| Anxiety disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

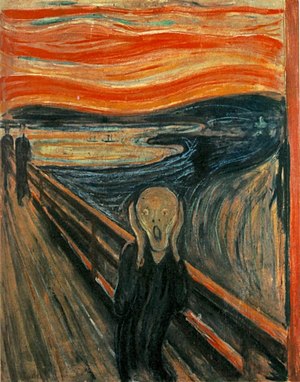

| The Scream (Norwegian: Skrik) a painting by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Symptoms | Worrying, fast heart rate, shakiness |

| Complications | Depression, trouble sleeping, poor quality of life, suicide |

| Usual onset | 15–35 years old |

| Duration | > 6 months |

| Causes | Genetic, environmental, and psychological factors |

| Risk factors | Child abuse, family history, poverty |

| Diagnostic method | Psychological assessment |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyperthyroidism; heart disease; caffeine, alcohol, cannabis use; withdrawal from certain drugs |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, counselling, medications |

| Medication | Antidepressants, anxiolytics, beta blockers |

| Frequency | 12% per year |

Anxiety disorders are a cluster of mental disorders characterized by significant and uncontrollable feelings of anxiety and fear such that a person's social, occupational, and personal function are significantly impaired. Anxiety is a worry about future events, while fear is a reaction to current events. Anxiety may cause physical and cognitive symptoms such as restlessness, irritability, easy fatigability, difficulty concentrating, increased heart rate, chest pain, abdominal pain, and many others. In casual discourse the words anxiety and fear are often used interchangeably; in clinical usage, they have distinct meanings: anxiety is defined as an unpleasant emotional state for which the cause is either not readily identified or perceived to be uncontrollable or unavoidable, whereas fear is an emotional and physiological response to a recognized external threat. The umbrella term anxiety disorder refers to a number of specific disorders that include fears (phobias) or anxiety symptoms.

There are several types of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and selective mutism. The individual disorder can be diagnosed by the specific and unique symptoms, triggering events, and timing. If a person is diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, a medical professional must have evaluated the person to ensure the anxiety cannot be attributed to a medical illness or mental disorder. It is possible for an individual to have more than one anxiety disorder during their life or at the same time. There are numerous treatments and strategies that can improve a person's mood, behaviors, and functioning in daily life.

Sub-types

Generalized anxiety disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common disorder, characterized by long-lasting anxiety which is not focused on any one object or situation. Those suffering from generalized anxiety disorder experience non-specific persistent fear and worry, and become overly concerned with everyday matters. Generalized anxiety disorder is "characterized by chronic excessive worry accompanied by three or more of the following symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, concentration problems, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance". Generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder to affect older adults. Anxiety can be a symptom of a medical or substance use disorder problem, and medical professionals must be aware of this. A diagnosis of GAD is made when a person has been excessively worried about an everyday problem for six months or more. These stresses can include family life, work, social life, or their own health. A person may find that they have problems making daily decisions and remembering commitments as a result of lack of concentration and/or preoccupation with worry. A symptom can be a strained appearance, with increased sweating from the hands, feet, and axillae, and they may be tearful, which can suggest depression. Before a diagnosis of anxiety disorder is made, physicians must rule out drug-induced anxiety and other medical causes.

In children GAD may be associated with headaches, restlessness, abdominal pain, and heart palpitations. Typically it begins around 8 to 9 years of age.

Specific phobias

The single largest category of anxiety disorders is that of specific phobias which includes all cases in which fear and anxiety are triggered by a specific stimulus or situation. Between 5% and 12% of the population worldwide suffer from specific phobias. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, a phobia is an intense fear of- or aversion to- specific objects or situations. Sufferers typically anticipate terrifying consequences from encountering the object of their fear, which can be anything from an animal to a location to a bodily fluid to a particular situation. Common phobias are flying, blood, water, highway driving, and tunnels. When people are exposed to their phobia, they may experience trembling, shortness of breath, or rapid heartbeat. Thus meaning that people with specific phobias often go out of their way to avoid encountering their phobia. People understand that their fear is not proportional to the actual potential danger but still are overwhelmed by it.

Panic disorder

With panic disorder, a person has brief attacks of intense terror and apprehension, often marked by trembling, shaking, confusion, dizziness, nausea, and/or difficulty breathing. These panic attacks, defined by the APA as fear or discomfort that abruptly arises and peaks in less than ten minutes, can last for several hours. Attacks can be triggered by stress, irrational thoughts, general fear or fear of the unknown, or even exercise. However, sometimes the trigger is unclear and the attacks can arise without warning. To help prevent an attack one can avoid the trigger. This can mean avoiding places, people, types of behaviors, or certain situations that have been known to cause a panic attack. This being said not all attacks can be prevented.

In addition to recurrent unexpected panic attacks, a diagnosis of panic disorder requires that said attacks have chronic consequences: either worry over the attacks' potential implications, persistent fear of future attacks, or significant changes in behavior related to the attacks. As such, those suffering from panic disorder experience symptoms even outside specific panic episodes. Often, normal changes in heartbeat are noticed by a panic sufferer, leading them to think something is wrong with their heart or they are about to have another panic attack. In some cases, a heightened awareness (hypervigilance) of body functioning occurs during panic attacks, wherein any perceived physiological change is interpreted as a possible life-threatening illness (i.e., extreme hypochondriasis).

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is the specific anxiety about being in a place or situation where escape is difficult or embarrassing or where help may be unavailable.[21] Agoraphobia is strongly linked with panic disorder and is often precipitated by the fear of having a panic attack. A common manifestation involves needing to be in constant view of a door or other escape route. In addition to the fears themselves, the term agoraphobia is often used to refer to avoidance behaviors that sufferers often develop.[22] For example, following a panic attack while driving, someone suffering from agoraphobia may develop anxiety over driving and will therefore avoid driving. These avoidance behaviors can often have serious consequences and often reinforce the fear they are caused by. In a severe case of someone with Agoraphobia, they may never leave their home.

Social anxiety disorder

Social anxiety disorder (SAD; also known as social phobia) describes an intense fear and avoidance of negative public scrutiny, public embarrassment, humiliation, or social interaction. This fear can be specific to particular social situations (such as public speaking) or, more typically, is experienced in most (or all) social interactions. Roughly 7%. of American adults have Social anxiety disorder, and more than 75% of people experience their first symptoms in their childhood or early teenage years. Social anxiety often manifests specific physical symptoms, including blushing, sweating, rapid heart rate, and difficulty speaking. As with all phobic disorders, those suffering from social anxiety often will attempt to avoid the source of their anxiety; in the case of social anxiety this is particularly problematic, and in severe cases can lead to complete social isolation.

It is important to understand that children are also affected by Social anxiety disorder while attending school. Although their symptoms associated with this disorder are different compared to teenagers and adults. Their symptoms can include difficult processing or retrieving information, sleep deprivation, disruptive behaviors in class, and irregular class participation.

Social physique anxiety (SPA) is a subtype of social anxiety. It is concern over the evaluation of one's body by others. SPA is common among adolescents, especially females.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was once an anxiety disorder (now moved to trauma- and stressor-related disorders in DSM-V) that results from a traumatic experience. PTSD affects approximately 3.5% of U.S. adults every year, and an estimated one in eleven people will be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime. Post-traumatic stress can result from an extreme situation, such as combat, natural disaster, rape, hostage situations, child abuse, bullying, or even a serious accident. It can also result from long-term (chronic) exposure to a severe stressor: for example, soldiers who endure individual battles but cannot cope with continuous combat. Common symptoms include hypervigilance, flashbacks, avoidant behaviors, anxiety, anger and depression. In addition, individuals may experience sleep disturbances. People who suffer from PTSD often try to detach themselves from their friends and family, and have difficulty maintaining these close relationships. There are a number of treatments that form the basis of the care plan for those suffering with PTSD. Such treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), prolonged exposure therapy, stress inoculation therapy, medication, and psychotherapy and support from family and friends.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) research began with Vietnam veterans, as well as natural and non-natural disaster victims. Studies have found the degree of exposure to a disaster has been found to be the best predictor of PTSD.

Separation anxiety disorder

Separation anxiety disorder (SepAD) is the feeling of excessive and inappropriate levels of anxiety over being separated from a person or place. Separation anxiety is a normal part of development in babies or children, and it is only when this feeling is excessive or inappropriate that it can be considered a disorder. Separation anxiety disorder affects roughly 7% of adults and 4% of children, but the childhood cases tend to be more severe; in some instances, even a brief separation can produce panic. Treating a child earlier may prevent problems. This may include training the parents and family on how to deal with it. Often, the parents will reinforce the anxiety because they do not know how to properly work through it with the child. In addition to parent training and family therapy, medication, such as SSRIs, can be used to treat separation anxiety.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is not classified as an anxiety disorder by the DSM-5 but is by the ICD-10. It was previously classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV. It is a condition where the person has obsessions (distressing, persistent, and intrusive thoughts or images) and compulsions (urges to repeatedly perform specific acts or rituals), that are not caused by drugs or physical disorder, and which cause distress or social dysfunction. The compulsive rituals are personal rules followed to relieve the feeling of discomfort. OCD affects roughly 1–2% of adults (somewhat more women than men), and under 3% of children and adolescents.

A person with OCD knows that the symptoms are unreasonable and struggles against both the thoughts and the behavior. Their symptoms could be related to external events they fear (such as their home burning down because they forget to turn off the stove) or worry that they will behave inappropriately.

It is not certain why some people have OCD, but behavioral, cognitive, genetic, and neurobiological factors may be involved. Risk factors include family history, being single (although that may result from the disorder), and higher socioeconomic class or not being in paid employment. Of those with OCD about 20% of people will overcome it, and symptoms will at least reduce over time for most people (a further 50%).

Selective mutism

Selective mutism (SM) is a disorder in which a person who is normally capable of speech does not speak in specific situations or to specific people. Selective mutism usually co-exists with shyness or social anxiety. People with selective mutism stay silent even when the consequences of their silence include shame, social ostracism or even punishment. Selective mutism affects about 0.8% of people at some point in their life.

Testing for selective mutism is important because doctors must determine if it is an issue associated with the child's hearing, movements associated with the jaw or tongue, and if the child can understand when others are speaking to them.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of anxiety disorders is made by symptoms, triggers, and a person's personal and family histories. There are no objective biomarkers or laboratory tests that can diagnose anxiety. It is important for a medical professional to evaluate a person for other medical and mental causes for prolonged anxiety because treatments will vary considerably.

Numerous questionnaires have been developed for clinical use and can be used for an objective scoring system. Symptoms may be vary between each subtype of generalized anxiety disorder. Generally, symptoms must be present for at least six months, occur more days than not, and significantly impair a person's ability to function in daily life. Symptoms may include: feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge; worrying excessively; difficulty concentrating; restlessness; irritability.

Questionnaires developed for clinical use include the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, and the Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale. Other questionnaires combine anxiety and depression measurement, such as the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Examples of specific anxiety questionnaires include the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), the Social Phobia Scale (SPS), and the Social Anxiety Questionnaire (SAQ-A30).

Differential diagnosis

Anxiety disorders differ from developmentally normal fear or anxiety by being excessive or persisting beyond developmentally appropriate periods. They differ from transient fear or anxiety, often stress-induced, by being persistent (e.g., typically lasting 6 months or more), although the criterion for duration is intended as a general guide with allowance for some degree of flexibility and is sometimes of shorter duration in children.

The diagnosis of an anxiety disorder requires first ruling out an underlying medical cause. Diseases that may present similar to an anxiety disorder, including certain endocrine diseases (hypo- and hyperthyroidism, hyperprolactinemia), metabolic disorders (diabetes), deficiency states (low levels of vitamin D, B2, B12, folic acid), gastrointestinal diseases (celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease), heart diseases, blood diseases (anemia), and brain degenerative diseases (Parkinson's disease, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease).

Also, several drugs can cause or worsen anxiety, whether in intoxication, withdrawal, or from chronic use. These include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, sedatives (including prescription benzodiazepines), opioids (including prescription pain killers and illicit drugs like heroin), stimulants (such as caffeine, cocaine and amphetamines), hallucinogens, and inhalants.

Prevention

Focus is increasing on prevention of anxiety disorders. There is tentative evidence to support the use of cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness therapy. A 2013 review found no effective measures to prevent GAD in adults. A 2017 review found that psychological and educational interventions had a small benefit for the prevention of anxiety.

Treatment

Treatment options include lifestyle changes, therapy, and medications. There is no clear evidence as to whether therapy or medication is most effective; the specific medication decision can be made by a doctor and patient with consideration to the patient's specific circumstances and symptoms. If while on treatment with a chosen medication, the person does not improve with his or her anxiety, another medication may be offered. Specific treatments will vary by subtype of anxiety disorder, a person's other medical conditions, and medications.

Lifestyle and diet

Lifestyle changes include exercise, for which there is moderate evidence for some improvement, regularizing sleep patterns, reducing caffeine intake, and stopping smoking. Stopping smoking has benefits in anxiety as large as or larger than those of medications. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as fish oil, may reduce anxiety, particularly in those with more significant symptoms.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective for anxiety disorders and is a first line treatment. CBT appears to be equally effective when carried out via the internet compared to sessions completed face to face.

Mindfulness based programs also appear to be effective for managing anxiety disorders. It is unclear if meditation has an effect on anxiety and transcendental meditation appears to be no different than other types of meditation.

A 2015 Cochrane review of Morita therapy for anxiety disorder in adults found not enough evidence to draw a conclusion.

Medications

First line choices for medications include SSRIs or SNRIs to treat generalized anxiety disorder. There is no good evidence supporting which specific medication in the SSRI or SNRI is best for treating anxiety, so cost often drives drug choice. If they are effective, it is recommended that they are continued for at least a year. Stopping these medications results in a greater risk of relapse.

Buspirone and pregabalin are second-line treatments for people who do not respond to SSRIs or SNRIs; there is also evidence that benzodiazepines including diazepam and clonazepam are effective.

Medications need to be used with care among older adults, who are more likely to have side effects because of coexisting physical disorders. Adherence problems are more likely among older people, who may have difficulty understanding, seeing, or remembering instructions.

In general medications are not seen as helpful in specific phobia but a benzodiazepine is sometimes used to help resolve acute episodes; as 2007 data were sparse for efficacy of any drug.

Alternative medicine

Other remedies have been used or are under research for treating anxiety disorders. As of 2019, there is little evidence for cannabis in anxiety disorders. Kava is under preliminary research for its potential in short-term use by people with mild to moderate anxiety. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends use of kava for mild to moderate anxiety disorders in people not using alcohol or taking other medicines metabolized by the liver, while preferring remedies thought to be natural. Inositol has been found to have modest effects in people with panic disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of St. John's wort, valerian or passionflower.

Neurofeedback training (NFT) training is another form of alternative medicine, where practitioners use monitoring devices to see moment to moment information in relation to the nervous system and the brain. Sensors are placed along the scalp, and the brain responses are recorded and amplified in association with specific brain activity. The practitioners then discuss the responses associated with the client, in an attempt to determine different principles of learning, and practitioner guidance to create changes in brain patterns.

Children

Both therapy and a number of medications have been found to be useful for treating childhood anxiety disorders. Therapy is generally preferred to medication.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a good first therapy approach. Studies have gathered substantial evidence for treatments that are not CBT based as being effective forms of treatment, expanding treatment options for those who do not respond to CBT. Although studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, evidence that it is more effective than treatment as usual, medication, or wait list controls is inconclusive. Like adults, children may undergo psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or counseling. Family therapy is a form of treatment in which the child meets with a therapist together with the primary guardians and siblings. Each family member may attend individual therapy, but family therapy is typically a form of group therapy. Art and play therapy are also used. Art therapy is most commonly used when the child will not or cannot verbally communicate, due to trauma or a disability in which they are nonverbal. Participating in art activities allows the child to express what they otherwise may not be able to communicate to others. In play therapy, the child is allowed to play however they please as a therapist observes them. The therapist may intercede from time to time with a question, comment, or suggestion. This is often most effective when the family of the child plays a role in the treatment.

If a medication option is warranted, antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs can be effective. Minor side effects with medications, however, are common.

Epidemiology

Globally as of 2010 approximately 273 million (4.5% of the population) had an anxiety disorder. It is more common in females (5.2%) than males (2.8%).

In Europe, Africa and Asia, lifetime rates of anxiety disorders are between 9 and 16%, and yearly rates are between 4 and 7%. In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders is about 29% and between 11 and 18% of adults have the condition in a given year. This difference is affected by the range of ways in which different cultures interpret anxiety symptoms and what they consider to be normative behavior. In general, anxiety disorders represent the most prevalent psychiatric condition in the United States, outside of substance use disorder.

Like adults, children can experience anxiety disorders; between 10 and 20 percent of all children will develop a full-fledged anxiety disorder prior to the age of 18, making anxiety the most common mental health issue in young people. Anxiety disorders in children are often more challenging to identify than their adult counterparts owing to the difficulty many parents face in discerning them from normal childhood fears. Likewise, anxiety in children is sometimes misdiagnosed as an attention deficit disorder or, due to the tendency of children to interpret their emotions physically (as stomach aches, head aches, etc.), anxiety disorders may initially be confused with physical ailments.

Anxiety in children has a variety of causes; sometimes anxiety is rooted in biology, and may be a product of another existing condition, such as autism or Asperger's disorder. Gifted children are also often more prone to excessive anxiety than non-gifted children. Other cases of anxiety arise from the child having experienced a traumatic event of some kind, and in some cases, the cause of the child's anxiety cannot be pinpointed.

Anxiety in children tends to manifest along age-appropriate themes, such as fear of going to school (not related to bullying) or not performing well enough at school, fear of social rejection, fear of something happening to loved ones, etc. What separates disordered anxiety from normal childhood anxiety is the duration and intensity of the fears involved.