| Matter is usually classified into three classical states, with plasma sometimes added as a fourth state. From top to bottom: quartz (solid), water (liquid), nitrogen dioxide (gas), and a plasma globe (plasma). |

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic particles, and in everyday as well as scientific usage, "matter" generally includes atoms and anything made up of them, and any particles (or combination of particles) that act as if they have both rest mass and volume. However it does not include massless particles such as photons, or other energy phenomena or waves such as light. Matter exists in various states (also known as phases). These include classical everyday phases such as solid, liquid, and gas – for example water exists as ice, liquid water, and gaseous steam – but other states are possible, including plasma, Bose–Einstein condensates, fermionic condensates, and quark–gluon plasma.

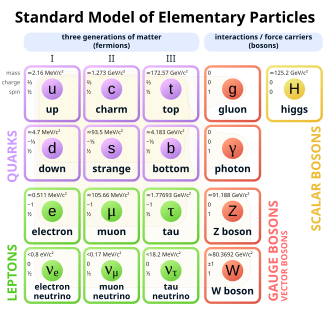

Usually atoms can be imagined as a nucleus of protons and neutrons, and a surrounding "cloud" of orbiting electrons which "take up space". However this is only somewhat correct, because subatomic particles and their properties are governed by their quantum nature, which means they do not act as everyday objects appear to act – they can act like waves as well as particles and they do not have well-defined sizes or positions. In the Standard Model of particle physics, matter is not a fundamental concept because the elementary constituents of atoms are quantum entities which do not have an inherent "size" or "volume" in any everyday sense of the word. Due to the exclusion principle and other fundamental interactions, some "point particles" known as fermions (quarks, leptons), and many composites and atoms, are effectively forced to keep a distance from other particles under everyday conditions; this creates the property of matter which appears to us as matter taking up space.

For much of the history of the natural sciences people have contemplated the exact nature of matter. The idea that matter was built of discrete building blocks, the so-called particulate theory of matter, independently appeared in ancient Greece and ancient India among Buddhists, Hindus and Jains in 1st-millennium BC. Ancient philosophers who proposed the particulate theory of matter include Kanada (c. 6th–century BC or after), Leucippus (~490 BC) and Democritus (~470–380 BC).[8]

Comparison with mass

Matter should not be confused with mass, as the two are not the same in modern physics. Matter is a general term describing any 'physical substance'. By contrast, mass is not a substance but rather a quantitative property of matter and other substances or systems; various types of mass are defined within physics – including but not limited to rest mass, inertial mass, relativistic mass, mass–energy.

While there are different views on what should be considered matter, the mass of a substance has exact scientific definitions. Another difference is that matter has an "opposite" called antimatter, but mass has no opposite—there is no such thing as "anti-mass" or negative mass, so far as is known, although scientists do discuss the concept. Antimatter has the same (i.e. positive) mass property as its normal matter counterpart.

Different fields of science use the term matter in different, and sometimes incompatible, ways. Some of these ways are based on loose historical meanings, from a time when there was no reason to distinguish mass from simply a quantity of matter. As such, there is no single universally agreed scientific meaning of the word "matter". Scientifically, the term "mass" is well-defined, but "matter" can be defined in several ways. Sometimes in the field of physics "matter" is simply equated with particles that exhibit rest mass (i.e., that cannot travel at the speed of light), such as quarks and leptons. However, in both physics and chemistry, matter exhibits both wave-like and particle-like properties, the so-called wave–particle duality.

Definition

Based on atoms

A definition of "matter" based on its physical and chemical structure is: matter is made up of atoms. Such atomic matter is also sometimes termed ordinary matter. As an example, deoxyribonucleic acid molecules (DNA) are matter under this definition because they are made of atoms. This definition can be extended to include charged atoms and molecules, so as to include plasmas (gases of ions) and electrolytes (ionic solutions), which are not obviously included in the atoms definition. Alternatively, one can adopt the protons, neutrons, and electrons definition.

Based on protons, neutrons and electrons

A definition of "matter" more fine-scale than the atoms and molecules definition is: matter is made up of what atoms and molecules are made of, meaning anything made of positively charged protons, neutral neutrons, and negatively charged electrons. This definition goes beyond atoms and molecules, however, to include substances made from these building blocks that are not simply atoms or molecules, for example electron beams in an old cathode ray tube television, or white dwarf matter—typically, carbon and oxygen nuclei in a sea of degenerate electrons. At a microscopic level, the constituent "particles" of matter such as protons, neutrons, and electrons obey the laws of quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality. At an even deeper level, protons and neutrons are made up of quarks and the force fields (gluons) that bind them together, leading to the next definition.

Based on quarks and leptons

As seen in the above discussion, many early definitions of what can be called "ordinary matter" were based upon its structure or "building blocks". On the scale of elementary particles, a definition that follows this tradition can be stated as: "ordinary matter is everything that is composed of quarks and leptons", or "ordinary matter is everything that is composed of any elementary fermions except antiquarks and antileptons". The connection between these formulations follows.

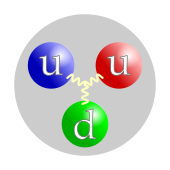

Leptons (the most famous being the electron), and quarks (of which baryons, such as protons and neutrons, are made) combine to form atoms, which in turn form molecules. Because atoms and molecules are said to be matter, it is natural to phrase the definition as: "ordinary matter is anything that is made of the same things that atoms and molecules are made of". (However, notice that one also can make from these building blocks matter that is not atoms or molecules.) Then, because electrons are leptons, and protons, and neutrons are made of quarks, this definition in turn leads to the definition of matter as being "quarks and leptons", which are two of the four types of elementary fermions (the other two being antiquarks and antileptons, which can be considered antimatter as described later). Carithers and Grannis state: "Ordinary matter is composed entirely of first-generation particles, namely the [up] and [down] quarks, plus the electron and its neutrino." (Higher generations particles quickly decay into first-generation particles, and thus are not commonly encountered.)

This definition of ordinary matter is more subtle than it first appears. All the particles that make up ordinary matter (leptons and quarks) are elementary fermions, while all the force carriers are elementary bosons. The W and Z bosons that mediate the weak force are not made of quarks or leptons, and so are not ordinary matter, even if they have mass. In other words, mass is not something that is exclusive to ordinary matter.

The quark–lepton definition of ordinary matter, however, identifies not only the elementary building blocks of matter, but also includes composites made from the constituents (atoms and molecules, for example). Such composites contain an interaction energy that holds the constituents together, and may constitute the bulk of the mass of the composite. As an example, to a great extent, the mass of an atom is simply the sum of the masses of its constituent protons, neutrons and electrons. However, digging deeper, the protons and neutrons are made up of quarks bound together by gluon fields (see dynamics of quantum chromodynamics) and these gluons fields contribute significantly to the mass of hadrons. In other words, most of what composes the "mass" of ordinary matter is due to the binding energy of quarks within protons and neutrons. For example, the sum of the mass of the three quarks in a nucleon is approximately 12.5 MeV/c2, which is low compared to the mass of a nucleon (approximately 938 MeV/c2). The bottom line is that most of the mass of everyday objects comes from the interaction energy of its elementary components.

The Standard Model groups matter particles into three generations, where each generation consists of two quarks and two leptons. The first generation is the up and down quarks, the electron and the electron neutrino; the second includes the charm and strange quarks, the muon and the muon neutrino; the third generation consists of the top and bottom quarks and the tau and tau neutrino. The most natural explanation for this would be that quarks and leptons of higher generations are excited states of the first generations. If this turns out to be the case, it would imply that quarks and leptons are composite particles, rather than elementary particles.

This quark–lepton definition of matter also leads to what can be described as "conservation of (net) matter" laws—discussed later below. Alternatively, one could return to the mass–volume–space concept of matter, leading to the next definition, in which antimatter becomes included as a subclass of matter.

Based on elementary fermions (mass, volume, and space)

A common or traditional definition of matter is "anything that has mass and volume (occupies space)". For example, a car would be said to be made of matter, as it has mass and volume (occupies space).

The observation that matter occupies space goes back to antiquity. However, an explanation for why matter occupies space is recent, and is argued to be a result of the phenomenon described in the Pauli exclusion principle, which applies to fermions. Two particular examples where the exclusion principle clearly relates matter to the occupation of space are white dwarf stars and neutron stars, discussed further below.

Thus, matter can be defined as everything composed of elementary fermions. Although we don't encounter them in everyday life, antiquarks (such as the antiproton) and antileptons (such as the positron) are the antiparticles of the quark and the lepton, are elementary fermions as well, and have essentially the same properties as quarks and leptons, including the applicability of the Pauli exclusion principle which can be said to prevent two particles from being in the same place at the same time (in the same state), i.e. makes each particle "take up space". This particular definition leads to matter being defined to include anything made of these antimatter particles as well as the ordinary quark and lepton, and thus also anything made of mesons, which are unstable particles made up of a quark and an antiquark.

In general relativity and cosmology

In the context of relativity, mass is not an additive quantity, in the sense that one can not add the rest masses of particles in a system to get the total rest mass of the system. Thus, in relativity usually a more general view is that it is not the sum of rest masses, but the energy–momentum tensor that quantifies the amount of matter. This tensor gives the rest mass for the entire system. "Matter" therefore is sometimes considered as anything that contributes to the energy–momentum of a system, that is, anything that is not purely gravity. This view is commonly held in fields that deal with general relativity such as cosmology. In this view, light and other massless particles and fields are all part of "matter".

Structure

In particle physics, fermions are particles that obey Fermi–Dirac statistics. Fermions can be elementary, like the electron—or composite, like the proton and neutron. In the Standard Model, there are two types of elementary fermions: quarks and leptons, which are discussed next.

Quarks

Quarks are massive particles of spin-1⁄2, implying that they are fermions. They carry an electric charge of −1⁄3 e (down-type quarks) or +2⁄3 e (up-type quarks). For comparison, an electron has a charge of −1 e. They also carry colour charge, which is the equivalent of the electric charge for the strong interaction. Quarks also undergo radioactive decay, meaning that they are subject to the weak interaction.

| name | symbol | spin | electric charge (e) |

mass (MeV/c2) |

mass comparable to | antiparticle | antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| up-type quarks | |||||||

| up | u |

1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 1.5 to 3.3 | ~ 5 electrons | antiup | u |

| charm | c |

1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 1160 to 1340 | ~1 proton | anticharm | c |

| top | t |

1⁄2 | +2⁄3 | 169,100 to 173,300 | ~180 protons or ~1 tungsten atom |

antitop | t |

| down-type quarks | |||||||

| down | d |

1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 3.5 to 6.0 | ~10 electrons | antidown | d |

| strange | s |

1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 70 to 130 | ~ 200 electrons | antistrange | s |

| bottom | b |

1⁄2 | −1⁄3 | 4130 to 4370 | ~ 5 protons | antibottom | b |

Baryonic

Baryons are strongly interacting fermions, and so are subject to Fermi–Dirac statistics. Amongst the baryons are the protons and neutrons, which occur in atomic nuclei, but many other unstable baryons exist as well. The term baryon usually refers to triquarks—particles made of three quarks. Also, "exotic" baryons made of four quarks and one antiquark are known as pentaquarks, but their existence is not generally accepted.

Baryonic matter is the part of the universe that is made of baryons (including all atoms). This part of the universe does not include dark energy, dark matter, black holes or various forms of degenerate matter, such as compose white dwarf stars and neutron stars. Microwave light seen by Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), suggests that only about 4.6% of that part of the universe within range of the best telescopes (that is, matter that may be visible because light could reach us from it), is made of baryonic matter. About 26.8% is dark matter, and about 68.3% is dark energy.

The great majority of ordinary matter in the universe is unseen, since visible stars and gas inside galaxies and clusters account for less than 10 per cent of the ordinary matter contribution to the mass–energy density of the universe.

Hadronic

Hadronic matter can refer to 'ordinary' baryonic matter, made from hadrons (baryons and mesons), or quark matter (a generalisation of atomic nuclei), i.e. the 'low' temperature QCD matter. It includes degenerate matter and the result of high energy heavy nuclei collisions.

Degenerate

In physics, degenerate matter refers to the ground state of a gas of fermions at a temperature near absolute zero. The Pauli exclusion principle requires that only two fermions can occupy a quantum state, one spin-up and the other spin-down. Hence, at zero temperature, the fermions fill up sufficient levels to accommodate all the available fermions—and in the case of many fermions, the maximum kinetic energy (called the Fermi energy) and the pressure of the gas becomes very large, and depends on the number of fermions rather than the temperature, unlike normal states of matter.

Degenerate matter is thought to occur during the evolution of heavy stars. The demonstration by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar that white dwarf stars have a maximum allowed mass because of the exclusion principle caused a revolution in the theory of star evolution.

Degenerate matter includes the part of the universe that is made up of neutron stars and white dwarfs.

Strange

Strange matter is a particular form of quark matter, usually thought of as a liquid of up, down, and strange quarks. It is contrasted with nuclear matter, which is a liquid of neutrons and protons (which themselves are built out of up and down quarks), and with non-strange quark matter, which is a quark liquid that contains only up and down quarks. At high enough density, strange matter is expected to be color superconducting. Strange matter is hypothesized to occur in the core of neutron stars, or, more speculatively, as isolated droplets that may vary in size from femtometers (strangelets) to kilometers (quark stars).

Two meanings

In particle physics and astrophysics, the term is used in two ways, one broader and the other more specific.

- The broader meaning is just quark matter that contains three flavors of quarks: up, down, and strange. In this definition, there is a critical pressure and an associated critical density, and when nuclear matter (made of protons and neutrons) is compressed beyond this density, the protons and neutrons dissociate into quarks, yielding quark matter (probably strange matter).

- The narrower meaning is quark matter that is more stable than nuclear matter. The idea that this could happen is the "strange matter hypothesis" of Bodmer and Witten. In this definition, the critical pressure is zero: the true ground state of matter is always quark matter. The nuclei that we see in the matter around us, which are droplets of nuclear matter, are actually metastable, and given enough time (or the right external stimulus) would decay into droplets of strange matter, i.e. strangelets.

Leptons

Leptons are particles of spin-1⁄2, meaning that they are fermions. They carry an electric charge of −1 e (charged leptons) or 0 e (neutrinos). Unlike quarks, leptons do not carry colour charge, meaning that they do not experience the strong interaction. Leptons also undergo radioactive decay, meaning that they are subject to the weak interaction. Leptons are massive particles, therefore are subject to gravity.

| name | symbol | spin | electric charge (e) |

mass (MeV/c2) |

mass comparable to | antiparticle | antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| charged leptons | |||||||

| electron | e− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 0.5110 | 1 electron | antielectron | e+ |

| muon | μ− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 105.7 | ~ 200 electrons | antimuon | μ+ |

| tau | τ− |

1⁄2 | −1 | 1,777 | ~ 2 protons | antitau | τ+ |

| neutrinos | |||||||

| electron neutrino | ν e |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 0.000460 | < 1⁄1000 electron | electron antineutrino | ν e |

| muon neutrino | ν μ |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 0.19 | < 1⁄2 electron | muon antineutrino | ν μ |

| tau neutrino | ν τ |

1⁄2 | 0 | < 18.2 | < 40 electrons | tau antineutrino | ν τ |

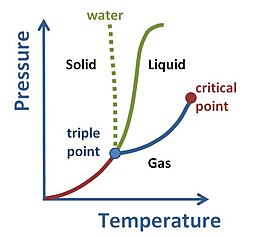

Phases

In bulk, matter can exist in several different forms, or states of aggregation, known as phases, depending on ambient pressure, temperature and volume. A phase is a form of matter that has a relatively uniform chemical composition and physical properties (such as density, specific heat, refractive index, and so forth). These phases include the three familiar ones (solids, liquids, and gases), as well as more exotic states of matter (such as plasmas, superfluids, supersolids, Bose–Einstein condensates, ...). A fluid may be a liquid, gas or plasma. There are also paramagnetic and ferromagnetic phases of magnetic materials. As conditions change, matter may change from one phase into another. These phenomena are called phase transitions, and are studied in the field of thermodynamics. In nanomaterials, the vastly increased ratio of surface area to volume results in matter that can exhibit properties entirely different from those of bulk material, and not well described by any bulk phase (see nanomaterials for more details).

Phases are sometimes called states of matter, but this term can lead to confusion with thermodynamic states. For example, two gases maintained at different pressures are in different thermodynamic states (different pressures), but in the same phase (both are gases).

Antimatter

Baryon asymmetry. Why is there far more matter than antimatter in the observable universe?

Antimatter is matter that is composed of the antiparticles of those that constitute ordinary matter. If a particle and its antiparticle come into contact with each other, the two annihilate; that is, they may both be converted into other particles with equal energy in accordance with Albert Einstein's equation E = mc2. These new particles may be high-energy photons (gamma rays) or other particle–antiparticle pairs. The resulting particles are endowed with an amount of kinetic energy equal to the difference between the rest mass of the products of the annihilation and the rest mass of the original particle–antiparticle pair, which is often quite large. Depending on which definition of "matter" is adopted, antimatter can be said to be a particular subclass of matter, or the opposite of matter.

Antimatter is not found naturally on Earth, except very briefly and in vanishingly small quantities (as the result of radioactive decay, lightning or cosmic rays). This is because antimatter that came to exist on Earth outside the confines of a suitable physics laboratory would almost instantly meet the ordinary matter that Earth is made of, and be annihilated. Antiparticles and some stable antimatter (such as antihydrogen) can be made in tiny amounts, but not in enough quantity to do more than test a few of its theoretical properties.

There is considerable speculation both in science and science fiction as to why the observable universe is apparently almost entirely matter (in the sense of quarks and leptons but not antiquarks or antileptons), and whether other places are almost entirely antimatter (antiquarks and antileptons) instead. In the early universe, it is thought that matter and antimatter were equally represented, and the disappearance of antimatter requires an asymmetry in physical laws called CP (charge-parity) symmetry violation, which can be obtained from the Standard Model, but at this time the apparent asymmetry of matter and antimatter in the visible universe is one of the great unsolved problems in physics. Possible processes by which it came about are explored in more detail under baryogenesis.

Formally, antimatter particles can be defined by their negative baryon number or lepton number, while "normal" (non-antimatter) matter particles have positive baryon or lepton number. These two classes of particles are the antiparticle partners of one another.

In October 2017, scientists reported further evidence that matter and antimatter, equally produced at the Big Bang, are identical, should completely annihilate each other and, as a result, the universe should not exist. This implies that there must be something, as yet unknown to scientists, that either stopped the complete mutual destruction of matter and antimatter in the early forming universe, or that gave rise to an imbalance between the two forms.

Conservation

Two quantities that can define an amount of matter in the quark–lepton sense (and antimatter in an antiquark–antilepton sense), baryon number and lepton number, are conserved in the Standard Model. A baryon such as the proton or neutron has a baryon number of one, and a quark, because there are three in a baryon, is given a baryon number of 1/3. So the net amount of matter, as measured by the number of quarks (minus the number of antiquarks, which each have a baryon number of −1/3), which is proportional to baryon number, and number of leptons (minus antileptons), which is called the lepton number, is practically impossible to change in any process. Even in a nuclear bomb, none of the baryons (protons and neutrons of which the atomic nuclei are composed) are destroyed—there are as many baryons after as before the reaction, so none of these matter particles are actually destroyed and none are even converted to non-matter particles (like photons of light or radiation). Instead, nuclear (and perhaps chromodynamic) binding energy is released, as these baryons become bound into mid-size nuclei having less energy (and, equivalently, less mass) per nucleon compared to the original small (hydrogen) and large (plutonium etc.) nuclei. Even in electron–positron annihilation, there is no net matter being destroyed, because there was zero net matter (zero total lepton number and baryon number) to begin with before the annihilation—one lepton minus one antilepton equals zero net lepton number—and this net amount matter does not change as it simply remains zero after the annihilation.

In short, matter, as defined in physics, refers to baryons and leptons. The amount of matter is defined in terms of baryon and lepton number. Baryons and leptons can be created, but their creation is accompanied by antibaryons or antileptons; and they can be destroyed, by annihilating them with antibaryons or antileptons. Since antibaryons/antileptons have negative baryon/lepton numbers, the overall baryon/lepton numbers aren't changed, so matter is conserved. However, baryons/leptons and antibaryons/antileptons all have positive mass, so the total amount of mass is not conserved. Further, outside of natural or artificial nuclear reactions, there is almost no antimatter generally available in the universe (see baryon asymmetry and leptogenesis), so particle annihilation is rare in normal circumstances.

Dark

Ordinary matter, in the quarks and leptons definition, constitutes about 4% of the energy of the observable universe. The remaining energy is theorized to be due to exotic forms, of which 23% is dark matter and 73% is dark energy.

In astrophysics and cosmology, dark matter is matter of unknown composition that does not emit or reflect enough electromagnetic radiation to be observed directly, but whose presence can be inferred from gravitational effects on visible matter. Observational evidence of the early universe and the Big Bang theory require that this matter have energy and mass, but is not composed ordinary baryons (protons and neutrons). The commonly accepted view is that most of the dark matter is non-baryonic in nature. As such, it is composed of particles as yet unobserved in the laboratory. Perhaps they are supersymmetric particles, which are not Standard Model particles, but relics formed at very high energies in the early phase of the universe and still floating about.

Energy

In cosmology, dark energy is the name given to the source of the repelling influence that is accelerating the rate of expansion of the universe. Its precise nature is currently a mystery, although its effects can reasonably be modeled by assigning matter-like properties such as energy density and pressure to the vacuum itself.

Fully 70% of the matter density in the universe appears to be in the form of dark energy. Twenty-six percent is dark matter. Only 4% is ordinary matter. So less than 1 part in 20 is made out of matter we have observed experimentally or described in the standard model of particle physics. Of the other 96%, apart from the properties just mentioned, we know absolutely nothing.

— Lee Smolin (2007), The Trouble with Physics, p. 16

Exotic

Exotic matter is a concept of particle physics, which may include dark matter and dark energy but goes further to include any hypothetical material that violates one or more of the properties of known forms of matter. Some such materials might possess hypothetical properties like negative mass.

Historical study

Antiquity (c. 600 BC–c. 322 BC)

In ancient India, the Buddhists, the Hindus and the Jains each developed a particulate theory of matter, positing that all matter is made of atoms (paramanu, pudgala) that are in itself "eternal, indestructible and innumerable" and which associate and dissociate according to certain fundamental natural laws to form more complex matter or change over time. They coupled their ideas of soul, or lack thereof, into their theory of matter. The strongest developers and defenders of this theory were the Nyaya-Vaisheshika school, with the ideas of the philosopher Kanada (c. 6th–century BC) being the most followed. The Buddhists also developed these ideas in late 1st-millennium BCE, ideas that were similar to the Vaishashika Hindu school, but one that did not include any soul or conscience. The Jains included soul (jiva), adding qualities such as taste, smell, touch and color to each atom. They extended the ideas found in early literature of the Hindus and Buddhists by adding that atoms are either humid or dry, and this quality cements matter. They also proposed the possibility that atoms combine because of the attraction of opposites, and the soul attaches to these atoms, transforms with karma residue and transmigrates with each rebirth.

In Europe, pre-Socratics speculated the underlying nature of the visible world. Thales (c. 624 BC–c. 546 BC) regarded water as the fundamental material of the world. Anaximander (c. 610 BC–c. 546 BC) posited that the basic material was wholly characterless or limitless: the Infinite (apeiron). Anaximenes (flourished 585 BC, d. 528 BC) posited that the basic stuff was pneuma or air. Heraclitus (c. 535–c. 475 BC) seems to say the basic element is fire, though perhaps he means that all is change. Empedocles (c. 490–430 BC) spoke of four elements of which everything was made: earth, water, air, and fire. Meanwhile, Parmenides argued that change does not exist, and Democritus argued that everything is composed of minuscule, inert bodies of all shapes called atoms, a philosophy called atomism. All of these notions had deep philosophical problems.

Aristotle (384–322 BC) was the first to put the conception on a sound philosophical basis, which he did in his natural philosophy, especially in Physics book I. He adopted as reasonable suppositions the four Empedoclean elements, but added a fifth, aether. Nevertheless, these elements are not basic in Aristotle's mind. Rather they, like everything else in the visible world, are composed of the basic principles matter and form.

For my definition of matter is just this—the primary substratum of each thing, from which it comes to be without qualification, and which persists in the result.

— Aristotle, Physics I:9:192a32

The word Aristotle uses for matter, ὕλη (hyle or hule), can be literally translated as wood or timber, that is, "raw material" for building. Indeed, Aristotle's conception of matter is intrinsically linked to something being made or composed. In other words, in contrast to the early modern conception of matter as simply occupying space, matter for Aristotle is definitionally linked to process or change: matter is what underlies a change of substance. For example, a horse eats grass: the horse changes the grass into itself; the grass as such does not persist in the horse, but some aspect of it—its matter—does. The matter is not specifically described (e.g., as atoms), but consists of whatever persists in the change of substance from grass to horse. Matter in this understanding does not exist independently (i.e., as a substance), but exists interdependently (i.e., as a "principle") with form and only insofar as it underlies change. It can be helpful to conceive of the relationship of matter and form as very similar to that between parts and whole. For Aristotle, matter as such can only receive actuality from form; it has no activity or actuality in itself, similar to the way that parts as such only have their existence in a whole (otherwise they would be independent wholes).

Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

René Descartes (1596–1650) originated the modern conception of matter. He was primarily a geometer. Instead of, like Aristotle, deducing the existence of matter from the physical reality of change, Descartes arbitrarily postulated matter to be an abstract, mathematical substance that occupies space:

So, extension in length, breadth, and depth, constitutes the nature of bodily substance; and thought constitutes the nature of thinking substance. And everything else attributable to body presupposes extension, and is only a mode of extended

— René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy

For Descartes, matter has only the property of extension, so its only activity aside from locomotion is to exclude other bodies: this is the mechanical philosophy. Descartes makes an absolute distinction between mind, which he defines as unextended, thinking substance, and matter, which he defines as unthinking, extended substance. They are independent things. In contrast, Aristotle defines matter and the formal/forming principle as complementary principles that together compose one independent thing (substance). In short, Aristotle defines matter (roughly speaking) as what things are actually made of (with a potential independent existence), but Descartes elevates matter to an actual independent thing in itself.

The continuity and difference between Descartes' and Aristotle's conceptions is noteworthy. In both conceptions, matter is passive or inert. In the respective conceptions matter has different relationships to intelligence. For Aristotle, matter and intelligence (form) exist together in an interdependent relationship, whereas for Descartes, matter and intelligence (mind) are definitionally opposed, independent substances.

Descartes' justification for restricting the inherent qualities of matter to extension is its permanence, but his real criterion is not permanence (which equally applied to color and resistance), but his desire to use geometry to explain all material properties. Like Descartes, Hobbes, Boyle, and Locke argued that the inherent properties of bodies were limited to extension, and that so-called secondary qualities, like color, were only products of human perception.

Isaac Newton (1643–1727) inherited Descartes' mechanical conception of matter. In the third of his "Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy", Newton lists the universal qualities of matter as "extension, hardness, impenetrability, mobility, and inertia". Similarly in Optics he conjectures that God created matter as "solid, massy, hard, impenetrable, movable particles", which were "...even so very hard as never to wear or break in pieces". The "primary" properties of matter were amenable to mathematical description, unlike "secondary" qualities such as color or taste. Like Descartes, Newton rejected the essential nature of secondary qualities.

Newton developed Descartes' notion of matter by restoring to matter intrinsic properties in addition to extension (at least on a limited basis), such as mass. Newton's use of gravitational force, which worked "at a distance", effectively repudiated Descartes' mechanics, in which interactions happened exclusively by contact.

Though Newton's gravity would seem to be a power of bodies, Newton himself did not admit it to be an essential property of matter. Carrying the logic forward more consistently, Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) argued that corporeal properties transcend contact mechanics: chemical properties require the capacity for attraction. He argued matter has other inherent powers besides the so-called primary qualities of Descartes, et al.

19th and 20th centuries

Since Priestley's time, there has been a massive expansion in knowledge of the constituents of the material world (viz., molecules, atoms, subatomic particles). In the 19th century, following the development of the periodic table, and of atomic theory, atoms were seen as being the fundamental constituents of matter; atoms formed molecules and compounds.

The common definition in terms of occupying space and having mass is in contrast with most physical and chemical definitions of matter, which rely instead upon its structure and upon attributes not necessarily related to volume and mass. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the knowledge of matter began a rapid evolution.

Aspects of the Newtonian view still held sway. James Clerk Maxwell discussed matter in his work Matter and Motion. He carefully separates "matter" from space and time, and defines it in terms of the object referred to in Newton's first law of motion.

However, the Newtonian picture was not the whole story. In the 19th century, the term "matter" was actively discussed by a host of scientists and philosophers, and a brief outline can be found in Levere. A textbook discussion from 1870 suggests matter is what is made up of atoms:

Three divisions of matter are recognized in science: masses, molecules and atoms.

A Mass of matter is any portion of matter appreciable by the senses.

A Molecule is the smallest particle of matter into which a body can be divided without losing its identity.

An Atom is a still smaller particle produced by division of a molecule.

Rather than simply having the attributes of mass and occupying space, matter was held to have chemical and electrical properties. In 1909 the famous physicist J. J. Thomson (1856–1940) wrote about the "constitution of matter" and was concerned with the possible connection between matter and electrical charge.

In the late 19th century with the discovery of the electron, and in the early 20th century, with the Geiger–Marsden experiment discovery of the atomic nucleus, and the birth of particle physics, matter was seen as made up of electrons, protons and neutrons interacting to form atoms. There then developed an entire literature concerning the "structure of matter", ranging from the "electrical structure" in the early 20th century, to the more recent "quark structure of matter", introduced as early as 1992 by Jacob with the remark: "Understanding the quark structure of matter has been one of the most important advances in contemporary physics." In this connection, physicists speak of matter fields, and speak of particles as "quantum excitations of a mode of the matter field". And here is a quote from de Sabbata and Gasperini: "With the word "matter" we denote, in this context, the sources of the interactions, that is spinor fields (like quarks and leptons), which are believed to be the fundamental components of matter, or scalar fields, like the Higgs particles, which are used to introduced mass in a gauge theory (and that, however, could be composed of more fundamental fermion fields)."

Protons and neutrons however are not indivisible: they can be divided into quarks. And electrons are part of a particle family called leptons. Both quarks and leptons are elementary particles, and were in 2004 seen by authors of an undergraduate text as being the fundamental constituents of matter.

These quarks and leptons interact through four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, weak interactions, and strong interactions. The Standard Model of particle physics is currently the best explanation for all of physics, but despite decades of efforts, gravity cannot yet be accounted for at the quantum level; it is only described by classical physics (see quantum gravity and graviton) to the frustration of theoreticians like Stephen Hawking. Interactions between quarks and leptons are the result of an exchange of force-carrying particles such as photons between quarks and leptons. The force-carrying particles are not themselves building blocks. As one consequence, mass and energy (which to our present knowledge cannot be created or destroyed) cannot always be related to matter (which can be created out of non-matter particles such as photons, or even out of pure energy, such as kinetic energy). Force mediators are usually not considered matter: the mediators of the electric force (photons) possess energy (see Planck relation) and the mediators of the weak force (W and Z bosons) have mass, but neither are considered matter either. However, while these quanta are not considered matter, they do contribute to the total mass of atoms, subatomic particles, and all systems that contain them.

Summary

The modern conception of matter has been refined many times in history, in light of the improvement in knowledge of just what the basic building blocks are, and in how they interact. The term "matter" is used throughout physics in a wide variety of contexts: for example, one refers to "condensed matter physics", "elementary matter", "partonic" matter, "dark" matter, "anti"-matter, "strange" matter, and "nuclear" matter. In discussions of matter and antimatter, the former has been referred to by Alfvén as koinomatter (Gk. common matter). It is fair to say that in physics, there is no broad consensus as to a general definition of matter, and the term "matter" usually is used in conjunction with a specifying modifier.

The history of the concept of matter is a history of the fundamental length scales used to define matter. Different building blocks apply depending upon whether one defines matter on an atomic or elementary particle level. One may use a definition that matter is atoms, or that matter is hadrons, or that matter is leptons and quarks depending upon the scale at which one wishes to define matter.

These quarks and leptons interact through four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, weak interactions, and strong interactions. The Standard Model of particle physics is currently the best explanation for all of physics, but despite decades of efforts, gravity cannot yet be accounted for at the quantum level; it is only described by classical physics (see quantum gravity and graviton).