| Part of a series on |

| Revolution |

|---|

|

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society consequent to socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms of class conflict include direct violence such as wars for resources and cheap labor, assassinations or revolution; indirect violence such as deaths from poverty and starvation, illness and unsafe working conditions; and economic coercion such as the threat of unemployment or the withdrawal of investment capital; or ideologically, by way of political literature. Additionally, political forms of class warfare include: legal and illegal lobbying, and bribery of legislators.

The social-class conflict can be direct, as in a dispute between labour and management such as an employer's industrial lockout of their employees in effort to weaken the bargaining power of the corresponding trade union; or indirect such as a workers' slowdown of production in protest of unfair labor practices like low wages and poor workplace conditions.

In the political and economic philosophies of Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin, class struggle is a central tenet and a practical means for effecting radical social and political changes for the social majority.

Usage

In political science, socialists and Marxists use the term class conflict to define a social class by its relationship to the means of production, such as factories, agricultural land, and industrial machinery. The social control of labor and of the production of goods and services, is a political contest between the social classes.

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin said that the class struggles of the working class, the peasantry, and the working poor were central to realizing a social revolution to depose and replace the ruling class, and the creation of libertarian socialism.

Marx's theory of history proposes that class conflict is decisive in the history of economic systems organized by hierarchies of social class such as capitalism and feudalism. Marxists refer to its overt manifestations as class war, a struggle whose resolution in favor of the working class is viewed by them as inevitable under the plutocratic capitalism.

Oligarchs versus commoners

Where societies are socially divided based on status, wealth, or control of social production and distribution, class structures arise and are thus coeval with civilization itself. This has been well documented since at least European classical antiquity such as the Conflict of the Orders and Spartacus, among others.

Thucydides

In his History, Thucydides describes a civil war in the city of Corcyra between the pro-Athens party of the common people and their pro-Corinth oligarchic opposition. Near the climax of the struggle, "the oligarchs in full rout, fearing that the victorious commons might assault and carry the arsenal and put them to the sword, fired the houses round the market-place and the lodging-houses, in order to bar their advance." The historian Tacitus would later recount a similar class conflict in the city of Seleucia, in which disharmony between the oligarchs and the commoners would typically lead to each side calling on outside help to defeat the other. Thucydides believed that "as long as poverty gives men the courage of necessity, [...] so long will the impulse never be wanting to drive men into danger."

Aristotle

In his treatise Politics, Aristotle describes the basic dimensions of class war: "Again, because the rich are generally few in number, while the poor are many, they appear to be antagonistic, and as the one or the other prevails they form the government.". Aristotle also commented that "poverty is the parent of revolution." However, he did not consider this its only cause. In a society where property is distributed equally across the community, "the nobles will be dissatisfied because they think themselves worthy of more than an equal share of honours; and this is often found to be a cause of sedition and revolution." Aristotle thought it wrong for the poor to seize the wealth of the rich and divide it among themselves, but he also thought it wrong for the rich to impoverish the multitude.

Moreover, he discussed what he considered a middle way between laxity and cruelty in the treatment of slaves by their masters, averring that "if not kept in hand, [slaves] are insolent, and think that they are as good as their masters, and, if harshly treated, they hate and conspire against them."

Socrates

Socrates was perhaps the first major Greek philosopher to describe class war. In Plato's Republic, Socrates proposes that "any city, however small, is in fact divided into two, one the city of the poor, the other of the rich; these are at war with one another." Socrates took a poor view of oligarchies, in which members of a small class of wealthy property owners take positions of power in order to dominate a large class of impoverished commoners. He used the analogy of a maritime pilot, who, like a powerholder in a polis, ought to be chosen for his skill, not for the amount of property he owns.

Plutarch

Plutarch recounts how various classical figures took part in class conflict. Oppressed by their indebtedness to the rich, the mass of Athenians chose Solon to be the lawgiver to lead them to freedom from their creditors. Hegel believed that Solon's constitution of the Athenian popular assembly created a political sphere that had the effect of balancing the interests of the three main classes of Athens:

- The wealthy aristocratic party of the plain

- The poorer common party of the mountains

- The moderate party of the coast

Participation in Ancient Greek class war could have dangerous consequences. Plutarch noted of King Agis of Sparta that, "being desirous to raise the people, and to restore the noble and just form of government, now long fallen into disuse, [he] incurred the hatred of the rich and powerful, who could not endure to be deprived of the selfish enjoyment to which they were accustomed."

Patricians versus plebeians

It was similarly difficult for the Romans to maintain peace between the upper class, the patricians, and the lower class, the plebs. French Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu notes that this conflict intensified after the overthrow of the Roman monarchy. In The Spirit of Laws he lists the four main grievances of the plebs, which were rectified in the years following the deposition of King Tarquin:

- The patricians had much too easy access to positions of public service.

- The constitution granted the consuls far too much power.

- The plebs were constantly verbally slighted.

- The plebs had too little power in their assemblies.

Camillus

The Senate had the ability to give a magistrate the power of dictatorship, meaning he could bypass public law in the pursuit of a prescribed mandate. Montesquieu explains that the purpose of this institution was to tilt the balance of power in favour of the patricians. However, in an attempt to resolve a conflict between the patricians and the plebs, the dictator Camillus used his power of dictatorship to coerce the Senate into giving the plebs the right to choose one of the two consuls.

Marius

Tacitus believed that the increase in Roman power spurred the patricians to expand their power over more and more cities. This process, he felt, exacerbated pre-existing class tensions with the plebs, and eventually culminated in the patrician Sulla's first civil war, with the populist reformer Marius. Marius had taken the step of enlisting capite censi, the very lowest class of citizens, into the army, for the first time allowing non-land owners into the legions.

Tiberius Gracchus

Of all the notable figures discussed by Plutarch and Tacitus, agrarian reformer Tiberius Gracchus may have most challenged the upper classes and most championed the cause of the lower classes. In a speech to the common soldiery, he decried their lowly conditions:

"The savage beasts," said he, "in Italy, have their particular dens, they have their places of repose and refuge; but the men who bear arms, and expose their lives for the safety of their country, enjoy in the meantime nothing more in it but the air and light; and having no houses or settlements of their own, are constrained to wander from place to place with their wives and children."

Following this observation, he remarked that these men "fought indeed and were slain, but it was to maintain the luxury and the wealth of other men." Cicero believed that Tiberius Gracchus's reforming efforts saved Rome from tyranny, arguing:

Tiberius Gracchus (says Cicero) caused the free-men to be admitted into the tribes, not by the force of his eloquence, but by a word, by a gesture; which had he not effected, the republic, whose drooping head we are at present scarce able to uphold, would not even exist.

Tiberius Gracchus weakened the power of the Senate by changing the law so that judges were chosen from the ranks of the knights, instead of their social superiors in the senatorial class.

Julius Caesar

Contrary to Shakespeare's depiction of Julius Caesar in the tragedy Julius Caesar, historian Michael Parenti has argued that Caesar was a populist, not a tyrant. In 2003 The New Press published Parenti's The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome. Publisher's Weekly said "Parenti [...] narrates a provocative history of the late republic in Rome (100–33 B.C.) to demonstrate that Caesar's death was the culmination of growing class conflict, economic disparity and political corruption." Kirkus Reviews wrote: "Populist historian Parenti... views ancient Rome’s most famous assassination not as a tyrannicide but as a sanguinary scene in the never-ending drama of class warfare."

Coriolanus

The patrician Coriolanus, whose life William Shakespeare would later depict in the tragic play Coriolanus, fought on the other side of the class war, for the patricians and against the plebs. When grain arrived to relieve a serious shortage in the city of Rome, the plebs made it known that they felt it ought to be divided amongst them as a gift, but Coriolanus stood up in the Senate against this idea on the grounds that it would empower the plebs at the expense of the patricians.

This decision would eventually contribute to Coriolanus's undoing when he was impeached following a trial by the tribunes of the plebs. Montesquieu recounts how Coriolanus castigated the tribunes for trying a patrician, when in his mind no one but a consul had that right, although a law had been passed stipulating that all appeals affecting the life of a citizen had to be brought before the plebs.

In the first scene of Shakespeare's Coriolanus, a crowd of angry plebs gathers in Rome to denounce Coriolanus as the "chief enemy to the people" and "a very dog to the commonalty" while the leader of the mob speaks out against the patricians thusly:

They ne'er cared for us yet: suffer us to famish, and their store-houses crammed with grain; make edicts for usury, to support usurers; repeal daily any wholesome act established against the rich, and provide more piercing statutes daily, to chain up and restrain the poor. If the wars eat us not up, they will; and there's all the love they bear us.

Landlessness and debt

Enlightenment-era historian Edward Gibbon might have agreed with this narrative of Roman class conflict. In the third volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he relates the origins of the struggle:

[T]he plebeians of Rome [...] had been oppressed from the earliest times by the weight of debt and usury; and the husbandman, during the term of his military service, was obliged to abandon the cultivation of his farm. The lands of Italy which had been originally divided among the families of free and indigent proprietors, were insensibly purchased or usurped by the avarice of the nobles; and in the age which preceded the fall of the republic, it was computed that only two thousand citizens were possessed of an independent substance.

Hegel similarly states that the 'severity of the patricians their creditors, the debts due to whom they had to discharge by slave-work, drove the plebs to revolts.' Gibbon also explains how Augustus facilitated this class warfare by pacifying the plebs with actual bread and circuses.

The economist Adam Smith noted that the poor freeman's lack of land provided a major impetus for Roman colonisation, as a way to relieve class tensions at home between the rich and the landless poor. Hegel described the same phenomenon happening in the impetus to Greek colonisation.

Masters versus workmen

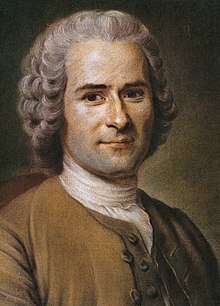

Writing in pre-capitalist Europe, both the Swiss philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Smith made significant remarks on the dynamics of class struggle, as did the Federalist statesman James Madison across the Atlantic Ocean. Later, in the age of early industrial capitalism, English political economist John Stuart Mill and German idealist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel would also contribute their perspectives to the discussion around class conflict between employers and employees.

Rousseau

It was with bitter sarcasm that Rousseau outlined the class conflict prevailing in his day between masters and their workmen:

You have need of me, because I am rich and you are poor. We will therefore come to an agreement. I will permit you to have the honour of serving me, on condition that you bestow on me the little you have left, in return for the pains I shall take to command you.

Rousseau argued that the most important task of any government is to fight in class warfare on the side of workmen against their masters, who he said engage in exploitation under the pretence of serving society. Specifically, he believed that governments should actively intervene in the economy to abolish poverty and prevent the accrual of too much wealth in the hands of too few men.

Adam Smith

Like Rousseau, the classical liberal Adam Smith believed that the amassing of property in the hands of a minority naturally resulted in an disharmonious state of affairs where "the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of many" and "excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade [the rich man's] possessions."

Concerning wages, he explained the conflicting class interests of masters and workmen, who he said were often compelled to form trade unions for fear of suffering starvation wages, as follows:

What are the common wages of labour, depends everywhere upon the contract usually made between those two parties, whose interests are by no means the same. The workmen desire to get as much, the masters to give as little, as possible. The former are disposed to combine in order to raise, the latter in order to lower, the wages of labour.

Smith was aware of the main advantage of masters over workmen, in addition to state protection:

The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily: and the law, besides, authorises, or at least does not prohibit, their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work, but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes, the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, or merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks, which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year, without employment. In the long run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.

Smith observed that, outside of colonies where land is cheap and labour expensive, both the masters who subsist by profit and the masters who subsist by rents will work in tandem to subjugate the class of workmen, who subsist by wages. Moreover, he warned against blindly legislating in favour of the class of masters who subsist by profit, since, as he said, their intention is to gain as large a share of their respective markets as possible, which naturally results in monopoly prices or close to them, a situation harmful to the other social classes.

James Madison

In his Federalist No. 10, James Madison revealed an emphatic concern with the conflict between rich and poor, commenting that "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination." He welcomed class-based factions into political life as a necessary result of political liberty, stating that the most important task of government was to manage and adjust for 'the spirit of party'.

John Stuart Mill

Adam Smith was not the only classical liberal political economist concerned with class conflict. In his Considerations on Representative Government, John Stuart Mill observed the complete marginalisation of workmen's voices in Parliament, rhetorically asking whether its members ever empathise with the position of workmen, instead of siding entirely with their masters, on issues such as the right to go on strike. Later in the book, he argues that an important function of truly representative government is to provide a relatively equal balance of power between workmen and masters, in order to prevent threats to the good of the whole of society.

During Mill's discussion of the merits of progressive taxation in his essay Utilitarianism, he notes as an aside the power of the rich as independent of state support:

People feel obliged to argue that the State does more for the rich than for the poor, as a justification for its taking more [in taxation] from them: though this is in reality not true, for the rich would be far better able to protect themselves, in the absence of law or government, than the poor, and indeed would probably be successful in converting the poor into their slaves.

Hegel

In his Philosophy of Right, Hegel expressed concern that the standard of living of the poor might drop so far as to make it even easier for the rich to amass even more wealth. Hegel believed that, especially in a liberal country such as contemporary England, the poorest will politicise their situation, channelling their frustrations against the rich:

Against nature man can claim no right, but once society is established, poverty immediately takes the form of a wrong done to one class by another.

Capitalist societies

The typical example of class conflict described is class conflict within capitalism. This class conflict is seen to occur primarily between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and takes the form of conflict over hours of work, value of wages, division of profits, cost of consumer goods, the culture at work, control over parliament or bureaucracy, and economic inequality. The particular implementation of government programs which may seem purely humanitarian, such as disaster relief, can actually be a form of class conflict.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) led the U.S. as president from 1801 to 1809 and is considered one of the founding fathers. Regarding the interaction between social classes, he wrote:

I am convinced that those societies (as the Indians) which live without government enjoy in their general mass an infinitely greater degree of happiness than those who live under the European governments. Among the former, public opinion is in the place of law, & restrains morals as powerfully as laws ever did anywhere. Among the latter, under pretence of governing they have divided their nations into two classes, wolves & sheep. I do not exaggerate. This is a true picture of Europe. Cherish therefore the spirit of our people, and keep alive their attention. Do not be too severe upon their errors, but reclaim them by enlightening them. If once they become inattentive to the public affairs, you & I, & Congress & Assemblies, judges & governors shall all become wolves. It seems to be the law of our general nature, in spite of individual exceptions; and experience declares that man is the only animal which devours his own kind, for I can apply no milder term to the governments of Europe, and to the general prey of the rich on the poor.

— Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Edward Carrington - 16 January 1787

Max Weber

Max Weber (1864–1920) agreed with the fundamental ideas of Karl Marx about the economy causing class conflict, but claimed that class conflict can also stem from prestige and power. Weber argued that classes come from the different property locations. Different locations can largely affect one's class by their education and the people they associate with. He also stated that prestige results in different status groupings. This prestige is based upon the social status of one's parents. Prestige is an attributed value and many times cannot be changed. Weber stated that power differences led to the formation of political parties. Weber disagreed with Marx about the formation of classes. While Marx believed that groups are similar due to their economic status, Weber argued that classes are largely formed by social status. Weber did not believe that communities are formed by economic standing, but by similar social prestige. Weber did recognize that there is a relationship between social status, social prestige and classes.

Twentieth century

In the U.S., class conflict is often noted in labor/management disputes. As far back as 1933 representative Edward Hamilton of the Airline Pilot's Association, used the term "class warfare" to describe airline management's opposition at the National Labor Board hearings in October of that year. Apart from these day-to-day forms of class conflict, during periods of crisis or revolution class conflict takes on a violent nature and involves repression, assault, restriction of civil liberties, and murderous violence such as assassinations or death squads.

Twenty-first century

Financial crisis

Class conflict intensified in the period after the 2007/8 financial crisis, which led to a global wave of anti-austerity protests, including the Greek and Spanish Indignados movements and later the Occupy movement, whose slogan was "We are the 99%", signalling a more expansive class antagonist against the financial elite than that of the classical Marxist proletariat.

The investor, billionaire, and philanthropist Warren Buffett, one of the wealthiest people in the world, voiced in 2005 and once more in 2006 his view that his class, the "rich class", is waging class warfare on the rest of society. In 2005 Buffet said to CNN: "It's class warfare, my class is winning, but they shouldn't be." In a November 2006 interview in The New York Times, Buffett stated that "[t]here’s class warfare all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning."

In the speech "The Great American Class War" (2013), the journalist Bill Moyers asserted the existence of social-class conflict between democracy and plutocracy in the U.S. Chris Hedges wrote a column for Truthdig called "Let's Get This Class War Started", which was a play on Pink's song "Let's Get This Party Started."

Historian Steve Fraser, author of The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power, asserted in 2014 that class conflict is an inevitability if current political and economic conditions continue, noting that "people are increasingly fed up [...] their voices are not being heard. And I think that can only go on for so long without there being more and more outbreaks of what used to be called class struggle, class warfare."

Arab Spring

Often seen as part of the same "movement of squares" as the Indignado and Occupy movements, the Arab Spring was a wave of social protests starting in 2011. Numerous factors have culminated in the Arab Spring, including rejection of dictatorship or absolute monarchy, human rights violations, government corruption (demonstrated by Wikileaks diplomatic cables), economic decline, unemployment, extreme poverty, and a number of demographic structural factors, such as a large percentage of educated but dissatisfied youth within the population. but class conflict is also a key factor. The catalysts for the revolts in all Northern African and Persian Gulf countries have been the concentration of wealth in the hands of autocrats in power for decades, insufficient transparency of its redistribution, corruption, and especially the refusal of the youth to accept the status quo.

Socialism

Marxist perspectives

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German born philosopher who lived the majority of his adult life in London, England. In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx argued that a class is formed when its members achieve class consciousness and solidarity. This largely happens when the members of a class become aware of their exploitation and the conflict with another class. A class will then realize their shared interests and a common identity. According to Marx, a class will then take action against those that are exploiting the lower classes.

What Marx points out is that members of each of the two main classes have interests in common. These class or collective interests are in conflict with those of the other class as a whole. This in turn leads to conflict between individual members of different classes.

Marxist analysis of society identifies two main social groups:

- Labour (the proletariat or workers) includes anyone who earns their livelihood by selling their labor power and being paid a wage or salary for their labor time. They have little choice but to work for capital, since they typically have no independent way to survive.

- Capital (the bourgeoisie or capitalists) includes anyone who gets their income not from labor as much as from the surplus value they appropriate from the workers who create wealth. The income of the capitalists, therefore, is based on their exploitation of the workers (proletariat).

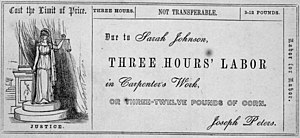

Not all class struggle is violent or necessarily radical, as with strikes and lockouts. Class antagonism may instead be expressed as low worker morale, minor sabotage and pilferage, and individual workers' abuse of petty authority and hoarding of information. It may also be expressed on a larger scale by support for socialist or populist parties. On the employers' side, the use of union busting legal firms and the lobbying for anti-union laws are forms of class struggle.

Not all class struggle is a threat to capitalism, or even to the authority of an individual capitalist. A narrow struggle for higher wages by a small sector of the working-class, what is often called "economism", hardly threatens the status quo. In fact, by applying the craft-union tactics of excluding other workers from skilled trades, an economistic struggle may even weaken the working class as a whole by dividing it. Class struggle becomes more important in the historical process as it becomes more general, as industries are organized rather than crafts, as workers' class consciousness rises, and as they self-organize away from political parties. Marx referred to this as the progress of the proletariat from being a class "in itself", a position in the social structure, to being one "for itself", an active and conscious force that could change the world.

Marx largely focuses on the capital industrialist society as the source of social stratification, which ultimately results in class conflict. He states that capitalism creates a division between classes which can largely be seen in manufacturing factories. The proletariat, is separated from the bourgeoisie because production becomes a social enterprise. Contributing to their separation is the technology that is in factories. Technology de-skills and alienates workers as they are no longer viewed as having a specialized skill. Another effect of technology is a homogenous workforce that can be easily replaceable. Marx believed that this class conflict would result in the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and that the private property would be communally owned. The mode of production would remain, but communal ownership would eliminate class conflict.

Even after a revolution, the two classes would struggle, but eventually the struggle would recede and the classes dissolve. As class boundaries broke down, the state apparatus would wither away. According to Marx, the main task of any state apparatus is to uphold the power of the ruling class; but without any classes there would be no need for a state. That would lead to the classless, stateless communist society.

Soviet Union and similar societies

A variety of predominantly Trotskyist and anarchist thinkers argue that class conflict existed in Soviet-style societies. Their arguments describe as a class the bureaucratic stratum formed by the ruling political party (known as the nomenklatura in the Soviet Union), sometimes termed a "new class", that controls and guides the means of production. This ruling class is viewed to be in opposition to the remainder of society, generally considered the proletariat. This type of system is referred by them as state socialism, state capitalism, bureaucratic collectivism or new class societies. Marxism was such a predominate ideological power in what became the Soviet Union since a Marxist group known as the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was formed in the country, prior to 1917. This party soon divided into two main factions; the Bolsheviks, who were led by Vladimir Lenin, and the Mensheviks, who were led by Julius Martov.

However, many Marxist argue that unlike in capitalism the Soviet elites did not own the means of production, or generated surplus value for their personal wealth like in capitalism as the generated profit from the economy was equally distributed into Soviet society. Even some Trotskyist like Ernest Mandel criticized the concept of a new ruling class as an oxymoron, saying: "The hypothesis of the bureaucracy’s being a new ruling class leads to the conclusion that, for the first time in history, we are confronted with a 'ruling class' which does not exist as a class before it actually rules."

Non-Marxist perspectives

One of the first writers to comment on class struggle in the modern sense of the term was the French revolutionary François Boissel. Other class struggle commentators include Henri de Saint-Simon, Augustin Thierry, François Guizot, François-Auguste Mignet and Adolphe Thiers. The Physiocrats, David Ricardo, and after Marx, Henry George noted the inelastic supply of land and argued that this created certain privileges (economic rent) for landowners. According to the historian Arnold J. Toynbee, stratification along lines of class appears only within civilizations, and furthermore only appears during the process of a civilization's decline while not characterizing the growth phase of a civilization.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in What is Property? (1840) states that "certain classes do not relish investigation into the pretended titles to property, and its fabulous and perhaps scandalous history." While Proudhon saw the solution as the lower classes forming an alternative, solidarity economy centered on cooperatives and self-managed workplaces, which would slowly undermine and replace capitalist class society, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, while influenced by Proudhon, insisted that a massive class struggle by the working class, peasantry and poor was essential to the creation of libertarian socialism. This would require a final showdown in the form of a social revolution.

One of the earliest analyses of the development of class as the development of conflicts between emergent classes is available in Peter Kropotkin's Mutual Aid. In this work, Kropotkin analyzes the disposal of goods after death in pre-class or hunter-gatherer societies, and how inheritance produces early class divisions and conflict.

Fascists have often opposed 'horizontal' class struggle in favour of vertical national struggle and instead have attempted to appeal to the working class while promising to preserve the existing social classes and have proposed an alternative concept known as class collaboration.

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky, American linguist, philosopher, and political activist has criticized class war in the United States:

Well, there’s always a class war going on. The United States, to an unusual extent, is a business-run society, more so than others. The business classes are very class-conscious—they’re constantly fighting a bitter class war to improve their power and diminish opposition. Occasionally this is recognized... The enormous benefits given to the very wealthy, the privileges for the very wealthy here, are way beyond those of other comparable societies and are part of the ongoing class war. Take a look at CEO salaries....

— Noam Chomsky, OCCUPY: Class War, Rebellion and Solidarity, Second Edition (November 5, 2013)

Rightwing libertarianism

Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer argued that class struggle came from factions that managed to gain control of the State power. The ruling class are the groups that seize the power of the State to carry out their political agenda, the ruled are then taxed and regulated by the State for the benefit of the Ruling classes. Through taxation, State power, subsidies, Tax codes, laws, and privileges the State creates class conflict by giving preferential treatment to some at the expense of others by force. In the free market, by contrast, exchanges are not carried out by force but by the Non-aggression principle of cooperation in a Win-win scenario.

Relationship to race

Some historical tendencies of Orthodox Marxism reject racism, sexism, etc. as struggles that essentially distract from class struggle, the real conflict.[citation needed] These divisions within the class prevent the purported antagonists from acting in their common class interest. However, many Marxist internationalists and anti-colonial revolutionaries believe that sex, race and class are bound up together. Within Marxist scholarship there is an ongoing debate about these topics.

According to Michel Foucault, in the 19th century, the essentialist notion of the "race" was incorporated by racists, biologists, and eugenicists, who gave it the modern sense of "biological race" which was then integrated into "state racism". On the other hand, Foucault claims that when Marxists developed their concept of "class struggle", they were partly inspired by the older, non-biological notions of the "race" and the "race struggle". Quoting a non-existent 1882 letter from Marx to Friedrich Engels during a lecture, Foucault erroneously claimed Marx wrote: "You know very well where we found our idea of class struggle; we found it in the work of the French historians who talked about the race struggle."[76][citation needed] For Foucault, the theme of social war provides the overriding principle that connects class and race struggle.

Moses Hess, an important theoretician and labor Zionist of the early socialist movement, in his "Epilogue" to "Rome and Jerusalem" argued that "the race struggle is primary, the class struggle secondary. [...] With the cessation of race antagonism, the class struggle will also come to a standstill. The equalization of all classes of society will necessarily follow the emancipation of all the races, for it will ultimately become a scientific question of social economics."

W. E. B. Du Bois theorized that the intersectional paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain certain aspects of black political economy. Patricia Hill Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."

In modern times, emerging schools of thought in the U.S. and other countries hold the opposite to be true. They argue that the race struggle is less important, because the primary struggle is that of class since labor of all races face the same problems and injustices.