From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Christian doctrine

Throughout

the medieval era, mainstream Christian doctrine had denied the

existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan

superstition. Some have argued that the work of the Dominican Thomas Aquinas

in the 13th century helped lay the groundwork for a shift in Christian

doctrine, by which certain Christian theologians eventually began to

accept the possibility of collaboration with devil(s), resulting in a

person obtaining certain real supernatural powers.

Dominican Inquisitors and the Growth of Witch-phobia

A branch of the inquisition in southern France

In 1233, a papal bull by Gregory IX established a new branch of the inquisition in Toulouse, France, to be led by the Dominicans. It was intended to prosecute Christian groups considered heretical, such as the Cathars and the Waldensians.

The Dominicans eventually evolved into the most zealous prosecutors of

persons accused of witchcraft in the years leading up to the

Reformation.

Records were usually kept by the French inquisitors but the

majority of these did not survive, and one historian working in 1880,

Charles Molinier, refers to the surviving records as only scanty debris.

Molinier notes that the inquisitors themselves describe their attempts

to carefully safeguard their records, especially when moving from town

to town. The inquisitors were widely hated and would be ambushed on the

road, but their records were more often the target than the inquisitors

themselves [plus désireux encore de ravir les papiers que porte le juge que de le faire périr lui-même] (better to take the papers the judge carries than to make the judge himself perish).

The records seem to have often been targeted by the accused or their

friends and family, wishing to thereby sabotage the proceedings or

failing that, to spare their reputations and the reputations of their

descendants.

This would be all the more true of those accused of witchcraft.

Difficulty in understanding the larger witchcraft trials to come in

later centuries is deciding how much can be extrapolated from what

remains.

14th century

In

1329, with the papacy in nearby Avignon, the inquisitor of Carcassonne

sentenced a monk to the dungeon for life and the sentence refers to... multas et diversas daemonum conjurationes et invocationes... and frequently uses the same Latin synonym for witchcraft, sortilegia—found on the title page of Nicolas Rémy's work from 1595, where it is claimed that 900 persons were executed for sortilegii crimen.

15th century trials and the growth of the new heterodox view

The skeptical Canon Episcopi

retained many supporters, and still seems to have been supported by the

theological faculty at the University of Paris in their decree from

1398, and was never officially repudiated by a majority of bishops

within the papal lands, nor even by the Council of Trent, which immediately preceded the peak of the trials. But in 1428, the Valais witch trials,

lasting six to eight years, started in the French-speaking lower Valais

and eventually spread to German-speaking regions. This time period also

coincided with the Council of Basel

(1431–1437) and some scholars have suggested a new anti-witchcraft

doctrinal view may have spread among certain theologians and inquisitors

in attendance at this council, as the Valais trials were discussed.

Not long after, a cluster of powerful opponents of the Canon Episcopi

emerged: a Dominican inquisitor in Carcassonne named Jean Vinet, the

Bishop of Avila Alfonso Tostado, and another Dominican Inquisitor named Nicholas Jacquier.

It is unclear whether the three men were aware of each other's work.

The coevolution of their shared view centres around "a common challenge:

disbelief in the reality of demonic activity in the world."

Nicholas Jacquier's lengthy and complex argument against the

Canon Episcopi was written in Latin. It began as a tract in 1452 and was

expanded into a fuller monograph in 1458. Many copies seem to have been

made by hand (nine manuscript copies still exist), but it was not

printed until 1561. Jacquier describes a number of trials he personally witnessed, including one of a man named Guillaume Edelin,

against whom the main charge seems to have been that he had preached a

sermon in support of the Canon Episcopi claiming that witchcraft was

merely an illusion. Edeline eventually recanted this view, most likely

under torture.

Title page of the seventh

Cologne edition of the

Malleus Maleficarum, 1520 (from the

University of Sydney Library). The Latin title is "

MALLEUS MALEFICARUM, Maleficas, & earum hæresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens." (Generally translated into English as

The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword).

1486: Malleus Maleficarum

The most important and influential book promoting the new heterodox view was the Malleus Maleficarum by Heinrich Kramer.

Kramer begins his work in opposition to the Canon Episcopi, but oddly,

he does not cite Jacquier, and may not have been aware of his work.

Like most witch-phobic writers, Kramer had met strong resistance by

those who opposed his heterodox view; this inspired him to write his

work as both propaganda and a manual for like-minded zealots. The Gutenberg printing press

had only recently been invented along the Rhine River, and Kramer fully

utilized it to shepherd his work into print and spread the ideas that

had developed by inquisitors and theologians in France into the

Rhineland.

The theological views espoused by Kramer were influential but remained

contested, and an early edition of the book even appeared on a list of

those banned by the Church in 1490. Nonetheless Malleus Maleficarum

was printed 13 times between 1486 and 1520, and — following a 50-year

pause that coincided with the height of the Protestant reformations — it

was printed again another 16 times (1574–1669) in the decades following

the important Council of Trent

which had remained silent with regard to Kramer's theological views. It

inspired many similar works, such as an influential work by Jean Bodin, and was cited as late as 1692 by Increase Mather, then president of Harvard College.

It is unknown if a degree of alarm at the extreme superstition and anti-witchcraft views expressed by Kramer in the Malleus Maleficarum may have been one of the numerous factors that helped prepare the ground for the Protestant Reformation.

Peak of the trials: 1560–1630

The period of the European witch trials, with the largest number of fatalities, seems to have occurred between 1560 and 1630.

Authors have debated whether witch trials were more intense in

Catholic or Protestant regions. However, the intensity of persecutions

had not so much to do with Catholicism or Protestantism as such, as

there are examples of both intense and less intense witchcraft

persecutions from both Catholic and Protestant regions of Europe. In

Catholic Spain and Portugal for example, the numbers of witch trials

were few because the Spanish and the Portuguese Inquisition preferred to

focus on the crime of public heresy

rather than witchcraft, whereas Protestant Scotland had a much larger

number of witchcraft trials. In contrast, the witch trials in Protestant

Netherlands stopped earlier and were among the least numerous in

Europe, while the large-scale mass witch trials which took place in the

autonomous territories of the Catholic prince-bishops in Southern Germany were infamous in all of the Western World, and the contemporary writer Herman Löher described how they affected the population within them:

The Roman Catholic subjects, farmers, winegrowers, and

artisans in the episcopal lands are the most terrified people on earth,

since the false witch trials affect the German episcopal lands

incomparably more than France, Spain, Italy or Protestants.

The mass witch trials which took place in Southern Catholic Germany

in waves between the 1560s and the 1620s could continue for years and

result in hundreds of executions of all sexes, ages and classes. These

included the Trier witch trials (1581–1593), the Fulda witch trials (1603–1606), the Eichstätt witch trials (1613–1630), the Würzburg witch trial (1626–1631), and the Bamberg witch trials (1626–1631).

In 1590, the North Berwick witch trials occurred in Scotland, and were of particular note as the king, James VI,

became involved himself. James had developed a fear that witches

planned to kill him after he suffered from storms while traveling to

Denmark in order to claim his bride, Anne, earlier that year. Returning to Scotland, the king heard of trials that were occurring in North Berwick, and ordered the suspects to be brought to him—he subsequently believed that a nobleman, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell,

was a witch, and after the latter fled in fear of his life, he was

outlawed as a traitor. The king subsequently set up royal commissions to

hunt down witches in his realm, recommending torture in dealing with

suspects, and in 1597, he wrote a book about the menace that witches

posed to society, entitled Daemonologie.

The more remote parts of Europe, as well as North America, were

reached by the witch panic later in the 17th-century, among them being

the Salzburg witch trials, the Swedish Torsåker witch trials and, somewhat later, in 1692, the Salem witch trials in New England.

Decline of the trials: 1650–1750

There had never been a lack of skepticism regarding the trials. In 1635, the authorities of the Roman Inquisition acknowledged its own trials had "found scarcely one trial conducted legally".

In the middle of the 17th century, the difficulty in proving witchcraft

according to the legal process contributed to the councilors of Rothenburg (German) following advice to treat witchcraft cases with caution.

Although the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of

Europe by the mid-17th century, they continued on the fringes of Europe

and in the American Colonies. In the Nordic countries, the late 17th

century saw the peak of the trials in a number of areas: the Torsåker witch trials of Sweden (1674), where 71 people were executed for witchcraft in a single day, the peak of witch hunting in Swedish Finland, and the Salzburg witch trials in Austria (where 139 people were executed from 1675 to 1690).

The 1692 Salem witch trials were a brief outburst of witch-phobia which occurred in the New World

when the practice was waning in Europe. In the 1690s, Winifred King

Benham and her daughter Winifred were thrice tried for witchcraft in Wallingford, Connecticut, the last of such trials in New England. Even though they were found innocent, they were compelled to leave Wallingford and settle in Staten Island, New York. In 1706, Grace Sherwood of Virginia was tried by ducking and jailed for allegedly being a witch.

Rationalist historians in the 18th century came to the opinion that the use of torture had resulted in erroneous testimony.

Witch trials became scant in the second half of the 17th century, and their growing disfavor eventually resulted in the British Witchcraft Act 1735, which formally ended witch-trials in Great Britain.

In France, scholars have found that with increased fiscal

capacity and a stronger central government, the witchcraft accusations

began to decline.

The witch trials that occurred there were symptomatic of a weak legal

system and "witches were most likely to be tried and convicted in

regions where magistrates departed from established legal statutes".

During the early 18th century, the practice subsided. Jane Wenham

was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in

1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. The last

execution for witchcraft in England took place in 1716, when Mary Hicks

and her daughter Elizabeth were hanged. Janet Horne was executed for witchcraft in Scotland in 1727. The Witchcraft Act of 1735

put an end to the traditional form of witchcraft as a legal offense in

Britain. Those accused under the new act were restricted to those that

pretended to be able to conjure spirits (generally being the most

dubious professional fortune tellers and mediums), and punishment was

light.

In Austria, Maria Theresa outlawed witch-burning and torture in 1768. The last capital trial, that of Maria Pauer occurred in 1750 in Salzburg, which was then outside the Austrian domain.

Sporadic witch-hunts after 1750

In

the later 18th century, witchcraft had ceased to be considered a

criminal offense throughout Europe, but there are a number of cases

which were not technically witch trials, but are suspected to have

involved belief in witches at least behind the scenes. Thus, in 1782, Anna Göldi was executed in Glarus, Switzerland, officially for the killing of her infant—a ruling at the time widely denounced throughout Switzerland and Germany as judicial murder. Like Anna Göldi, Barbara Zdunk was executed in 1811 in Prussia, not technically for witchcraft, but for arson. In Poland, the Doruchów witch trials

occurred in 1783, and the execution of two additional women for sorcery

in 1793, tried by a legal court, but with dubious legitimacy.

Despite the official ending of the trials for witchcraft, there

would still be occasional unofficial killings of those accused in parts

of Europe, such as was seen in the cases of Anna Klemens in Denmark (1800), Krystyna Ceynowa in Poland (1836), and Dummy, the Witch of Sible Hedingham

in England (1863). In France, there was sporadic violence and even

murder in the 1830s, with one woman reportedly burnt in a village square

in Nord.

In the 1830s, a prosecution for witchcraft was commenced against a man

in Fentress County, Tennessee, named either Joseph or William Stout,

based upon his alleged influence over the health of a young woman. The

case against the supposed witch was dismissed upon the failure of the

alleged victim, who had sworn out a warrant against him, to appear for

the trial. However, some of his other accusers were convicted on

criminal charges for their part in the matter, and various libel actions

were brought.

In 1895, Bridget Cleary

was beaten and burned to death by her husband in Ireland because he

suspected that fairies had taken the real Bridget and replaced her with a

witch.

The persecution of those believed to perform malevolent sorcery

against their neighbors continued into the 20th century. In 1997, two

Russian farmers killed a woman and injured five other members of her

family after believing that they had used folk magic against them.

It has been reported that more than 3,000 people were killed by lynch

mobs in Tanzania between 2005 and 2011 for allegedly being witches.

Procedures and punishments

Evidence

Peculiar

standards applied to witchcraft allowing certain types of evidence

"that are now ways relating Fact, and done many Years before." There was

no possibility to offer alibi

as a defense because witchcraft did not require the presence of the

accused at the scene. Witnesses were called to testify to motives and

effects because it was believed that witnessing the invisible force of

witchcraft was impossible: "half proofes are to be allowed, and are good

causes of suspicion".

Interrogations and torture

Various acts of torture

were used against accused witches to coerce confessions and cause them

to provide names of alleged co-conspirators. Most historians agree that

the majority of those persecuted in these witch trials were innocent of

any involvement in Devil worship.

The torture of witches began to increase in frequency after 1468, when

the Pope declared witchcraft to be "crimen exceptum" and thereby removed

all legal limits on the application of torture in cases where evidence

was difficult to find.

In Italy, an accused witch was deprived of sleep for periods up

to forty hours. This technique was also used in England, but without a

limitation on time.

Sexual humiliation was used, such as forced sitting on red-hot stools

with the claim that the accused woman would not perform sexual acts with

the devil. In most cases, those who endured the torture without confessing were released.

The use of torture has been identified as a key factor in converting the trial of one accused witch into a wider social panic, as those being tortured were more likely to accuse a wide array of other local individuals of also being witches.

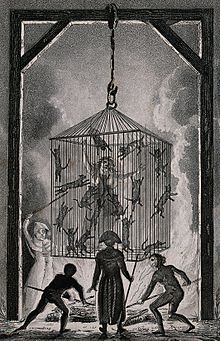

The burning of a French midwife in a cage filled with black cats

Punishments

A

variety of different punishments were employed for those found guilty

of witchcraft, including imprisonment, flogging, fines, or exile. The Old Testament's book of Exodus (22:18) states, "Thou shalt not permit a sorceress to live". Many faced capital punishment for witchcraft, either by burning at the stake, hanging, or beheading. Similarly, in New England, people convicted of witchcraft were hanged.

Estimates of the total number of executions

The scholarly consensus on the total number of executions for witchcraft ranges from 40,000 to 60,000

(not including unofficial lynchings of accused witches, which went

unrecorded but are nevertheless believed to have been somewhat rare in

the Early Modern period).

It would also have been the case that various individuals would have

died as a result of the unsanitary conditions of their imprisonment, but

again this is not recorded within the number of executions.

Attempts at estimating the total number of executions for

witchcraft have a history going back to the end of the period of

witch-hunts in the 18th century. A scholarly consensus only emerges in

the second half of the 20th century, and historical estimates vary

wildly depending on the method used. Early estimates tend to be highly

exaggerated, as they were still part of rhetorical arguments against the

persecution of witches rather than purely historical scholarship.

Notably, a figure of nine million victims was given by Gottfried Christian Voigt in 1784 in an argument criticizing Voltaire's estimate of "several hundred thousand" as too low. Voigt's number has shown remarkably resilient as an influential popular myth, surviving well into the 20th century, especially in feminist and neo-pagan literature. In the 19th century, some scholars were agnostic, for instance, Jacob Grimm (1844) talked of "countless" victims and Charles Mackay (1841) named "thousands upon thousands". By contrast, a popular news report of 1832 cited a number of 3,192 victims "in Great Britain alone".

In the early 20th century, some scholarly estimates on the number of

executions still ranged in the hundreds of thousands. The estimate was

only reliably placed below 100,000 in scholarship of the 1970s.

Causes and interpretations

The Witch, No. 1, c. 1892 lithograph by Joseph E. Baker

The Witch, No. 2, c. 1892 lithograph by Joseph E. Baker

The Witch, No. 3, c. 1892 lithograph by Joseph E. Baker

Regional differences

There

were many regional differences in the manner in which the witch trials

occurred. The trials themselves emerged sporadically, flaring up in some

areas but neighbouring areas remaining largely unaffected. In general, there seems to have been less witch-phobia in the papal lands of Italy and Spain in comparison to France and the Holy Roman Empire.

There was much regional variation within the British Isles. In Ireland, for example, there were few trials.

The

malefizhaus of Bamberg, Germany, where suspected witches were held and interrogated: 1627 engraving

There are particularly important differences between the English and

continental witch-hunting traditions. In England the use of torture was

rare and the methods far more restrained. The country formally permitted

it only when authorized by the monarch, and no more than 81 torture

warrants were issued (for all offenses) throughout English history. The death toll in Scotland dwarfed that of England.

It is also apparent from an episode of English history, that during the

civil war in the early 1640s, witch-hunters emerged, the most notorious

of whom was Matthew Hopkins from East Anglia and proclaimed himself the "Witchfinder General".

Italy has had fewer witchcraft accusations, and even fewer cases

where witch trials ended in execution. In 1542, the establishment of the

Roman Catholic Inquisition effectively restrained secular courts under

its influence from liberal application of torture and execution.

The methodological Instructio, which served as an "appropriate" manual

for witch hunting, cautioned against hasty convictions and careless

executions of the accused. In contrast with other parts of Europe,

trials by the Venetian Holy Office never saw conviction for the crime of

malevolent witchcraft, or "maleficio".

Because the notion of diabolical cults was not credible to either

popular culture or Catholic inquisitorial theology, mass accusations and

belief in Witches' Sabbath never took root in areas under such

inquisitorial influence.

The number of people tried for witchcraft between the years of 1500-1700 (by region)

Holy Roman Empire: 50,000

Poland: 15,000

Switzerland: 9,000

French Speaking Europe: 10,000

Spanish and Italian peninsulas: 10,000

Scandinavia: 4,000...

Socio-political turmoil

Various

suggestions have been made that the witch trials emerged as a response

to socio-political turmoil in the Early Modern world. One form of this

is that the prosecution of witches was a reaction to a disaster that had

befallen the community, such as crop failure, war, or disease.

For instance, Midelfort suggested that in southwestern Germany, war and

famine destabilised local communities, resulting in the witch

prosecutions of the 1620s.

Behringer also suggests an increase in witch prosecutions due to

socio-political destabilization, stressing the Little Ice Age's effects

on food shortages, and the subsequent use of witches as scapegoats for

consequences of climatic changes. The Little Ice Age, lasting from about 1300 to 1850, is characterized by temperatures and precipitation levels lower than the 1901–1960 average.

Historians such as Wolfgang Behringer, Emily Oster, and Hartmut Lehmann

argue that these cooling temperatures brought about crop failure, war,

and disease, and that witches were subsequently blamed for this turmoil.

Historical temperature indexes and witch trial data indicate that,

generally, as temperature decreased during this period, witch trials

increased.

Additionally, the peaks of witchcraft persecutions overlap with hunger

crises that occurred in 1570 and 1580, the latter lasting a decade.

Problematically for these theories, it has been highlighted that, in

that region, the witch hunts declined during the 1630s, at a time when

the communities living there were facing increased disaster as a result

of plague, famine, economic collapse, and the Thirty Years' War.

Furthermore, this scenario would clearly not offer a universal

explanation, for trials also took place in areas which were free from

war, famine, or pestilence. Additionally, these theories—particularly Behringer's —have been labeled as oversimplified.

Although there is evidence that the Little Ice Age and subsequent

famine and disease was likely a contributing factor to increase in witch

persecution, Durrant argues that one cannot make a direct link between

these problems and witch persecutions in all contexts.

Moreover, the average age at first marriage

had gradually risen by the late sixteenth century; the population had

stabilized after a period of growth, and availability of jobs and land

had lessened. In the last decades of the century, the age at marriage

had climbed to averages of 25 for women and 27 for men in England and

the Low Countries, as more people married later or remained unmarried

due to lack of money or resources and a decline in living standards, and

these averages remained high for nearly two centuries and averages

across Northwestern Europe had done likewise. The convents were closed during the Protestant Reformation,

which displaced many nuns. Many communities saw the proportion of

unmarried women climb from less than 10% to 20% and in some cases as

high as 30%, whom few communities knew how to accommodate economically.

Miguel (2003) argues that witch killings may be a process of

eliminating the financial burdens of a family or society, via

elimination of the older women that need to be fed, and an increase in unmarried women would enhance this process.

Catholic versus Protestant conflict

The English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper

advocated the idea that the witch trials emerged as part of the

conflicts between Roman Catholics and Protestants in Early Modern

Europe. A 2017 study in the Economic Journal,

examining "more than 43,000 people tried for witchcraft across 21

European countries over a period of five-and-a-half centuries", found

that "more intense religious-market contestation led to more intense

witch-trial activity. And, compared to religious-market contestation,

the factors that existing hypotheses claim were important for

witch-trial activity—weather, income, and state capacity—were not."

Until recently, this theory received limited support from other experts in the subject.

This is because there is little evidence that either Roman Catholics

were accusing Protestants of witchcraft, or that Protestants were

accusing Roman Catholics.

Furthermore, the witch trials regularly occurred in regions with little

or no inter-denominational strife, and which were largely religiously

homogenous, such as Essex, Lowland Scotland, Geneva, Venice, and the Spanish Basque Country.

There is also some evidence, particularly from the Holy Roman Empire,

in which adjacent Roman Catholic and Protestant territories were

exchanging information on alleged local witches, viewing them as a

common threat to both.

Additionally, many prosecutions were instigated not by the religious or

secular authorities, but by popular demands from within the population,

thus making it less likely that there were specific

inter-denominational reasons behind the accusations.

The more recent research from the 2017 study in the Economic Journal

argues that both Catholics and Protestants used the hunt for witches,

regardless of the witch's denomination, in competitive efforts to expand

power and influence.

In south-western Germany, between 1561 and 1670, there were 480

witch trials. Of the 480 trials that took place in southwestern Germany,

317 occurred in Catholic areas and 163 in Protestant territories.

During the period from 1561 to 1670, at least 3,229 persons were

executed for witchcraft in the German Southwest. Of this number, 702

were tried and executed in Protestant territories and 2,527 in Catholic

territories.

Translation from the Hebrew: Witch or poisoner?

It

has been argued that a translation choice in the King James Bible

justified "horrific human rights violations and fuel[ed] the epidemic of

witchcraft accusations and persecution across the globe". The translation issue concerned Exodus 22:18, "do not suffer a ...[either 1) poisoner or

2) witch] ...to live." Both the King James and the Geneva Bible, which

precedes the King James version by 51 years, chose the word "witch" for

this verse. The proper translation and definition of the Hebrew word in

Exodus 22:18 was much debated during the time of the trials and

witch-phobia.

1970s folklore emphasis

From the 1970s onward, there was a "massive explosion of scholarly enthusiasm" for the study of the Early Modern witch trials. This was partly because scholars from a variety of different disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, cultural studies, philosophy, philosophy of science, criminology, literary theory, and feminist theory, all began to investigate the phenomenon and brought different insights to the subject.

This was accompanied by analysis of the trial records and the

socio-cultural contexts on which they emerged, allowing for varied

understanding of the trials.

Functionalism

Inspired

by ethnographically recorded witch trials that anthropologists observed

happening in non-European parts of the world, various historians have

sought a functional explanation for the Early Modern witch trials,

thereby suggesting the social functions that the trials played within

their communities.

These studies have illustrated how accusations of witchcraft have

played a role in releasing social tensions or in facilitating the

termination of personal relationships that have become undesirable to

one party.

Feminist interpretations

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, various feminist interpretations of the witch trials have been made and published. One of the earliest individuals to do so was the American Matilda Joslyn Gage, a writer who was deeply involved in the first-wave feminist movement for women's suffrage. In 1893, she published the book Woman, Church and State,

which was criticized as "written in a tearing hurry and in time

snatched from a political activism which left no space for original

research". Likely influenced by the works of Jules Michelet about the Witch-Cult, she claimed that the witches persecuted in the Early Modern period were pagan priestesses adhering to an ancient religion venerating a Great Goddess.

She also repeated the erroneous statement, taken from the works of

several German authors, that nine million people had been killed in the

witch hunt. The United States has become the centre of development for these feminist interpretations.

In 1973, two American second-wave feminists, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English,

published an extended pamphlet in which they put forward the idea that

the women persecuted had been the traditional healers and midwives of

the community, who were being deliberately eliminated by the male

medical establishment.

This theory disregarded the fact that the majority of those persecuted

were neither healers nor midwives, and that in various parts of Europe

these individuals were commonly among those encouraging the

persecutions. In 1994, Anne Llewellyn Barstow published her book Witchcraze,

which was later described by Scarre and Callow as "perhaps the most

successful" attempt to portray the trials as a systematic male attack on

women.

Other feminist historians have rejected this interpretation of events; historian Diane Purkiss

described it as "not politically helpful" because it constantly

portrays women as "helpless victims of patriarchy" and thus does not aid

them in contemporary feminist struggles. She also condemned it for factual inaccuracy by highlighting that radical feminists adhering to it ignore the historicity

of their claims, instead promoting it because it is perceived as

authorising the continued struggle against patriarchal society.

She asserted that many radical feminists nonetheless clung to it

because of its "mythic significance" and firmly delineated structure

between the oppressor and the oppressed.

Male and Female conflict and reaction to earlier feminist studies

An estimated 75% to 85% of those accused in the early modern witch trials were women, and there is certainly evidence of misogyny

on the part of those persecuting witches, evident from quotes such as

"[It is] not unreasonable that this scum of humanity, [witches], should

be drawn chiefly from the feminine sex" (Nicholas Rémy,

c. 1595) or "The Devil uses them so, because he knows that women love

carnal pleasures, and he means to bind them to his allegiance by such

agreeable provocations." Scholar Kurt Baschwitz, in his first monography on the subject (in Dutch, 1948), mentions this aspect of the witch trials even as "a war against old women".

Nevertheless, it has been argued that the supposedly misogynistic

agenda of works on witchcraft has been greatly exaggerated, based on

the selective repetition of a few relevant passages of the Malleus maleficarum.

There are various reasons as to why this was the case. In Early Modern

Europe, it was widely believed that women were less intelligent than men

and more susceptible to sin.

Many modern scholars argue that the witch hunts cannot be explained

simplistically as an expression of male misogyny, as indeed women were

frequently accused by other women,

to the point that witch-hunts, at least at the local level of villages,

have been described as having been driven primarily by "women's

quarrels". Especially at the margins of Europe, in Iceland, Finland, Estonia, and Russia, the majority of those accused were male.

Barstow (1994) claimed that a combination of factors, including

the greater value placed on men as workers in the increasingly

wage-oriented economy, and a greater fear of women as inherently evil,

loaded the scales against women, even when the charges against them were

identical to those against men.

Thurston (2001) saw this as a part of the general misogyny of the Late

Medieval and Early Modern periods, which had increased during what he

described as "the persecuting culture" from which it had been in the

Early Medieval. Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger,

in a 1982 publication, speculated that witch-hunts targeted women

skilled in midwifery specifically in an attempt to extinguish knowledge

about birth control and "repopulate Europe" after the population catastrophe of the Black Death.

Were there any sort of witches?

Throughout

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the common belief among

educated sectors of the European populace was that there had never been

any genuine cult of witches and that all those persecuted and executed

as such had been innocent of the crime.

However, at this time various scholars suggested that there had been a

real cult that had been persecuted by the Christian authorities, and

that it had had pre-Christian origins. The first to advance this theory

was the German Professor of Criminal Law Karl Ernst Jarcke of the University of Berlin,

who put forward the idea in 1828; he suggested that witchcraft had been

a pre-Christian German religion that had degenerated into Satanism.

Jarcke's ideas were picked up by the German historian Franz Josef Mone

in 1839, although he argued that the cult's origins were Greek rather

than Germanic.

In 1862, the Frenchman Jules Michelet published La Sorciere,

in which he put forth the idea that the witches had been following a

pagan religion. The theory achieved greater attention when it was taken

up by the Egyptologist Margaret Murray, who published both The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) and The God of the Witches

(1931) in which she claimed that the witches had been following a

pre-Christian religion which she termed "the Witch-Cult" and "Ritual

Witchcraft".

Murray claimed that this faith was devoted to a pagan Horned God and involved the celebration of four Witches' Sabbaths each year: Halloween, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh. However, the majority of scholarly reviews of Murray's work produced at the time were largely critical, and her books never received support from experts in the Early Modern witch trials.

Instead, from her early publications onward many of her ideas were

challenged by those who highlighted her "factual errors and

methodological failings".

We Neopagans now face a crisis. As new data appeared, historians

altered their theories to account for it. We have not. Therefore an

enormous gap has opened between the academic and the 'average' Pagan

view of witchcraft. We continue to use of out-dated and poor writers,

like Margaret Murray, Montague Summers, Gerald Gardner, and Jules Michelet.

We avoid the somewhat dull academic texts that present solid research,

preferring sensational writers who play to our emotions.

—Jenny Gibbons (1998)

However, the publication of the Murray thesis in the Encyclopaedia Britannica made it accessible to "journalists, film-makers popular novelists and thriller writers", who adopted it "enthusiastically". Influencing works of literature, it inspired writings by Aldous Huxley and Robert Graves.

Subsequently, in 1939, an English occultist named Gerald Gardner claimed to have been initiated into a surviving group of the pagan Witch-Cult known as the New Forest Coven,

although modern historical investigation has led scholars to believe

that this coven was not ancient as Gardner believed, but was instead

founded in the 1920s or 1930s by occultists wishing to fashion a revived

Witch-Cult based upon Murray's theories. Taking this New Forest Coven's beliefs and practices as a basis, Gardner went on to found Gardnerian Wicca, one of the most prominent traditions in the contemporary pagan religion now known as Wicca, which revolves around the worship of a Horned God and Goddess, the celebration of festivals known as Sabbats, and the practice of ritual magic. He also went on to write several books about the historical Witch-Cult, Witchcraft Today (1954) and The Meaning of Witchcraft

(1959), and in these books, Gardner used the phrase "the burning times"

in reference to the European and North American witch trials.

In the early 20th century, a number of individuals and groups

emerged in Europe, primarily Britain, and subsequently the United States

as well, claiming to be the surviving remnants of the pagan Witch-Cult

described in the works of Margaret Murray. The first of these actually

appeared in the last few years of the 19th century, being a manuscript

that American folklorist Charles Leland claimed he had been given by a woman who was a member of a group of witches worshipping the god Lucifer and goddess Diana in Tuscany, Italy. He published the work in 1899 as Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches.

Whilst historians and folklorists have accepted that there are

folkloric elements to the gospel, none have accepted it as being the

text of a genuine Tuscan religious group, and believe it to be of

late-nineteenth-century composition.

Wiccans extended claims regarding the witch-cult in various ways,

for instance by utilising the British folklore associating witches with

prehistoric sites to assert that the witch-cult used to use such

locations for religious rites, in doing so legitimising contemporary

Wiccan use of them.

By the 1990s, many Wiccans had come to recognise the inaccuracy of the

witch-cult theory and had accepted it as a mythological origin story.