A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores. A countercultural movement expresses the ethos and aspirations of a specific population during a well-defined era. When oppositional forces reach critical mass, countercultures can trigger dramatic cultural changes. Prominent examples of countercultures in the Western world include the Levellers (1645–1650), Bohemianism (1850–1910), the Non-conformists of the 1930s, the more fragmentary counterculture of the Beat Generation (1944–1964), followed by the globalized counterculture of the 1960s (1964–1974), usually associated with the hippie subculture as well as the diversified punk subculture of the 1970s and 1980s.

Definition and characteristics

John Milton Yinger originated the term "contraculture" in his 1960 article in American Sociological Review. Yinger suggested the use of the term contraculture "wherever the normative system of a group contains, as a primary element, a theme of conflict with the values of the total society, where personality variables are directly involved in the development and maintenance of the group's values, and wherever its norms can be understood only by reference to the relationships of the group to a surrounding dominant culture."

Some scholars have attributed the counterculture to Theodore Roszak, author of The Making of a Counter Culture. It became prominent in the news media amid the social revolution that swept the Americas, Western Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand during the 1960s.

Scholars differ in the characteristics and specificity they attribute to "counterculture". "Mainstream" culture is of course also difficult to define, and in some ways becomes identified and understood through contrast with counterculture. Counterculture might oppose mass culture (or "media culture"), or middle-class culture and values. Counterculture is sometimes conceptualized in terms of generational conflict and rejection of older or adult values.

Counterculture may or may not be explicitly political. It typically involves criticism or rejection of currently powerful institutions, with accompanying hope for a better life or a new society. It does not look favorably on party politics or authoritarianism.

Cultural development can also be affected by way of counterculture. Scholars such as Joanne Martin and Caren Siehl, deem counterculture and cultural development as "a balancing act, [that] some core values of a counterculture should present a direct challenge to the core values of a dominant culture". Therefore, a prevalent culture and a counterculture should coexist in an uneasy symbiosis, holding opposite positions on valuable issues that are essentially important to each of them. According to this theory, a counterculture can contribute a plethora of useful functions for the prevalent culture, such as "articulating the foundations between appropriate and inappropriate behavior and providing a safe haven for the development of innovative ideas".

During the late 1960s, hippies became the largest and most visible countercultural group in the United States.

According to Sheila Whiteley, "recent developments in sociological theory complicate and problematize theories developed in the 1960s, with digital technology, for example, providing an impetus for new understandings of counterculture". Andy Bennett writes that "despite the theoretical arguments that can be raised against the sociological value of counterculture as a meaningful term for categorising social action, like subculture, the term lives on as a concept in social and cultural theory… [to] become part of a received, mediated memory". However, "this involved not simply the utopian but also the dystopian and that while festivals such as those held at Monterey and Woodstock might appear to embrace the former, the deaths of such iconic figures as Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, the nihilistic mayhem at Altamont, and the shadowy figure of Charles Manson cast a darker light on its underlying agenda, one that reminds us that ‘pathological issues [are] still very much at large in today's world".

Literature

The counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s generated its own unique brand of notable literature, including comics and cartoons, and sometimes referred to as the underground press. In the United States, this includes the work of Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton, and includes Mr. Natural; Keep on Truckin'; Fritz the Cat; Fat Freddy's Cat; Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers; the album cover art for Cheap Thrills; and in several countries contributions to International Times, The Village Voice, and Oz magazine. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, these comics and magazines were available for purchase in head shops along with items like beads, incense, cigarette papers, tie-dye clothing, Day-Glo posters, books, etc.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, some of these shops selling hippie items also became cafés where hippies could hang out, chat, smoke marijuana, read books, etc., e.g. Gandalf's Garden in the King's Road, London, which also published a magazine of the same name. Another such hippie/anarchist bookshop was Mushroom Books, tucked away in the Lace Market area of Nottingham.

Media

Some genres tend to challenge societies with their content that is meant to outright question the norms within cultures and even create change usually towards a more modern way of thought. More often than not, sources of these controversies can be found in art such as Marcel Duchamp whose piece Fountain was meant to be "a calculated attack on the most basic conventions of art" in 1917. Contentious artists like Banksy base most of their works off of mainstream media and culture to bring pieces that usually shock viewers into thinking about their piece in more detail and the themes behind them. A great example can be found in Dismaland, the biggest project of "anarchism" to be organised and exhibited which showcases multiple works such as an "iconic Disney princess's horse-drawn pumpkin carriage, [appearing] to re-enact the death of Princess Diana".

Music

Counterculture is very much evident in music particularly on the basis of the separation of genres into those considered acceptable and within the status quo and those not. Since many minorities groups are already considered counterculture, the music they create and produce may reflect their sociopolitical realities and their musical culture may be adopted as a social expression of their counterculture. This is reflected in dancehall with the concept of base frequencies and base culture in Henriques's "Sonic diaspora", where he expounds that "base denotes crude, debased, unrefined, vulgar, and even animal" for the Jamaican middle class and is associated with the "bottom-end, low frequencies…basic lower frequencies and embodied resonances distinctly inferior to the higher notes" that appear in dancehall. According to Henriques, "base culture is bottom-up popular, street culture, generated by an urban underclass surviving almost entirely outside the formal economy". That the music is low frequency sonically and regarded as reflective of a lower culture shows the influential connection between counterculture and the music produced. Although music may be considered base and counter culture, it may actually enjoy a lot of popularity which can be seen by the labelling of hip hop as a counterculture genre, despite it being one of the most commercially successful and high charting genres.

Assimilation

Many of these artists though once being taboo, have been assimilated into culture and are no longer a source of moral panic since they do not cross overtly controversial topics or challenge staples of current culture. Instead of being a topic to fear, they have initiated subtle trends that other artists and sources of media may follow.

LGBT

Gay liberation (considered a precursor of various modern LGBT social movements) was known for its links to the counterculture of the time (e.g. groups like the Radical Faeries), and for the gay liberationists' intent to transform or abolish fundamental institutions of society such as gender and the nuclear family; in general, the politics were radical, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist in nature. In order to achieve such liberation, consciousness raising and direct action were employed.

At the outset of the 20th century, homosexual acts were punishable offenses in these countries. The prevailing public attitude was that homosexuality was a moral failing that should be punished, as exemplified by Oscar Wilde's 1895 trial and imprisonment for "gross indecency". But even then, there were dissenting views. Sigmund Freud publicly expressed his opinion that homosexuality was "assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development". According to Charles Kaiser's The Gay Metropolis, there were already semi-public gay-themed gatherings by the mid-1930s in the United States (such as the annual drag balls held during the Harlem Renaissance). There were also bars and bathhouses that catered to gay clientele and adopted warning procedures (similar to those used by Prohibition-era speakeasies) to warn customers of police raids. But homosexuality was typically subsumed into bohemian culture, and was not a significant movement in itself.

Eventually, a genuine gay culture began to take root, albeit very discreetly, with its own styles, attitudes and behaviors and industries began catering to this growing demographic group. For example, publishing houses cranked out pulp novels like The Velvet Underground that were targeted directly at gay people. By the early 1960s, openly gay political organizations such as the Mattachine Society were formally protesting abusive treatment toward gay people, challenging the entrenched idea that homosexuality was an aberrant condition, and calling for the decriminalization of homosexuality. Despite very limited sympathy, American society began at least to acknowledge the existence of a sizable population of gays. The film The Boys in the Band, for example, featured negative portrayals of gay men, but at least recognized that they did in fact fraternize with each other (as opposed to being isolated, solitary predators who "victimized" straight men).

Disco music in large part rose out of the New York gay club scene of the early 1970s as a reaction to the stigmatization of gays and other outside groups such as blacks by the counterculture of that era. By later in the decade, disco was dominating the pop charts. The popular Village People and the critically acclaimed Sylvester had gay-themed lyrics and presentation.

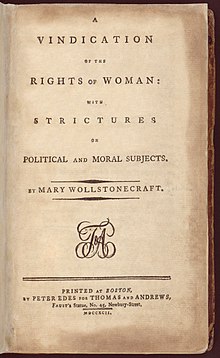

Another element of LGBT counter-culture that began in the 1970s—and continues today—is the lesbian land, landdyke movement, or womyn's land movement. Radical feminists inspired by the back-to-the-land initiative and migrated to rural areas to create communities that were often female-only and/or lesbian communes. "Free Spaces" are defined by Sociologist Francesca Polletta as "small-scale settings within a community or movement that are removed from the direct control of dominant groups, are voluntarily participated in, and generate the cultural challenge that precedes or accompanies political mobilization. Women came together in Free Spaces like music festivals, activist groups and collectives to share ideas with like-minded people and to explore the idea of the lesbian land movement. The movement is closely tied to eco-feminism.

The four tenets of the Landdyke Movement are relationship with the land, liberation and transformation, living the politics, and bodily Freedoms. Most importantly, members of these communities seek to live outside of a patriarchal society that puts emphasis on "beauty ideals that discipline the female body, compulsive heterosexuality, competitiveness with other women, and dependence". Instead of adhering typical female gender roles, the women of Landdyke communities value "self-sufficiency, bodily strength, autonomy from men and patriarchal systems, and the development of lesbian-centered community". Members of the Landdyke movement enjoy bodily freedoms that have been deemed unacceptable in the modern Western world—such as the freedom to expose their breasts, or to go without any clothing at all. An awareness of their impact on the Earth, and connection to nature is essential members of the Landdyke Movement's way of life.

The watershed event in the American gay rights movement was the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City. Following this event, gays and lesbians began to adopt the militant protest tactics used by anti-war and black power radicals to confront anti-gay ideology. Another major turning point was the 1973 decision by the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the official list of mental disorders. Although gay radicals used pressure to force the decision, Kaiser notes that this had been an issue of some debate for many years in the psychiatric community, and that one of the chief obstacles to normalizing homosexuality was that therapists were profiting from offering dubious, unproven "cures".

The AIDS epidemic was initially an unexpected blow to the movement, especially in North America. There was speculation that the disease would permanently drive gay life underground. Ironically, the tables were turned. Many of the early victims of the disease had been openly gay only within the confines of insular "gay ghettos" such as New York City's Greenwich Village and San Francisco's Castro; they remained closeted in their professional lives and to their families. Many heterosexuals who thought they didn't know any gay people were confronted by friends and loved ones dying of "the gay plague" (which soon began to infect heterosexual people also). LGBT communities were increasingly seen not only as victims of a disease, but as victims of ostracism and hatred. Most importantly, the disease became a rallying point for a previously complacent gay community. AIDS invigorated the community politically to fight not only for a medical response to the disease, but also for wider acceptance of homosexuality in mainstream America. Ultimately, coming out became an important step for many LGBT people.

During the early 1980s what was dubbed "New Music", New wave, "New pop" popularized by MTV and associated with gender bending Second British Music Invasion stars such as Boy George and Annie Lennox became what was described by Newsweek at the time as an alternate mainstream to the traditional masculine/heterosexual rock music in the United States.

In 2003, the United States Supreme Court officially declared all sodomy laws unconstitutional in Lawrence v. Texas.

History

Bill Osgerby argues that:

the counterculture's various strands developed from earlier artistic and political movements. On both sides of the Atlantic the 1950s "Beat Generation" had fused existentialist philosophy with jazz, poetry, literature, Eastern mysticism and drugs – themes that were all sustained in the 1960s counterculture.

United States

In the United States, the counterculture of the 1960s became identified with the rejection of conventional social norms of the 1950s. Counterculture youth rejected the cultural standards of their parents, especially with respect to racial segregation and initial widespread support for the Vietnam War, and, less directly, the Cold War—with many young people fearing that America's nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union, coupled with its involvement in Vietnam, would lead to a nuclear holocaust.

In the United States, widespread tensions developed in the 1960s in American society that tended to flow along generational lines regarding the war in Vietnam, race relations, sexual mores, women's rights, traditional modes of authority, and a materialist interpretation of the American Dream. White, middle class youth—who made up the bulk of the counterculture in Western countries—had sufficient leisure time, thanks to widespread economic prosperity, to turn their attention to social issues. These social issues included support for civil rights, women's rights, and gay rights movements, and a rejection of the Vietnam War. The counterculture also had access to a media which was eager to present their concerns to a wider public. Demonstrations for social justice created far-reaching changes affecting many aspects of society. Hippies became the largest countercultural group in the United States.

"The 60s were a leap in human consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Che Guevara, Mother Teresa, they led a revolution of conscience. The Beatles, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix created revolution and evolution themes. The music was like Dalí, with many colors and revolutionary ways. The youth of today must go there to find themselves."

Rejection of mainstream culture was best embodied in the new genres of psychedelic rock music, pop-art and new explorations in spirituality. Musicians who exemplified this era in the United Kingdom and United States included The Beatles, John Lennon, Neil Young, Bob Dylan, The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Frank Zappa, The Rolling Stones, Velvet Underground, Janis Joplin, The Who, Joni Mitchell, The Kinks, Sly and the Family Stone and, in their early years, Chicago. New forms of musical presentation also played a key role in spreading the counterculture, with large outdoor rock festivals being the most noteworthy. The climactic live statement on this occurred from August 15–18, 1969, with the Woodstock Music Festival held in Bethel, New York—with 32 of rock's and psychedelic rock's most popular acts performing live outdoors during the sometimes rainy weekend to an audience of half a million people. (Michael Lang stated 400,000 attended, half of which did not have a ticket.) It is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in popular music history—with Rolling Stone calling it one of the 50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock and Roll. According to Bill Mankin, "It seems fitting… that one of the most enduring labels for the entire generation of that era was derived from a rock festival: the ‘Woodstock Generation’."

Songs, movies, TV shows, and other entertainment media with socially-conscious themes—some allegorical, some literal—became very numerous and popular in the 1960s. Counterculture-specific sentiments expressed in song lyrics and popular sayings of the period included things such as "do your own thing", "turn on, tune in, drop out", "whatever turns you on", "Eight miles high", "sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll", and "light my fire". Spiritually, the counterculture included interest in astrology, the term "Age of Aquarius" and knowing people's astrological signs of the Zodiac. This led Theodore Roszak to state "A [sic] eclectic taste for mystic, occult, and magical phenomena has been a marked characteristic of our postwar youth culture since the days of the beatniks." In the United States, even actor Charlton Heston contributed to the movement, with the statement "Don't trust anyone over thirty" (a saying coined in 1965 by activist Jack Weinberg) in the 1968 film Planet of the Apes; the same year, actress and social activist Jane Fonda starred in the sexually-themed Barbarella. Both actors opposed the Vietnam War during its duration, and Fonda would eventually become controversially active in the peace movement.

The counterculture in the United States has been interpreted as lasting roughly from 1964 to 1972—coincident with America's involvement in Vietnam—and reached its peak in August 1969 at the Woodstock Festival, New York, characterized in part by the film Easy Rider (1969). Unconventional or psychedelic dress; political activism; public protests; campus uprisings; pacifist then loud, defiant music; drugs; communitarian experiments, and sexual liberation were hallmarks of the sixties counterculture—most of whose members were young, white and middle-class.

In the United States, the movement divided the population. To some Americans, these attributes reflected American ideals of free speech, equality, world peace, and the pursuit of happiness; to others, they reflected a self-indulgent, pointlessly rebellious, unpatriotic, and destructive assault on the country's traditional moral order. Authorities banned the psychedelic drug LSD, restricted political gatherings, and tried to enforce bans on what they considered obscenity in books, music, theater, and other media.

The counterculture has been argued to have diminished in the early 1970s, and some have attributed two reasons for this. First, it has been suggested that the most popular of its political goals—civil rights, civil liberties, gender equality, environmentalism, and the end of the Vietnam War—were "accomplished" (to at least some degree); and also that its most popular social attributes—particularly a "live and let live" mentality in personal lifestyles (including, but not limited to the "sexual revolution")—were co-opted by mainstream society. Second, a decline of idealism and hedonism occurred as many notable counterculture figures died, the rest settled into mainstream society and started their own families, and the "magic economy" of the 1960s gave way to the stagflation of the 1970s—the latter costing many in the middle-classes the luxury of being able to live outside conventional social institutions. The counterculture, however, continues to influence social movements, art, music, and society in general, and the post-1973 mainstream society has been in many ways a hybrid of the 1960s establishment and counterculture.

The counterculture movement has been said to be rejuvenated in a way that maintains some similarities from the Counterculture of the 1960s, but it is different as well. Photographer Steve Schapiro investigated and documented these contemporary hippie communities from 2012 to 2014. He traveled the country with his son, attending festival after festival. These findings were compiled in Schapiro’s book Bliss: Transformational Festivals & the Neo Hippie. One of his most valued findings was that these “Neo Hippies” experience and encourage such a spiritual commitment to the community.

Australia

Australia's countercultural trend followed the one burgeoning in the US, and to a lesser extent than the one in Great Britain. Political scandals in the country, such as the disappearance of Harold Holt, and the 1975 constitutional crisis, as well as Australia's involvement in Vietnam War, led to a disillusionment or disengagement with political figures and the government. Large protests were held in the countries most populated cities such as Sydney and Melbourne, one prominent march was held in Sydney in 1971 on George Street. The photographer Roger Scott, who captured the protest in front of the Queen Victoria Building, remarked: "I knew I could make a point with my camera. It was exciting. The old conservative world was ending and a new Australia was beginning. The demonstration was almost silent. The atmosphere was electric. The protesters were committed to making their presence felt … It was clear they wanted to show the government that they were mighty unhappy".

Political upheaval made its way into art in the country: film, music and literature were shaped by the ongoing changes both within the country, the Southern Hemisphere and the rest of the world. Bands such as The Master’s Apprentices, The Pink Finks and Normie Rowe & The Playboys, along with Sydney’s The Easybeats, Billy Thorpe & The Aztecs and The Missing Links began to emerge in the 1960s.

One of Australia's most noted literary voices of the counter-culture movement was Frank Moorhouse, whose collection of short stories, Futility and Other Animals, was first published in Sydney 1969. Its "discontinuous narrative" was said to reflect the "ambience of the counter-culture". Helen Garner's Monkey Grip (1977), released eight years later, is considered a classic example of the contemporary Australian novel, and captured the thriving countercultural movement in Melbourne's inner-city in the mid 1970s, specifically open relationships and recreational drug use. Years later, Garner revealed it was strongly autobiographical and based on her own diaries. Additionally, from the 1960s, surf culture took rise in Australia given the abundance of beaches in the country, and this was reflected in art, from bands such as The Atlantics and novels like Puberty Blues as well as the film of the same name.

As delineations of gender and sexuality have been dismantled, counter-culture in contemporary Melbourne is heavily influenced by the LGBT club scene.

Great Britain

Starting in the late 1960s the counterculture movement spread quickly and pervasively from the US. Britain did not experience the intense social turmoil produced in America by the Vietnam War and racial tensions. Nevertheless, British youth readily identified with their American counterparts' desire to cast off the older generation's social mores. The new music was a powerful weapon. Rock music, which had first been introduced from the US in the 1950s, became a key instrument in the social uprisings of the young generation and Britain soon became a groundswell of musical talent thanks to groups like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Who, Pink Floyd, and more in coming years.

The antiwar movement in Britain closely collaborated with their American counterparts, supporting peasant insurgents in the Asian jungles. The "Ban the Bomb" protests centered around opposition to nuclear weaponry; the campaign gave birth to what was to become the peace symbol of the 1960s.

Russia/Soviet Union

Although not exactly equivalent to the English definition, the term Контркультура (Kontrkul'tura) became common in Russian to define a 1990s cultural movement that promoted acting outside of cultural conventions: the use of explicit language; graphical descriptions of sex, violence and illicit activities; and uncopyrighted use of "safe" characters involved in such activities.

During the early 1970s, the Soviet government rigidly promoted optimism in Russian culture. Divorce and alcohol abuse were viewed as taboo by the media. However, Russian society grew weary of the gap between real life and the creative world, and underground culture became "forbidden fruit". General satisfaction with the quality of existing works led to parody, such as how the Russian anecdotal joke tradition turned the setting of War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy into a grotesque world of sexual excess. Another well-known example is black humor (mostly in the form of short poems) that dealt exclusively with funny deaths and/or other mishaps of small, innocent children.

In the mid-1980s, the Glasnost policy permitted the production of less optimistic works. As a consequence, Russian cinema during the late 1980s and the early 1990s manifested in action movies with explicit (but not necessarily graphic) scenes of ruthless violence and social dramas about drug abuse, prostitution and failing relationships. Although Russian movies of the time would be rated "R" in the United States due to violence, the use of explicit language was much milder than in American cinema.

In the late 1990s, Russian counterculture became increasingly popular on the Internet. Several websites appeared that posted user-created short stories dealing with sex, drugs and violence. The following features are considered the most popular topics in such works:

- Wide use of explicit language;

- Deliberate misspelling;

- Descriptions of drug use and consequences of abuse;

- Negative portrayals of alcohol use;

- Sex and violence: nothing is a taboo – in general, violence is rarely advocated, while all types of sex are considered good;

- Parody: media advertising, classic movies, pop culture and children's books are considered fair game;

- Non-conformance; and

- Politically incorrect topics, mostly racism, xenophobia and homophobia.

A notable aspect of counterculture at the time was the influence of contra-cultural developments on Russian pop culture. In addition to traditional Russian styles of music, such as songs with jail-related lyrics, new music styles with explicit language were developed.

Asia

In the recent past, Dr. Sebastian Kappen, an Indian theologian, has tried to redefine counterculture in the Asian context. In March 1990, at a seminar in Bangalore, he presented his countercultural perspectives (Chapter 4 in S. Kappen, Tradition, modernity, counterculture: an Asian perspective, Visthar, Bangalore, 1994). Dr. Kappen envisages counterculture as a new culture that has to negate the two opposing cultural phenomena in Asian countries:

- invasion by Western capitalist culture, and

- the emergence of revivalist movements.

Kappen writes, "Were we to succumb to the first, we should be losing our identity; if to the second, ours would be a false, obsolete identity in a mental universe of dead symbols and delayed myths".

The most important countercultural movement in India had taken place in the state of West Bengal during the 1960s by a group of poets and artists who called themselves Hungryalists.

See also

- Alternative culture

- Alternative housing

- Alternative lifestyle

- Anti-establishment

- Avant-garde

- Beat generation

- Beatnik

- Bohemianism

- Civil disobedience

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Counter-economics

- Culture jamming

- Dialectic of Enlightenment

- Flag theory

- Flower power

- Freak scene

- Guerrilla theatre

- Hippie movement

- La Movida Madrileña

- Nambassa

- Nonconformity

- Paradigm shift

- Peace movement

- Psychedelic movement

- Punk subculture

- Radicalization

- Rebellion

- Revolution

- Second-wave feminism

- Subculture

- Timeline of 1960s counterculture

- Turn on, tune in, drop out

- Underground (British subculture)

- Underground culture

- User revolt