From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The history of capitalism is diverse. The concept of capitalism has many debated roots, but fully fledged capitalism is generally thought by scholars to have emerged in Northwestern Europe, especially in Great Britain and the Netherlands, in the 16th to 17th centuries. Over the following centuries, capital accumulated by a variety of methods, at a variety of scales, and became associated with much variation in the concentration of wealth and economic power. Capitalism gradually became the dominant economic system throughout the world. Much of the history of the past 500 years is concerned with the development of capitalism in its various forms.

Varieties of capitalism

It

is an ongoing debate within the fields of economics and sociology as to

what the past, current and future stages of capitalism are. While

ongoing disagreement about exact stages exists, many economists have

posited the following general states.

These states are not mutually exclusive and do not represent a fixed

order of historical change, but do represent a broadly chronological

trend.

- Accountable Capitalism

- Agrarian capitalism, sometimes known as market feudalism.

This was a transitional form between feudalism and capitalism, whereby

market relations replaced some but not all feudal relations in a

society.

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Authoritarian capitalism

- Common-good capitalism

- Compassionate capitalism

- Conscious capitalism

- Crony capitalism

- Democratic capitalism

- Financial capitalism, where financial

parts of the economy (like the finance, insurance, or real estate

sectors) predominate in an economy. Profit becomes more derived from

ownership of an asset, credit, rents and earning interest, rather than

productive processes.

- Gangster capitalism

- Industrial capitalism, characterized by its use of heavy machinery and a much more pronounced division of labor.

- Laissez-faire capitalism

- Late capitalism

- Monopoly capitalism,

marked by the rise of monopolies and trusts dominating industry and

other aspects of society. Often used to describe the economy of the late

19th and early 20th century.

- Neoliberal capitalism

- Racial capitalism

- Social capitalism

- Stakeholder capitalism

is a theoretical system in which corporations are oriented to serve the

interests of all their stakeholders. Among the key stakeholders are

shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, environment, and local

communities.

- State capitalism,

where the state intervened to prevent economic instability, including

partially or fully nationalizing certain industries. Some economists also include the economies of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc in this category.

- Surveillance capitalism

- Totalitarian capitalism

- Welfare capitalism,

the implementation of laws and government funded social programs, such

as minimum wage and universal healthcare, with the aim of creating a

social safety net. The heyday of welfare capitalism (in advanced

economies) is widely seen to be from 1945 to 1973 as major social safety nets were put in place in most advanced capitalist economies.

- Woke capitalism

- Colonialism,

where governments sought to colonize other areas to improve access to

markets and raw materials and assist state-owned capitalist firms.

- Corporatism, where government, business and labor collude to make major national decisions. Notable for being an economic model of fascism, it can overlap with, but is still significantly different from state capitalism.

- Mass production,

post-World War II, saw the rising power of major corporations and a

focus on mass production, mass consumption and (ideally) mass

employment. This stage

sees the rise of advertising as a way to promote mass consumption and

often sees significant economic planning taking place within firms.

- Mercantilism,

usually in historic context, is the use of a variety of economic

policies that aim to protect domestic trade from foreign competition,

commonly by raising tariffs on imported goods and giving subsidies to

domestic producers.

Historiography

The

processes by which capitalism emerged, evolved, and spread are the

subject of extensive research and debate among historians. Debates

sometimes focus on how to bring substantive historical data to bear on

key questions.

Key parameters of debate include: the extent to which capitalism is a

natural human behavior, versus the extent to which it arises from

specific historical circumstances; whether its origins lie in towns and

trade or in rural property relations; the role of class conflict; the

role of the state; the extent to which capitalism is a distinctively

European innovation; its relationship with European imperialism; whether

technological change is a driver or merely an epiphenomenon of

capitalism; and whether or not it is the most beneficial way to organize

human societies.

The historiography of capitalism can be divided into two broad schools. One is associated with economic liberalism, with the 18th-century economist Adam Smith as a foundational figure. The other is associated with Marxism, drawing particular inspiration from the 19th-century economist Karl Marx.

Liberals view capitalism as an expression of natural human

behaviors that have been in evidence for millennia and the most

beneficial way of promoting human well being. They see capitalism as originating in trade and commerce, and freeing people to exercise their entrepreneurial natures.

Marxists view capitalism as a historically unusual system of

relationships between classes, which could be replaced by other economic

systems that would serve human well being better.

They see capitalism as originating in more powerful people taking

control of the means of production, and compelling others to sell their

labour as a commodity. For these reasons, much of the work on the history of capitalism has been broadly Marxist.

Origins

The

origins of capitalism have been much debated (and depend partly on how

capitalism is defined). The traditional account, originating in

classical 18th-century liberal economic thought and still often

articulated, is the 'commercialization model'. This sees capitalism

originating in trade. Since evidence for trade is found even in

paleolithic culture, it can be seen as natural to human societies. In

this reading, capitalism emerged from earlier trade once merchants had

acquired sufficient wealth (referred to as 'primitive capital')

to begin investing in increasingly productive technology. This account

tends to see capitalism as a continuation of trade, arising when

people's natural entrepreneurialism was freed from the constraints of feudalism, partly by urbanization. Thus it traces capitalism to early forms of merchant capitalism practiced in Western Europe during the Middle Ages.

Other views

A competitor to the 'commercialization model' is the 'agrarian model',

which explains the rise of capitalism by unique circumstances in

English agrarianism. The evidence it cites is that traditional

mercantilism focused on moving goods from markets where they were cheap

to markets where they were expensive rather than investing in

production, and that many cultures (including the early modern Dutch Republic) saw urbanisation and the amassing of wealth by merchants without the emergence of capitalist production.

The agrarian argument developed particularly through Karl Polanyi's The Great Transformation (1944), Maurice Dobb's Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946), and Robert Brenner's research in the 1970s, the discussion of which is known as the Brenner Debate. In the wake of the Norman Conquest,

the English state was unusually centralised. This gave aristocrats

relatively limited powers to extract wealth directly from their feudal

underlings through political means (not least the threat of violence).

England's centralisation also meant that an unusual number of English

farmers were not peasants (with their own land and thus direct access to

subsistence) but tenants

(renting their land). These circumstances produced a market in leases.

Landlords, lacking other ways to extract wealth, were motivated to rent

to tenants who could pay the most, while tenants, lacking security of

tenure, were motivated to farm as productively as possible to win leases

in a competitive market. This led to a cascade of effects whereby

successful tenant farmers became agrarian capitalists; unsuccessful ones

became wage-labourers, required to sell their labour in order to live;

and landlords promoted the privatisation and renting out of common land,

not least through the enclosures.

In this reading, 'it was not merchants or manufacturers who drove the

process that propelled the early development of capitalism. The

transformation of social property relations was firmly rooted in the

countryside, and the transformation of England's trade and industry was

result more than cause of England's transition to capitalism'.

21st-century developments

The

21st century has seen renewed interest in the history of capitalism,

and "History of Capitalism" has become a field in its own right, with

courses in history departments. In the 2000s, Harvard University founded

the Program on the Study of U.S. Capitalism; Cornell University

established the History of Capitalism Initiative; and Columbia University Press launched a monograph series titled Studies in the History of U.S. Capitalism.

This field includes topics such as insurance, banking and regulation,

the political dimension, and the impact on the middle classes, the poor

and women and minorities.

These initiatives incorporate formerly neglected questions of race,

gender, and sexuality into the history of capitalism. They have grown in

the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the associated Great Recession.

Some other academic institutions, such as the Clemson Institute

for the Study of Capitalism, reject the notion that race, gender, or

sexuality have any significant relationship to capitalism at all and

instead seek to show that laissez-faire capitalism, in particular,

provides the best and most numerous economic opportunities for all

people.

Agrarian capitalism

Crisis of the 14th century

Map of a

medieval manor. Notice the large commons area and the division of land into small strips. The mustard-colored areas are part of the

demesne, the

hatched areas part of the

glebe.

William R. Shepherd,

Historical Atlas, 01923

According to some historians, the modern capitalist system originated in the "crisis of the Late Middle Ages", a conflict between the land-owning aristocracy and the agricultural producers, or serfs. Manorial

arrangements inhibited the development of capitalism in a number of

ways. Serfs had obligations to produce for lords and therefore had no

interest in technological innovation; they also had no interest in

cooperating with one another because they produced to sustain their own

families. The lords who owned the land

relied on force to guarantee that they received sufficient food.

Because lords were not producing to sell on the market, there was no

competitive pressure for them to innovate. Finally, because lords

expanded their power and wealth through military means, they spent their

wealth on military equipment or on conspicuous consumption that helped foster alliances with other lords; they had no incentive to invest in developing new productive technologies.

The demographic

crisis of the 14th century upset this arrangement. This crisis had

several causes: agricultural productivity reached its technological

limitations and stopped growing, bad weather led to the Great Famine of 1315–1317, and the Black Death of 1348–1350 led to a population crash. These factors led to a decline in agricultural production. In response, feudal lords

sought to expand agricultural production by extending their domains

through warfare; therefore they demanded more tribute from their serfs

to pay for military expenses. In England, many serfs rebelled. Some

moved to towns, some bought land, and some entered into favorable

contracts to rent lands from lords who needed to repopulate their

estates.

The collapse of the manorial system in England enlarged the class of tenant farmers

with more freedom to market their goods and thus more incentive to

invest in new technologies. Lords who did not want to rely on renters

could buy out or evict tenant farmers, but then had to hire free labor

to work their estates, giving them an incentive to invest in two kinds

of commodity owners. One kind was those who had money, the means of

production, and subsistence, who were eager to valorize the sum of value they had appropriated by buying the labor power of others.

The other kind was free workers, who sold their own labor. The workers

neither formed part of the means of production nor owned the means of

production that transformed land and even money into what we now call

"capital". Marx labeled this period the "pre-history of capitalism".

In effect, feudalism began to lay some of the foundations necessary for the development of mercantilism, a precursor of capitalism. Feudalism was mostly confined to Europe

and lasted from the medieval period through the 16th century. Feudal

manors were almost entirely self-sufficient, and therefore limited the

role of the market. This stifled any incipient tendency towards

capitalism. However, the relatively sudden emergence of new technologies

and discoveries, particularly in agriculture and exploration, facilitated the growth of capitalism. The most important development at the end of feudalism was the emergence of what Robert Degan calls "the dichotomy between wage earners and capitalist merchants".

The competitive nature meant there are always winners and losers, and

this became clear as feudalism evolved into mercantilism, an economic

system characterized by the private or corporate ownership of capital

goods, investments determined by private decisions, and by prices,

production, and the distribution of goods determined mainly by

competition in a free market.

Enclosure

Decaying hedges mark the lines of the straight field boundaries created by a Parliamentary Act of Enclosure.

England in the 16th century was already a centralized state, in which much of the feudal order of Medieval Europe

had been swept away. This centralization was strengthened by a good

system of roads and a disproportionately large capital city, London.

The capital acted as a central market for the entire country, creating a

large internal market for goods, in contrast to the fragmented feudal

holdings that prevailed in most parts of the Continent.

The economic foundations of the agricultural system were also beginning

to diverge substantially; the manorial system had broken down by this

time, and land began to be concentrated in the hands of fewer landlords

with increasingly large estates. The system put pressure on both the

landlords and the tenants to increase agricultural productivity to

create profit. The weakened coercive power of the aristocracy to extract peasant surpluses

encouraged them to try out better methods. The tenants also had an

incentive to improve their methods to succeed in an increasingly

competitive labour market.

Land rents had moved away from the previous stagnant system of custom

and feudal obligation, and were becoming directly subject to economic

market forces.

An important aspect of this process of change was the enclosure of the common land previously held in the open field system where peasants had traditional rights, such as mowing meadows for hay and grazing livestock.

Once enclosed, these uses of the land became restricted to the owner,

and it ceased to be land for commons. The process of enclosure began to

be a widespread feature of the English agricultural landscape during the

16th century. By the 19th century, unenclosed commons had become

largely restricted to rough pasture in mountainous areas and to

relatively small parts of the lowlands.

Marxist and neo-Marxist historians

argue that rich landowners used their control of state processes to

appropriate public land for their private benefit. This created a

landless working class that provided the labour required in the new industries developing in the north of England.

For example: "In agriculture the years between 1760 and 1820 are the

years of wholesale enclosure in which, in village after village, common

rights are lost". "Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery". Anthropologist Jason Hickel notes that this process of enclosure led to myriad peasant revolts, among them Kett's Rebellion and the Midland Revolt, which culminated in violent repression and executions.

Other scholars argue that the better-off members of the European peasantry encouraged and participated actively in enclosure, seeking to end the perpetual poverty of subsistence farming.

"We should be careful not to ascribe to [enclosure] developments that

were the consequence of a much broader and more complex process of

historical change." "[T]he impact of eighteenth and nineteenth century enclosure has been grossly exaggerated...."

Merchant capitalism and mercantilism

Precedents

A painting of a French seaport from 1638, at the height of mercantilism.

While trade has existed since early in human history, it was not capitalism. The earliest recorded activity of long-distance profit-seeking merchants can be traced to the Old Assyrian merchants active in Mesopotamia the 2nd millennium BCE.

The Roman Empire developed more advanced forms of commerce, and

similarly widespread networks existed in Islamic nations. However,

capitalism took shape in Europe in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

An early emergence of commerce occurred on monastic estates in Italy and France and in the independent city republics of Italy during the late Middle Ages.

Innovations in banking, insurance, accountancy, and various production

and commercial practices linked closely to a 'spirit' of frugality,

reinvestment, and city life, promoted attitudes that sociologists have

tended to associate only with northern Europe, Protestantism, and a much later age. The city republics maintained their political independence from Empire and Church, traded with North Africa, the Middle East and Asia,

and introduced Eastern practices. They were also considerably different

from the absolutist monarchies of Spain and France, and were strongly

attached to civic liberty.

Emergence

Modern capitalism only fully emerged in the early modern period between the 16th and 18th centuries, with the establishment of mercantilism or merchant capitalism. Early evidence for mercantilistic practices appears in early modern Venice, Genoa, and Pisa over the Mediterranean trade in bullion. The region of mercantilism's real birth, however, was the Atlantic Ocean.

England began a large-scale and integrative approach to mercantilism during the Elizabethan Era. An early statement on national balance of trade appeared in Discourse of the Common Weal of this Realm of England,

1549: "We must always take heed that we buy no more from strangers than

we sell them, for so should we impoverish ourselves and enrich them." The period featured various but often disjointed efforts by the court of Queen Elizabeth

to develop a naval and merchant fleet capable of challenging the

Spanish stranglehold on trade and of expanding the growth of bullion at

home. Elizabeth promoted the Trade and Navigation Acts in Parliament and

issued orders to her navy for the protection and promotion of English

shipping.

These efforts organized national resources sufficiently in the defense of England against the far larger and more powerful Spanish Empire, and in turn paved the foundation for establishing a global empire in the 19th century. The authors noted most for establishing the English mercantilist system include Gerard de Malynes and Thomas Mun, who first articulated the Elizabethan System. The latter's England's Treasure by Forraign Trade, or the Balance of our Forraign Trade is The Rule of Our Treasure gave a systematic and coherent explanation of the concept of balance of trade. It was written in the 1620s and published in 1664. Mercantile doctrines were further developed by Josiah Child. Numerous French authors helped to cement French policy around mercantilism in the 17th century. French mercantilism was best articulated by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (in office, 1665–1683), although his policies were greatly liberalised under Napoleon.

Doctrines

Under mercantilism, European merchants, backed by state controls, subsidies, and monopolies, made most of their profits from buying and selling goods. In the words of Francis Bacon,

the purpose of mercantilism was "the opening and well-balancing of

trade; the cherishing of manufacturers; the banishing of idleness; the

repressing of waste and excess by sumptuary laws; the improvement and

husbanding of the soil; the regulation of prices..."

Similar practices of economic regimentation had begun earlier in

medieval towns. However, under mercantilism, given the contemporaneous

rise of absolutism, the state superseded the local guilds as the regulator of the economy.

The

Anglo-Dutch Wars were fought between the English and the Dutch for control over the seas and trade routes.

Among the major tenets of mercantilist theory was bullionism, a doctrine stressing the importance of accumulating precious metals.

Mercantilists argued that a state should export more goods than it

imported so that foreigners would have to pay the difference in precious

metals. Mercantilists asserted that only raw materials that could not

be extracted at home should be imported. They promoted the idea that

government subsidies, such as granting monopolies and protective tariffs, were necessary to encourage home production of manufactured goods.

Proponents of mercantilism emphasized state power and overseas

conquest as the principal aim of economic policy. If a state could not

supply its own raw materials, according to the mercantilists, it should

acquire colonies from which they could be extracted. Colonies

constituted not only sources of raw materials but also markets for

finished products. Because it was not in the interests of the state to

allow competition, to help the mercantilists, colonies should be

prevented from engaging in manufacturing and trading with foreign

powers.

Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although

commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production

methods. Noting the various pre-capitalist features of mercantilism, Karl Polanyi

argued that "mercantilism, with all its tendency toward

commercialization, never attacked the safeguards which protected [the]

two basic elements of production – labor and land – from becoming the

elements of commerce." Thus mercantilist regulation was more akin to

feudalism than capitalism. According to Polanyi, "not until 1834 was a

competitive labor market established in England, hence industrial

capitalism as a social system cannot be said to have existed before that

date."

Chartered trading companies

British East India Company 1801

The Muscovy Company was the first major chartered joint stock English trading company. It was established in 1555 with a monopoly on trade between England and Muscovy. It was an offshoot of the earlier Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, founded in 1551 by Richard Chancellor, Sebastian Cabot and Sir Hugh Willoughby to locate the Northeast Passage to China to allow trade. This was the precursor to a type of business that would soon flourish in England, the Dutch Republic and elsewhere.

The British East India Company (1600) and the Dutch East India Company (1602) launched an era of large state chartered trading companies. These companies were characterized by their monopoly on trade, granted by letters patent provided by the state. Recognized as chartered joint-stock companies by the state, these companies enjoyed lawmaking, military, and treaty-making privileges. Characterized by its colonial and expansionary powers by states, powerful nation-states sought to accumulate precious metals, and military conflicts arose.

During this era, merchants, who had previously traded on their own,

invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking

a return on investment.

Industrial capitalism

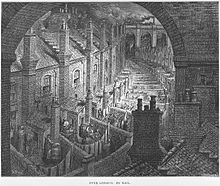

Gustave Doré's 19th-century engraving depicted the dirty, overcrowded slums where the industrial workers of London lived.

Mercantilism declined in Great Britain in the mid-18th century, when a new group of economic theorists, led by Adam Smith,

challenged fundamental mercantilist doctrines, such as that the world's

wealth remained constant and that a state could only increase its

wealth at the expense of another state. However, mercantilism continued

in less developed economies, such as Prussia and Russia, with their much younger manufacturing bases.

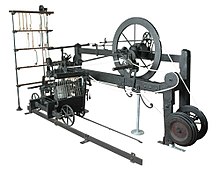

The mid-18th century gave rise to industrial capitalism, made

possible by (1) the accumulation of vast amounts of capital under the

merchant phase of capitalism and its investment in machinery, and (2)

the fact that the enclosures meant that Britain had a large population

of people with no access to subsistence agriculture, who needed to buy

basic commodities via the market, ensuring a mass consumer market.

Industrial capitalism, which Marx dated from the last third of the 18th

century, marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing,

characterized by a complex division of labor

between and within work processes and the routinization of work tasks.

Industrial capitalism finally established the global domination of the

capitalist mode of production.

During the resulting Industrial Revolution,

the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the

capitalist system, which led to the decline of the traditional

handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen.

Also during this period, capitalism transformed relations between the

British landowning gentry and peasants, giving rise to the production of

cash crops for the market rather than for subsistence on a feudal manor. The surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture.

Industrial Revolution

The productivity gains of capitalist production began a sustained and

unprecedented increase at the turn of the 19th century, in a process

commonly referred to as the Industrial Revolution.

Starting in about 1760 in England, there was a steady transition to new

manufacturing processes in a variety of industries, including going

from hand production methods to machine production, new chemical

manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power and the development of machine tools. It also included the change from wood and other bio-fuels to coal.

In textile manufacturing,

mechanized cotton spinning powered by steam or water increased the

output of a worker by a factor of about 1000, due to the application of James Hargreaves' spinning jenny, Richard Arkwright's water frame, Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule and other inventions. The power loom increased the output of a worker by a factor of over 40.

The cotton gin increased the productivity of removing seed from cotton

by a factor of 50. Large gains in productivity also occurred in spinning

and weaving wool and linen, although they were not as great as in

cotton.

Finance

The growth of Britain's industry stimulated a concomitant growth in its system of finance and credit. In the 18th century, services offered by banks increased. Clearing facilities, security investments, cheques and overdraft

protections were introduced. Cheques had been invented in the 17th

century in England, and banks settled payments by direct courier to the

issuing bank. Around 1770, they began meeting in a central location,

and by the 19th century a dedicated space was established, known as a bankers' clearing house.

The London clearing house used a method where each bank paid cash to

and then was paid cash by an inspector at the end of each day. The first

overdraft facility was set up in 1728 by The Royal Bank of Scotland.

The end of the Napoleonic War and the subsequent rebound in trade led to an expansion in the bullion reserves held by the Bank of England, from a low of under 4 million pounds in 1821 to 14 million pounds by late 1824.

Older innovations became routine parts of financial life during the 19th century. The Bank of England

first issued bank notes during the 17th century, but the notes were

hand written and few in number. After 1725, they were partially printed,

but cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to a

named person. In 1844, parliament passed the Bank Charter Act tying these notes to gold reserves, effectively creating the institution of central banking and monetary policy. The notes became fully printed and widely available from 1855.

Growing international trade increased the number of banks,

especially in London. These new "merchant banks" facilitated trade

growth, profiting from England's emerging dominance in seaborne

shipping. Two immigrant families, Rothschild and Baring,

established merchant banking firms in London in the late 18th century

and came to dominate world banking in the next century. The tremendous

wealth amassed by these banking firms soon attracted much attention. The

poet George Gordon Byron wrote in 1823: "Who makes politics run glibber all?/ The shade of Bonaparte's noble daring?/ Jew Rothschild and his fellow-Christian, Baring."

The operation of banks also shifted. At the beginning of the

century, banking was still an elite preoccupation of a handful of very

wealthy families. Within a few decades, however, a new sort of banking

had emerged, owned by anonymous stockholders, run by professional managers,

and the recipient of the deposits of a growing body of small

middle-class savers. Although this breed of banks was newly prominent,

it was not new – the Quaker family Barclays had been banking in this way since 1690.

Free trade and globalization

At the height of the First French Empire, Napoleon sought to introduce a "continental system"

that would render Europe economically autonomous, thereby emasculating

British trade and commerce. It involved such stratagems as the use of beet sugar

in preference to the cane sugar that had to be imported from the

tropics. Although this caused businessmen in England to agitate for

peace, Britain persevered, in part because it was well into the industrial revolution. The war had the opposite effect – it stimulated the growth of certain industries, such as pig-iron production which increased from 68,000 tons in 1788 to 244,000 by 1806.

In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens, in the famous theory of comparative advantage, argued that free trade would benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics:

- When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it

produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both

countries benefit.

By the mid 19th century, Britain was firmly wedded to the notion of free trade, and the first era of globalization began. In the 1840s, the Corn Laws and the Navigation Acts were repealed, ushering in a new age of free trade. In line with the teachings of the classical political economists, led by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Britain embraced liberalism, encouraging competition and the development of a market economy.

Industrialization allowed cheap production of household items using economies of scale, while rapid population growth created sustained demand for commodities. Nineteenth-century imperialism decisively shaped globalization in this period. After the First and Second Opium Wars

and the completion of the British conquest of India, vast populations

of these regions became ready consumers of European exports. During this

period, areas of sub-Saharan

Africa and the Pacific islands were incorporated into the world system.

Meanwhile, the European conquest of new parts of the globe, notably

sub-Saharan Africa, yielded valuable natural resources such as rubber, diamonds and coal and helped fuel trade and investment between the European imperial powers, their colonies, and the United States.

The

gold standard formed the financial basis of the international economy from 1870 to 1914.

The inhabitant of London could

order by telephone, sipping his morning tea, the various products of the

whole earth, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his

doorstep. Militarism and imperialism of racial and cultural rivalries

were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper. What an

extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man was that age which

came to an end in August 1914.

The global financial system was mainly tied to the gold standard during this period. The United Kingdom first formally adopted this standard in 1821. Soon to follow was Canada in 1853, Newfoundland in 1865, and the United States and Germany (de jure) in 1873. New technologies, such as the telegraph, the transatlantic cable, the Radiotelephone, the steamship, and the railway allowed goods and information to move around the world at an unprecedented degree.

The eruption of civil war in the United States in 1861 and the blockade of its ports to international commerce meant that the main supply of cotton for the Lancashire

looms was cut off. The textile industries shifted to reliance upon

cotton from Africa and Asia during the course of the U.S. civil war, and

this created pressure for an Anglo-French controlled canal through the Suez peninsula. The Suez canal opened in 1869, the same year in which the Central Pacific Railroad

that spanned the North American continent was completed. Capitalism and

the engine of profit were making the globe a smaller place.

Effects on workers

Industrialization

brought about divisions of labor, improved sanitation, dramatically

increased free time, rising wages, and falling demand for dangerous farm

work, all of which contributed to tremendous improvements in health and

longevity for early industrial workers, despite the hazardous

conditions in some primitive factories. Average life expectancy in Europe and America was 34–35 years in 1800; this number had risen to 68 years by 1950.

20th century

Several major challenges to capitalism appeared in the early part of the 20th century. The Russian revolution in 1917 established the first Communist state in the world; a decade later, the Great Depression triggered increasing criticism of the existing capitalist system. One response to this crisis was a turn to fascism, an ideology that advocated state capitalism. Another response was to reject capitalism altogether in favour of communist or democratic socialist ideologies.

Keynesianism and free markets

The economic recovery of the world's leading capitalist economies in

the period following the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War—a period of unusually rapid growth by historical standards—eased discussion of capitalism's eventual decline or demise.

The state began to play an increasingly prominent role to moderate and

regulate the capitalistic system throughout much of the world.

Keynesian economics became a widely accepted method of government regulation and countries such as the United Kingdom experimented with mixed economies in which the state owned and operated certain major industries.

The state also expanded in the US; in 1929, total government expenditures amounted to less than one-tenth of GNP; from the 1970s they amounted to around one-third.

Similar increases were seen in all industrialised capitalist economies,

some of which, such as France, have reached even higher ratios of

government expenditures to GNP than the United States.

A broad array of new analytical tools in the social sciences were developed to explain the social and economic trends of the period, including the concepts of post-industrial society and the welfare state.

The long post-war boom ended in the 1970s, amid the economic crises experienced following the 1973 oil crisis. The "stagflation" of the 1970s led many economic commentators and politicians to embrace market-oriented policy prescriptions inspired by the laissez-faire capitalism and classical liberalism of the nineteenth century, particularly under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. The theoretical alternative to Keynesianism

was more compatible with laissez-faire and emphasised rapid expansion

of the economy. Market-oriented solutions gained increasing support in

the Western world, especially under the leadership of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s. Public and political interest began shifting away from the so-called collectivist concerns of Keynes's managed capitalism to a focus on individual choice, called "remarketized capitalism".

Globalization

Although overseas trade has been associated with the development of

capitalism for over five hundred years, some thinkers argue that a

number of trends associated with globalisation

have acted to increase the mobility of people and capital since the

last quarter of the twentieth century, combining to circumscribe the

room to manoeuvre of states in choosing non-capitalist models of

development. Today, these trends have bolstered the argument that

capitalism should now be viewed as a truly world system

(Burnham). However, other thinkers argue that globalisation, even in

its quantitative degree, is no greater now than during earlier periods

of capitalist trade.

After the abandonment of the Bretton Woods system

in 1971, and the strict state control of foreign exchange rates, the

total value of transactions in foreign exchange was estimated to be at

least twenty times greater than that of all foreign movements of goods

and services (EB). The internationalisation of finance, which some see

as beyond the reach of state control, combined with the growing ease

with which large corporations have been able to relocate their

operations to low-wage states, has posed the question of the 'eclipse'

of state sovereignty, arising from the growing 'globalization' of

capital.

While economists generally agree about the size of global income inequality, there is a general disagreement about the recent direction of change of it. In cases such as China, where income inequality is clearly growing it is also evident that overall economic growth has rapidly increased with capitalist reforms. The book The Improving State of the World, published by the libertarian think tank Cato Institute, argues that economic growth since the Industrial Revolution has been very strong and that factors such as adequate nutrition, life expectancy, infant mortality, literacy, prevalence of child labor, education, and available free time have improved greatly. Some scholars, including Stephen Hawking and researchers for the International Monetary Fund, contend that globalization and neoliberal economic policies are not ameliorating inequality and poverty but exacerbating it, and are creating new forms of contemporary slavery. Such policies are also expanding populations of the displaced, the unemployed and the imprisoned along with accelerating the destruction of the environment and species extinction.

In 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in spite of

global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that

it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization. Surging economic inequality following the economic crisis and the anger associated with it have resulted in a resurgence of socialist and nationalist ideas throughout the Western world, which has some economic elites from places including Silicon Valley, Davos and Harvard Business School concerned about the future of capitalism.

Today

By the

beginning of the twenty-first century, mixed economies with capitalist

elements had become the pervasive economic systems worldwide. The

collapse of the Soviet bloc

in 1991 significantly reduced the influence of Communism as an

alternative economic system. Leftist movements continue to be

influential in some parts of the world, most notably Latin-American Bolivarianism, with some having ties to more traditional anti-capitalist movements, such as Bolivarian Venezuela's ties to Cuba.

In many emerging markets, the influence of banking and financial

capital have come to increasingly shape national developmental

strategies, leading some to argue we are in a new phase of financial

capitalism.

State intervention in global capital markets following the financial crisis of 2007–2010

was perceived by some as signalling a crisis for free-market

capitalism. Serious turmoil in the banking system and financial markets

due in part to the subprime mortgage crisis reached a critical stage during September 2008, characterised by severely contracted liquidity in the global credit markets posed an existential threat to investment banks and other institutions.

Future

According to some, the transition to the information society

involves abandoning some parts of capitalism, as the "capital" required

to produce and process information becomes available to the masses and

difficult to control, and is closely related to the controversial issues

of intellectual property. Some even speculate that the development of mature nanotechnology, particularly of universal assemblers, may make capitalism obsolete, with capital

ceasing to be an important factor in the economic life of humanity.

Various thinkers have also explored what kind of economic system might replace capitalism, such as Bob Avakian and Paul Mason.

Role of women

Women's historians have debated the impact of capitalism on the status of women. Alice Clark

argues that, when capitalism arrived in 17th-century England, it

negatively impacted the status of women, who lost much of their economic

importance. Clark argues that, in 16th-century England, women were

engaged in many aspects of industry and agriculture. The home was a

central unit of production, and women played a vital role in running

farms and in some trades and landed estates. Their useful economic roles

gave them a sort of equality with their husbands. However, Clark

argues, as capitalism expanded in the 17th century, there was more and

more division of labor, with the husband taking paid labor jobs outside

the home, and the wife reduced to unpaid household work. Middle-class

women were confined to an idle domestic existence, supervising servants;

lower-class women were forced to take poorly paid jobs. Capitalism,

therefore, had a negative effect on women. By contrast, Ivy Pinchbeck argues that capitalism created the conditions for women's emancipation.

Tilly and Scott have emphasized the continuity and the status of women,

finding three stages in European history. In the preindustrial era,

production was mostly for home use, and women produced many household

needs. The second stage was the "family wage economy" of early

industrialization. During this stage, the entire family depended on the

collective wages of its members, including husband, wife, and older

children. The third, or modern, stage is the "family consumer economy",

in which the family is the site of consumption, and women are employed

in large numbers in retail and clerical jobs to support rising standards

of consumption.