| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Environment WikiProject Ecology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A wildfire, bushfire, wild land fire or rural fire is an unplanned, unwanted, uncontrolled fire in an area of combustible vegetation starting in rural areas and urban areas.[1] Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire can also be classified more specifically as a forest fire, brush fire, bushfire (in Australia), desert fire, grass fire, hill fire, peat fire, prairie fire, vegetation fire, or veld fire.[2] Many organizations consider wildfire to mean an unplanned and unwanted fire,[3] while wild land-fire is a broader term that includes prescribed fire as well as wildland fire use (WFU; these are also called monitored response fires).[3][4]

Fossil charcoal indicates that wildfires began soon after the appearance of terrestrial plants 420 million years ago.[5] The occurrence of wildfires throughout the history of terrestrial life invites conjecture that fire must have had pronounced evolutionary effects on most ecosystems' flora and fauna.[6] Earth is an intrinsically flammable planet owing to its cover of carbon-rich vegetation, seasonally dry climates, atmospheric oxygen, and widespread lightning and volcanic ignitions.[6]

Wildfires can be characterized in terms of the cause of ignition, their physical properties, the combustible material present, and the effect of weather on the fire.[7] Wildfires can cause damage to property and human life, although naturally occurring wildfires [8] may have beneficial effects on native vegetation, animals, and ecosystems that have evolved with fire.[9][10] Wildfire behavior and severity result from a combination of factors such as available fuels, physical setting, and weather.[11][12][13][14] Analyses of historical meteorological data and national fire records in western North America show the primacy of climate in driving large regional fires via wet periods that create substantial fuels, or drought and warming that extend conducive fire weather.[15] Analyses of meteorological variables on wildfire risk have shown that relative humidity or precipitation can be used as good predictors for wildfire forecasting over the past several years.[16]

High-severity wildfire creates complex early seral forest habitat (also called "snag forest habitat"), which often has higher species richness and diversity than an unburned old forest. Many plant species depend on the effects of fire for growth and reproduction.[17] Wildfires in ecosystems where wildfire is uncommon or where non-native vegetation has encroached may have strongly negative ecological effects.[7]

Wildfires are among the most common forms of natural disaster in some regions, including Siberia, California, and Australia.[18][19][20] Areas with Mediterranean climates or in the taiga biome are particularly susceptible.

In the United States and other countries, aggressive wildfire suppression aimed at minimizing fire has contributed to accumulation of fuel loads, increasing the risk of large, catastrophic fires.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] In the United States especially, this wildfire suppression curtailed traditional land management methods practiced by Indigenous Peoples.[30][31][32] Modern forest management taking an ecological perspective engages in controlled burns to mitigate this risk and promote natural forest life cycles.

Causes

Natural

Leading natural causes of wildfires include:[33][34]

Human activity

In middle latitudes, the most common human causes of wildfires are equipment generating sparks (chainsaws, grinders, mowers, etc.), overhead power lines, and arson.[35][36][37][38][39][40] In the tropics, farmers often practice the slash-and-burn method of clearing fields during the dry season. When thousands of farmers do this simultaneously, much of a continent can appear from orbit to be one vast blaze.[41]

Coal seam fires burn in the thousands around the world, such as those in Burning Mountain, New South Wales; Centralia, Pennsylvania; and several coal-sustained fires in China. They can also flare up unexpectedly and ignite nearby flammable material.[42]

Spread

The spread of wildfires varies based on the flammable material present, its vertical arrangement and moisture content, and weather conditions.[43] Fuel arrangement and density is governed in part by topography, as land shape determines factors such as available sunlight and water for plant growth. Overall, fire types can be generally characterized by their fuels as follows:

- Ground fires are fed by subterranean roots, duff and other buried organic matter. This fuel type is especially susceptible to ignition due to spotting. Ground fires typically burn by smoldering, and can burn slowly for days to months, such as peat fires in Kalimantan and Eastern Sumatra, Indonesia, which resulted from a riceland creation project that unintentionally drained and dried the peat.[44][45][46]

- Crawling or surface fires are fueled by low-lying vegetation on the forest floor such as leaf and timber litter, debris, grass, and low-lying shrubbery.[47] This kind of fire often burns at a relatively lower temperature than crown fires (less than 400 °C (752 °F)) and may spread at slow rate, though steep slopes and wind can accelerate the rate of spread.[48]

- Ladder fires consume material between low-level vegetation and tree canopies, such as small trees, downed logs, and vines. Kudzu, Old World climbing fern, and other invasive plants that scale trees may also encourage ladder fires.[49]

- Crown, canopy, or aerial fires burn suspended material at the canopy level, such as tall trees, vines, and mosses. The ignition of a crown fire, termed crowning, is dependent on the density of the suspended material, canopy height, canopy continuity, sufficient surface and ladder fires, vegetation moisture content, and weather conditions during the blaze.[50] Stand-replacing fires lit by humans can spread into the Amazon rain forest, damaging ecosystems not particularly suited for heat or arid conditions.[51]

In monsoonal areas of north Australia, surface fires can spread, including across intended firebreaks, by burning or smoldering pieces of wood or burning tufts of grass carried intentionally by large flying birds accustomed to catch prey flushed out by wildfires. Species implicated are Black Kite (Milvus migrans), Whistling Kite (Haliastur sphenurus), and Brown Falcon (Falco berigora). Local Aborigines have known of this behavior for a long time, including in their mythology.[52]

Physical properties

Wildfires occur when all the necessary elements of a fire triforce come together in a susceptible area: an ignition source is brought into contact with a combustible material such as vegetation, that is subjected to enough heat and has an adequate supply of oxygen from the ambient air. A high moisture content usually prevents ignition and slows propagation, because higher temperatures are needed to evaporate any water in the material and heat the material to its fire point.[13][53] Dense forests usually provide more shade, resulting in lower ambient temperatures and greater humidity, and are therefore less susceptible to wildfires.[54] Less dense material such as grasses and leaves are easier to ignite because they contain less water than denser material such as branches and trunks.[55] Plants continuously lose water by evapotranspiration, but water loss is usually balanced by water absorbed from the soil, humidity, or rain.[56] When this balance is not maintained, plants dry out and are therefore more flammable, often a consequence of droughts.[57][58]

A wildfire front is the portion sustaining continuous flaming combustion, where unburned material meets active flames, or the smoldering transition between unburned and burned material.[59] As the front approaches, the fire heats both the surrounding air and woody material through convection and thermal radiation. First, wood is dried as water is vaporized at a temperature of 100 °C (212 °F). Next, the pyrolysis of wood at 230 °C (450 °F) releases flammable gases. Finally, wood can smolder at 380 °C (720 °F) or, when heated sufficiently, ignite at 590 °C (1,000 °F).[60][61] Even before the flames of a wildfire arrive at a particular location, heat transfer from the wildfire front warms the air to 800 °C (1,470 °F), which pre-heats and dries flammable materials, causing materials to ignite faster and allowing the fire to spread faster.[55][62] High-temperature and long-duration surface wildfires may encourage flashover or torching: the drying of tree canopies and their subsequent ignition from below.[63]

Wildfires have a rapid forward rate of spread (FROS) when burning through dense uninterrupted fuels.[64] They can move as fast as 10.8 kilometres per hour (6.7 mph) in forests and 22 kilometres per hour (14 mph) in grasslands.[65] Wildfires can advance tangential to the main front to form a flanking front, or burn in the opposite direction of the main front by backing.[66] They may also spread by jumping or spotting as winds and vertical convection columns carry firebrands (hot wood embers) and other burning materials through the air over roads, rivers, and other barriers that may otherwise act as firebreaks.[67][68] Torching and fires in tree canopies encourage spotting, and dry ground fuels around a wildfire are especially vulnerable to ignition from firebrands.[69] Spotting can create spot fires as hot embers and firebrands ignite fuels downwind from the fire. In Australian bushfires, spot fires are known to occur as far as 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the fire front.[70]

The incidence of large, uncontained wildfires in North America has increased in recent years, significantly impacting both urban and agriculturally-focused areas. The physical damage and health pressures left in the wake of uncontrolled fires has especially devastated farm and ranch operators in affected areas, prompting concern from the community of healthcare providers and advocates servicing this specialized occupational population.[71]

Especially large wildfires may affect air currents in their immediate vicinities by the stack effect: air rises as it is heated, and large wildfires create powerful updrafts that will draw in new, cooler air from surrounding areas in thermal columns.[72] Great vertical differences in temperature and humidity encourage pyrocumulus clouds, strong winds, and fire whirls with the force of tornadoes at speeds of more than 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph).[73][74][75] Rapid rates of spread, prolific crowning or spotting, the presence of fire whirls, and strong convection columns signify extreme conditions.[76]

The thermal heat from a wildfire can cause significant weathering of rocks and boulders, heat can rapidly expand a boulder and thermal shock can occur, which may cause an object's structure to fail.

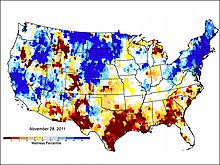

Effect of climate

Heat waves, droughts, climate variability such as El Niño, and regional weather patterns such as high-pressure ridges can increase the risk and alter the behavior of wildfires dramatically.[77][78][79] Years of precipitation followed by warm periods can encourage more widespread fires and longer fire seasons.[80] Since the mid-1980s, earlier snowmelt and associated warming has also been associated with an increase in length and severity of the wildfire season, or the most fire-prone time of the year,[81] in the Western United States.[82] Global warming may increase the intensity and frequency of droughts in many areas, creating more intense and frequent wildfires.[7] A 2019 study indicates that the increase in fire risk in California may be attributable to human-induced climate change.[83] A study of alluvial sediment deposits going back over 8,000 years found warmer climate periods experienced severe droughts and stand-replacing fires and concluded climate was such a powerful influence on wildfire that trying to recreate presettlement forest structure is likely impossible in a warmer future.[84]

Intensity also increases during daytime hours. Burn rates of smoldering logs are up to five times greater during the day due to lower humidity, increased temperatures, and increased wind speeds.[85] Sunlight warms the ground during the day which creates air currents that travel uphill. At night the land cools, creating air currents that travel downhill. Wildfires are fanned by these winds and often follow the air currents over hills and through valleys.[86] Fires in Europe occur frequently during the hours of 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m.[87] Wildfire suppression operations in the United States revolve around a 24-hour fire day that begins at 10:00 a.m. due to the predictable increase in intensity resulting from the daytime warmth.[88]

In the summer of 1974–1975 (southern hemisphere), Australia suffered its worst recorded wildfire, when 15% of Australia's land mass suffered "extensive fire damage".[89] Fires that summer burned up an estimated 117 million hectares (290 million acres; 1,170,000 square kilometres; 450,000 square miles).[90][91]

In 2019 extreme heat and dryness caused massive wildfires in Siberia, Alaska, Canary Islands, Australia, and in the Amazon rainforest. The fires in the latter were caused mainly by illegal logging. The smoke from the fires expanded on huge territory including major cities, dramatically reducing air quality.[92]

As of August 2020, the wildfires in the year were 13% worse than in 2019 due primarily to climate change and deforestation.[93] The Amazon rainforest's existence is threatened by fires, some of which may be criminal arson.[94][95][96][97] According to Mike Barrett, Executive Director of Science and Conservation at WWF-UK, if this rainforest is destroyed "we lose the fight against climate change. There will be no going back.”[93]

Emissions

Wildfires release large amounts of carbon dioxide, black and brown carbon particles, and ozone precursors such as volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the atmosphere.[98][99] These emissions affect radiation, clouds, and climate on regional and even global scales. Wildfires also emit substantial amounts of semi-volatile organic species that can partition from the gas phase to form secondary organic aerosol (SOA) over hours to days after emission. In addition, the formation of the other pollutants as the air is transported can lead to harmful exposures for populations in regions far away from the wildfires.[100] While direct emissions of harmful pollutants can affect first responders and local residents, wildfire smoke can also be transported over long distances and impact air quality across local, regional, and global scales.[101] Whether transported smoke plumes are relevant for surface air quality depends on where they exist in the atmosphere, which in turn depends on the initial injection height of the convective smoke plume into the atmosphere. Smoke that is injected above the planetary boundary layer (PBL) may be detectable from spaceborne satellites and play a role in altering the Earth's energy budget, but would not mix down to the surface where it would impact air quality and human health. Alternatively, smoke confined to a shallow PBL (through nighttime stable stratification of the atmosphere or terrain trapping) may become particularly concentrated and problematic for surface air quality. Wildfire intensity and smoke emissions are not constant throughout the fire lifetime and tend to follow a diurnal cycle that peaks in late afternoon and early evening, and which may be reasonably approximated using a monomodal or bimodal normal distribution.[102]

Over the past century, wildfires have accounted for 20-25% of global carbon emissions, the remainder from human activities.[103] Global carbon emissions from wildfires through August 2020 equaled the average annual emissions of the European Union.[93] In 2020, the carbon released by California's wildfires were significantly larger than the state's other carbon emissions.[104]

Ecology

Wildfire's occurrence throughout the history of terrestrial life invites conjecture that fire must have had pronounced evolutionary effects on most ecosystems' flora and fauna.[6] Wildfires are common in climates that are sufficiently moist to allow the growth of vegetation but feature extended dry, hot periods.[17] Such places include the vegetated areas of Australia and Southeast Asia, the veld in southern Africa, the fynbos in the Western Cape of South Africa, the forested areas of the United States and Canada, and the Mediterranean Basin.

High-severity wildfire creates complex early seral forest habitat (also called “snag forest habitat”), which often has higher species richness and diversity than unburned old forest.[9] Plant and animal species in most types of North American forests evolved with fire, and many of these species depend on wildfires, and particularly high-severity fires, to reproduce and grow. Fire helps to return nutrients from plant matter back to soil, the heat from fire is necessary to the germination of certain types of seeds, and the snags (dead trees) and early successional forests created by high-severity fire create habitat conditions that are beneficial to wildlife.[9] Early successional forests created by high-severity fire support some of the highest levels of native biodiversity found in temperate conifer forests.[10][105] Post-fire logging has no ecological benefits and many negative impacts; the same is often true for post-fire seeding.[106]

Although some ecosystems rely on naturally occurring fires to regulate growth, some ecosystems suffer from too much fire, such as the chaparral in southern California and lower-elevation deserts in the American Southwest. The increased fire frequency in these ordinarily fire-dependent areas has upset natural cycles, damaged native plant communities, and encouraged the growth of non-native weeds.[107][108][109][110] Invasive species, such as Lygodium microphyllum and Bromus tectorum, can grow rapidly in areas that were damaged by fires. Because they are highly flammable, they can increase the future risk of fire, creating a positive feedback loop that increases fire frequency and further alters native vegetation communities.[49][111]

In the Amazon Rainforest, drought, logging, cattle ranching practices, and slash-and-burn agriculture damage fire-resistant forests and promote the growth of flammable brush, creating a cycle that encourages more burning.[112] Fires in the rainforest threaten its collection of diverse species and produce large amounts of CO2.[113] Also, fires in the rainforest, along with drought and human involvement, could damage or destroy more than half of the Amazon rainforest by the year 2030.[114] Wildfires generate ash, reduce the availability of organic nutrients, and cause an increase in water runoff, eroding away other nutrients and creating flash flood conditions.[43][115] A 2003 wildfire in the North Yorkshire Moors burned off 2.5 square kilometers (600 acres) of heather and the underlying peat layers. Afterwards, wind erosion stripped the ash and the exposed soil, revealing archaeological remains dating back to 10,000 BC.[116] Wildfires can also have an effect on climate change, increasing the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere and inhibiting vegetation growth, which affects overall carbon uptake by plants.[117]

In tundra there is a natural pattern of accumulation of fuel and wildfire which varies depending on the nature of vegetation and terrain. Research in Alaska has shown fire-event return intervals, (FRIs) that typically vary from 150 to 200 years with dryer lowland areas burning more frequently than wetter upland areas.[118]

Plant adaptation

Plants in wildfire-prone ecosystems often survive through adaptations to their local fire regime. Such adaptations include physical protection against heat, increased growth after a fire event, and flammable materials that encourage fire and may eliminate competition. For example, plants of the genus Eucalyptus contain flammable oils that encourage fire and hard sclerophyll leaves to resist heat and drought, ensuring their dominance over less fire-tolerant species.[119][120] Dense bark, shedding lower branches, and high water content in external structures may also protect trees from rising temperatures.[17] Fire-resistant seeds and reserve shoots that sprout after a fire encourage species preservation, as embodied by pioneer species. Smoke, charred wood, and heat can stimulate the germination of seeds in a process called serotiny.[121] Exposure to smoke from burning plants promotes germination in other types of plants by inducing the production of the orange butenolide.[122]

Grasslands in Western Sabah, Malaysian pine forests, and Indonesian Casuarina forests are believed to have resulted from previous periods of fire.[123] Chamise deadwood litter is low in water content and flammable, and the shrub quickly sprouts after a fire.[17] Cape lilies lie dormant until flames brush away the covering and then blossom almost overnight.[124] Sequoia rely on periodic fires to reduce competition, release seeds from their cones, and clear the soil and canopy for new growth.[125] Caribbean Pine in Bahamian pineyards have adapted to and rely on low-intensity, surface fires for survival and growth. An optimum fire frequency for growth is every 3 to 10 years. Too frequent fires favor herbaceous plants, and infrequent fires favor species typical of Bahamian dry forests.[126]

Atmospheric effects

Most of the Earth's weather and air pollution resides in the troposphere, the part of the atmosphere that extends from the surface of the planet to a height of about 10 kilometers (6 mi). The vertical lift of a severe thunderstorm or pyrocumulonimbus can be enhanced in the area of a large wildfire, which can propel smoke, soot, and other particulate matter as high as the lower stratosphere.[127] Previously, prevailing scientific theory held that most particles in the stratosphere came from volcanoes, but smoke and other wildfire emissions have been detected from the lower stratosphere.[128] Pyrocumulus clouds can reach 6,100 meters (20,000 ft) over wildfires.[129] Satellite observation of smoke plumes from wildfires revealed that the plumes could be traced intact for distances exceeding 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi).[130] Computer-aided models such as CALPUFF may help predict the size and direction of wildfire-generated smoke plumes by using atmospheric dispersion modeling.[131]

Wildfires can affect local atmospheric pollution,[132] and release carbon in the form of carbon dioxide.[133] Wildfire emissions contain fine particulate matter which can cause cardiovascular and respiratory problems.[134] Increased fire byproducts in the troposphere can increase ozone concentration beyond safe levels.[135] Forest fires in Indonesia in 1997 were estimated to have released between 0.81 and 2.57 gigatonnes (0.89 and 2.83 billion short tons) of CO2 into the atmosphere, which is between 13%–40% of the annual global carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels.[136][137] In June and July of 2019, fires in the Arctic emitted more than 140 megatons of carbon dioxide, according to an analysis by CAMS. To put that into perspective this amounts to the same amount of carbon emitted by 36 million cars in a year. The recent wildfires and their massive CO2 emissions mean that it will be important to take them into consideration when implementing measures for reaching greenhouse gas reduction targets accorded with the Paris climate agreement.[138] Due to the complex oxidative chemistry occurring during the transport of wildfire smoke in the atmosphere,[139] the toxicity of emissions was indicated to increase over time.[140][141]

Atmospheric models suggest that these concentrations of sooty particles could increase absorption of incoming solar radiation during winter months by as much as 15%.[142] The Amazon is estimated to hold around 90 billion tons of carbon. As of 2019, earth's atmosphere has 415 parts per million of carbon, and the destruction of the Amazon would add about 38 parts per million.[143]

History

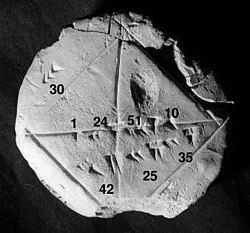

The first evidence of wildfires is rhyniophytoid plant fossils preserved as charcoal, discovered in the Welsh Borders, dating to the Silurian period (about 420 million years ago). Smoldering surface fires started to occur sometime before the Early Devonian period 405 million years ago. Low atmospheric oxygen during the Middle and Late Devonian was accompanied by a decrease in charcoal abundance.[144][145] Additional charcoal evidence suggests that fires continued through the Carboniferous period. Later, the overall increase of atmospheric oxygen from 13% in the Late Devonian to 30–31% by the Late Permian was accompanied by a more widespread distribution of wildfires.[146] Later, a decrease in wildfire-related charcoal deposits from the late Permian to the Triassic periods is explained by a decrease in oxygen levels.[147]

Wildfires during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic periods followed patterns similar to fires that occur in modern times. Surface fires driven by dry seasons[clarification needed] are evident in Devonian and Carboniferous progymnosperm forests. Lepidodendron forests dating to the Carboniferous period have charred peaks, evidence of crown fires. In Jurassic gymnosperm forests, there is evidence of high frequency, light surface fires.[147] The increase of fire activity in the late Tertiary[148] is possibly due to the increase of C4-type grasses. As these grasses shifted to more mesic habitats, their high flammability increased fire frequency, promoting grasslands over woodlands.[149] However, fire-prone habitats may have contributed to the prominence of trees such as those of the genera Eucalyptus, Pinus and Sequoia, which have thick bark to withstand fires and employ pyriscence.[150][151]

Human involvement

The human use of fire for agricultural and hunting purposes during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic ages altered the preexisting landscapes and fire regimes. Woodlands were gradually replaced by smaller vegetation that facilitated travel, hunting, seed-gathering and planting.[152] In recorded human history, minor allusions to wildfires were mentioned in the Bible and by classical writers such as Homer. However, while ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Roman writers were aware of fires, they were not very interested in the uncultivated lands where wildfires occurred.[153][154] Wildfires were used in battles throughout human history as early thermal weapons. From the Middle ages, accounts were written of occupational burning as well as customs and laws that governed the use of fire. In Germany, regular burning was documented in 1290 in the Odenwald and in 1344 in the Black Forest.[155] In the 14th century Sardinia, firebreaks were used for wildfire protection. In Spain during the 1550s, sheep husbandry was discouraged in certain provinces by Philip II due to the harmful effects of fires used in transhumance.[153][154] As early as the 17th century, Native Americans were observed using fire for many purposes including cultivation, signaling, and warfare. Scottish botanist David Douglas noted the native use of fire for tobacco cultivation, to encourage deer into smaller areas for hunting purposes, and to improve foraging for honey and grasshoppers. Charcoal found in sedimentary deposits off the Pacific coast of Central America suggests that more burning occurred in the 50 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas than after the colonization.[156] In the post-World War II Baltic region, socio-economic changes led more stringent air quality standards and bans on fires that eliminated traditional burning practices.[155] In the mid-19th century, explorers from HMS Beagle observed Australian Aborigines using fire for ground clearing, hunting, and regeneration of plant food in a method later named fire-stick farming.[157] Such careful use of fire has been employed for centuries in the lands protected by Kakadu National Park to encourage biodiversity.[158]

Wildfires typically occurred during periods of increased temperature and drought. An increase in fire-related debris flow in alluvial fans of northeastern Yellowstone National Park was linked to the period between AD 1050 and 1200, coinciding with the Medieval Warm Period.[159] However, human influence caused an increase in fire frequency. Dendrochronological fire scar data and charcoal layer data in Finland suggests that, while many fires occurred during severe drought conditions, an increase in the number of fires during 850 BC and 1660 AD can be attributed to human influence.[160] Charcoal evidence from the Americas suggested a general decrease in wildfires between 1 AD and 1750 compared to previous years. However, a period of increased fire frequency between 1750 and 1870 was suggested by charcoal data from North America and Asia, attributed to human population growth and influences such as land clearing practices. This period was followed by an overall decrease in burning in the 20th century, linked to the expansion of agriculture, increased livestock grazing, and fire prevention efforts.[161] A meta-analysis found that 17 times more land burned annually in California before 1800 compared to recent decades (1,800,000 hectares/year compared to 102,000 hectares/year).[162]

According to a paper published in Science, the number of natural and human-caused fires decreased by 24.3% between 1998 and 2015. Researchers explain this a transition from nomadism to settled lifestyle and intensification of agriculture that lead to a drop in the use of fire for land clearing.[163][164]

Increases of certain native tree species (i.e. conifers) in favor of others (i.e. leaf trees) also increases wildfire risk, especially if these trees are also planted in monocultures[165][166]

Some invasive species, moved in by humans (i.e., for the pulp and paper industry) have in some cases also increased the intensity of wildfires. Examples include species such as Eucalyptus in California[167][168] and gamba grass in Australia.

Prevention

Wildfire prevention refers to the preemptive methods aimed at reducing the risk of fires as well as lessening its severity and spread.[169] Prevention techniques aim to manage air quality, maintain ecological balances, protect resources,[111] and to affect future fires.[170] North American firefighting policies permit naturally caused fires to burn to maintain their ecological role, so long as the risks of escape into high-value areas are mitigated.[171] However, prevention policies must consider the role that humans play in wildfires, since, for example, 95% of forest fires in Europe are related to human involvement.[172] Sources of human-caused fire may include arson, accidental ignition, or the uncontrolled use of fire in land-clearing and agriculture such as the slash-and-burn farming in Southeast Asia.[173]

In 1937, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated a nationwide fire prevention campaign, highlighting the role of human carelessness in forest fires. Later posters of the program featured Uncle Sam, characters from the Disney movie Bambi, and the official mascot of the U.S. Forest Service, Smokey Bear.[174] Reducing human-caused ignitions may be the most effective means of reducing unwanted wildfire. Alteration of fuels is commonly undertaken when attempting to affect future fire risk and behavior.[43] Wildfire prevention programs around the world may employ techniques such as wildland fire use and prescribed or controlled burns.[175][176] Wildland fire use refers to any fire of natural causes that is monitored but allowed to burn. Controlled burns are fires ignited by government agencies under less dangerous weather conditions.[177]

Strategies for wildfire prevention, detection, control and suppression have varied over the years.[178] One common and inexpensive technique to reduce the risk of uncontrolled wildfires is controlled burning: intentionally igniting smaller less-intense fires to minimize the amount of flammable material available for a potential wildfire.[179][180] Vegetation may be burned periodically to limit the accumulation of plants and other debris that may serve as fuel, while also maintaining high species diversity.[181][182] Jan Van Wagtendonk, a biologist at the Yellowstone Field Station, claims that Wildfire itself is "the most effective treatment for reducing a fire's rate of spread, fireline intensity, flame length, and heat per unit of area."[183] While other people claim that controlled burns and a policy of allowing some wildfires to burn is the cheapest method and an ecologically appropriate policy for many forests, they tend not to take into account the economic value of resources that are consumed by the fire, especially merchantable timber.[106] Some studies conclude that while fuels may also be removed by logging, such thinning treatments may not be effective at reducing fire severity under extreme weather conditions.[184]

However, multi-agency studies conducted by the United States Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, and the School of Forestry and Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana, through strategic assessments of fire hazards and the potential effectiveness and costs of different hazard reduction treatments, clearly demonstrate that the most effective short- and long-term forest fire hazard reduction strategy and by far the most cost-effective method to yield long-term mitigation of forest fire risk is a comprehensive fuel reduction strategy that involves mechanical removal of overstocked trees through commercial logging and non-commercial thinning with no restrictions on the size of trees that are removed, resulting in considerably better long-term results compared to a non-commercial "thin below" operation or a commercial logging operation with diameter restrictions. Starting with a forest with a "high risk" of fire and a pre-treatment crowning index of 21, the "thin from below" practice of removing only very small trees resulted in an immediate crowning index of 43, with 29% of the post-treatment area rated "low risk" immediately and only 20% of the treatment area remaining "low risk" after 30 years, at a cost (net economic loss) of $439 per acre treated. Again starting with a forest at "high risk" of fire and a crowning index of 21, the strategy involving non-commercial thinning and commercial logging with size-restrictions resulted in an crowning index of 43 immediately post-treatment with 67% of the area considered "low risk" and 56% of the area remaining low risk after 30 years, at a cost (net economic loss) of $368 per acre treated. On the other hand, starting with a forest at "high risk" of fire and the same crowning index of 21, a comprehensive fire hazard reduction treatment strategy, without restrictions on size of trees removed, resulted in an immediate crowning index of 61 post-treatment with 69% of the treated area rated "low risk" immediately and 52% of the treated area remaining "low risk" after 30 years, with positive revenue (a net economic gain gain) of $8 per acre.[185][186]

Building codes in fire-prone areas typically require that structures be built of flame-resistant materials and a defensible space be maintained by clearing flammable materials within a prescribed distance from the structure.[187][188] Communities in the Philippines also maintain fire lines 5 to 10 meters (16 to 33 ft) wide between the forest and their village, and patrol these lines during summer months or seasons of dry weather.[189] Continued residential development in fire-prone areas and rebuilding structures destroyed by fires has been met with criticism.[190] The ecological benefits of fire are often overridden by the economic and safety benefits of protecting structures and human life.[191]

Detection

Fast and effective detection is a key factor in wildfire fighting.[192] Early detection efforts were focused on early response, accurate results in both daytime and nighttime, and the ability to prioritize fire danger.[193] Fire lookout towers were used in the United States in the early 20th century and fires were reported using telephones, carrier pigeons, and heliographs.[194] Aerial and land photography using instant cameras were used in the 1950s until infrared scanning was developed for fire detection in the 1960s. However, information analysis and delivery was often delayed by limitations in communication technology. Early satellite-derived fire analyses were hand-drawn on maps at a remote site and sent via overnight mail to the fire manager. During the Yellowstone fires of 1988, a data station was established in West Yellowstone, permitting the delivery of satellite-based fire information in approximately four hours.[193]

Currently, public hotlines, fire lookouts in towers, and ground and aerial patrols can be used as a means of early detection of forest fires. However, accurate human observation may be limited by operator fatigue, time of day, time of year, and geographic location. Electronic systems have gained popularity in recent years as a possible resolution to human operator error. A government report on a recent trial of three automated camera fire detection systems in Australia did, however, conclude "...detection by the camera systems was slower and less reliable than by a trained human observer". These systems may be semi- or fully automated and employ systems based on the risk area and degree of human presence, as suggested by GIS data analyses. An integrated approach of multiple systems can be used to merge satellite data, aerial imagery, and personnel position via Global Positioning System (GPS) into a collective whole for near-realtime use by wireless Incident Command Centers.[195]

A small, high risk area that features thick vegetation, a strong human presence, or is close to a critical urban area can be monitored using a local sensor network. Detection systems may include wireless sensor networks that act as automated weather systems: detecting temperature, humidity, and smoke.[196][197][198][199] These may be battery-powered, solar-powered, or tree-rechargeable: able to recharge their battery systems using the small electrical currents in plant material.[200] Larger, medium-risk areas can be monitored by scanning towers that incorporate fixed cameras and sensors to detect smoke or additional factors such as the infrared signature of carbon dioxide produced by fires. Additional capabilities such as night vision, brightness detection, and color change detection may also be incorporated into sensor arrays.[201][202][203]

Satellite and aerial monitoring through the use of planes, helicopter, or UAVs can provide a wider view and may be sufficient to monitor very large, low risk areas. These more sophisticated systems employ GPS and aircraft-mounted infrared or high-resolution visible cameras to identify and target wildfires.[204][205] Satellite-mounted sensors such as Envisat's Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer and European Remote-Sensing Satellite's Along-Track Scanning Radiometer can measure infrared radiation emitted by fires, identifying hot spots greater than 39 °C (102 °F).[206][207] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hazard Mapping System combines remote-sensing data from satellite sources such as Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), and Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) for detection of fire and smoke plume locations.[208][209] However, satellite detection is prone to offset errors, anywhere from 2 to 3 kilometers (1 to 2 mi) for MODIS and AVHRR data and up to 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) for GOES data.[210] Satellites in geostationary orbits may become disabled, and satellites in polar orbits are often limited by their short window of observation time. Cloud cover and image resolution may also limit the effectiveness of satellite imagery.[211] Global Forest Watch provides detailed daily updates on fire alerts. These are sourced from NASA FIRMS. “VIIRS Active Fires.”

In 2015 a new fire detection tool is in operation at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service (USFS) which uses data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite to detect smaller fires in more detail than previous space-based products. The high-resolution data is used with a computer model to predict how a fire will change direction based on weather and land conditions. The active fire detection product using data from Suomi NPP's Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) increases the resolution of fire observations to 1,230 feet (375 meters). Previous NASA satellite data products available since the early 2000s observed fires at 3,280 foot (1 kilometer) resolution. The data is one of the intelligence tools used by the USFS and Department of Interior agencies across the United States to guide resource allocation and strategic fire management decisions. The enhanced VIIRS fire product enables detection every 12 hours or less of much smaller fires and provides more detail and consistent tracking of fire lines during long-duration wildfires – capabilities critical for early warning systems and support of routine mapping of fire progression. Active fire locations are available to users within minutes from the satellite overpass through data processing facilities at the USFS Remote Sensing Applications Center, which uses technologies developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Direct Readout Laboratory in Greenbelt, Maryland. The model uses data on weather conditions and the land surrounding an active fire to predict 12–18 hours in advance whether a blaze will shift direction. The state of Colorado decided to incorporate the weather-fire model in its firefighting efforts beginning with the 2016 fire season.

In 2014, an international campaign was organized in South Africa's Kruger National Park to validate fire detection products including the new VIIRS active fire data. In advance of that campaign, the Meraka Institute of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research in Pretoria, South Africa, an early adopter of the VIIRS 375 m fire product, put it to use during several large wildfires in Kruger.

The demand for timely, high-quality fire information has increased in recent years. Wildfires in the United States burn an average of 7 million acres of land each year. For the last 10 years, the USFS and Department of Interior have spent a combined average of about $2–4 billion annually on wildfire suppression.

Suppression

Wildfire suppression depends on the technologies available in the area in which the wildfire occurs. In less developed nations the techniques used can be as simple as throwing sand or beating the fire with sticks or palm fronds.[212] In more advanced nations, the suppression methods vary due to increased technological capacity. Silver iodide can be used to encourage snow fall,[213] while fire retardants and water can be dropped onto fires by unmanned aerial vehicles, planes, and helicopters.[214][215] Complete fire suppression is no longer an expectation, but the majority of wildfires are often extinguished before they grow out of control. While more than 99% of the 10,000 new wildfires each year are contained, escaped wildfires under extreme weather conditions are difficult to suppress without a change in the weather. Wildfires in Canada and the US burn an average of 54,500 square kilometers (13,000,000 acres) per year.[216][217]

Above all, fighting wildfires can become deadly. A wildfire's burning front may also change direction unexpectedly and jump across fire breaks. Intense heat and smoke can lead to disorientation and loss of appreciation of the direction of the fire, which can make fires particularly dangerous. For example, during the 1949 Mann Gulch fire in Montana, United States, thirteen smokejumpers died when they lost their communication links, became disoriented, and were overtaken by the fire.[218] In the Australian February 2009 Victorian bushfires, at least 173 people died and over 2,029 homes and 3,500 structures were lost when they became engulfed by wildfire.[219]

Costs of wildfire suppression

In California, the U.S. Forest Service spends about $200 million per year to suppress 98% of wildfires and up to $1 billion to suppress the other 2% of fires that escape initial attack and become large.[220] While costs vary wildly from year to year, depending on the severity of each fire season, in the United States, local, state, federal and tribal agencies collectively spend tens of billions of dollars annually to suppress wildfires.

Wildland firefighting safety

Wildland fire fighters face several life-threatening hazards including heat stress, fatigue, smoke and dust, as well as the risk of other injuries such as burns, cuts and scrapes, animal bites, and even rhabdomyolysis.[221][222] Between 2000–2016, more than 350 wildland firefighters died on-duty.[223]

Especially in hot weather conditions, fires present the risk of heat stress, which can entail feeling heat, fatigue, weakness, vertigo, headache, or nausea. Heat stress can progress into heat strain, which entails physiological changes such as increased heart rate and core body temperature. This can lead to heat-related illnesses, such as heat rash, cramps, exhaustion or heat stroke. Various factors can contribute to the risks posed by heat stress, including strenuous work, personal risk factors such as age and fitness, dehydration, sleep deprivation, and burdensome personal protective equipment. Rest, cool water, and occasional breaks are crucial to mitigating the effects of heat stress.[221]

Smoke, ash, and debris can also pose serious respiratory hazards to wildland firefighters. The smoke and dust from wildfires can contain gases such as carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and formaldehyde, as well as particulates such as ash and silica. To reduce smoke exposure, wildfire fighting crews should, whenever possible, rotate firefighters through areas of heavy smoke, avoid downwind firefighting, use equipment rather than people in holding areas, and minimize mop-up. Camps and command posts should also be located upwind of wildfires. Protective clothing and equipment can also help minimize exposure to smoke and ash.[221]

Firefighters are also at risk of cardiac events including strokes and heart attacks. Firefighters should maintain good physical fitness. Fitness programs, medical screening and examination programs which include stress tests can minimize the risks of firefighting cardiac problems.[221] Other injury hazards wildland firefighters face include slips, trips, falls, burns, scrapes, and cuts from tools and equipment, being struck by trees, vehicles, or other objects, plant hazards such as thorns and poison ivy, snake and animal bites, vehicle crashes, electrocution from power lines or lightning storms, and unstable building structures.[221]

Firefighter safety zone guidelines

The U.S. Forest Service publishes guidelines for the minimum distance a firefighter should be from a flame.[224]

Fire retardants

Fire retardants are used to slow wildfires by inhibiting combustion. They are aqueous solutions of ammonium phosphates and ammonium sulfates, as well as thickening agents.[225] The decision to apply retardant depends on the magnitude, location and intensity of the wildfire. In certain instances, fire retardant may also be applied as a precautionary fire defense measure.[226]

Typical fire retardants contain the same agents as fertilizers. Fire retardants may also affect water quality through leaching, eutrophication, or misapplication. Fire retardant's effects on drinking water remain inconclusive.[227] Dilution factors, including water body size, rainfall, and water flow rates lessen the concentration and potency of fire retardant.[226] Wildfire debris (ash and sediment) clog rivers and reservoirs increasing the risk for floods and erosion that ultimately slow and/or damage water treatment systems.[227][228] There is continued concern of fire retardant effects on land, water, wildlife habitats, and watershed quality, additional research is needed. However, on the positive side, fire retardant (specifically its nitrogen and phosphorus components) has been shown to have a fertilizing effect on nutrient-deprived soils and thus creates a temporary increase in vegetation.[226]

The current USDA procedure maintains that the aerial application of fire retardant in the United States must clear waterways by a minimum of 300 feet in order to safeguard effects of retardant runoff. Aerial uses of fire retardants are required to avoid application near waterways and endangered species (plant and animal habitats). After any incident of fire retardant misapplication, the U.S. Forest Service requires reporting and assessment impacts be made in order to determine a mitigation, remediation, and/or restrictions on future retardant uses in that area.

Modeling

Wildfire modeling is concerned with numerical simulation of wildfires in order to comprehend and predict fire behavior.[229][230] Wildfire modeling aims to aid wildfire suppression, increase the safety of firefighters and the public, and minimize damage. Using computational science, wildfire modeling involves the statistical analysis of past fire events to predict spotting risks and front behavior. Various wildfire propagation models have been proposed in the past, including simple ellipses and egg- and fan-shaped models. Early attempts to determine wildfire behavior assumed terrain and vegetation uniformity. However, the exact behavior of a wildfire's front is dependent on a variety of factors, including wind speed and slope steepness. Modern growth models utilize a combination of past ellipsoidal descriptions and Huygens' Principle to simulate fire growth as a continuously expanding polygon.[231][232] Extreme value theory may also be used to predict the size of large wildfires. However, large fires that exceed suppression capabilities are often regarded as statistical outliers in standard analyses, even though fire policies are more influenced by large wildfires than by small fires.[233]

Human risk and exposure

Wildfire risk is the chance that a wildfire will start in or reach a particular area and the potential loss of human values if it does. Risk is dependent on variable factors such as human activities, weather patterns, availability of wildfire fuels, and the availability or lack of resources to suppress a fire.[234] Wildfires have continually been a threat to human populations. However, human-induced geographical and climatic changes are exposing populations more frequently to wildfires and increasing wildfire risk. It is speculated that the increase in wildfires arises from a century of wildfire suppression coupled with the rapid expansion of human developments into fire-prone wildlands.[235] Wildfires are naturally occurring events that aid in promoting forest health. Global warming and climate changes are causing an increase in temperatures and more droughts nationwide which contributes to an increase in wildfire risk.[236][237]

Airborne hazards

The most noticeable adverse effect of wildfires is the destruction of property. However, the release of hazardous chemicals from the burning of wildland fuels also significantly impacts health in humans.[238]

Wildfire smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide and water vapor. Other common smoke components present in lower concentrations are carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, acrolein, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, and benzene.[239] Small particulates suspended in air which come in solid form or in liquid droplets are also present in smoke. 80 -90% of wildfire smoke, by mass, is within the fine particle size class of 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller.[240]

Despite carbon dioxide's high concentration in smoke, it poses a low health risk due to its low toxicity. Rather, carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter, particularly 2.5 µm in diameter and smaller, have been identified as the major health threats.[239] Other chemicals are considered to be significant hazards but are found in concentrations that are too low to cause detectable health effects.

The degree of wildfire smoke exposure to an individual is dependent on the length, severity, duration, and proximity of the fire. People are exposed directly to smoke via the respiratory tract through inhalation of air pollutants. Indirectly, communities are exposed to wildfire debris that can contaminate soil and water supplies.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed the air quality index (AQI), a public resource that provides national air quality standard concentrations for common air pollutants. The public can use this index as a tool to determine their exposure to hazardous air pollutants based on visibility range.[241]

Fire ecologist Leda Kobziar found that wildfire smoke distributes microbial life on a global level.[242] She stated, "There are numerous allergens that we’ve found in the smoke. And so it may be that some people who are sensitive to smoke have that sensitivity, not only because of the particulate matter and the smoke but also because there are some biological organisms in it."[243]

Water pollution

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2021) |

It is well-known that debris and chemicals can runoff into waterways after wildfires making the drinking water sources unsafe. It is also known that wildfires can damage water treatment facilities making drinking water unsafe. Though, even when the water sources and treatment facilities are not damaged, drinking water inside buildings and in buried water distribution systems can be chemically contaminated. After the 2017 Tubbs Fire and 2018 Camp Fire in California hazardous waste levels of chemical contamination were found in multiple public drinking water systems impacted by wildfires.[244] Since 2018, additional wildfires that damaged drinking water distribution systems and plumbing in California and Oregon have caused chemical drinking water contamination.[245] Benzene is one of many chemicals that has been found in the drinking water systems and buildings after wildfires. Benzene can permeate certain plastic pipes and thus require long times to remove from the water distribution system infrastructure and building plumbing. Using a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency model,[246] researchers estimated more than286 days of constant flushing a single contaminated pipe 24 hours per day, 7 days a week were needed to reduce benzene below safe drinking wter limits.[247] Temperature increases caused by fires, including wildfires, can cause plastic water pipes to generate toxic chemicals [248] such as benzene into the water that they carry.[249]

Post-fire risks

After a wildfire, hazards remain. Residents returning to their homes may be at risk from falling fire-weakened trees. Humans and pets may also be harmed by falling into ash pits.

At-risk groups

Firefighters

Firefighters are at the greatest risk for acute and chronic health effects resulting from wildfire smoke exposure. Due to firefighters' occupational duties, they are frequently exposed to hazardous chemicals at close proximity for longer periods of time. A case study on the exposure of wildfire smoke among wildland firefighters shows that firefighters are exposed to significant levels of carbon monoxide and respiratory irritants above OSHA-permissible exposure limits (PEL) and ACGIH threshold limit values (TLV). 5–10% are overexposed. The study obtained exposure concentrations for one wildland firefighter over a 10-hour shift spent holding down a fireline. The firefighter was exposed to a wide range of carbon monoxide and respiratory irritants (a combination of particulate matter 3.5 µm and smaller, acrolein, and formaldehyde) levels. Carbon monoxide levels reached up to 160ppm and the TLV irritant index value reached a high of 10. In contrast, the OSHA PEL for carbon monoxide is 30ppm and for the TLV respiratory irritant index, the calculated threshold limit value is 1; any value above 1 exceeds exposure limits.[250]

Between 2001 and 2012, over 200 fatalities occurred among wildland firefighters. In addition to heat and chemical hazards, firefighters are also at risk for electrocution from power lines; injuries from equipment; slips, trips, and falls; injuries from vehicle rollovers; heat-related illness; insect bites and stings; stress; and rhabdomyolysis.[251]

Residents

Residents in communities surrounding wildfires are exposed to lower concentrations of chemicals, but they are at a greater risk for indirect exposure through water or soil contamination. Exposure to residents is greatly dependent on individual susceptibility. Vulnerable persons such as children (ages 0–4), the elderly (ages 65 and older), smokers, and pregnant women are at an increased risk due to their already compromised body systems, even when the exposures are present at low chemical concentrations and for relatively short exposure periods.[239] They are also at risk for future wildfires and may move away to areas they consider less risky.[252]

Wildfires affect large numbers of people in Western Canada and the United States. In California alone, more than 350,000 people live in towns and cities in "very high fire hazard severity zones".[253]

Direct risks to building residents in fire-prone areas can be moderated through design choices such as choosing fire-resistant vegetation, maintaining landscaping to avoid debris accumulation and to create firebreaks, and by selecting fire-retardant roofing materials. Potential compounding issues with poor air quality and heat during warmer months may be addressed with MERV 11 or higher outdoor air filtration in building ventilation systems, mechanical cooling, and a provision of a refuge area with additional air cleaning and cooling, if needed.[254]

Fetal exposure

Additionally, there is evidence of an increase in maternal stress, as documented by researchers M.H. O'Donnell and A.M. Behie, thus affecting birth outcomes. In Australia, studies show that male infants born with drastically higher average birth weights were born in mostly severely fire-affected areas. This is attributed to the fact that maternal signals directly affect fetal growth patterns.[255][256]

Asthma is one of the most common chronic disease among children in the United States affecting estimated 6.2 million children.[257] A recent area of research on asthma risk focuses specifically on the risk of air pollution during the gestational period. Several pathophysiology processes are involved are in this. In human's considerable airway development occurs during the 2nd and 3rd trimester and continue until 3 years of age.[258] It is hypothesized that exposure to these toxins during this period could have consequential effects as the epithelium of the lungs during this time could have increased permeability to toxins. Exposure to air pollution during parental and pre-natal stage could induce epigenetic changes which are responsible for the development of asthma.[259] Recent Meta-Analyses have found significant association between PM2.5, NO2 and development of asthma during childhood despite heterogeneity among studies.[260] Furthermore, maternal exposure to chronic stressor, which are most like to be present in distressed communities, which is also a relevant co relate of childhood asthma which may further help explain the early childhood exposure to air pollution, neighborhood poverty and childhood risk. Living in distressed neighborhood is not only linked to pollutant source location and exposure but can also be associated with degree of magnitude of chronic individual stress which can in turn alter the allostatic load of the maternal immune system leading to adverse outcomes in children, including increased susceptibility to air pollution and other hazards.[261]

Health effects

Wildfire smoke contains particulate matter that may have adverse effects upon the human respiratory system. Evidence of the health effects of wildfire smoke should be relayed to the public so that exposure may be limited. Evidence of health effects can also be used to influence policy to promote positive health outcomes.[262]

Inhalation of smoke from a wildfire can be a health hazard.[263] Wildfire smoke is composed of combustion products i.e. carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, water vapor, particulate matter, organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides and other compounds. The principal health concern is the inhalation of particulate matter and carbon monoxide.[264]

Particulate matter (PM) is a type of air pollution made up of particles of dust and liquid droplets. They are characterized into three categories based on the diameter of the particle: coarse PM, fine PM, and ultrafine PM. Coarse particles are between 2.5 micrometers and 10 micrometers, fine particles measure 0.1 to 2.5 micrometers, and ultrafine particle are less than 0.1 micrometer. Each size can enter the body through inhalation, but the PM impact on the body varies by size. Coarse particles are filtered by the upper airways and these particles can accumulate and cause pulmonary inflammation. This can result in eye and sinus irritation as well as sore throat and coughing.[265][266] Coarse PM is often composed of materials that are heavier and more toxic that lead to short-term effects with stronger impact.[266]

Smaller particulate moves further into the respiratory system creating issues deep into the lungs and the bloodstream.[265][266] In asthma patients, PM2.5 causes inflammation but also increases oxidative stress in the epithelial cells. These particulates also cause apoptosis and autophagy in lung epithelial cells. Both processes cause the cells to be damaged and impacts the cell function. This damage impacts those with respiratory conditions such as asthma where the lung tissues and function are already compromised.[266] The third PM type is ultra-fine PM (UFP). UFP can enter the bloodstream like PM2.5 however studies show that it works into the blood much quicker. The inflammation and epithelial damage done by UFP has also shown to be much more severe.[266] PM2.5 is of the largest concern in regards to wildfire.[262] This is particularly hazardous to the very young, elderly and those with chronic conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis and cardiovascular conditions. The illnesses most commonly with exposure to the fine particles from wildfire smoke are bronchitis, exacerbation of asthma or COPD, and pneumonia. Symptoms of these complications include wheezing and shortness of breath and cardiovascular symptoms include chest pain, rapid heart rate and fatigue.[265]

Asthma exacerbation

Smoke from wildfires can cause health problems, especially for children and those who already have respiratory problems.[267] Several epidemiological studies have demonstrated a close association between air pollution and respiratory allergic diseases such as bronchial asthma.[262]

An observational study of smoke exposure related to the 2007 San Diego wildfires revealed an increase both in healthcare utilization and respiratory diagnoses, especially asthma among the group sampled.[267] Projected climate scenarios of wildfire occurrences predict significant increases in respiratory conditions among young children.[267] Particulate Matter (PM) triggers a series of biological processes including inflammatory immune response, oxidative stress, which are associated with harmful changes in allergic respiratory diseases.[268]

Although some studies demonstrated no significant acute changes in lung function among people with asthma related to PM from wildfires, a possible explanation for these counterintuitive findings is the increased use of quick-relief medications, such as inhalers, in response to elevated levels of smoke among those already diagnosed with asthma.[269] In investigating the association of medication use for obstructive lung disease and wildfire exposure, researchers found increases both in the usage of inhalers and initiation of long-term control as in oral steroids.[269] More specifically, some people with asthma reported higher use of quick-relief medications (inhalers).[269] After two major wildfires in California, researchers found an increase in physician prescriptions for quick-relief medications in the years following the wildfires than compared to the year before each occurrence.[269]

There is consistent evidence between wildfire smoke and the exacerbation of asthma.[269]

Carbon monoxide danger

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that can be found at the highest concentration at close proximity to a smoldering fire. For this reason, carbon monoxide inhalation is a serious threat to the health of wildfire firefighters. CO in smoke can be inhaled into the lungs where it is absorbed into the bloodstream and reduces oxygen delivery to the body's vital organs. At high concentrations, it can cause headaches, weakness, dizziness, confusion, nausea, disorientation, visual impairment, coma, and even death. However, even at lower concentrations, such as those found at wildfires, individuals with cardiovascular disease may experience chest pain and cardiac arrhythmia.[239] A recent study tracking the number and cause of wildfire firefighter deaths from 1990–2006 found that 21.9% of the deaths occurred from heart attacks.[270]

Another important and somewhat less obvious health effect of wildfires is psychiatric diseases and disorders. Both adults and children from countries ranging from the United States and Canada to Greece and Australia who were directly and indirectly affected by wildfires were found by researchers to demonstrate several different mental conditions linked to their experience with the wildfires. These include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and phobias.[271][272][273][274][275]

In a new twist to wildfire health effects, former uranium mining sites were burned over in the summer of 2012 near North Fork, Idaho. This prompted concern from area residents and Idaho State Department of Environmental Quality officials over the potential spread of radiation in the resultant smoke, since those sites had never been completely cleaned up from radioactive remains.[276]

Epidemiology

The western US has seen an increase in both the frequency and intensity of wildfires over the last several decades. This increase has been attributed to the arid climate of the western US and the effects of global warming. An estimated 46 million people were exposed to wildfire smoke from 2004 to 2009 in the Western United States. Evidence has demonstrated that wildfire smoke can increase levels of particulate matter in the atmosphere.[262]

The EPA has defined acceptable concentrations of particulate matter in the air, through the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and monitoring of ambient air quality has been mandated.[277] Due to these monitoring programs and the incidence of several large wildfires near populated areas, epidemiological studies have been conducted and demonstrate an association between human health effects and an increase in fine particulate matter due to wildfire smoke.

The EPA has defined acceptable concentrations of particulate matter in the air. The National Ambient Air Quality Standards are part of the Clean Air Act and provide mandated guidelines for pollutant levels and the monitoring of ambient air quality.[277] In addition to these monitoring programs, the increased incidence of wildfires near populated areas has precipitated several epidemiological studies. Such studies have demonstrated an association between negative human health effects and an increase in fine particulate matter due to wildfire smoke. The size of the particulate matter is significant as smaller particulate matter (fine) is easily inhaled into the human respiratory tract. Often, small particulate matter can be inhaled into deep lung tissue causing respiratory distress, illness, or disease.[262]

An increase in PM smoke emitted from the Hayman fire in Colorado in June 2002, was associated with an increase in respiratory symptoms in patients with COPD.[278] Looking at the wildfires in Southern California in October 2003 in a similar manner, investigators have shown an increase in hospital admissions due to asthma symptoms while being exposed to peak concentrations of PM in smoke.[279] Another epidemiological study found a 7.2% (95% confidence interval: 0.25%, 15%) increase in risk of respiratory related hospital admissions during smoke wave days with high wildfire-specific particulate matter 2.5 compared to matched non-smoke-wave days.[262]

Children participating in the Children's Health Study were also found to have an increase in eye and respiratory symptoms, medication use and physician visits.[280] Recently, it was demonstrated that mothers who were pregnant during the fires gave birth to babies with a slightly reduced average birth weight compared to those who were not exposed to wildfire during birth. Suggesting that pregnant women may also be at greater risk to adverse effects from wildfire.[281] Worldwide it is estimated that 339,000 people die due to the effects of wildfire smoke each year.[282]

While the size of particulate matter is an important consideration for health effects, the chemical composition of particulate matter (PM2.5) from wildfire smoke should also be considered. Antecedent studies have demonstrated that the chemical composition of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke can yield different estimates of human health outcomes as compared to other sources of smoke.[262] health outcomes for people exposed to wildfire smoke may differ from those exposed to smoke from alternative sources such as solid fuels.

Cultural aspects

Wildfires have a place in many cultures. "To spread like wildfire" is a common idiom in English, meaning something that "quickly affects or becomes known by more and more people".[283] The Smokey Bear fire prevention campaign has yielded one of the most popular characters in the United States; for many years there was a living Smokey Bear mascot, and it has been commemorated on postage stamps.[284]

Wildfire activity has been attributed as a major factor in the development of Ancient Greece. In modern Greece, as in many other regions, it is the most common natural disaster and figures prominently in the social and economic lives of its people.[285]

Science communication

Scientific communication is one of the main tools used to save lives and educate the public on wildfire safety and preparation. There are certain steps that institutions can take in order to communicate effectively with communities and organizations. Some of these include; fostering trust and credibility within communities by using community leaders as spokespeople for information, connecting with individuals by acknowledging concerns, needs, and challenges faced by communities, and utilizing information relevant to the specific targeted community.[286]

In regards to communicating information to the public regarding wildfire safety, some of the most effective ways to communicate with others about wildfires are community outreach conducted through presentations to homeowners and neighborhood associations, community events such as festivals and county fairs, and youth programs.[286]

Another way to communicate effectively is to follow the "Four C's"[286] which are Credentials, Connection, Context, and Catalyst. Credentials mean that one is using credible resources along with personal testimonials when presenting. Connection is the next step and means personal identification with the topic of wildfires as well as acknowledgement of what is already known regarding the specific situation. Context is relating information to how it fits into the lives of community members. And Catalyst is briefing community members on the steps they can follow to keep themselves and each other safe.[286]