spirit, infinite, eternal, and unchangeable in his being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth." This answer has been criticised, however, as having "nothing specifically Christian about it." The Westminster Larger Catechism adds certain attributes to this description, such as "all-sufficient," "incomprehensible," "every where present" and "knowing all things".

Aseity

The aseity of God means "God is so independent that he does not need us." It is based on Acts 17:25, where it says that God "is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything" (NIV). This is often related to God's self-existence and his self-sufficiency.

Eternity

The eternity of God concerns his existence beyond time. Drawing on verses such as Psalm 90:2, Wayne Grudem states that, "God has no beginning, end, or succession of moments in his own being, and he sees all time equally vividly, yet God sees events in time and acts in time." The expression "Alpha and Omega" also used as title of God in Book of Revelation. God's eternity may be seen as an aspect of his infinity, discussed below.

Goodness

The goodness of God means that "God is the final standard of good, and all that God is and does is worthy of approval." Romans 11:22 in the King James Version says "Behold therefore the goodness and severity of God". Many theologians consider the goodness of God as an overarching attribute - Louis Berkhof, for example, sees it as including kindness, love, grace, mercy and longsuffering. The idea that God is "all good" is called his omnibenevolence.

Critics of Christian conceptions of God as all-good, all-knowing, and all-powerful cite the presence of evil in the world as evidence that it is impossible for all three attributes to be true; this contradiction is known as the problem of evil. The Evil God Challenge is a thought experiment that explores whether the hypothesis that God might be evil has symmetrical consequences to a good God, and whether it is more likely that God is good, evil, or non-existent.

Graciousness

The graciousness of God is a key tenet of Christianity. In Exodus 34:5-6, it is part of the Name of God, "Yahweh, Yahweh, the compassionate and gracious God". The descriptive of God in this text is, in Jewish tradition, called the "Thirteen Attributes of Mercy".

The word "gracious" is not used often in the New Testament to describe God, although the noun "grace" is used more than 100 times. 1 Peter 2:2-3 in the King James Version says "the Lord is gracious", but the New International Version has "the Lord is good".

Holiness

The holiness of God is that he is separate from sin and incorruptible. Noting the refrain of "Holy, holy, holy" in Isaiah 6:3 and Revelation 4:8, R. C. Sproul points out that "only once in sacred Scripture is an attribute of God elevated to the third degree... The Bible never says that God is love, love, love."

Immanence

The immanence of God refers to him being in the world. It is thus contrasted with his transcendence, but Christian theologians usually emphasise that the two attributes are not contradictory. To hold to transcendence but not immanence is deism, while to hold to immanence but not transcendence is pantheism. According to Wayne Grudem, "the God of the Bible is no abstract deity removed from, and uninterested in his creation". Grudem goes on to say that the whole Bible "is the story of God's involvement with his creation", but highlights verses such as Acts 17:28, "in him we live and move and have our being".

Immutability

Immutability means God cannot change. James 1:17 refers to the "Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows" (NIV). Herman Bavinck notes that although the Bible talks about God changing a course of action, or becoming angry, these are the result of changes in the heart of God’s people (Numbers 14.) "Scripture testifies that in all these various relations and experiences, God remains ever the same." Millard Erickson calls this attribute God's constancy.

The immutability of God is being increasingly criticized by advocates of open theism, which argues that God is open to influence through the prayers, decisions, and actions of people. Prominent adherents of open theism include Clark Pinnock, John E. Sanders and Gregory Boyd.

Impassibility

The doctrine of the impassibility of God is a controversial one. It is usually defined as the inability of God to suffer, while recognising that Jesus, who is believed to be God, suffered in his human nature. The Westminster Confession of Faith says that God is "without body, parts, or passions". Although most Christians historically (Athanasius, Augustine, Aquinas, and Calvin being examples) take this to mean that God is "without emotions whether of sorrow, pain or grief", some people interpret this as meaning that God is free from all attitudes "which reflect instability or lack of control." Robert Reymond says that "it should be understood to mean that God has no bodily passions such as hunger or the human drive for sexual fulfillment."

D. A. Carson argues that "although Aristotle may exercise more than a little scarcely recognized influence upon those who uphold impassibility, at its best impassibility is trying to avoid a picture of God who is changeable, given over to mood swings, dependent on his creatures." In this way, impassibility is connected to the immutability of God, which says that God does not change, and to the aseity of God, which says that God does not need anything. Carson affirms that God is able to suffer, but argues that if he does so "it is because he chooses to suffer".

DA Carson, however, does not represent the historic use of the doctrine which affirms that God does not have emotions given that he is immutable and is incapable of change.

Impeccability

The impeccability of God is closely related to his holiness. It means that God is unable to sin, which is a stronger statement than merely saying that God does not sin. Hebrews 6:18 says that "it is impossible for God to lie". Robert Morey argues that God does not have the "absolute freedom" found in Greek philosophy. Whereas "the Greeks assumed the gods were 'free' to become demons if they so chose," the God of the Bible "is 'free' to act only in conformity to His nature."

Incomprehensibility

The incomprehensibility of God means that he is not able to be fully known. Isaiah 40:28 says "his understanding no one can fathom". Louis Berkhof states that "the consensus of opinion" through most of church history has been that God is the "Incomprehensible One". Berkhof, however, argues that, "in so far as God reveals Himself in His attributes, we also have some knowledge of His Divine Being, though even so our knowledge is subject to human limitations."

Incorporeality

The incorporeality or spirituality of God refers to him being a Spirit. This is derived from Jesus' statement in John 4:24, "God is Spirit." Robert Reymond suggests that it is the fact of his spiritual essence that underlies the second commandment, which prohibits every attempt to fashion an image of him."

Infinity

The infinity of God includes both his eternity and his immensity. Isaiah 40:28 says that "Yahweh is the everlasting God," while Solomon acknowledges in 1 Kings 8:27 that "the heavens, even the highest heaven, cannot contain you". Infinity permeates all other attributes of God: his goodness, love, power, etc. are all considered to be infinite.

The relationship between the infinity of God and mathematical infinity has often been discussed. Georg Cantor's work on infinity in mathematics was accused of undermining God's infinity, but Cantor argued that God's infinity is the Absolute Infinite, which transcends other forms of infinity.

Jealousy

Exodus 20:5-6, of the Decalogue says, "You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing love to a thousand generations of those who love me and keep my commandments" (NIV). J. I. Packer sees God's jealousy as "zeal to protect a love relationship or to avenge it when broken," thus making it "an aspect of his covenant love for his own people."

Love

1 John 4:8;16 says "God is Love." D. A. Carson speaks of the "difficult doctrine of the love of God," since "when informed Christians talk about the love of God they mean something very different from what is meant in the surrounding culture." Carson distinguishes between the love the Father has for the Son, God's general love for his creation, God's "salvific stance towards his fallen world," his "particular, effectual, selecting love toward his elect," and love that is conditioned on obedience.

The love of God is particularly emphasised by adherents of the social Trinitarian school of theology. Kevin Bidwell argues that this school, which includes Jürgen Moltmann and Miroslav Volf, "deliberately advocates self-giving love and freedom at the expense of Lordship and a whole array of other divine attributes."

Mission

While the mission of God is not traditionally included in this list, David Bosch has argued that "mission is not primarily an activity of the church, but an attribute of God." Christopher J. H. Wright argues for a biblical basis for Mission that goes beyond the Great Commission, and suggests that "missionary texts" may sparkle like gems, but that "simply laying out such gems on a string is not yet what one could call a missiological hermeneutic of the whole Bible itself."

Mystery

Many theologians see mystery as God’s primary attribute because he only reveals certain knowledge to the human race. Karl Barth said “God is ultimate mystery.” Karl Rahner views “God” as “mystery” and theology as “the ‘science’ of mystery.” Nikolai Berdyaev deems “inexplicable Mystery” as God’s “most profound definition.” Ian Ramsey defines God as “permanent mystery,”

Omnipotence

The omnipotence of God refers to Him being "all powerful". This is often conveyed with the phrase "Almighty", as in the Old Testament title "God Almighty" (the conventional translation of the Hebrew title El Shaddai) and the title "God the Father Almighty" in the Apostles' Creed.

Jesus says in Matthew 19:26, "with God all things are possible". C. S. Lewis clarifies this concept: "His Omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to him, but not nonsense. This is no limit to his power."

Omnipresence

The omnipresence of God refers to him being present everywhere. Berkhof distinguishes between God's immensity and his omnipresence, saying that the former "points to the fact that God transcends all space and is not subject to its limitations," emphasising his transcendence, while the latter denotes that God "fills every part of space with His entire Being," emphasising his immanence. In Psalm 139, David says, "If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there" (Psalm 139:8, NIV).

Omniscience

The omniscience of God refers to him being "all knowing". Berkhof regards the wisdom of God as a "particular aspect of his knowledge." Romans 16:27 speaks about the "only wise God".

An argument from free will proposes that omniscience and free will are incompatible, and that as a result either God does not exist or any concept of God that contains both of these elements is incorrect. An omniscient God has knowledge of the future, and thus what choices He will make. Because God's knowledge of the future is perfect, He cannot make a different choice, and therefore has no free will. Alternatively, a God with free will can make different choices based on knowledge of the future, and therefore God's knowledge of the future is imperfect or limited.

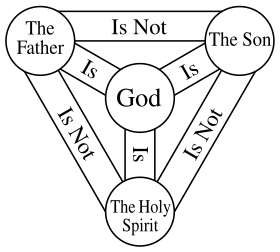

Oneness

The oneness, or unity of God refers to his being one and only. This means that Christianity is monotheistic, although the doctrine of the Trinity says that God is three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Athanasian Creed says "we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity."

The most notable biblical affirmation of the unity of God is found in Deuteronomy 6:4. The statement, known as the Shema Yisrael, after its first two words in Hebrew, says "Hear, O Israel: Yahweh our God, Yahweh is one." In the New Testament, Jesus upholds the oneness of God by quoting these words in Mark 12:29. The Apostle Paul also affirms the oneness of God in verses like Ephesians 4:6.

The oneness of God is also related to his simplicity.

Providence

While the providence of God usually refers to his activity in the world, it also implies his care for the universe, and is thus an attribute. Although the word is not used in the Bible to refer to God, the concept is found in verses such as Acts 17:25, which says that God "gives all men life and breath and everything else" (NIV).

A distinction is usually made between "general providence," which refers to God's continuous upholding the existence and natural order of the universe, and "special providence," which refers to God's extraordinary intervention in the life of people.

Righteousness

The righteousness of God may refer to his holiness, to his justice, or to his saving activity. A notable occurrence of the word is in Romans 1:17 - "for in the gospel the righteousness of God is revealed" (NIV). Martin Luther grew up believing that this referred to an attribute of God - namely, his distributive justice. Luther's change of mind and subsequent interpretation of the phrase as referring to the righteousness which God imputes to the believer was a major factor in the Protestant Reformation. More recently, however, scholars such as N. T. Wright have argued that the verse refers to an attribute of God after all - this time, his covenant faithfulness.

Simplicity

The simplicity of God means he is not partly this and partly that, but that whatever he is, he is so entirely. It is thus related to the unity of God. Grudem notes that this is a less common use of the word "simple" - that is, "not composed of parts". Grudem distinguishes between God's "unity of singularity" (in that God is one God) and his "unity of simplicity".

Sovereignty

The sovereignty of God is related to his omnipotence, providence, and kingship, yet it also encompasses his freedom, and is in keeping with his goodness, righteousness, holiness, and impeccability. It refers to God being in complete control as he directs all things — no person, organization, government or any other force can stop God from executing his purpose. This attribute has been particularly emphasized in Calvinism. The Calvinist writer A. W. Pink appeals to Isaiah 46:10 ("My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please") and argues, "Subject to none, influenced by none, absolutely independent; God does as He pleases, only as He pleases always as He pleases." Other Christian writers contend that the sovereign God desires to be influenced by prayer and that he "can and will change His mind when His people pray."

Transcendence

God's transcendence means that he is outside space and time, and therefore eternal and unable to be changed by forces within the universe. It is thus closely related to God's immutability, and is contrasted with his immanence. A significant verse which balances God's transcendence and his immanence is Isaiah 57:15:

For this is what the high and exalted One says — he who lives forever, whose name is holy: "I live in a high and holy place, but also with the one who is contrite and lowly in spirit, to revive the spirit of the lowly and to revive the heart of the contrite."

Trinity

Trinitarian traditions of Christianity propose the Trinity of God - three persons in one: Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. Support for the doctrine of the Trinity comes from several verses on the Bible and the New Testament's trinitarian formulae, such as the Great Commission of Matthew 28:19, "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit". Also, 1 John 5:7 (of the KJV) reads "...there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost, and these three are one", but this Comma Johanneum is almost universally rejected as a Latin corruption.

Nontrinitarian Christians do not hold that this is an attribute of God. Some believe that Jesus was only a prophet or perfected human, or that there is only one person of God with three aspects, or that there are two persons, or that they are three separate gods, or in various other doctrines.

Veracity

The veracity of God means his truth-telling. Titus 1:2 refers to "God, who does not lie." Among evangelicals, God's veracity is often regarded as the basis of the doctrine of biblical inerrancy. Greg Bahnsen says,

Only with an inerrant autograph can we avoid attributing error to the God of truth. An error in the original would be attributable to God Himself, because He, in the pages of Scripture, takes responsibility for the very words of the biblical authors. Errors in copies, however, are the sole responsibility of the scribes involved, in which case God’s veracity is not impugned.

Wrath

Moses praises the wrath of God in Exodus 15:7. Later in Deuteronomy 9, after the incident of The Golden Calf, Moses describes how: "I feared the furious anger of the LORD, which turned him against you, would drive him to destroy you. But again he listened to me." (9:19). In Psalm 69:24, the psalmist begs God to "consume" his enemies "with your burning anger".

In the New Testament, Jesus says in John 3:36, "Whoever believes in the Son has eternal life; whoever does not obey the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God remains on him."

Wayne Grudem suggests that "if God loves all that is right and good, and all that conforms to his moral character, then it should not be surprising that he would hate everything that is opposed to his moral character."