| Other names | Arteriosclerotic vascular disease (ASVD) |

|---|---|

| |

| The progression of atherosclerosis (narrowing exaggerated) | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, angiology |

| Symptoms | None |

| Complications | Coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, kidney problems |

| Usual onset | Youth (worsens with age) |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, family history, unhealthy diet |

| Prevention | Healthy diet, exercise, not smoking, maintaining a normal weight |

| Medication | Statins, blood pressure medication, aspirin |

| Frequency | ≈100% (>65 years old) |

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis in which the wall of the artery develops abnormalities, called lesions. These lesions may lead to narrowing due to the buildup of atheromatous plaque. Initially, there are generally no symptoms. When severe, it can result in coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, or kidney problems, depending on which arteries are affected. Symptoms, if they occur, generally do not begin until middle age.

The exact cause is not known. Risk factors include abnormal cholesterol levels, elevated levels of inflammatory markers, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, family history, and an unhealthy diet. Plaque is made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances found in the blood. The narrowing of arteries limits the flow of oxygen-rich blood to parts of the body. Diagnosis is based upon a physical exam, electrocardiogram, and exercise stress test, among others.

Prevention is generally by eating a healthy diet, exercising, not smoking, and maintaining a normal weight. Treatment of established disease may include medications to lower cholesterol such as statins, blood pressure medication, or medications that decrease clotting, such as aspirin. A number of procedures may also be carried out such as percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, or carotid endarterectomy.

Atherosclerosis generally starts when a person is young and worsens with age. Almost all people are affected to some degree by the age of 65. It is the number one cause of death and disability in the developed world. Though it was first described in 1575, there is evidence that the condition occurred in people more than 5,000 years ago.

Signs and symptoms

Atherosclerosis is asymptomatic for decades because the arteries enlarge at all plaque locations, thus there is no effect on blood flow. Even most plaque ruptures do not produce symptoms until enough narrowing or closure of an artery, due to clots, occurs. Signs and symptoms only occur after severe narrowing or closure impedes blood flow to different organs enough to induce symptoms. Most of the time, patients realize that they have the disease only when they experience other cardiovascular disorders such as stroke or heart attack. These symptoms, however, still vary depending on which artery or organ is affected.

Abnormalities associated with atherosclerosis begin in childhood. Fibrous and gelatinous lesions have been observed in the coronary arteries of children aged 6–10. Fatty streaks have been observed in the coronary arteries of juveniles aged 11–15, though they appear at a much younger age within the aorta.

Clinically, given enlargement of the arteries for decades, symptomatic atherosclerosis is typically associated with men in their 40s and women in their 50s to 60s. Sub-clinically, the disease begins to appear in childhood and rarely is already present at birth. Noticeable signs can begin developing at puberty. Though symptoms are rarely exhibited in children, early screening of children for cardiovascular diseases could be beneficial to both the child and his/her relatives. While coronary artery disease is more prevalent in men than women, atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries and strokes equally affect both sexes.

Marked narrowing in the coronary arteries, which are responsible for bringing oxygenated blood to the heart, can produce symptoms such as the chest pain of angina and shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, dizziness or light-headedness, breathlessness or palpitations. Abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias—the heart beating either too slowly or too quickly—are another consequence of ischemia.

Carotid arteries supply blood to the brain and neck. Marked narrowing of the carotid arteries can present with symptoms such as: a feeling of weakness; being unable to think straight; difficulty speaking; dizziness; difficulty in walking or standing up straight; blurred vision; numbness of the face, arms and legs; severe headache; and loss of consciousness. These symptoms are also related to stroke (the death of brain cells). Stroke is caused by marked narrowing or closure of arteries going to the brain; lack of adequate blood supply leads to the death of the cells of the affected tissue.

Peripheral arteries, which supply blood to the legs, arms and pelvis, also experience marked narrowing due to plaque rupture and clots. Symptoms of the narrowing are numbness within the arms or legs, as well as pain. Another significant location for plaque formation is the renal arteries, which supply blood to the kidneys. Plaque occurrence and accumulation lead to decreased kidney blood flow and chronic kidney disease, which, like in all other areas, is typically asymptomatic until late stages.

According to United States data for 2004, in about 66% of men and 47% of women, the first symptom of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is a heart attack or sudden cardiac death (death within one hour of onset of the symptom). Cardiac stress testing, traditionally the most commonly performed non-invasive testing method for blood flow limitations, in general, detects only lumen narrowing of ≈75% or greater, although some physicians claim that nuclear stress methods can detect as little as 50%.

Case studies have included autopsies of U.S. soldiers killed in World War II and the Korean War. A much-cited report involved the autopsies of 300 U.S. soldiers killed in Korea. Although the average age of the men was 22.1 years, 77.3 percent had "gross evidence of coronary arteriosclerosis". Other studies done of soldiers in the Vietnam War showed similar results, although often worse than the ones from the earlier wars. Theories include high rates of tobacco use and (in the case of the Vietnam soldiers) the advent of processed foods after World War II.

Risk factors

The atherosclerotic process is not well understood. Atherosclerosis is associated with inflammatory processes in the endothelial cells of the vessel wall associated with retained low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. This retention may be a cause, an effect, or both, of the underlying inflammatory process.

The presence of the plaque induces the muscle cells of the blood vessel to stretch, compensating for the additional bulk, and the endothelial lining thickens, increasing the separation between the plaque and lumen. This somewhat offsets the narrowing caused by the growth of the plaque, but it causes the wall to stiffen and become less compliant to stretching with each heartbeat.

Modifiable

- Bacterial infections

- Diabetes

- Dyslipidemia

- Tobacco smoking

- Trans fat

- Abdominal obesity

- Western pattern diet

- Insulin resistance

- Hypertension

- HIV/AIDS

Nonmodifiable

- South Asian descent

- Advanced age

- Genetic abnormalities

- Family history

- Coronary anatomy and branch pattern

Lesser or uncertain

- Thrombophilia

- Saturated fat

- Excessive carbohydrates

- Elevated triglycerides

- Systemic inflammation

- Hyperinsulinemia

- Sleep deprivation

- Air pollution

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Arsenic poisoning

- Alcohol

- Chronic stress

- Hypothyroidism

- Periodontal disease

Dietary

The relation between dietary fat and atherosclerosis is controversial. The USDA, in its food pyramid, promotes a diet of about 64% carbohydrates from total calories. The American Heart Association, the American Diabetes Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program make similar recommendations. In contrast, Prof Walter Willett (Harvard School of Public Health, PI of the second Nurses' Health Study) recommends much higher levels of fat, especially of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat. These dietary recommendations reach a consensus, though, against consumption of trans fats.

The role of eating oxidized fats (rancid fats) in humans is not clear. Rabbits fed rancid fats develop atherosclerosis faster. Rats fed DHA-containing oils experienced marked disruptions to their antioxidant systems, and accumulated significant amounts of phospholipid hydroperoxide in their blood, livers and kidneys.

Rabbits fed atherogenic diets containing various oils were found to undergo the greatest amount of oxidative susceptibility of LDL via polyunsaturated oils. In another study, rabbits fed heated soybean oil "grossly induced atherosclerosis and marked liver damage were histologically and clinically demonstrated." However, Fred Kummerow claims that it is not dietary cholesterol, but oxysterols, or oxidized cholesterols, from fried foods and smoking, that are the culprit.

Rancid fats and oils taste very unpleasant in even small amounts, so people avoid eating them. It is very difficult to measure or estimate the actual human consumption of these substances. Highly unsaturated omega-3 rich oils such as fish oil, when being sold in pill form, can hide the taste of oxidized or rancid fat that might be present. In the US, the health food industry's dietary supplements are self-regulated and outside of FDA regulations. To properly protect unsaturated fats from oxidation, it is best to keep them cool and in oxygen-free environments.

Pathophysiology

Atherogenesis is the developmental process of atheromatous plaques. It is characterized by a remodeling of arteries leading to subendothelial accumulation of fatty substances called plaques. The buildup of an atheromatous plaque is a slow process, developed over a period of several years through a complex series of cellular events occurring within the arterial wall and in response to a variety of local vascular circulating factors. One recent hypothesis suggests that, for unknown reasons, leukocytes, such as monocytes or basophils, begin to attack the endothelium of the artery lumen in cardiac muscle. The ensuing inflammation leads to the formation of atheromatous plaques in the arterial tunica intima, a region of the vessel wall located between the endothelium and the tunica media. The bulk of these lesions is made of excess fat, collagen, and elastin. At first, as the plaques grow, only wall thickening occurs without any narrowing. Stenosis is a late event, which may never occur and is often the result of repeated plaque rupture and healing responses, not just the atherosclerotic process by itself.

Cellular

Early atherogenesis is characterized by the adherence of blood circulating monocytes (a type of white blood cell) to the vascular bed lining, the endothelium, then by their migration to the sub-endothelial space, and further activation into monocyte-derived macrophages. The primary documented driver of this process is oxidized lipoprotein particles within the wall, beneath the endothelial cells, though upper normal or elevated concentrations of blood glucose also plays a major role and not all factors are fully understood. Fatty streaks may appear and disappear.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles in blood plasma invade the endothelium and become oxidized, creating risk of cardiovascular disease. A complex set of biochemical reactions regulates the oxidation of LDL, involving enzymes (such as Lp-LpA2) and free radicals in the endothelium.

Initial damage to the endothelium results in an inflammatory response. Monocytes enter the artery wall from the bloodstream, with platelets adhering to the area of insult. This may be promoted by redox signaling induction of factors such as VCAM-1, which recruit circulating monocytes, and M-CSF, which is selectively required for the differentiation of monocytes to macrophages. The monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which proliferate locally, ingest oxidized LDL, slowly turning into large "foam cells" – so-called because of their changed appearance resulting from the numerous internal cytoplasmic vesicles and resulting high lipid content. Under the microscope, the lesion now appears as a fatty streak. Foam cells eventually die and further propagate the inflammatory process.

In addition to these cellular activities, there is also smooth muscle proliferation and migration from the tunica media into the intima in response to cytokines secreted by damaged endothelial cells. This causes the formation of a fibrous capsule covering the fatty streak. Intact endothelium can prevent this smooth muscle proliferation by releasing nitric oxide.

Calcification and lipids

Calcification forms among vascular smooth muscle cells of the surrounding muscular layer, specifically in the muscle cells adjacent to atheromas and on the surface of atheroma plaques and tissue. In time, as cells die, this leads to extracellular calcium deposits between the muscular wall and outer portion of the atheromatous plaques. With the atheromatous plaque interfering with the regulation of the calcium deposition, it accumulates and crystallizes. A similar form of intramural calcification, presenting the picture of an early phase of arteriosclerosis, appears to be induced by many drugs that have an antiproliferative mechanism of action (Rainer Liedtke 2008).

Cholesterol is delivered into the vessel wall by cholesterol-containing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. To attract and stimulate macrophages, the cholesterol must be released from the LDL particles and oxidized, a key step in the ongoing inflammatory process. The process is worsened if it is insufficient high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the lipoprotein particle that removes cholesterol from tissues and carries it back to the liver.

The foam cells and platelets encourage the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells, which in turn ingest lipids, become replaced by collagen, and transform into foam cells themselves. A protective fibrous cap normally forms between the fatty deposits and the artery lining (the intima).

These capped fatty deposits (now called 'atheromas') produce enzymes that cause the artery to enlarge over time. As long as the artery enlarges sufficiently to compensate for the extra thickness of the atheroma, then no narrowing ("stenosis") of the opening ("lumen") occurs. The artery becomes expanded with an egg-shaped cross-section, still with a circular opening. If the enlargement is beyond proportion to the atheroma thickness, then an aneurysm is created.

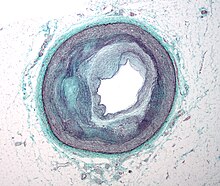

Visible features

Although arteries are not typically studied microscopically, two plaque types can be distinguished:

- The fibro-lipid (fibro-fatty) plaque is characterized by an accumulation of lipid-laden cells underneath the intima of the arteries, typically without narrowing the lumen due to compensatory expansion of the bounding muscular layer of the artery wall. Beneath the endothelium, there is a "fibrous cap" covering the atheromatous "core" of the plaque. The core consists of lipid-laden cells (macrophages and smooth muscle cells) with elevated tissue cholesterol and cholesterol ester content, fibrin, proteoglycans, collagen, elastin, and cellular debris. In advanced plaques, the central core of the plaque usually contains extracellular cholesterol deposits (released from dead cells), which form areas of cholesterol crystals with empty, needle-like clefts. At the periphery of the plaque are younger "foamy" cells and capillaries. These plaques usually produce the most damage to the individual when they rupture. Cholesterol crystals may also play a role.

- The fibrous plaque is also localized under the intima, within the wall of the artery resulting in thickening and expansion of the wall and, sometimes, spotty localized narrowing of the lumen with some atrophy of the muscular layer. The fibrous plaque contains collagen fibers (eosinophilic), precipitates of calcium (hematoxylinophilic), and, rarely, lipid-laden cells.

In effect, the muscular portion of the artery wall forms small aneurysms just large enough to hold the atheroma that are present. The muscular portion of artery walls usually remains strong, even after they have remodeled to compensate for the atheromatous plaques. However, atheromas within the vessel wall are soft and fragile with little elasticity. Arteries constantly expand and contract with each heartbeat, i.e., the pulse. In addition, the calcification deposits between the outer portion of the atheroma and the muscular wall, as they progress, lead to a loss of elasticity and stiffening of the artery as a whole.

The calcification deposits, after they have become sufficiently advanced, are partially visible on coronary artery computed tomography or electron beam tomography (EBT) as rings of increased radiographic density, forming halos around the outer edges of the atheromatous plaques, within the artery wall. On CT, >130 units on the Hounsfield scale (some argue for 90 units) has been the radiographic density usually accepted as clearly representing tissue calcification within arteries. These deposits demonstrate unequivocal evidence of the disease, relatively advanced, even though the lumen of the artery is often still normal by angiography.

Rupture and stenosis

Although the disease process tends to be slowly progressive over decades, it usually remains asymptomatic until an atheroma ulcerates, which leads to immediate blood clotting at the site of the atheroma ulcer. This triggers a cascade of events that leads to clot enlargement, which may quickly obstruct the flow of blood. A complete blockage leads to ischemia of the myocardial (heart) muscle and damage. This process is the myocardial infarction or "heart attack".

If the heart attack is not fatal, fibrous organization of the clot within the lumen ensues, covering the rupture but also producing stenosis or closure of the lumen, or over time and after repeated ruptures, resulting in a persistent, usually localized stenosis or blockage of the artery lumen. Stenoses can be slowly progressive, whereas plaque ulceration is a sudden event that occurs specifically in atheromas with thinner/weaker fibrous caps that have become "unstable".

Repeated plaque ruptures, ones not resulting in total lumen closure, combined with the clot patch over the rupture and healing response to stabilize the clot is the process that produces most stenoses over time. The stenotic areas tend to become more stable despite increased flow velocities at these narrowings. Most major blood-flow-stopping events occur at large plaques, which, before their rupture, produced very little if any stenosis.

From clinical trials, 20% is the average stenosis at plaques that subsequently rupture with resulting complete artery closure. Most severe clinical events do not occur at plaques that produce high-grade stenosis. From clinical trials, only 14% of heart attacks occur from artery closure at plaques producing a 75% or greater stenosis before the vessel closing.

If the fibrous cap separating a soft atheroma from the bloodstream within the artery ruptures, tissue fragments are exposed and released. These tissue fragments are very clot-promoting, containing collagen and tissue factor; they activate platelets and activate the system of coagulation. The result is the formation of a thrombus (blood clot) overlying the atheroma, which obstructs blood flow acutely. With the obstruction of blood flow, downstream tissues are starved of oxygen and nutrients. If this is the myocardium (heart muscle) angina (cardiac chest pain) or myocardial infarction (heart attack) develops.

Accelerated growth of plaques

The distribution of atherosclerotic plaques in a part of arterial endothelium is inhomogeneous. The multiple and focal development of atherosclerotic changes is similar to that in the development of amyloid plaques in the brain and that of age spots on the skin. Misrepair-accumulation aging theory suggests that misrepair mechanisms play an important role in the focal development of atherosclerosis. Development of a plaque is a result of repair of injured endothelium. Because of the infusion of lipids into sub-endothelium, the repair has to end up with altered remodeling of local endothelium. This is the manifestation of a misrepair. Important is this altered remodeling makes the local endothelium have increased fragility to damage and have reduced repair efficiency. As a consequence, this part of endothelium has an increased risk factor of being injured and improperly repaired. Thus, the accumulation of misrepairs of endothelium is focalized and self-accelerating. In this way, the growing of a plaque is also self-accelerating. Within a part of the arterial wall, the oldest plaque is always the biggest, and is the most dangerous one to cause blockage of a local artery.

Components

The plaque is divided into three distinct components:

- The atheroma ("lump of gruel", from Greek ἀθήρα (athera) 'gruel'), which is the nodular accumulation of a soft, flaky, yellowish material at the center of large plaques, composed of macrophages nearest the lumen of the artery

- Underlying areas of cholesterol crystals

- Calcification at the outer base of older or more advanced lesions. Atherosclerotic lesions, or atherosclerotic plaques, are separated into two broad categories: Stable and unstable (also called vulnerable). The pathobiology of atherosclerotic lesions is very complicated, but generally, stable atherosclerotic plaques, which tend to be asymptomatic, are rich in extracellular matrix and smooth muscle cells. On the other hand, unstable plaques are rich in macrophages and foam cells, and the extracellular matrix separating the lesion from the arterial lumen (also known as the fibrous cap) is usually weak and prone to rupture. Ruptures of the fibrous cap expose thrombogenic material, such as collagen, to the circulation and eventually induce thrombus formation in the lumen. Upon formation, intraluminal thrombi can occlude arteries outright (e.g., coronary occlusion), but more often they detach, move into the circulation, and eventually occlude smaller downstream branches causing thromboembolism.

Apart from thromboembolism, chronically expanding atherosclerotic lesions can cause complete closure of the lumen. Chronically expanding lesions are often asymptomatic until lumen stenosis is so severe (usually over 80%) that blood supply to downstream tissue(s) is insufficient, resulting in ischemia. These complications of advanced atherosclerosis are chronic, slowly progressive, and cumulative. Most commonly, soft plaque suddenly ruptures, causing the formation of a thrombus that will rapidly slow or stop blood flow, leading to the death of the tissues fed by the artery in approximately five minutes. This event is called an infarction.

Diagnosis

Areas of severe narrowing, stenosis, detectable by angiography, and to a lesser extent "stress testing" have long been the focus of human diagnostic techniques for cardiovascular disease, in general. However, these methods focus on detecting only severe narrowing, not the underlying atherosclerosis disease. As demonstrated by human clinical studies, most severe events occur in locations with heavy plaque, yet little or no lumen narrowing present before debilitating events suddenly occur. Plaque rupture can lead to artery lumen occlusion within seconds to minutes, and potential permanent debility, and sometimes sudden death.

Plaques that have ruptured are called complicated plaques. The extracellular matrix of the lesion breaks, usually at the shoulder of the fibrous cap that separates the lesion from the arterial lumen, where the exposed thrombogenic components of the plaque, mainly collagen will trigger thrombus formation. The thrombus then travels downstream to other blood vessels, where the blood clot may partially or completely block blood flow. If the blood flow is completely blocked, cell deaths occur due to the lack of oxygen supply to nearby cells, resulting in necrosis. The narrowing or obstruction of blood flow can occur in any artery within the body. Obstruction of arteries supplying the heart muscle results in a heart attack, while the obstruction of arteries supplying the brain results in an ischaemic stroke.

Lumen stenosis that is greater than 75% was considered the hallmark of clinically significant disease in the past because recurring episodes of angina and abnormalities in stress tests are only detectable at that particular severity of stenosis. However, clinical trials have shown that only about 14% of clinically debilitating events occur at sites with more than 75% stenosis. The majority of cardiovascular events that involve sudden rupture of the atheroma plaque do not display any evident narrowing of the lumen. Thus, greater attention has been focused on "vulnerable plaque" from the late 1990s onwards.

Besides the traditional diagnostic methods such as angiography and stress-testing, other detection techniques have been developed in the past decades for earlier detection of atherosclerotic disease. Some of the detection approaches include anatomical detection and physiologic measurement.

Examples of anatomical detection methods include coronary calcium scoring by CT, carotid IMT (intimal media thickness) measurement by ultrasound, and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS). Examples of physiologic measurement methods include lipoprotein subclass analysis, HbA1c, hs-CRP, and homocysteine. Both anatomic and physiologic methods allow early detection before symptoms show up, disease staging, and tracking of disease progression. Anatomic methods are more expensive and some of them are invasive in nature, such as IVUS. On the other hand, physiologic methods are often less expensive and safer. But they do not quantify the current state of the disease or directly track progression. In recent years, developments in nuclear imaging techniques such as PET and SPECT have provided ways of estimating the severity of atherosclerotic plaques.

Prevention

Up to 90% of cardiovascular disease may be preventable if established risk factors are avoided. Medical management of atherosclerosis first involves modification to risk factors–for example, via smoking cessation and diet restrictions. Prevention then is generally by eating a healthy diet, exercising, not smoking, and maintaining a normal weight.

Diet

Changes in diet may help prevent the development of atherosclerosis. Tentative evidence suggests that a diet containing dairy products has no effect on or decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

A diet high in fruits and vegetables decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. Evidence suggests that the Mediterranean diet may improve cardiovascular results. There is also evidence that a Mediterranean diet may be better than a low-fat diet in bringing about long-term changes to cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., lower cholesterol level and blood pressure).

Exercise

A controlled exercise program combats atherosclerosis by improving circulation and functionality of the vessels. Exercise is also used to manage weight in patients who are obese, lower blood pressure, and decrease cholesterol. Often lifestyle modification is combined with medication therapy. For example, statins help to lower cholesterol. Antiplatelet medications like aspirin help to prevent clots, and a variety of antihypertensive medications are routinely used to control blood pressure. If the combined efforts of risk factor modification and medication therapy are not sufficient to control symptoms or fight imminent threats of ischemic events, a physician may resort to interventional or surgical procedures to correct the obstruction.

Treatment

Treatment of established disease may include medications to lower cholesterol such as statins, blood pressure medication, or medications that decrease clotting, such as aspirin. A number of procedures may also be carried out such as percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, or carotid endarterectomy.

Medical treatments often focus on alleviating symptoms. However measures which focus on decreasing underlying atherosclerosis—as opposed to simply treating symptoms—are more effective. Non-pharmaceutical means are usually the first method of treatment, such as stopping smoking and practicing regular exercise. If these methods do not work, medicines are usually the next step in treating cardiovascular diseases and, with improvements, have increasingly become the most effective method over the long term.

The key to the more effective approaches is to combine multiple different treatment strategies. In addition, for those approaches, such as lipoprotein transport behaviors, which have been shown to produce the most success, adopting more aggressive combination treatment strategies taken on a daily basis and indefinitely has generally produced better results, both before and especially after people are symptomatic.

Statins

The group of medications referred to as statins are widely prescribed for treating atherosclerosis. They have shown benefit in reducing cardiovascular disease and mortality in those with high cholesterol with few side effects. Secondary prevention therapy, which includes high-intensity statins and aspirin, is recommended by multi-society guidelines for all patients with history of ASCVD (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) to prevent recurrence of coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, or peripheral arterial disease. However, prescription of and adherence to these guideline-concordant therapies is lacking, particularly among young patients and women.

Statins work by inhibiting HMG-CoA (hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A) reductase, a hepatic rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol's biochemical production pathway. By inhibiting this rate-limiting enzyme, the body is unable to produce cholesterol endogenously, therefore reducing serum LDL-cholesterol. This reduced endogenous cholesterol production triggers the body to then pull cholesterol from other cellular sources, enhancing serum HDL-cholesterol. These data are primarily in middle-age men and the conclusions are less clear for women and people over the age of 70.

Surgery

When atherosclerosis has become severe and caused irreversible ischemia, such as tissue loss in the case of peripheral artery disease, surgery may be indicated. Vascular bypass surgery can re-establish flow around the diseased segment of artery, and angioplasty with or without stenting can reopen narrowed arteries and improve blood flow. Coronary artery bypass grafting without manipulation of the ascending aorta has demonstrated reduced rates of postoperative stroke and mortality compared to traditional on-pump coronary revascularization.

Other

There is evidence that some anticoagulants, particularly warfarin, which inhibit clot formation by interfering with Vitamin K metabolism, may actually promote arterial calcification in the long term despite reducing clot formation in the short term. Also, single peptides such as 3-hydroxybenzaldehyde and protocatechuic aldehyde have shown vasculoprotective effects to reduce risk of atherosclerosis.

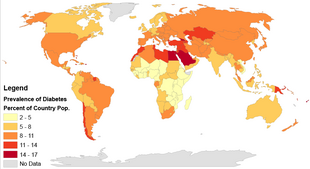

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular disease, which is predominantly the clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis, is the leading cause of death worldwide.

Etymology

The following terms are similar, yet distinct, in both spelling and meaning, and can be easily confused: arteriosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis is a general term describing any hardening (and loss of elasticity) of medium or large arteries (from Greek ἀρτηρία (artēria) 'artery', and σκλήρωσις (sklerosis) 'hardening'); arteriolosclerosis is any hardening (and loss of elasticity) of arterioles (small arteries); atherosclerosis is a hardening of an artery specifically due to an atheromatous plaque (from Ancient Greek ἀθήρα (athḗra) 'gruel'). The term atherogenic is used for substances or processes that cause formation of atheroma.

Economics

In 2011, coronary atherosclerosis was one of the top ten most expensive conditions seen during inpatient hospitalizations in the US, with aggregate inpatient hospital costs of $10.4 billion.

Research

Lipids

An indication of the role of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) on atherosclerosis has been with the rare Apo-A1 Milano human genetic variant of this HDL protein. A small short-term trial using bacterial synthesized human Apo-A1 Milano HDL in people with unstable angina produced a fairly dramatic reduction in measured coronary plaque volume in only six weeks vs. the usual increase in plaque volume in those randomized to placebo. The trial was published in JAMA in early 2006. Ongoing work starting in the 1990s may lead to human clinical trials—probably by about 2008. These may use synthesized Apo-A1 Milano HDL directly, or they may use gene-transfer methods to pass the ability to synthesize the Apo-A1 Milano HDLipoprotein.

Methods to increase HDL particle concentrations, which in some animal studies largely reverses and removes atheromas, are being developed and researched. However, increasing HDL by any means is not necessarily helpful. For example, the drug torcetrapib is the most effective agent currently known for raising HDL (by up to 60%). However, in clinical trials, it also raised deaths by 60%. All studies regarding this drug were halted in December 2006.

The actions of macrophages drive atherosclerotic plaque progression. Immunomodulation of atherosclerosis is the term for techniques that modulate immune system function to suppress this macrophage action.

Involvement of lipid peroxidation chain reaction in atherogenesis triggered research on the protective role of the heavy isotope (deuterated) polyunsaturated fatty acids (D-PUFAs) that are less prone to oxidation than ordinary PUFAs (H-PUFAs). PUFAs are essential nutrients – they are involved in metabolism in that very form as they are consumed with food. In transgenic mice, that are a model for human-like lipoprotein metabolism, adding D-PUFAs to diet indeed reduced body weight gain, improved cholesterol handling and reduced atherosclerotic damage to the aorta.

miRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have complementary sequences in the 3' UTR and 5' UTR of target mRNAs of protein-coding genes, and cause mRNA cleavage or repression of translational machinery. In diseased vascular vessels, miRNAs are dysregulated and highly expressed. miR-33 is found in cardiovascular diseases. It is involved in atherosclerotic initiation and progression including lipid metabolism, insulin signaling and glucose homeostatis, cell type progression and proliferation, and myeloid cell differentiation. It was found in rodents that the inhibition of miR-33 will raise HDL level and the expression of miR-33 is down-regulated in humans with atherosclerotic plaques.

miR-33a and miR-33b are located on intron 16 of human sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) gene on chromosome 22 and intron 17 of SREBP1 gene on chromosome 17. miR-33a/b regulates cholesterol/lipid homeostatis by binding in the 3’UTRs of genes involved in cholesterol transport such as ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters and enhance or represses its expression. Study have shown that ABCA1 mediates transport of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to Apolipoprotein-1 and it is also important in the reverse cholesterol transport pathway, where cholesterol is delivered from peripheral tissue to the liver, where it can be excreted into bile or converted to bile acids prior to excretion. Therefore, we know that ABCA1 plays an important role in preventing cholesterol accumulation in macrophages. By enhancing miR-33 function, the level of ABCA1 is decreased, leading to decrease cellular cholesterol efflux to apoA-1. On the other hand, by inhibiting miR-33 function, the level of ABCA1 is increased and increases the cholesterol efflux to apoA-1. Suppression of miR-33 will lead to less cellular cholesterol and higher plasma HDL level through the regulation of ABCA1 expression.

The sugar, cyclodextrin, removed cholesterol that had built up in the arteries of mice fed a high-fat diet.

DNA damage

Aging is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular problems. The causative basis by which aging mediates its impact, independently of other recognized risk factors, remains to be determined. Evidence has been reviewed for a key role of DNA damage in vascular aging. 8-oxoG, a common type of oxidative damage in DNA, is found to accumulate in plaque vascular smooth muscle cells, macrophages and endothelial cells, thus linking DNA damage to plaque formation. DNA strand breaks also increased in atherosclerotic plaques. Werner syndrome (WS) is a premature aging condition in humans. WS is caused by a genetic defect in a RecQ helicase that is employed in several repair processes that remove damages from DNA. WS patients develop a considerable burden of atherosclerotic plaques in their coronary arteries and aorta: calcification of the aortic valve is also frequently observed. These findings link excessive unrepaired DNA damage to premature aging and early atherosclerotic plaque development.

Microorganisms

The microbiota – all the microorganisms in the body, can contribute to atherosclerosis in many ways: modulation of the immune system, changes in metabolism, processing of nutrients and production of certain metabolites that can get into blood circulation. One such metabolite, produced by gut bacteria, is trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Its levels have been associated with atherosclerosis in human studies and animal research suggest that there can be a causal relation. An association between the bacterial genes encoding trimethylamine lyases — the enzymes involved in TMAO generation — and atherosclerosis has been noted.

Vascular smooth muscle cells

Vascular smooth muscle cells play a key role in atherogenesis and were historically considered to be beneficial for plaque stability by forming a protective fibrous cap and synthesising strength-giving extracellular matrix components. However, in addition to the fibrous cap, vascular smooth muscle cells also give rise to many of the cell types found within the plaque core and can modulate their phenotype to both promote and reduce plaque stability. Vascular smooth muscle cells exhibit pronounced plasticity within atherosclerotic plaque and can modify their gene expression profile to resemble various other cell types, including macrophages, myofibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells and osteochondrocytes. Importantly, genetic lineage‐tracing experiments have unequivocally shown that 40-90% of plaque-resident cells are vascular smooth muscle cell derived. Therefore, it is important to research the role of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis to identify new therapeutic targets.