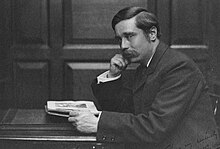

H. G. Wells | |

|---|---|

Photograph by George Charles Beresford, 1920 | |

| Born | Herbert George Wells 21 September 1866 Bromley, Kent, England |

| Died | 13 August 1946 (aged 79) Regent's Park, London, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, teacher, historian, journalist |

| Alma mater | Royal College of Science (Imperial College London) |

| Genre | Science fiction (notably social science fiction), social realism |

| Subject | World history, progress |

| Notable works | |

| Years active | 1895–1946 |

| Spouse | Isabel Mary Wells (1891–1894, divorced) Amy Catherine Robbins (1895–1927, her death) |

| Children | 4, including George Phillip "G. P." Wells and Anthony West |

| Relatives | Joseph Wells (father) Sarah Neal (mother) Simon Wells (great-grandson) |

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer. Prolific in many genres, he wrote dozens of novels, short stories, and works of social commentary, history, satire, biography and autobiography. His work also included two books on recreational war games. Wells is now best remembered for his science fiction novels and is often called the "father of science fiction", along with Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback.

During his own lifetime, however, he was most prominent as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive vision on a global scale. A futurist, he wrote a number of utopian works and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web. His science fiction imagined time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, and biological engineering. Brian Aldiss referred to Wells as the "Shakespeare of science fiction", while American writer Charles Fort referred to him as a "wild talent".

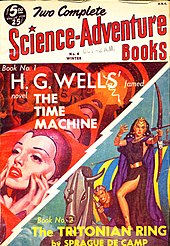

Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption – dubbed “Wells's law” – leading Joseph Conrad to hail him in 1898 as "O Realist of the Fantastic!". His most notable science fiction works include The Time Machine (1895), which was his first novel, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898) and the military science fiction The War in the Air (1907). Wells was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times.

Wells's earliest specialised training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a specifically and fundamentally Darwinian context. He was also an outspoken Socialist from a young age, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathising with pacifist views. His later works became increasingly political and didactic, and he wrote little science fiction, while he sometimes indicated on official documents that his profession was that of journalist. Novels such as Kipps and The History of Mr Polly, which describe lower-middle-class life, led to the suggestion that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens, but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in Tono-Bungay (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. Wells was a diabetic and co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (known today as Diabetes UK) in 1934.

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called "Bertie" by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricketer and Sarah Neal, a former domestic servant. An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper: the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg. To pass the time he began to read books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849, following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, suffered a fractured thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hyde's Drapery Emporium in Southsea. His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices, later inspired his novels The Wheels of Chance, The History of Mr Polly, and Kipps, which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother's being a Protestant and his father's being a freethinker. When his mother returned to work as a lady's maid (at Uppark, a country house in Sussex), one of the conditions of work was that she would not be permitted to have living space for her husband and children. Thereafter, she and Joseph lived separate lives, though they never divorced and remained faithful to each other. As a consequence, Herbert's personal troubles increased as he subsequently failed as a draper and also, later, as a chemist's assistant. However, Uppark had a magnificent library in which he immersed himself, reading many classic works, including Plato's Republic, Thomas More's Utopia, and the works of Daniel Defoe. This was the beginning of Wells's venture into literature.

Teacher

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children. In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune at securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest. The following year, Wells won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science in South Kensington, now part of Imperial College London) in London, studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley. As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909. Wells studied in his new school until 1887, with a weekly allowance of 21 shillings (a guinea) thanks to his scholarship. This ought to have been a comfortable sum of money (at the time many working class families had "round about a pound a week" as their entire household income) yet in his Experiment in Autobiography, Wells speaks of constantly being hungry, and indeed photographs of him at the time show a youth who is very thin and malnourished.

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's Republic, he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of The Science School Journal, a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel The Time Machine was published in the journal under the title The Chronic Argonauts. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.

During 1888, Wells stayed in Stoke-on-Trent, living in Basford. The unique environment of The Potteries was certainly an inspiration. He wrote in a letter to a friend from the area that "the district made an immense impression on me." The inspiration for some of his descriptions in The War of the Worlds is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies. His stay in The Potteries also resulted in the macabre short story "The Cone" (1895, contemporaneous with his famous The Time Machine), set in the north of the city.

After teaching for some time, he was briefly on the staff of Holt Academy in Wales – Wells found it necessary to supplement his knowledge relating to educational principles and methodology and entered the College of Preceptors (College of Teachers). He later received his Licentiate and Fellowship FCP diplomas from the college. It was not until 1890 that Wells earned a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology from the University of London External Programme. In 1889–90, he managed to find a post as a teacher at Henley House School in London, where he taught A. A. Milne (whose father ran the school). His first published work was a Text-Book of Biology in two volumes (1893).

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's residence, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel, whom he later courted. To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as The Pall Mall Gazette, later collecting these in volume form as Select Conversations with an Uncle (1895) and Certain Personal Matters (1897). So prolific did Wells become at this mode of journalism that many of his early pieces remain unidentified. According to David C. Smith, "Most of Wells's occasional pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so ... As a result, many of his early pieces are unknown. It is obvious that many early Wells items have been lost." His success with these shorter pieces encouraged him to write book-length work, and he published his first novel, The Time Machine, in 1895.

Personal life

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to Woking, Surrey, in May 1895. They lived in a rented house, 'Lynton', (now No.141) Maybury Road in the town centre for just under 18 months and married at St Pancras register office in October 1895. His short period in Woking was perhaps the most creative and productive of his whole writing career, for while there he planned and wrote The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, completed The Island of Doctor Moreau, wrote and published The Wonderful Visit and The Wheels of Chance, and began writing two other early books, When the Sleeper Wakes and Love and Mr Lewisham.

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where he constructed a large family home, Spade House, in 1901. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip"; 1901–1985) and Frank Richard (1903–1982) (grandfather of film director Simon Wells). Jane died on 6 October 1927, in Dunmow, at the age of 55.

Wells had affairs with a significant number of women. In December 1909, he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves, whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society. Amber had married the barrister G. R. Blanco White in July of that year, as co-arranged by Wells. After Beatrice Webb voiced disapproval of Wells's "sordid intrigue" with Amber, he responded by lampooning Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney Webb in his 1911 novel The New Machiavelli as 'Altiora and Oscar Bailey', a pair of short-sighted, bourgeois manipulators. Between 1910 and 1913, novelist Elizabeth von Arnim was one of his mistresses. In 1914, he had a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist Rebecca West, 26 years his junior. In 1920–21, and intermittently until his death, he had a love affair with the American birth control activist Margaret Sanger.

Between 1924 and 1933 he partnered with the 22-year younger Dutch adventurer and writer Odette Keun, with whom he lived in Lou Pidou, a house they built together in Grasse, France. Wells dedicated his longest book to her (The World of William Clissold, 1926). When visiting Maxim Gorky in Russia 1920, he had slept with Gorky's mistress Moura Budberg, then still Countess Benckendorf and 27 years his junior. In 1933, when she left Gorky and emigrated to London, their relationship renewed and she cared for him through his final illness. Wells asked her to marry him repeatedly, but Budberg strongly rejected his proposals.

In Experiment in Autobiography (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply". David Lodge's novel A Man of Parts (2011)—a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note)—gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.

Director Simon Wells (born 1961), the author's great-grandson, was a consultant on the future scenes in Back to the Future Part II (1989).

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas". These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006, a book was published on the subject.

Writer

Some of his early novels, called "scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, When the Sleeper Wakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including Kipps and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, Tono-Bungay. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind" (1904).

According to James Gunn, one of Wells's major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his "new system of ideas". In his opinion, the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader knew certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could really happen, today referred to as "the plausible impossible" and "suspension of disbelief". While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts which the readers were not familiar with. He conceived the idea of using a vehicle that allows an operator to travel purposely and selectively forwards or backwards in time. The term "time machine", coined by Wells, is now almost universally used to refer to such a vehicle. He explained that while writing The Time Machine, he realized that "the more impossible the story I had to tell, the more ordinary must be the setting, and the circumstances in which I now set the Time Traveller were all that I could imagine of solid upper-class comforts." In "Wells's Law", a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Therefore, as justifications for the impossible, he employed scientific ideas and theories. Wells's best-known statement of the "law" appears in his introduction to a collection of his works published in 1934:

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.

Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility, but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction. The Island of Doctor Moreau sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection. The earliest depiction of uplift, the novel deals with a number of philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature. In The First Men in the Moon Wells used the idea of radio communication between astronomical objects, a plot point inspired by Nikola Tesla's claim that he had received radio signals from Mars. Though Tono-Bungay is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in The World Set Free (1914). This book contains what is surely his biggest prophetic "hit", with the first description of a nuclear weapon. Scientists of the day were well aware that the natural decay of radium releases energy at a slow rate over thousands of years. The rate of release is too slow to have practical utility, but the total amount released is huge. Wells's novel revolves around an (unspecified) invention that accelerates the process of radioactive decay, producing bombs that explode with no more than the force of ordinary high explosives—but which "continue to explode" for days on end. "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century", he wrote, "than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible ... [but] they did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands". In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction Leó Szilárd read The World Set Free (the same year Sir James Chadwick discovered the neutron), a book which he said made a great impression on him. In addition to writing early science fiction, he produced work dealing with mythological beings like an angel in the novel The Wonderful Visit (1895) and a mermaid in the novel The Sea Lady (1902).

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction bestseller was Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").

His bestselling two-volume work, The Outline of History (1920), began a new era of popularised world history. It received a mixed critical response from professional historians. However, it was very popular amongst the general population and made Wells a rich man. Many other authors followed with "Outlines" of their own in other subjects. He reprised his Outline in 1922 with a much shorter popular work, A Short History of the World, a history book praised by Albert Einstein, and two long efforts, The Science of Life (1930)—written with his son G. P. Wells and evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley, and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931). The "Outlines" became sufficiently common for James Thurber to parody the trend in his humorous essay, "An Outline of Scientists"—indeed, Wells's Outline of History remains in print with a new 2005 edition, while A Short History of the World has been re-edited (2006).

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was A Modern Utopia (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all"; two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (In the Days of the Comet (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in The Shape of Things to Come (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, Things to Come). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist dictators in The Autocracy of Mr Parham (1930) and The Holy Terror (1939). Men Like Gods (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".

Wells contemplates the ideas of nature and nurture and questions humanity in books such as The First Men in the Moon, where nature is completely suppressed by nurture, and The Island of Doctor Moreau, where the strong presence of nature represents a threat to a civilized society. Not all his scientific romances ended in a Utopia, and Wells also wrote a dystopian novel, When the Sleeper Wakes (1899, rewritten as The Sleeper Awakes, 1910), which pictures a future society where the classes have become more and more separated, leading to a revolt of the masses against the rulers. The Island of Doctor Moreau is even darker. The narrator, having been trapped on an island of animals vivisected (unsuccessfully) into human beings, eventually returns to England; like Gulliver on his return from the Houyhnhnms, he finds himself unable to shake off the perceptions of his fellow humans as barely civilised beasts, slowly reverting to their animal natures.

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion's diaries, The Journal of a Disappointed Man, published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the Journal; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries.

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer Florence Deeks unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of The Outline of History had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript, The Web of the World's Romance, which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada. However, it was sworn on oath at the trial that the manuscript remained in Toronto in the safekeeping of Macmillan, and that Wells did not even know it existed, let alone had seen it. The court found no proof of copying, and decided the similarities were due to the fact that the books had similar nature and both writers had access to the same sources. In 2000, A. B. McKillop, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past. According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case. In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Ontario, published an article on Deeks v. Wells. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book. While having some sympathy for Deeks, he argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she received a fair trial, adding that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004).

In 1933, Wells predicted in The Shape of Things to Come that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940, a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II. In 1936, before the Royal Institution, Wells called for the compilation of a constantly growing and changing World Encyclopaedia, to be reviewed by outstanding authorities and made accessible to every human being. In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, World Brain, including the essay "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication. By 1933, he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and book stores. Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller be prevented from speaking. Near the end of World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book".

Wartime works

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells wrote Floor Games (1911) followed by Little Wars (1913), which set out rules for fighting battles with toy soldiers (miniatures). Little Wars is recognised as the first recreational war game and Wells is regarded by gamers and hobbyists as "the Father of Miniature War Gaming". A pacifist prior to the First World War, Wells stated "how much better is this amiable miniature [war] than the real thing". According to Wells, the idea of the game developed from a visit by his friend Jerome K. Jerome. After dinner, Jerome began shooting down toy soldiers with a toy cannon and Wells joined in to compete.

During August 1914, immediately after the outbreak of the First World War, Wells published a number of articles in London newspapers that subsequently appeared as a book entitled The War That Will End War. He coined the expression with the idealistic belief that the result of the war would make a future conflict impossible. Wells blamed the Central Powers for the coming of the war and argued that only the defeat of German militarism could bring about an end to war. Wells used the shorter form of the phrase, "the war to end war", in In the Fourth Year (1918), in which he noted that the phrase "got into circulation" in the second half of 1914. In fact, it had become one of the most common catchphrases of the war.

In 1918 Wells worked for the British War Propaganda Bureau, also called Wellington House. Wells was also one of fifty-three leading British authors — a number that included Rudyard Kipling, Thomas Hardy and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle — who signed their names to the “Authors' Declaration.” This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain “could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war.”

Travels to Russia and the Soviet Union

Wells visited Russia three times: 1914, 1920 and 1934. During his second visit, he saw his old friend Maxim Gorky and with Gorky's help, met Vladimir Lenin. In his book Russia in the Shadows, Wells portrayed Russia as recovering from a total social collapse, "the completest that has ever happened to any modern social organisation." On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the New Statesman magazine, which was extremely rare at that time. He told Stalin how he had seen 'the happy faces of healthy people' in contrast with his previous visit to Moscow in 1920. However, he also criticised the lawlessness, class discrimination, state violence, and absence of free expression. Stalin enjoyed the conversation and replied accordingly. As the chairman of the London-based PEN International, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument. Before he left, he realised that no reform was to happen in the near future.

Final years

Wells’s greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection, George Orwell described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world", and "since 1920 he has squandered his talents in slaying paper dragons." G. K. Chesterton quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".

Wells had diabetes, and was a co-founder in 1934 of The Diabetic Association (now Diabetes UK, the leading charity for people with diabetes in the UK).

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station KTSA in San Antonio, Texas, Wells took part in a radio interview with Orson Welles, who two years previously had performed a famous radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. During the interview, by Charles C Shaw, a KTSA radio host, Wells admitted his surprise at the sensation that resulted from the broadcast but acknowledged his debt to Welles for increasing sales of one of his "more obscure" titles.

Death

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of The War in the Air, Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You damned fools". Wells's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at Old Harry Rocks, the most eastern point of the Jurassic Coast and about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Swanage in Dorset.

A commemorative blue plaque in his honour was installed by the Greater London Council at his home in Regent's Park in 1966.

Futurist

A futurist and “visionary”, Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web. Asserting that "Wells' visions of the future remain unsurpassed", John Higgs, author of Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century, states that in the late 19th century Wells “saw the coming century clearer than anyone else. He anticipated wars in the air, the sexual revolution, motorised transport causing the growth of suburbs and a proto-Wikipedia he called the "world brain". In his novel The World Set Free, he imagined an “atomic bomb” of terrifying power that would be dropped from aeroplanes. This was an extraordinary insight for an author writing in 1913, and it made a deep impression on Winston Churchill."

Many readers have hailed H. G. Wells and George Orwell as special kinds of writers, ones endowed with remarkable prescriptive and prophetic powers. Wells was the twentieth-century prototype of this literary vatic figure: he invented the role, explored its possibilities, especially through new forms of prose and new ways to publish, and defined its boundaries. His impact on his culture was profound; as George Orwell wrote, "The minds of all of us, and therefore the physical world, would be perceptibly different if Wells had never existed."

— The Author as Cultural Hero: H. G. Wells and George Orwell.

In 2011, Wells was among a group of science fiction writers featured in the Prophets of Science Fiction series, a show produced and hosted by film director Sir Ridley Scott, which depicts how predictions influenced the development of scientific advancements by inspiring many readers to assist in transforming those futuristic visions into everyday reality. In a 2013 review of The Time Machine for the New Yorker magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, "At the base of Wells's great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature's Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced "deep time."

Political views

Wells was a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society. Winston Churchill was an avid reader of Wells's books, and after they first met in 1902 they kept in touch until Wells died in 1946. As a junior minister Churchill borrowed lines from Wells for one of his most famous early landmark speeches in 1906, and as Prime Minister the phrase "the gathering storm"—used by Churchill to describe the rise of Nazi Germany—had been written by Wells in The War of the Worlds, which depicts an attack on Britain by Martians. Wells's extensive writings on equality and human rights, most notably his most influential work, The Rights of Man (1940), laid the groundwork for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations shortly after his death.

His efforts regarding the League of Nations, on which he collaborated on the project with Leonard Woolf with the booklets The Idea of a League of Nations, Prolegomena to the Study of World Organization, and The Way of the League of Nations, became a disappointment as the organization turned out to be a weak one unable to prevent the Second World War, which itself occurred towards the very end of his life and only increased the pessimistic side of his nature. In his last book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945), he considered the idea that humanity being replaced by another species might not be a bad idea. He referred to the era between the two World Wars as "The Age of Frustration".

Religious views

Wells's views on God and religion changed over his lifetime. Early in his life he distanced himself from Christianity, and later from theism, and finally, late in life, he was essentially atheistic. Martin Gardner summarises this progression:

[The younger Wells] ... did not object to using the word "God" provided it did not imply anything resembling human personality. In his middle years Wells went through a phase of defending the concept of a "finite God," similar to the god of such process theologians as Samuel Alexander, Edgar Brightman, and Charles Hartshorne. (He even wrote a book about it called God the Invisible King.) Later Wells decided he was really an atheist.

In God the Invisible King (1917), Wells wrote that his idea of God did not draw upon the traditional religions of the world:

This book sets out as forcibly and exactly as possible the religious belief of the writer. [Which] is a profound belief in a personal and intimate God. ... Putting the leading idea of this book very roughly, these two antagonistic typical conceptions of God may be best contrasted by speaking of one of them as God-as-Nature or the Creator, and of the other as God-as-Christ or the Redeemer. One is the great Outward God; the other is the Inmost God. The first idea was perhaps developed most highly and completely in the God of Spinoza. It is a conception of God tending to pantheism, to an idea of a comprehensive God as ruling with justice rather than affection, to a conception of aloofness and awestriking worshipfulness. The second idea, which is contradictory to this idea of an absolute God, is the God of the human heart. The writer suggested that the great outline of the theological struggles of that phase of civilisation and world unity which produced Christianity, was a persistent but unsuccessful attempt to get these two different ideas of God into one focus.

Later in the work, he aligns himself with a "renascent or modern religion ... neither atheist nor Buddhist nor Mohammedan nor Christian ... [that] he has found growing up in himself".

Of Christianity, he said: "it is not now true for me. ... Every believing Christian is, I am sure, my spiritual brother ... but if systemically I called myself a Christian I feel that to most men I should imply too much and so tell a lie". Of other world religions, he writes: "All these religions are true for me as Canterbury Cathedral is a true thing and as a Swiss chalet is a true thing. There they are, and they have served a purpose, they have worked. Only they are not true for me to live in them. ... They do not work for me". In The Fate of Homo Sapiens (1939), Wells criticised almost all world religions and philosophies, stating "there is no creed, no way of living left in the world at all, that really meets the needs of the time… When we come to look at them coolly and dispassionately, all the main religions, patriotic, moral and customary systems in which human beings are sheltering today, appear to be in a state of jostling and mutually destructive movement, like the houses and palaces and other buildings of some vast, sprawling city overtaken by a landslide.

Wells's opposition to organised religion reached a fever pitch in 1943 with publication of his book Crux Ansata, subtitled "An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church".

Literary influence and legacy

The science fiction historian John Clute describes Wells as "the most important writer the genre has yet seen", and notes his work has been central to both British and American science fiction. Science fiction author and critic Algis Budrys said Wells "remains the outstanding expositor of both the hope, and the despair, which are embodied in the technology and which are the major facts of life in our world". He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921, 1932, 1935, and 1946. Wells so influenced real exploration of space that an impact crater on Mars (and the Moon) was named after him.

Wells's genius was his ability to create a stream of brand new, wholly original stories out of thin air. Originality was Wells's calling card. In a six-year stretch from 1895 to 1901, he produced a stream of what he called “scientific romance” novels, which included The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon. This was a dazzling display of new thought, endlessly copied since. A book like The War of the Worlds inspired every one of the thousands of alien invasion stories that followed. It burned its way into the psyche of mankind and changed us all forever.

— Cultural historian John Higgs, The Guardian.

In the United Kingdom, Wells's work was a key model for the British "scientific romance", and other writers in that mode, such as Olaf Stapledon, J. D. Beresford, S. Fowler Wright, and Naomi Mitchison, all drew on Wells's example. Wells was also an important influence on British science fiction of the period after the Second World War, with Arthur C. Clarke and Brian Aldiss expressing strong admiration for Wells's work. Among contemporary British science fiction writers, Stephen Baxter, Christopher Priest and Adam Roberts have all acknowledged Wells's influence on their writing; all three are Vice-Presidents of the H. G. Wells Society. He also had a strong influence on British scientist J. B. S. Haldane, who wrote Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1924), "The Last Judgement" and "On Being the Right Size" from the essay collection Possible Worlds (1927), and Biological Possibilities for the Human Species in the Next Ten Thousand Years (1963), which are speculations about the future of human evolution and life on other planets. Haldane gave several lectures about these topics which in turn influenced other science fiction writers.

In the United States, Hugo Gernsback reprinted most of Wells's work in the pulp magazine Amazing Stories, regarding Wells's work as "texts of central importance to the self-conscious new genre". Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Carl Sagan, and Ursula K. Le Guin all recalled being influenced by Wells.

Sinclair Lewis's early novels were strongly influenced by Wells's realistic social novels, such as The History of Mr Polly; Lewis also named his first son Wells after the author. Lewis nominated H. G. Wells for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1932.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Vladimir Nabokov described Wells as his favourite writer when he was a boy and "a great artist." He went on to cite The Passionate Friends, Ann Veronica, The Time Machine, and The Country of the Blind as superior to anything else written by Wells's British contemporaries. Nabokov said: "His sociological cogitations can be safely ignored, of course, but his romances and fantasies are superb."

Jorge Luis Borges wrote many short pieces on Wells in which he demonstrates a deep familiarity with much of Wells's work. While Borges wrote several critical reviews, including a mostly negative review of Wells's film Things to Come, he regularly treated Wells as a canonical figure of fantastic literature. Late in his life, Borges included The Invisible Man and The Time Machine in his Prologue to a Personal Library, a curated list of 100 great works of literature that he undertook at the behest of the Argentine publishing house Emecé. Canadian author Margaret Atwood read Wells's books, and he also inspired writers of European speculative fiction such as Karel Čapek and Yevgeny Zamyatin.