Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. It can also be the end state of a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term denuclearization is also used to describe the process leading to complete nuclear disarmament.

Disarmament and non-proliferation treaties have been agreed upon because of the extreme danger intrinsic to nuclear war and the possession of nuclear weapons.

Proponents of nuclear disarmament say that it would lessen the probability of nuclear war occurring, especially accidentally. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine deterrence.

Organizations

Nuclear disarmament groups include the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Peace Action, Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, Greenpeace, Soka Gakkai International, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Mayors for Peace, Global Zero, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, and the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. There have been many large anti-nuclear demonstrations and protests. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.

In recent years, some U.S. elder statesmen have also advocated nuclear disarmament. Sam Nunn, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and George Shultz have called upon governments to embrace the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and in various op-ed columns have proposed an ambitious program of urgent steps to that end. The four have created the Nuclear Security Project to advance this agenda. Organisations such as Global Zero, an international non-partisan group of 300 world leaders dedicated to eliminating all nuclear weapons, have also been established.

History

In 1945 in the New Mexico desert, American scientists conducted "Trinity," the first nuclear weapons test, marking the beginning of the atomic age. Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.

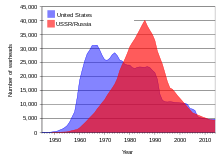

On August 6, 1945, towards the end of World War II, the "Little Boy" device was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division) and killed 70,000–80,000 people outright, with total deaths being around 90,000–146,000. Detonation of the "Fat Man" device exploded over the Japanese city of Nagasaki three days later on August 9, 1945, destroying 60% of the city and killing 35,000–40,000 people outright, though up to 40,000 additional deaths may have occurred over some time after that. Subsequently, the world’s nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.

In 1946 the Truman administration commissioned the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed the international control of the nuclear fuel cycle, revealing atomic energy technology to the USSR, and the decommissioning of all existing nuclear weapons through the new United Nations (UN) system, via the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC). With key modifications, the report became US policy in the form of the Baruch Plan, which was presented to the UNAEC during its first meeting in June 1946. As Cold War tensions emerged, it became clear that Stalin wanted to develop his own atomic bomb and that the United States insisted on an enforcement regime that would have overridden the UN Security Council veto. This soon led to deadlock in the UNAEC.

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads came from scientists and diplomats. Manhattan Project scientists argued that further nuclear testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous. A Los Alamos study warned "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a 'witch's brew' of radioactivity". To prepare the atoll for the nuclear tests, Bikini's native residents were evicted from their homes and resettled on smaller, uninhabited islands where they were unable to sustain themselves.

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon. One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries". The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".

Nuclear disarmament movement

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons". In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Direct Action Committee and supported by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place on Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons. CND organised Aldermaston marches into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day events.

On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.

In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear-weapon testing. The "Baby Tooth Survey," headed by Dr Louise Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass. Public pressure and the research results subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize, describing him as "Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts." Pauling started the International League of Humanists in 1974. He was president of the scientific advisory board of the World Union for Protection of Life and also one of the signatories of the Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement.

In the 1980s, a movement for nuclear disarmament again gained strength in the light of the weapons build-up and statements of US President Ronald Reagan. Reagan had "a world free of nuclear weapons" as his personal mission, and was largely scorned for this in Europe. Reagan was able to start discussions on nuclear disarmament with Soviet Union. He changed the name "SALT" (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) to "START" (Strategic Arms Reduction Talks).

On June 3, 1981, William Thomas launched the White House Peace Vigil in Washington, D.C. He was later joined on the vigil by anti-nuclear activists Concepcion Picciotto and Ellen Benjamin.

On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history. International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983 at 50 sites across the United States. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament. There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.

On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 2008, 2009, and 2010, there have been protests about, and campaigns against, several new nuclear reactor proposals in the United States.

There is an annual protest against U.S. nuclear weapons research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California and in the 2007 protest, 64 people were arrested. There have been a series of protests at the Nevada Test Site and in the April 2007 Nevada Desert Experience protest, 39 people were cited by police. There have been anti-nuclear protests at Naval Base Kitsap for many years, and several in 2008.

In 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize "for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons".

World Peace Council

One of the earliest peace organisations to emerge after the Second World War was the World Peace Council, which was directed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union through the Soviet Peace Committee. Its origins lay in the Communist Information Bureau's (Cominform) doctrine, put forward 1947, that the world was divided between peace-loving progressive forces led by the Soviet Union and warmongering capitalist countries led by the United States. In 1949, Cominform directed that peace "should now become the pivot of the entire activity of the Communist Parties", and most western Communist parties followed this policy. Lawrence Wittner, a historian of the post-war peace movement, argues that the Soviet Union devoted great efforts to the promotion of the WPC in the early post-war years because it feared an American attack and American superiority of arms at a time when the USA possessed the atom bomb but the Soviet Union had not yet developed it.

In 1950, the WPC launched its Stockholm Appeal calling for the absolute prohibition of nuclear weapons. The campaign won support, collecting, it is said, 560 million signatures in Europe, most from socialist countries, including 10 million in France (including that of the young Jacques Chirac), and 155 million signatures in the Soviet Union – the entire adult population. Several non-aligned peace groups who had distanced themselves from the WPC advised their supporters not to sign the Appeal.

The WPC had uneasy relations with the non-aligned peace movement and has been described as being caught in contradictions as "it sought to become a broad world movement while being instrumentalized increasingly to serve foreign policy in the Soviet Union and nominally socialist countries." From the 1950s until the late 1980s it tried to use non-aligned peace organizations to spread the Soviet point of view. At first there was limited co-operation between such groups and the WPC, but western delegates who tried to criticize the Soviet Union or the WPC's silence about Russian armaments were often shouted down at WPC conferences and by the early 1960s they had dissociated themselves from the WPC.

Arms reduction treaties

After the 1986 Reykjavik Summit between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and the new Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, the United States and the Soviet Union concluded two important nuclear arms reduction treaties: the INF Treaty (1987) and START I (1991). After the end of the Cold War, the United States and the Russian Federation concluded the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (2003) and the New START Treaty (2010).

When the extreme danger intrinsic to nuclear war and the possession of nuclear weapons became apparent to all sides during the Cold War, a series of disarmament and nonproliferation treaties were agreed upon between the United States, the Soviet Union, and several other states throughout the world. Many of these treaties involved years of negotiations, and seemed to result in important steps in arms reductions and reducing the risk of nuclear war.

Key treaties

- Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) 1963: Prohibited all testing of nuclear weapons except underground.

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—signed 1968, came into force 1970: An international treaty (currently with 189 member states) to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. The treaty has three main pillars: nonproliferation, disarmament, and the right to peacefully use nuclear technology.

- Interim Agreement on Offensive Arms (SALT I) 1972: The Soviet Union and the United States agreed to a freeze in the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) that they would deploy.

- Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) 1972: The United States and Soviet Union could deploy ABM interceptors at two sites, each with up to 100 ground-based launchers for ABM interceptor missiles. In a 1974 Protocol, the US and Soviet Union agreed to only deploy an ABM system to one site.

- Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) 1979: Replacing SALT I, SALT II limited both the Soviet Union and the United States to an equal number of ICBM launchers, SLBM launchers, and heavy bombers. Also placed limits on Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles (MIRVS).

- Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) 1987: Banned US and Soviet Union land-based ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and missile launchers with ranges of 500–1,000 kilometers (310–620 mi) (short medium-range) and 1,000–5,500 km (620–3,420 mi) (intermediate-range).

- Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I)—signed 1991, ratified 1994: Limited long-range nuclear forces in the United States and the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union to 6,000 attributed warheads on 1,600 ballistic missiles and bombers.

- Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II (START II)—signed 1993, never put into force: START II was a bilateral agreement between the US and Russia which attempted to commit each side to deploy no more than 3,000 to 3,500 warheads by December 2007 and also included a prohibition against deploying multiple independent reentry vehicles (MIRVs) on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs)

- Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT or Moscow Treaty)—signed 2002, into force 2003: A very loose treaty that is often criticized by arms control advocates for its ambiguity and lack of depth, Russia and the United States agreed to reduce their "strategic nuclear warheads" (a term that remained undefined in the treaty) to between 1,700 and 2,200 by 2012. Was superseded by New Start Treaty in 2010.

- Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT)—signed 1996, not yet in force: The CTBT is an international treaty (currently with 181 state signatures and 148 state ratifications) that bans all nuclear explosions in all environments. While the treaty is not in force, Russia has not tested a nuclear weapon since 1990 and the United States has not since 1992.

- New START Treaty—signed 2010, into force in 2011: replaces SORT treaty, reduces deployed nuclear warheads by about half, will remain into force until at least 2021

- Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons—signed 2017, entered into force on January 22, 2021: prohibits possession, manufacture, development, and testing of nuclear weapons, or assistance in such activities, by its parties.

Only one country (South Africa) has been known to ever dismantle an indigenously-developed nuclear arsenal completely. The apartheid government of South Africa produced half a dozen crude fission weapons during the 1980s, but they were dismantled in the early 1990s.

United Nations

In its landmark resolution 1653 of 1961, "Declaration on the prohibition of the use of nuclear and thermo-nuclear weapons," the UN General Assembly stated that use of nuclear weaponry “would exceed even the scope of war and cause indiscriminate suffering and destruction to mankind and civilization and, as such, is contrary to the rules of international law and to the laws of humanity”.

The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) is a department of the United Nations Secretariat established in January 1998 as part of the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan's plan to reform the UN as presented in his report to the General Assembly in July 1997.

Its goal is to promote nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation and the strengthening of the disarmament regimes in respect to other weapons of mass destruction, chemical and biological weapons. It also promotes disarmament efforts in the area of conventional weapons, especially land mines and small arms, which are often the weapons of choice in contemporary conflicts.

Following the retirement of Sergio Duarte in February 2012, Angela Kane was appointed as the new High Representative for Disarmament Affairs.

On July 7, 2017, a UN conference adopted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons with the backing of 122 states. It opened for signature on September 20, 2017.

U.S. nuclear policy

Despite a general trend toward disarmament in the early 2000s, the George W. Bush administration repeatedly pushed to fund policies that would allegedly make nuclear weapons more usable in the post–Cold War environment. To date the U.S. Congress has refused to fund many of these policies. However, some feel that even considering such programs harms the credibility of the United States as a proponent of nonproliferation.

Controversial U.S. nuclear policies

- Reliable Replacement Warhead Program (RRW): This program seeks to replace existing warheads with a smaller number of warhead types designed to be easier to maintain without testing. Critics charge that this would lead to a new generation of nuclear weapons and would increase pressures to test. Congress has not funded this program.

- Complex Transformation: Complex transformation, formerly known as Complex 2030, is an effort to shrink the U.S. nuclear weapons complex and restore the ability to produce "pits", the fissile cores of the primaries of U.S. thermonuclear weapons. Critics see it as an upgrade to the entire nuclear weapons complex to support the production and maintenance of the new generation of nuclear weapons. Congress has not funded this program.

- Nuclear bunker buster: Formally known as the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP), this program aimed to modify an existing gravity bomb to penetrate into soil and rock in order to destroy underground targets. Critics argue that this would lower the threshold for use of nuclear weapons. Congress did not fund this proposal, which was later withdrawn.

- Missile Defense: Formerly known as National Missile Defense, this program seeks to build a network of interceptor missiles to protect the United States and its allies from incoming missiles, including nuclear-armed missiles. Critics have argued that this would impede nuclear disarmament and possibly stimulate a nuclear arms race. Elements of missile defense are being deployed in Poland and the Czech Republic, despite Russian opposition.

Former U.S. officials Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Bill Perry, and Sam Nunn (aka 'The Gang of Four' on nuclear deterrence) proposed in January 2007 that the United States rededicate itself to the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons, concluding: "We endorse setting the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons and working energetically on the actions required to achieve that goal." Arguing a year later that "with nuclear weapons more widely available, deterrence is decreasingly effective and increasingly hazardous," the authors concluded that although "it is tempting and easy to say we can't get there from here, [...] we must chart a course toward that goal." During his presidential campaign, U.S. President-Elect Barack Obama pledged to "set a goal of a world without nuclear weapons, and pursue it."

U.S. programs to reduce risk of nuclear terrorism

The United States has taken the lead in ensuring that nuclear materials globally are properly safeguarded. A popular program that has received bipartisan domestic support for over a decade is the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (CTR). While this program has been deemed a success, many believe that its funding levels need to be increased so as to ensure that all dangerous nuclear materials are secured in the most expeditious manner possible. The CTR program has led to several other innovative and important nonproliferation programs that need to continue to be a budget priority in order to ensure that nuclear weapons do not spread to actors hostile to the United States.

Key programs:

- Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR): The CTR program provides funding to help Russia secure materials that might be used in nuclear or chemical weapons as well as to dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in Russia.

- Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI): Expanding on the success of the CTR, the GTRI will expand nuclear weapons and material securing and dismantlement activities to states outside of the former Soviet Union.

Other states

While the vast majority of states have adhered to the stipulations of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, a few states have either refused to sign the treaty or have pursued nuclear weapons programs while not being members of the treaty. Many view the pursuit of nuclear weapons by these states as a threat to nonproliferation and world peace.

- Declared nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT:

- Indian nuclear weapons: 80–100 active warheads

- Pakistani nuclear weapons: 90–110 active warheads

- North Korean nuclear weapons: <10 active warheads

- Undeclared nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT:

- Israeli nuclear weapons: 75–200 active warheads

- Nuclear weapon states not party to the NPT that disarmed and joined the NPT as non-nuclear weapons states:

- South African nuclear weapons: disarmed from 1989–1993

- Former Soviet states that disarmed and joined the NPT as non-nuclear weapons states:

- Non-nuclear weapon states party to the NPT currently accused of seeking nuclear weapons:

- Non-nuclear weapon states party to the NPT who acknowledged and eliminated past nuclear weapons programs:

Semiotics

The precise use of terminology in the context of disarmament may have important implications for political Signaling theory. In the case of North Korea, "denuclearization" has historically been interpreted as different from "disarmament" by including withdrawal of American nuclear capabilities from the region. More recently, this term has become provocative due to its comparisons to the collapse of the Gaddafi regime after disarmament. The Biden Administration has been criticized for its reaffirming of a strategy of denuclearization with Korea and Japan, as opposed to a "freeze" or "pause" on new nuclear developments.

Similarly, the term "irreversible" has been argued to set an impossible standard for states to disarm.

Recent developments

Eliminating nuclear weapons has long been an aim of the pacifist left. But now many mainstream politicians, academic analysts, and retired military leaders also advocate nuclear disarmament. Sam Nunn, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and George Shultz have called upon governments to embrace the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and in three Wall Street Journal opeds proposed an ambitious program of urgent steps to that end. The four have created the Nuclear Security Project to advance this agenda. Nunn reinforced that agenda during a speech at the Harvard Kennedy School on October 21, 2008, saying, "I’m much more concerned about a terrorist without a return address that cannot be deterred than I am about deliberate war between nuclear powers. You can’t deter a group who is willing to commit suicide. We are in a different era. You have to understand the world has changed." In 2010, the four were featured in a documentary film entitled Nuclear Tipping Point. The film is a visual and historical depiction of the ideas laid forth in the Wall Street Journal op-eds and reinforces their commitment to a world without nuclear weapons and the steps that can be taken to reach that goal.

Global Zero is an international non-partisan group of 300 world leaders dedicated to achieving nuclear disarmament. The initiative, launched in December 2008, promotes a phased withdrawal and verification for the destruction of all devices held by official and unofficial members of the nuclear club. The Global Zero campaign works toward building an international consensus and a sustained global movement of leaders and citizens for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Goals include the initiation of United States-Russia bilateral negotiations for reductions to 1,000 total warheads each and commitments from the other key nuclear weapons countries to participate in multilateral negotiations for phased reductions of nuclear arsenals. Global Zero works to expand the diplomatic dialogue with key governments and continue to develop policy proposals on the critical issues related to the elimination of nuclear weapons.

The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament took place in Oslo in February 2008, and was organized by The Government of Norway, the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Hoover Institute. The Conference was entitled Achieving the Vision of a World Free of Nuclear Weapons and had the purpose of building consensus between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states in relation to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty.

The Tehran International Conference on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation took place in Tehran in April 2010. The conference was held shortly after the signing of the New START, and resulted in a call of action toward eliminating all nuclear weapons. Representatives from 60 countries were invited to the conference. Non-governmental organizations were also present.

Among the prominent figures who have called for the abolition of nuclear weapons are "the philosopher Bertrand Russell, the entertainer Steve Allen, CNN’s Ted Turner, former Senator Claiborne Pell, Notre Dame president Theodore Hesburgh, South African Bishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama".

Others have argued that nuclear weapons have made the world relatively safer, with peace through deterrence and through the stability–instability paradox, including in south Asia. Kenneth Waltz has argued that nuclear weapons have created a nuclear peace, and further nuclear weapon proliferation might even help avoid the large scale conventional wars that were so common prior to their invention at the end of World War II. In the July 2012 issue of Foreign Affairs Waltz took issue with the view of most U.S., European, and Israeli, commentators and policymakers that a nuclear-armed Iran would be unacceptable. Instead Waltz argues that it would probably be the best possible outcome, as it would restore stability to the Middle East by balancing Israel's regional monopoly on nuclear weapons. Professor John Mueller of Ohio State University, the author of Atomic Obsession, has also dismissed the need to interfere with Iran's nuclear program and expressed that arms control measures are counterproductive. During a 2010 lecture at the University of Missouri, which was broadcast by C-SPAN, Dr. Mueller has also argued that the threat from nuclear weapons, especially nuclear terrorism, has been exaggerated, both in the popular media and by officials.

Former Secretary Kissinger says there is a new danger, which cannot be addressed by deterrence: "The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn’t operate in any comparable way". George Shultz has said, "If you think of the people who are doing suicide attacks, and people like that get a nuclear weapon, they are almost by definition not deterrable".

Andrew Bacevich wrote that there is no feasible scenario under which the US could sensibly use nuclear weapons:

For the United States, they are becoming unnecessary, even as a deterrent. Certainly, they are unlikely to dissuade the adversaries most likely to employ such weapons against us -- Islamic extremists intent on acquiring their own nuclear capability. If anything, the opposite is true. By retaining a strategic arsenal in readiness (and by insisting without qualification that the dropping of atomic bombs on two Japanese cities in 1945 was justified), the United States continues tacitly to sustain the view that nuclear weapons play a legitimate role in international politics ... .

In The Limits of Safety, Scott Sagan documented numerous incidents in US military history that could have produced a nuclear war by accident. He concluded:

while the military organizations controlling U.S. nuclear forces during the Cold War performed this task with less success than we know, they performed with more success than we should have reasonably predicted. The problems identified in this book were not the product of incompetent organizations. They reflect the inherent limits of organizational safety. Recognizing that simple truth is the first and most important step toward a safer future.

See also

- Anti-nuclear organizations

- Baruch Plan

- Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

- Countdown to Zero

- International Atomic Energy Agency

- List of anti-war organizations

- List of peace activists

- Nuclear-free zone

- Nuclear proliferation

- Nuclear warfare

- Nuclear weapons and the United States

- Nuclear weapons convention

- Nuclear-Weapon-Ban treaty

- Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone

- Prevention of nuclear catastrophe

- Pacem in terris

- Seabed Arms Control Treaty

- Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT)

- Tehran International Conference on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, 2010