Hydrogen storage is a term used for any of several methods for storing hydrogen for later use. These methods encompass mechanical approaches such as high pressures and low temperatures, or chemical compounds that release H2 upon demand. While large amounts of hydrogen are produced, it is mostly consumed at the site of production, notably for the synthesis of ammonia. For many years hydrogen has been stored as compressed gas or cryogenic liquid, and transported as such in cylinders, tubes, and cryogenic tanks for use in industry or as propellant in space programs. Interest in using hydrogen for on-board storage of energy in zero-emissions vehicles is motivating the development of new methods of storage, more adapted to this new application. The overarching challenge is the very low boiling point of H2: it boils around 20.268 K (−252.882 °C or −423.188 °F). Achieving such low temperatures requires significant energy.

Established technologies

Compressed hydrogen

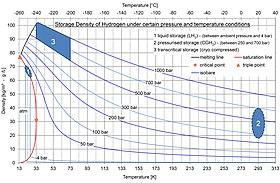

Compressed hydrogen is a storage form whereby hydrogen gas is kept under pressures to increase the storage density. Compressed hydrogen in hydrogen tanks at 350 bar (5,000 psi) and 700 bar (10,000 psi) is used for hydrogen tank systems in vehicles, based on type IV carbon-composite technology. Car manufacturers have been developing this solution, such as Honda or Nissan.

Liquefied hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen tanks for cars, producing for example the BMW Hydrogen 7. Japan has a liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage site in Kobe port. Hydrogen is liquefied by reducing its temperature to −253 °C, similar to liquefied natural gas (LNG) which is stored at −162 °C. A potential efficiency loss of only 12.79% can be achieved, or 4.26 kW⋅h/kg out of 33.3 kW⋅h/kg.

Chemical storage

Chemical storage could offer high storage performance due to the high storage densities. For example, supercritical hydrogen at 30 °C and 500 bar only has a density of 15.0 mol/L while methanol has a density of 49.5 mol H2/L methanol and saturated dimethyl ether at 30 °C and 7 bar has a density of 42.1 mol H2/L dimethyl ether.

Regeneration of storage material is problematic. A large number of chemical storage systems have been investigated. H2 release can be induced by hydrolysis reactions or catalyzed dehydrogenation reactions. Illustrative storage compounds are hydrocarbons, boron hydrides, ammonia, and alane etc. A most promising chemical approach is electrochemical hydrogen storage, as the release of hydrogen can be controlled by the applied electricity. Most of the materials listed below can be directly used for electrochemical hydrogen storage.

As shown before, nanomaterials offer advantage for hydrogen storage systems. Nanomaterials offer an alternative that overcomes the two major barriers of bulk materials, rate of sorption and release temperature.

Enhancement of sorption kinetics and storage capacity can be improved through nanomaterial-based catalyst doping, as shown in the work of the Clean Energy Research Center in the University of South Florida. This research group studied LiBH4 doped with nickel nanoparticles and analyzed the weight loss and release temperature of the different species. They observed that an increasing amount of nanocatalyst lowers the release temperature by approximately 20 °C and increases the weight loss of the material by 2-3%. The optimum amount of Ni particles was found to be 3 mol%, for which the temperature was within the limits established (around 100 °C) and the weight loss was notably greater than the undoped species.

The rate of hydrogen sorption improves at the nanoscale due to the short diffusion distance in comparison to bulk materials. They also have favorable surface-area-to-volume ratio.

The release temperature of a material is defined as the temperature at which the desorption process begins. The energy or temperature to induce release affects the cost of any chemical storage strategy. If the hydrogen is bound too weakly, the pressure needed for regeneration is high, thereby cancelling any energy savings. The target for onboard hydrogen fuel systems is roughly <100 °C for release and <700 bar for recharge (20–60 kJ/mol H2). A modified van ’t Hoff equation, relates temperature and partial pressure of hydrogen during the desorption process. The modifications to the standard equation are related to size effects at the nanoscale.

Where pH2 is the partial pressure of hydrogen, ΔH is the enthalpy of the sorption process (exothermic), ΔS is the change in entropy, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, Vm is the molar volume of the metal, r is the radius of the nanoparticle and γ is the surface free energy of the particle.

From the above relation we see that the enthalpy and entropy change of desorption processes depend on the radius of the nanoparticle. Moreover, a new term is included that takes into account the specific surface area of the particle and it can be mathematically proven that a decrease in particle radius leads to a decrease in the release temperature for a given partial pressure.

Hydrogenation of CO2

The CO2 emission is causing an unclouded carbon cycle. The climate change and related issue requires immediate attention. Current approach to reduce CO2 includes capturing and storing from facilities across the world. However, storage posts technical and economic barriers preventing global scale application.To utilize CO2 at the point source, CO2 hydrogenation is a realistic and practical approach. Conventional hydrogenation reduces saturated organic compounds by addition of H2. One pathway of CO2 hydrogenation is CO2 to methanol pathway. Methanol can be used to produce long chain hydrocarbons. Some barriers of CO2 hydrogenation includes purification of captured CO2, H2 source from splitting water and energy inputs for hydrogenation. To overcome these barriers, we can further develop green H2 technology and encourage catalyst research at industrial and academic level. For industrial applications, CO2 is often converted to methanol. Till now, much progress has been made for CO2 to C1 molecules. However, CO2 to high value molecules still face many roadblocks and the future of CO2 hydrogenation depends on the advancement of catalytic technologies.

Metal hydrides

Metal hydrides, such as MgH2, NaAlH4, LiAlH4, LiH, LaNi5H6, TiFeH2, ammonia borane, and palladium hydride represent sources of stored hydrogen. Again the persistent problems are the % weight of H2 that they carry and the reversibility of the storage process. Some are easy-to-fuel liquids at ambient temperature and pressure, whereas others are solids which could be turned into pellets. These materials have good energy density, although their specific energy is often worse than the leading hydrocarbon fuels.

An alternative method for lowering dissociation temperatures is doping with activators. This strategy has been used for aluminium hydride, but the complex synthesis makes the approach unattractive.

Proposed hydrides for use in a hydrogen economy include simple hydrides of magnesium or transition metals and complex metal hydrides, typically containing sodium, lithium, or calcium and aluminium or boron. Hydrides chosen for storage applications provide low reactivity (high safety) and high hydrogen storage densities. Leading candidates are lithium hydride, sodium borohydride, lithium aluminium hydride and ammonia borane. A French company McPhy Energy is developing the first industrial product, based on magnesium hydride, already sold to some major clients such as Iwatani and ENEL.

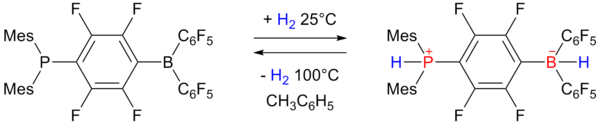

Reversible hydrogen storage is exhibited by frustrated Lewis pair, which produces a borohydride.

The phosphino-borane on the left accepts one equivalent of hydrogen at one atmosphere and 25 °C and expels it again by heating to 100 °C. The storage capacity is 0.25 wt%.

Aluminium

Hydrogen can be produced using aluminium by reacting it with water. To react with water, however, aluminium must be stripped of its natural oxide layer, a process which requires pulverization, chemical reactions with caustic substances, or alloys. The byproduct of the reaction to create hydrogen is aluminum oxide, which can be recycled back into aluminium with the Hall–Héroult process, making the reaction theoretically renewable. However, this requires electrolysis, which consumes a large amount of energy

Magnesium

Mg-based hydrogen storage materials can be generally fell into three categories, i.e., pure Mg, Mg-based alloys, and Mg-based composites. Particularly, more than 300 sorts of Mg-based hydrogen storage alloys have been receiving extensive attention because of the relatively better overall performance. Nonetheless, the inferior hydrogen absorption/desorption kinetics rooting in the overly undue thermodynamic stability of metal hydride make the Mg-based hydrogen storage alloys currently not appropriate for the real applications, and therefore, massive attempts have been dedicated to overcoming these shortages. Some sample preparation methods, such as smelting, powder sintering, diffusion, mechanical alloying, hydriding combustion synthesis method, surface treatment, and heat treatment, etc., have been broadly employed for altering the dynamic performance and cycle life of Mg-based hydrogen storage alloys. Besides, some intrinsic modification strategies, including alloying, nanostructuring, doping by catalytic additives, and acquiring nanocomposites with other hydrides, etc., have been mainly explored for intrinsically boosting the performance of Mg-based hydrogen storage alloys.

Of the primary hydrogen storage alloys progressed formerly, Mg and Mg-based hydrogen storage materials are believed to provide the remarkable possibility of the practical application, on account of the advantages as following: 1) the resource of Mg is plentiful and economical. Mg element exists abundantly and accounts for ~2.35% of the earth’s crust with the rank ofthe eighth; 2) low density ofmerely 1.74 g cm-3; 3) superior hydrogen storage capacity. The theoretical hydrogen storage amounts of the pure Mg is 7.6 wt % (weight percent), and the Mg2Ni is 3.6 wt%, respectively.

Alanates Based-Systems

Sodium Alanate(NaAlH4) is a complex hydride for H2 storage.The crystal structure was first determined through a single crystal X-ray diffracrion study in 1979. The atomic structure consisted of isolated [AlH4]− tetrahedra in which the Na atoms are surrounded by eight [AlH4]− tetrahedra in a distorted square. Hydrogen release from NaAlH4 is known since the 1950's. In 1997, Bogdanovic discovered that Tio2 doping of materials makes the process reversible at modest temperature and pressure. TiO2-doped materials are reversible in hydrogen storage, NaAlH4 is currently the state of the art reversible solid state hydrogen storage material which can be used in low temperature and has 5.6 wt.% hydrogen contained. The chemical reaction is, 3NaAlH4 ← catalyst → Na3AlH6 + 2Al + 3H2 ← catalyst → 3NaH + Al + 3/2H2. The heat required to change from NaAlH4 to Na3AlH6 is 37 kJ/mol. The heat required to change from Na3AlH6 to NaH is 47 kJ/mol. In principle, the first step of NaAlH4 releases 3.7 wt.% hydrogen at about 190 °C and the second step releases 1.8 wt.% hydrogen at about 225 °C upon heating. Further dehydrogenation of NaH occurs only at temperature higher than 400 °C. This temperature is too high for technical applications, therefore, can not be used in a fuel cell vehicle.

Lithium alanate (LiAlH4) was synthesized for the first time in 1947 by dissolution of lithium hydride in an ether solution of aluminium chloride. LiAlH4 has a theoretical gravimetric capacity of 10.5 wt %H2 and dehydrogenates in the following three steps: 3LiAlH4 ↔ Li3AlH6 + 3H2 + 2Al (423–448 K; 5.3 wt %H2; ∆H = −10 kJ·mol−1 H2); Li3AlH6 ↔ 3LiH + Al + 3/2H2 (453–493 K; 2.6 wt %H2; ∆H = 25 kJ·mol−1 H2); 3LiH + 3Al ↔ 3LiAl + 3/2H2 (>673 K; 2.6 wt %H2; ∆H = 140 kJ·mol−1 H2). The first two steps lead to a total amount of hydrogen released equal to 7.9 wt %, which could be attractive for practical applications, but the working temperatures and the desorption kinetics are still far from the practical targets. Several strategies have been applied in the last few years to overcome these limits, such as ball-milling and catalysts additions.

Potassium Alanate (KAlH4) was first prepared by Ashby et al. by one-step synthesis in toluene, tetrahydrofuran, and diglyme. Concerning the hydrogen absorption and desorption properties, this alanate was only scarcely studied. Morioka et al., by temperature programmed desorption (TPD) analyses, proposed the following dehydrogenation mechanism: 3KAlH4 →K3AlH6 + 2Al + 3H2 (573 K, ∆H = 55 kJ·mol−1 H2; 2.9 wt %H2), K3AlH6 → 3KH + Al + 3/2H2 (613 K, ∆H = 70 kJ·mol−1 H2; 1.4 wt %H2), 3KH → 3K + 3/2H2 (703 K, 1.4 wt %H2). These reactions were demonstrated reversible without catalysts addition at relatively low hydrogen pressure and temperatures. The addition of TiCl3 was found to decrease the working temperature of the first dehydrogenation step of 50 K, but no variations were recorded for the last two reaction steps.

Organic hydrogen carriers

Unsaturated organic compounds can store huge amounts of hydrogen. These Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHC) are hydrogenated for storage and dehydrogenated again when the energy/hydrogen is needed. Using LOHCs relatively high gravimetric storage densities can be reached (about 6 wt-%) and the overall energy efficiency is higher than for other chemical storage options such as producing methane from the hydrogen. Both hydrogenation and dehydrogenation of LOHCs requires catalysts. It was demonstrated that replacing hydrocarbons by hetero-atoms, like N, O etc. improves reversible de/hydrogenation properties.

Cycloalkanes

Research on LOHC was concentrated on cycloalkanes at an early stage, with its relatively high hydrogen capacity (6-8 wt %) and production of COx-free hydrogen. Heterocyclic aromatic compounds (or N-Heterocycles) are also appropriate for this task. A compound featuring in LOHC research is N-Ethylcarbazole [de] (NEC) but many others do exist. Dibenzyltoluene, which is already used as a heat transfer fluid in industry, was identified as potential LOHC. With a wide liquid range between -39 °C (melting point) and 390 °C (boiling point) and a hydrogen storage density of 6.2 wt% dibenzyltoluene is ideally suited as LOHC material. Formic acid has been suggested as a promising hydrogen storage material with a 4.4wt% hydrogen capacity.

Cycloalkanes reported as LOHC include cyclohexane, methyl-cyclohexane and decalin. The dehydrogenation of cycloalkanes is highly endothermic (63-69 kJ/mol H2), which means this process requires high temperature. Dehydrogenation of decalin is the most thermodynamically favored among the three cycloalkanes, and methyl-cyclohexane is second because of the presence of the methyl group. Research on catalyst development for dehydrogenation of cycloalkanes has been carried out for decades. Nickel (Ni), Molybdenum (Mo) and Platinum (Pt) based catalysts are highly investigated for dehydrogenation. However, coking is still a big challenge for catalyst's long-term stability.

The addition of second metal such as W,Ir, Re, Rh and Pd etc. and/or promoter (such as Ca) and selection of suitable support (such as CNF and Al2O3) are effective against coking. For cyclohexane, there are two dehydrogenation mechanisms, the sextet mechanism and the doublet mechanism. The difference between the two mechanisms lies in whether they are intermediate products during dehydrogenation. In the sextet mechanism, cyclohexane overlies on the catalyst surface and undergoes dehydrogenation directly to benxzene. In contrast, in the double mechanism, hydrogen will be released step by step because of the C=C double bound.

N-Heterocycles

The temperature required for hydrogenation and dehydrogenation drops significantly for heterocycles vs simple carbocycles. Among all the N-heterocycles, the saturated-unsaturated pair of dodecahydro-N-ethylcarbazole (12H-NEC) and NEC has been considered as a promising candidate for hydrogen storage with a fairly large hydrogen content (5.8wt%). The figure on the top right shows dehydrogenation and hydrogenation of the 12H-NEC and NEC pair. The standard catalyst for NEC to 12H-NEC is Ru and Rh based. The selectivity of hydrogenation can reach 97% at 7 MPa and 130 °C-150 °C. Although N-Heterocyles can optimize the unfavorable thermodynamic properties of cycloalkanes, a lot of issues remain unsolved, such as high cost, high toxicity and kinetic barriers etc.

The imidazolium ionic liquids such alkyl(aryl)-3-methylimidazolium N-bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imidate salts can reversibly add 6–12 hydrogen atoms in the presence of classical Pd/C or Ir0 nanoparticle catalysts and can be used as alternative materials for on-board hydrogen-storage devices. These salts can hold up to 30 g L−1 of hydrogen at atmospheric pressure.

Formic acid

Formic acid is a highly effective hydrogen storage material, although its H2 density is low. Carbon monoxide free hydrogen has been generated in a very wide pressure range (1–600 bar). A homogeneous catalytic system based on water-soluble ruthenium catalysts selectively decompose HCOOH into H2 and CO2 in aqueous solution. This catalytic system overcomes the limitations of other catalysts (e.g. poor stability, limited catalytic lifetimes, formation of CO) for the decomposition of formic acid making it a viable hydrogen storage material. And the co-product of this decomposition, carbon dioxide, can be used as hydrogen vector by hydrogenating it back to formic acid in a second step. The catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 has long been studied and efficient procedures have been developed. Formic acid contains 53 g L−1 hydrogen at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. By weight, pure formic acid stores 4.3 wt% hydrogen. Pure formic acid is a liquid with a flash point 69 °C (cf. gasoline −40 °C, ethanol 13 °C). 85% formic acid is not flammable.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates (polymeric C6H10O5) release H2 in a bioreformer mediated by the enzyme cocktail—cell-free synthetic pathway biotransformation. Carbohydrate provides high hydrogen storage densities as a liquid with mild pressurization and cryogenic constraints: It can also be stored as a solid powder. Carbohydrate is the most abundant renewable bioresource in the world.

Polysaccharides(C6H10O5) has a reaction of C6H10O5 + 7H2O → 12H2 +6CO2. As a result, hydrogen storage density in polysaccharides is 14.8 mass%. Carbonhydrates are much less costly than other carriers. Hydrogen generation from carbonhydrates can be implemented at mild conditions of 30~80 °C and about 1 atm, the process does not need any costly high pressure reactor, and high purity hydrogen mixed with CO2 is generated, making extra product purification unnecessary. Under the mild reaction conditions, separation of gaseous products and aqueous reaction is easy and nearly no cost. Moreover, renewable corbonhydrates are nearly inflammable and not toxic at all. Carbonhydrates may be an appealing hydrogen carrier.

Compared to other hydrogen carriers, carbonhydrates are very appealing due to their low cost, renewable source, high purity hydrogen generated, and so on.

Ammonia

Ammonia (NH3) releases H2 in an appropriate catalytic reformer. Ammonia provides high hydrogen storage densities as a liquid with mild pressurization and cryogenic constraints: It can also be stored as a liquid at room temperature and pressure when mixed with water. Ammonia is the second most commonly produced chemical in the world and a large infrastructure for making, transporting, and distributing ammonia exists. Ammonia can be reformed to produce hydrogen with no harmful waste, or can mix with existing fuels and under the right conditions burn efficiently. Since there is no carbon in ammonia, no carbon by-products are produced; thereby making this possibility a "carbon neutral" option for the future. Pure ammonia burns poorly at the atmospheric pressures found in natural gas fired water heaters and stoves. Under compression in an automobile engine it is a suitable fuel for slightly modified gasoline engines. Ammonia is a suitable alternative fuel because it has 18.6 MJ/kg energy density at NTP and carbon-free combustion byproducts.

Ammonia has several challenges to widespread adaption as a hydrogen storage material. Ammonia is a toxic gas with a potent odor at standard temperature and pressure. Additionally, advances in the efficiency and scalability of ammonia decomposition are needed for commercial viability, as fuel cell membranes are highly sensitive to residual ammonia and current decomposition techniques have low yield rates. A variety of transition metals can be used to catalyze the ammonia decomposition reaction, the most effective being ruthenium. This catalysis works through chemisorption, where the adsorption energy of N2 is less than the reaction energy of dissociation. Hydrogen purification can be achieved in several ways. Hydrogen can be separated from unreacted ammonia using a permeable, hydrogen-selective membrane. It can also be purified through the adsorption of ammonia, which can be selectively trapped due to its polarity.

In September 2005 chemists from the Technical University of Denmark announced a method of storing hydrogen in the form of ammonia saturated into a salt tablet. They claim it will be an inexpensive and safe storage method.

positive and negative attributes of Ammonia ·pro's:High theoretical energy density, Wide spread availability, Large scale commercial production, Benign decomposition pathway to H2 and N2 ·con's:Toxicity, Corrosive, High decomposition temperature leading to efficiency loss

Hydrazine

Hydrazine breaks down in the cell to form nitrogen and hydrogen Silicon hydrides and germanium hydrides are also candidates of hydrogen storage materials, as they can subject to energetically favored reaction to form covalently bonded dimers with loss of a hydrogen molecule.

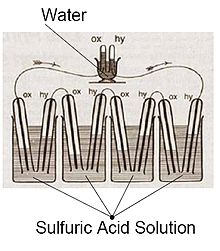

Chemical hydrides

Chemical hydride is a irreversible hydrogen storage material. The reaction of hydrogen releasing from chemical hydrides are usually exothermic, which makes regeneration of the fuel energy-intensive. NaBH4 + 2H2O → NaBO2 + 4H2 + 300 kJ. The chemical reaction gives potential for high density storage, but current systems produce much lower effective density. The NaBH4 has a theoritical effective density of 10.8 wt.%, however there is only 1.1 wt.% of effective density in reality. Examples of chemical hydride reactions: NaBH4 (20~35% solution, stabilized with 1~3% NaOH) + 2H2O (from fuel cell exhaust) → NaBO2 (Borax in NaOH) + 4H2. 2LiH + 2H2O → 2LiOH + 2H2.

A leading chemical hydride is NH3BH3, which is a waxy solid at room temperature with a melting point of 90 °C. Hydrogen will be released from NH3BH3 around 90 °C because of thermal decomposition. NH3BH3 is a promising material for hydrogen storing because it has one of the highest theoretical hydrogen weight percentages at 19.6% and also the highest hydrogen volume density at 151 kg H2 per volume. Hydrogen release from NH3BH3 occurs stepwise, where the onset temperature for the first equivalent is 90 °C, the temperature for second equivalent is 150 °C. The remaining hydrogen will be released at the temperature higher than 150 °C.

Amine boranes

Prior to 1980, several compounds were investigated for hydrogen storage including complex borohydrides, or aluminohydrides, and ammonium salts. These hydrides have an upper theoretical hydrogen yield limited to about 8.5% by weight. Amongst the compounds that contain only B, N, and H (both positive and negative ions), representative examples include: amine boranes, boron hydride ammoniates, hydrazine-borane complexes, and ammonium octahydrotriborates or tetrahydroborates. Of these, amine boranes (and especially ammonia borane) have been extensively investigated as hydrogen carriers. During the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. Army and Navy funded efforts aimed at developing hydrogen/deuterium gas-generating compounds for use in the HF/DF and HCl chemical lasers, and gas dynamic lasers. Earlier hydrogen gas-generating formulations used amine boranes and their derivatives. Ignition of the amine borane(s) forms boron nitride (BN) and hydrogen gas. In addition to ammonia borane (H3BNH3), other gas-generators include diborane diammoniate, H2B(NH3)2BH4.

Physical storage

In this case hydrogen remains in physical forms, i.e., as gas, supercritical fluid, adsorbate, or molecular inclusions. Theoretical limitations and experimental results are considered concerning the volumetric and gravimetric capacity of glass microvessels, microporous, and nanoporous media, as well as safety and refilling-time demands.

Porous or layered carbon

Activated carbons are highly porous amorphous carbon materials with high apparent surface area. Hydrogen physisorption can be increased in these materials by increasing the apparent surface area and optimizing pore diameter to around 7 Å. These materials are of particular interest due to the fact that they can be made from waste materials, such as cigarette butts which have shown great potential as precursor materials for high-capacity hydrogen storage materials.

Graphene can store hydrogen efficiently. The H2 adds to the double bonds giving graphane. The hydrogen is released upon heating to 450 °C.

Hydrogen carriers based on nanostructured carbon (such as carbon buckyballs and nanotubes) have been proposed. However, hydrogen content amounts up to ≈3.0-7.0 wt% at 77K which is far from the value set by US Department of Energy (6 wt% at nearly ambient conditions).

To realize carbon materials as effective hydrogen storage technologies, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been doped with MgH2. The metal hydride has proven to have a theoretical storage capacity (7.6 wt%) that fulfills the United States Department of Energy requirement of 6 wt%, but has limited practical applications due to its high release temperature. The proposed mechanism involves the creation of fast diffusion channels by CNTs within the MgH2 lattice. Fullerene is other carbonaceous nanomaterials that has been tested for hydrogen storage in this center. Fullerene molecules are composed of a C60 close-caged structure, that allows for hydrogenation of the double bonded carbons leading to a theoretical C60H60 isomer with a hydrogen content of 7.7 wt%. However, the release temperature in these systems is high (600 °C).

Metal-organic frameworks

Metal-organic frameworks represent another class of synthetic porous materials that store hydrogen and energy at the molecular level. MOFs are highly crystalline inorganic-organic hybrid structures that contain metal clusters or ions (secondary building units) as nodes and organic ligands as linkers. When guest molecules (solvent) occupying the pores are removed during solvent exchange and heating under vacuum, porous structure of MOFs can be achieved without destabilizing the frame and hydrogen molecules will be adsorbed onto the surface of the pores by physisorption. Compared to traditional zeolites and porous carbon materials, MOFs have very high number of pores and surface area which allow higher hydrogen uptake in a given volume. Thus, research interests on hydrogen storage in MOFs have been growing since 2003 when the first MOF-based hydrogen storage was introduced. Since there are infinite geometric and chemical variations of MOFs based on different combinations of SBUs and linkers, many researches explore what combination will provide the maximum hydrogen uptake by varying materials of metal ions and linkers.

Factors influencing hydrogen storage ability

Temperature, pressure and composition of MOFs can influence their hydrogen storage ability. The adsorption capacity of MOFs is lower at higher temperature and higher at lower temperatures. With the rising of temperature, physisorption decreases and chemisorption increases. For MOF-519 and MOF-520, the isosteric heat of adsorption decreased with pressure increase. For MOF-5, both gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen uptake increased with increase in pressure. The total capacity may not be consistent with the usable capacity under pressure swing conditions. For instance, MOF-5 and IRMOF-20, which have the highest total volumetric capacity, show the least usable volumetric capacity. Absorption capacity can be increased by modification of structure. For example, the hydrogen uptake of PCN-68 is higher than PCN-61. Porous aromatic frameworks (PAF-1), which is known as a high surface area material, can achieve a higher surface area by doping.

Modification of MOFs

There are many different ways to modify MOFs, such as MOF catalysts, MOF hybrids, MOF with metal centers and doping. MOF catalysts have high surface area, porosity and hydrogen storage capacity. However, the active metal centers are low. MOF hybrids have enhanced surface area, porosity, loading capacity and hydrogen storage capacity. Nevertheless, they are not stable and lack active centers. Doping in MOFs can increase hydrogen storage capacity, but there might be steric effect and inert metals have inadequate stability. There might be formation of interconnected pores and low corrosion resistance in MOFs with metal centers, while they might have good binding energy and enhanced stability. These advantages and disadvantages for different kinds of modified MOFs show that MOF hybrids are more promising because of the good controllability in selection of materials for high surface area, porosity and stability.

In 2006, chemists achieved hydrogen storage concentrations of up to 7.5 wt% in MOF-74 at a low temperature of 77 K. In 2009, researchers reached 10 wt% at 77 bar (1,117 psi) and 77 K with MOF NOTT-112. Most articles about hydrogen storage in MOFs report hydrogen uptake capacity at a temperature of 77K and a pressure of 1 bar because these conditions are commonly available and the binding energy between hydrogen and the MOF at this temperature is large compared to the thermal vibration energy. Varying several factors such as surface area, pore size, catenation, ligand structure, and sample purity can result in different amounts of hydrogen uptake in MOFs.

In 2020, researchers reported that NU-1501-Al, an ultraporous metal–organic framework (MOF) based on metal trinuclear clusters, yielded "impressive gravimetric and volumetric storage performances for hydrogen and methane", with a hydrogen delivery capacity of 14.0% w/w, 46.2 g/litre.

Cryo-compressed

Cryo-compressed storage of hydrogen is the only technology that meets 2015 DOE targets for volumetric and gravimetric efficiency (see "CcH2" on slide 6 in ).

Furthermore, another study has shown that cryo-compressed exhibits interesting cost advantages: ownership cost (price per mile) and storage system cost (price per vehicle) are actually the lowest when compared to any other technology (see third row in slide 13 of ). For example, a cryo-compressed hydrogen system would cost $0.12 per mile (including cost of fuel and every associated other cost), while conventional gasoline vehicles cost between $0.05 and $0.07 per mile.

Like liquid storage, cryo-compressed uses cold hydrogen (20.3 K and slightly above) in order to reach a high energy density. However, the main difference is that, when the hydrogen would warm-up due to heat transfer with the environment ("boil off"), the tank is allowed to go to pressures much higher (up to 350 bars versus a couple of bars for liquid storage). As a consequence, it takes more time before the hydrogen has to vent, and in most driving situations, enough hydrogen is used by the car to keep the pressure well below the venting limit.

Consequently, it has been demonstrated that a high driving range could be achieved with a cryo-compressed tank : more than 650 miles (1,050 km) were driven with a full tank mounted on an hydrogen-fueled engine of Toyota Prius. Research is still underway to study and demonstrate the full potential of the technology.

As of 2010, the BMW Group has started a thorough component and system level validation of cryo-compressed vehicle storage on its way to a commercial product.

Clathrate hydrates

H2 caged in a clathrate hydrate was first reported in 2002, but requires very high pressures to be stable. In 2004, researchers showed solid H2-containing hydrates could be formed at ambient temperature and 10s of bar by adding small amounts of promoting substances such as THF. These clathrates have a theoretical maximum hydrogen densities of around 5 wt% and 40 kg/m3.

Glass capillary arrays

A team of Russian, Israeli and German scientists have collaboratively developed an innovative technology based on glass capillary arrays for the safe infusion, storage and controlled release of hydrogen in mobile applications. The C.En technology has achieved the United States Department of Energy (DOE) 2010 targets for on-board hydrogen storage systems. DOE 2015 targets can be achieved using flexible glass capillaries and cryo-compressed method of hydrogen storage.

Glass microspheres

Hollow glass microspheres (HGM) can be utilized for controlled storage and release of hydrogen. HGMs with a diameter of 1 to 100 μm, a density of 1.0 to 2.0 gm/cc and a porous wall with openings of 10 to 1000 angstroms are considered for hydrogen storage. The advantages of HGMs for hydrogen storage are that they are nontoxic, light, cheap, recyclable, reversible, easily handled at atmospheric conditions, capable of being stored in a tank, and the hydrogen within is non-explosive. Each of these HGMs is capable of containing hydrogen up to 150 MPa without the heaviness and bulk of a large pressurized tank. All of these qualities are favorable in vehicular applications. Beyond these advantages, HGMs are seen as a possible hydrogen solution due to hydrogen diffusivity having a large temperature dependence. At room temperature, the diffusivity is very low, and the hydrogen is trapped in the HGM. The disadvantage of HGMs is that to fill and outgas hydrogen effectively the temperature must be at least 300 °C which significantly increases the operational cost of HGM in hydrogen storage. The high temperature can be partly attributed to glass being an insulator and having a low thermal conductivity; this hinders hydrogen diffusivity and therefore requiring a higher temperature to achieve the desired output.

To make this technology more economically viable for commercial use, research is being done to increase the efficiency of hydrogen diffusion through the HGMs. One study done by Dalai et al. sought to increase the thermal conductivity of the HGM through doping the glass with cobalt. In doing so they increased the thermal conductivity from 0.0072 to 0.198 W/m-K at 10 wt% Co. Increases in hydrogen adsorption though were only seen up to 2 wt% Co (0.103 W/m-K) as the metal oxide began to cover pores in the glass shell. This study concluded with a hydrogen storage capacity of 3.31 wt% with 2 wt% Co at 200 °C and 10 bar.

A study done by Rapp and Shelby sought to increase the hydrogen release rate through photo-induced outgassing in doped HGMs in comparison to conventional heating methods. The glass was doped with optically active metals to interact with the high-intensity infrared light. The study found that 0.5 wt% Fe3O4 doped 7070 borosilicate glass had hydrogen release increase proportionally to the infrared lamp intensity. In addition to the improvements to diffusivity by infrared alone, reactions between the hydrogen and iron-doped glass increased the Fe2+/Fe3+ ratio which increased infrared absorption therefore further increasing the hydrogen yield.

As of 2020, the progress made in studying HGMs has increased its efficiency but it still falls short of Department of Energy targets for this technology. The operation temperatures for both hydrogen adsorption and release are the largest barrier to commercialization.

Photo-Chemical storage

A method of storing hydrogen in light-activated hydrides has been developed. Hydrogen is stored in a layered nanophotonic structure deposited on a disk or a nano-graphite film; the hydrogen is released when laser light is applied. The photonic release process selectively releases protium but not deuterium. Consequently, after sustained used the material accumulates deuterium. After about 150 cycles, the material can be processed to extract deuterium for commercial use.

Stationary hydrogen storage

Unlike mobile applications, hydrogen density is not a huge problem for stationary applications. As for mobile applications, stationary applications can use established technology:

- Compressed hydrogen (CGH2) in a hydrogen tank

- Liquid hydrogen in a (LH2) cryogenic hydrogen tank

- Slush hydrogen in a cryogenic hydrogen tank

Underground hydrogen storage

Underground hydrogen storage is the practice of hydrogen storage in caverns, salt domes and depleted oil and gas fields. Large quantities of gaseous hydrogen have been stored in caverns by ICI for many years without any difficulties. The storage of large quantities of liquid hydrogen underground can function as grid energy storage. The round-trip efficiency is approximately 40% (vs. 75-80% for pumped-hydro (PHES)), and the cost is slightly higher than pumped hydro, if only a limited number of hours of storage is required. Another study referenced by a European staff working paper found that for large scale storage, the cheapest option is hydrogen at €140/MWh for 2,000 hours of storage using an electrolyser, salt cavern storage and combined-cycle power plant. The European project Hyunder indicated in 2013 that for the storage of wind and solar energy an additional 85 caverns are required as it cannot be covered by PHES and CAES systems. A German case study on storage of hydrogen in salt caverns found that if the German power surplus (7% of total variable renewable generation by 2025 and 20% by 2050) would be converted to hydrogen and stored underground, these quantities would require some 15 caverns of 500,000 cubic metres each by 2025 and some 60 caverns by 2050 – corresponding to approximately one third of the number of gas caverns currently operated in Germany. In the US, Sandia Labs are conducting research into the storage of hydrogen in depleted oil and gas fields, which could easily absorb large amounts of renewably produced hydrogen as there are some 2.7 million depleted wells in existence.

Power to gas

Power to gas is a technology which converts electrical power to a gas fuel. There are two methods: the first is to use the electricity for water splitting and inject the resulting hydrogen into the natural gas grid; the second, less efficient method is used to convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen to methane, (see natural gas) using electrolysis and the Sabatier reaction. A third option is to combine the hydrogen via electrolysis with a source of carbon (either carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide from biogas, from industrial processes or via direct air-captured carbon dioxide) via biomethanation, where biomethanogens (archaea) consume carbon dioxide and hydrogen and produce methane within an anaerobic environment. This process is highly efficient, as the archaea are self-replicating and only require low-grade (60 °C) heat to perform the reaction.

Another process has also been achieved by SoCalGas to convert the carbon dioxide in raw biogas to methane in a single electrochemical step, representing a simpler method of converting excess renewable electricity into storable natural gas.

The UK has completed surveys and is preparing to start injecting hydrogen into the gas grid as the grid previously carried 'town gas' which is a 50% hydrogen-methane gas formed from coal. Auditors KPMG found that converting the UK to hydrogen gas could be £150bn to £200bn cheaper than rewiring British homes to use electric heating powered by lower-carbon sources.

Excess power or off peak power generated by wind generators or solar arrays can then be used for load balancing in the energy grid. Using the existing natural gas system for hydrogen, Fuel cell maker Hydrogenics and natural gas distributor Enbridge have teamed up to develop such a power to gas system in Canada.

Pipeline storage of hydrogen where a natural gas network is used for the storage of hydrogen. Before switching to natural gas, the German gas networks were operated using towngas, which for the most part (60-65%) consisted of hydrogen. The storage capacity of the German natural gas network is more than 200,000 GW·h which is enough for several months of energy requirement. By comparison, the capacity of all German pumped storage power plants amounts to only about 40 GW·h. The transport of energy through a gas network is done with much less loss (<0.1%) than in a power network (8%). The use of the existing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen was studied by NaturalHy

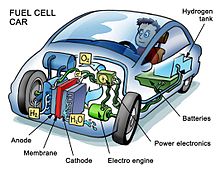

Automotive onboard hydrogen storage

Portability is one of the biggest challenges in the automotive industry, where high density storage systems are problematic due to safety concerns. High-pressure tanks weigh much more than the hydrogen they can hold. For example, in the 2014 Toyota Mirai, a full tank contains only 5.7% hydrogen, the rest of the weight being the tank.

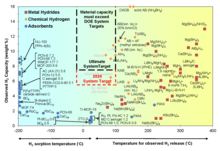

The US Department of Energy has set targets for onboard hydrogen storage for light vehicles. The list of requirements include parameters related to gravimetric and volumetric capacity, operability, durability and cost. These targets have been set as the goal for a multiyear research plan expected to offer an alternative to fossil fuels. The FreedomCAR Partnership, which was established under U.S. President George W. Bush, set targets for hydrogen vehicle fuel systems. The 2005 targets were not reached. The targets were revised in 2009 to reflect new data on system efficiencies obtained from fleets of test cars. In 2017 the 2020 and ultimate targets were lowered, with the ultimate targets set to 65 g H2 per kg total system weight, and 50 g H2 per litre of system.

It is important to note that these targets are for the hydrogen storage system, not the hydrogen storage material such as a hydride. System densities are often around half those of the working material, thus while a material may store 6 wt% H2, a working system using that material may only achieve 3 wt% when the weight of tanks, temperature and pressure control equipment, etc., is considered.

In 2010, only two storage technologies were identified as having the potential to meet DOE targets: MOF-177 exceeds 2010 target for volumetric capacity, while cryo-compressed H2 exceeds more restrictive 2015 targets for both gravimetric and volumetric capacity.

The target for fuel cell powered vehicles is to provide a driving range of over 300 miles. A long-term goal set by the US Fuel Cell Technology Office involves the use of nanomaterials to improve maximum range.

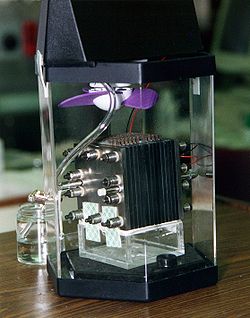

Fuel cells and storage

Due to its clean-burning characteristics, hydrogen is a clean fuel alternative for the automotive industry. Hydrogen-based fuel could significantly reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases such as CO2, SO2 and NOx. Three problems for the use of hydrogen fuel cells (HFC) are efficiency, size, and safe onboard storage of the gas. Other major disadvantages of this emerging technology involve cost, operability and durability issues, which still need to be improved from the existing systems. To address these challenges, the use of nanomaterials has been proposed as an alternative option to the traditional hydrogen storage systems. The use of nanomaterials could provide a higher density system and increase the driving range towards the target set by the DOE at 300 miles. Carbonaceous materials such as carbon nanotube and metal hydrides are the main focus of research. They are currently being considered for onboard storage systems due to their versatility, multi-functionality, mechanical properties and low cost with respect to other alternatives.

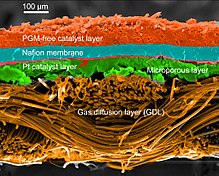

Other advantages of nanomaterials in fuel cells

The introduction of nanomaterials in onboard hydrogen storage systems may be a major turning point in the automotive industry. However, storage is not the only aspect of the fuel cell to which nanomaterials may contribute. Different studies have shown that the transport and catalytic properties of Nafion membranes used in HFCs can be enhanced with TiO2/SnO2 nanoparticles. The increased performance is caused by an improvement in hydrogen splitting kinetics due to catalytic activity of the nanoparticles. Furthermore, this system exhibits faster transport of protons across the cell which makes HFCs with nanoparticle composite membranes a promising alternative.

Another application of nanomaterials in water splitting has been introduced by a research group at Manchester Metropolitan University in the UK using screen-printed electrodes consisting of a graphene-like material. Similar systems have been developed using photoelectrochemical techniques.

Hydrogen storage now and in the future

The Hydrogen Storage Materials research field is vast, having tens of thousands of published papers. According to Papers in the 2000 to 2015 period collected from Web of Science and processed in VantagePoint® bibliometric software, a scientometric review of research in hydrogen storage materials was constituted. According to the literature, hydrogen energy went through

a hype-cycle type of development in the 2000's. Research in Hydrogen Storage Materials grew at increasing rates from 2000 to 2010. Afterwards, growth continued but at decreasing rates, and a plateau was reached in 2015. Looking at individual country output, there is a division between countries that after 2010 inflected to a constant or slightly declining production, such as the European Union countries, the US and Japan, and those whose production continued growing until 2015, such as China and South Korea. The countries with most publications were China, the EU and the USA, followed by Japan. China kept the leading position throughout the entire period, and had a higher share of hydrogen storage materials publications in its total research output.

Among materials classes, Metal-Organic Frameworks were the most researched materials, followed by Simple Hydrides. Three typical behaviors were identified: 1) New materials, researched mainly after 2004, such as MOFs and Borohydrides; 2) Classic materials, present through the entire period with growing number of papers, such as Simple Hydrides, and 3) Materials with stagnant or declining research through the end of the period, such as AB5 alloys and Carbon Nanotubes.

However, current physisorption technologies are still far from being commercialized. The experimental studies are executed for small samples less than 100 g. The described technologies require high pressure and/or low temperatures as a rule. Therefore, we consider these techniques at their current state of the art not as a separate novel technology but as a type of valuable add-on to current compression and liquefaction methods.

Physisorption processes are reversible since no activation energy is involved and the interaction energy is very low. In materials such as metal–organic frameworks, porous carbons, zeolites, clathrates, and organic polymers, hydrogen is physisorbed on the surface of the pores. In these classes of materials, the hydrogen storage capacity mainly depends on the surface area and pore volume. The main limitation of use of these sorbents as H2 storage materials is weak van der Waals interaction energy between hydrogen and the surface of the sorbents. Therefore, many of the physisorption based materials have high storage capacities at liquid nitrogen temperature and high pressures, but their capacities become very low at ambient temperature and pressure.

LOHC, liquid organic hydrogen storage systems is a promising technique for future hydrogen storage. LOHC are organic compounds that can absorb and release hydrogen through chemical reactions. These compounds are characterized by the fact that they can be loaded and un-loaded with considerable amounts of hydrogen in a cyclic process. In principle, every unsaturated compound (organic molecules with C-C double or triple bonds) can take up hydrogen during hydrogenation. This technique ensures that the release of compounds into the atmosphere are entirely avoided in hydrogen storage. Therefore, LOHCs is an attractive way to provide wind and solar energy for mobility applications in the form of liquid energy carrying molecules of similar energy storage densities and manageability as today's fossil fuels.