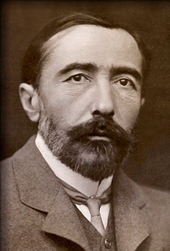

| Author | Joseph Conrad |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novella |

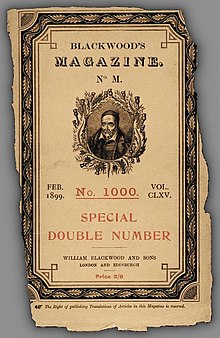

| Published | 1899 serial; 1902 book |

| Publisher | Blackwood's Magazine |

| Preceded by | The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897) |

| Followed by | Lord Jim (1900) |

| Text | Heart of Darkness at Wikisource |

Heart of Darkness (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad. It tells the story of Charles Marlow, a sailor who takes on an assignment from a Belgian trading company as a ferry-boat captain in the African interior. The novel is widely regarded as a critique of European colonial rule in Africa, whilst also examining the themes of power dynamics and morality. Although Conrad does not name the river where the narrative takes place, at the time of writing the Congo Free State, the location of the large and economically important Congo River, was a private colony of Belgium's King Leopold II. Marlow is given a text by Kurtz, an ivory trader working on a trading station far up the river, who has "gone native" and is the object of Marlow's expedition.

Central to Conrad's work is the idea that there is little difference between "civilised people" and "savages." Heart of Darkness implicitly comments on imperialism and racism. The novella's setting provides the frame for Marlow's story of his obsession with the successful ivory trader Kurtz. Conrad offers parallels between London ("the greatest town on earth") and Africa as places of darkness.

Originally issued as a three-part serial story in Blackwood's Magazine to celebrate the thousandth edition of the magazine, Heart of Darkness has been widely re-published and translated into many languages. It provided the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Heart of Darkness 67th on their list of the 100 best novels in English of the twentieth century.

Composition and publication

In 1890, at the age of 32, Conrad was appointed by a Belgian trading company to serve on one of its steamers. While sailing up the Congo River from one station to another, the captain became ill and Conrad assumed command. He guided the ship up the tributary Lualaba River to the trading company's innermost station, Kindu, in Eastern Congo Free State; Marlow has similar experiences to the author.

When Conrad began to write the novella, eight years after returning from Africa, he drew inspiration from his travel journals. He described Heart of Darkness as "a wild story" of a journalist who becomes manager of a station in the (African) interior and makes himself worshipped by a tribe of savages. The tale was first published as a three-part serial, in February, March and April 1899, in Blackwood's Magazine (February 1899 was the magazine's 1000th issue: special edition). In 1902 Heart of Darkness was included in the book Youth: a Narrative, and Two Other Stories, published on 13 November 1902 by William Blackwood.

The volume consisted of Youth: a Narrative, Heart of Darkness and The End of the Tether in that order. In 1917, for future editions of the book, Conrad wrote an "Author's Note" where he, after denying any "unity of artistic purpose" underlying the collection, discusses each of the three stories and makes light commentary on Marlow, the narrator of the tales within the first two stories. He said Marlow first appeared in Youth.

On 31 May 1902, in a letter to William Blackwood, Conrad remarked,

I call your own kind self to witness ... the last pages of Heart of Darkness where the interview of the man and the girl locks in—as it were—the whole 30000 words of narrative description into one suggestive view of a whole phase of life and makes of that story something quite on another plane than an anecdote of a man who went mad in the Centre of Africa.

There have been many proposed sources for the character of the antagonist, Kurtz. Georges-Antoine Klein, an agent who became ill and died aboard Conrad's steamer, is proposed by literary critics as a basis for Kurtz. The principal figures involved in the disastrous "rear column" of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition have also been identified as likely sources, including column leader Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, slave trader Tippu Tip and the expedition leader, Welsh explorer Henry Morton Stanley. Conrad's biographer Norman Sherry judged that Arthur Hodister (1847–1892), a Belgian solitary but successful trader, who spoke three Congolese languages and was venerated by Congolese to the point of deification, served as the main model, while later scholars have refuted this hypothesis. Adam Hochschild, in King Leopold's Ghost, believes that the Belgian soldier Léon Rom influenced the character. Peter Firchow mentions the possibility that Kurtz is a composite, modelled on various figures present in the Congo Free State at the time as well as on Conrad's imagining of what they might have had in common.

A corrective impulse to impose one's rule characterizes Kurtz's writings which were discovered by Marlow during his journey, where he rants on behalf of the so-called "International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" about his supposedly altruistic and sentimental reasons to civilise the "savages"; one document ends with a dark proclamation to "Exterminate all the brutes!". The "International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs" is interpreted as a sarcastic reference to one of the participants at the Berlin Conference, the International Association of the Congo (also called "International Congo Society"). The predecessor to this organisation was the "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa".

Synopsis

Charles Marlow, the narrator, tells his story to friends aboard Nellie, a boat anchored on the River Thames near Gravesend, of how he became captain of a river steamboat for an ivory trading company. As a child, Marlow was fascinated by "the blank spaces" on maps, particularly Africa. The image of a river on the map particularly fascinated Marlow.

In a flashback, Marlow makes his way to Africa, taking passage on a steamer. He departs 30 mi (50 km) up the river where his company's station is. Work on a railway is going on. Marlow explores a narrow ravine, and is horrified to find himself in a place full of diseased Africans who worked on the railroad and are now dying.

Marlow must wait for ten days in the company's devastated Outer Station. Marlow meets the company's chief accountant, who tells him of a Mr. Kurtz, who is in charge of a very important trading post, and a widely respected, first-class agent. The accountant predicts that Kurtz will go far.

Marlow departs with sixty men to travel to the Central Station, where the steamboat that he is to captain is based. At the station, he learns that his steamboat has been wrecked in an accident. The general manager informs Marlow that he could not wait for Marlow to arrive, and tells him of a rumour that Kurtz is ill. Marlow fishes his boat out of the river and spends months repairing it. Delayed by the lack of tools and replacement parts, Marlow is frustrated by the time it takes to perform the repairs. He learns that Kurtz is resented, not admired, by the manager. Once underway, the journey to Kurtz's station takes two months.

The journey pauses for the night about 8 miles (13 km) below the Inner Station. In the morning the boat is enveloped by a thick fog. The steamboat is later attacked by a barrage of arrows, and the helmsman is killed. Marlow sounds the steam whistle repeatedly, frightening the attackers away.

After landing at Kurtz's station, a man boards the steamboat: a Russian wanderer who strayed into Kurtz's camp. Marlow learns that the natives worship Kurtz, and that he has been very ill of late. The Russian tells of how Kurtz opened his mind and seems to admire Kurtz even for his power and his willingness to use it. Marlow suggests that Kurtz has gone mad.

Marlow observes the station and sees a row of posts topped with the severed heads of natives. Around the corner of the house, the manager appears with the pilgrims, bearing a gaunt and ghost-like Kurtz. The area fills with natives ready for battle, but Kurtz shouts something from the stretcher and the natives retreat. The pilgrims carry Kurtz to the steamer and lay him in one of the cabins. The manager tells Marlow that Kurtz has harmed the company's business in the region, that his methods are "unsound". The Russian reveals that Kurtz believes the company wants to kill him, and Marlow confirms that hangings were discussed.

After midnight, Marlow discovers that Kurtz has returned to shore. He finds Kurtz crawling back to the station house. Marlow threatens to harm Kurtz if he raises an alarm, but Kurtz only laments that he had not accomplished more. The next day they prepare to journey back down the river.

Kurtz's health worsens during the trip and Marlow becomes increasingly ill. The steamboat breaks down, and while stopped for repairs, Kurtz gives Marlow a packet of papers, including his commissioned report and a photograph, telling him to keep them away from the manager. When Marlow next speaks with him, Kurtz is near death; Marlow hears him weakly whisper, "The horror! The horror!" A short while later, the "manager's boy" announces to the rest of the crew that Kurtz has died. The next day Marlow pays little attention to the pilgrims as they bury "something" in a muddy hole. He falls very ill, himself near death.

Upon his return to Europe, Marlow is embittered and contemptuous of the "civilised" world. Several callers come to retrieve the papers Kurtz entrusted to him, but Marlow withholds them or offers papers he knows they have no interest in. He gives Kurtz's report to a journalist, for publication if he sees fit. Marlow is left with some personal letters and a photograph of Kurtz's fiancée. When Marlow visits her, she is deep in mourning although it has been more than a year since Kurtz's death. She presses Marlow for information, asking him to repeat Kurtz's final words. Marlow tells her that Kurtz's final word was her name.

Critical reception

Literary critic Harold Bloom wrote that Heart of Darkness had been analysed more than any other work of literature that is studied in universities and colleges, which he attributed to Conrad's "unique propensity for ambiguity," but it was not a big success during Conrad's life. When it was published as a single volume in 1902 with two novellas, "Youth" and "The End of the Tether", it received the least commentary from critics. F. R. Leavis referred to Heart of Darkness as a "minor work" and criticised its "adjectival insistence upon inexpressible and incomprehensible mystery". Conrad did not consider it to be particularly notable; but by the 1960s it was a standard assignment in many college and high school English courses.

In King Leopold's Ghost (1998), Adam Hochschild wrote that literary scholars have made too much of the psychological aspects of Heart of Darkness, while paying scant attention to Conrad's accurate recounting of the horror arising from the methods and effects of colonialism in the Congo Free State. "Heart of Darkness is experience ... pushed a little (and only very little) beyond the actual facts of the case". Other critiques include Hugh Curtler's Achebe on Conrad: Racism and Greatness in Heart of Darkness (1997). The French philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe called Heart of Darkness "one of the greatest texts of Western literature" and used Conrad's tale for a reflection on "The Horror of the West".

Heart of Darkness is criticised in postcolonial studies, particularly by Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe. In his 1975 public lecture "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness", Achebe described Conrad's novella as "an offensive and deplorable book" that de-humanised Africans. Achebe argued that Conrad, "blinkered ... with xenophobia", incorrectly depicted Africa as the antithesis of Europe and civilisation, ignoring the artistic accomplishments of the Fang people who lived in the Congo River basin at the time of the book's publication. He argued that the book promoted and continues to promote a prejudiced image of Africa that "depersonalises a portion of the human race" and concluded that it should not be considered a great work of art.

Achebe's critics argue that he fails to distinguish Marlow's view from Conrad's, which results in very clumsy interpretations of the novella. In their view, Conrad portrays Africans sympathetically and their plight tragically, and refers sarcastically to, and condemns outright, the supposedly noble aims of European colonists, thereby demonstrating his skepticism about the moral superiority of European men. Ending a passage that describes the condition of chained, emaciated slaves, Marlow remarks: "After all, I also was a part of the great cause of these high and just proceedings." Some observers assert that Conrad, whose native country had been conquered by imperial powers, empathised by default with other subjugated peoples. Jeffrey Meyers notes that Conrad, like his acquaintance Roger Casement, "was one of the first men to question the Western notion of progress, a dominant idea in Europe from the Renaissance to the Great War, to attack the hypocritical justification of colonialism and to reveal... the savage degradation of the white man in Africa." Likewise, E.D. Morel, who led international opposition to King Leopold II's rule in the Congo, saw Conrad's Heart of Darkness as a condemnation of colonial brutality and referred to the novella as "the most powerful thing written on the subject."

Conrad scholar Peter Firchow writes that "nowhere in the novel does Conrad or any of his narrators, personified or otherwise, claim superiority on the part of Europeans on the grounds of alleged genetic or biological difference". If Conrad or his novel is racist, it is only in a weak sense, since Heart of Darkness acknowledges racial distinctions "but does not suggest an essential superiority" of any group. Achebe's reading of Heart of Darkness can be (and has been) challenged by a reading of Conrad's other African story, "An Outpost of Progress", which has an omniscient narrator, rather than the embodied narrator, Marlow. Some younger scholars, such as Masood Ashraf Raja, have also suggested that if we read Conrad beyond Heart of Darkness, especially his Malay novels, racism can be further complicated by foregrounding Conrad's positive representation of Muslims.

In 2003, Motswana scholar Peter Mwikisa concluded the book was "the great lost opportunity to depict dialogue between Africa and Europe". Zimbabwean scholar Rino Zhuwarara, however, broadly agreed with Achebe, though considered it important to be "sensitised to how peoples of other nations perceive Africa". The novelist Caryl Phillips stated in 2003 that: "Achebe is right; to the African reader the price of Conrad's eloquent denunciation of colonisation is the recycling of racist notions of the 'dark' continent and her people. Those of us who are not from Africa may be prepared to pay this price, but this price is far too high for Achebe".

In his 1983 criticism, the British academic Cedric Watts criticizes the insinuation in Achebe's critique—the premise that only black people may accurately analyse and assess the novella, as well as mentioning that Achebe's critique falls into self-contradictory arguments regarding Conrad's writing style, both praising and denouncing it at times. Stan Galloway writes, in a comparison of Heart of Darkness with Jungle Tales of Tarzan, "The inhabitants [of both works], whether antagonists or compatriots, were clearly imaginary and meant to represent a particular fictive cipher and not a particular African people". More recent critics have stressed that the "continuities" between Conrad and Achebe are profound and that a form of "postcolonial mimesis" ties the two authors.

Adaptations and influences

Radio and stage

Orson Welles adapted and starred in Heart of Darkness in a CBS Radio broadcast on 6 November 1938 as part of his series, The Mercury Theatre on the Air. In 1939, Welles adapted the story for his first film for RKO Pictures, writing a screenplay with John Houseman. The story was adapted to focus on the rise of a fascist dictator. Welles intended to play Marlow and Kurtz and it was to be entirely filmed as a POV from Marlow's eyes. Welles even filmed a short presentation film illustrating his intent. It is reportedly lost. The film's prologue to be read by Welles said "You aren't going to see this picture - this picture is going to happen to you." The project was never realised; one reason given was the loss of European markets after the outbreak of war. Welles still hoped to produce the film when he presented another radio adaptation of the story as his first program as producer-star of the CBS radio series This Is My Best. Welles scholar Bret Wood called the broadcast of 13 March 1945, "the closest representation of the film Welles might have made, crippled, of course, by the absence of the story's visual elements (which were so meticulously designed) and the half-hour length of the broadcast."

In 1991, Australian author/playwright Larry Buttrose wrote and staged a theatrical adaptation titled Kurtz with the Crossroads Theatre Company, Sydney. The play was announced to be broadcast as a radio play to Australian radio audiences in August 2011 by the Vision Australia Radio Network, and also by the RPH – Radio Print Handicapped Network across Australia.

In 2011, composer Tarik O'Regan and librettist Tom Phillips adapted an opera of the same name, which premiered at the Linbury Theatre of the Royal Opera House in London. A suite for orchestra and narrator was subsequently extrapolated from it.

In 2015, an adaption of Welles' screenplay by Jamie Lloyd and Laurence Bowen aired on BBC Radio 4. The production starred James McAvoy as Marlow.

Film and television

The CBS television anthology Playhouse 90 aired a loose 90-minute adaptation in 1958, Heart of Darkness (Playhouse 90). This version, written by Stewart Stern, uses the encounter between Marlow (Roddy McDowall) and Kurtz (Boris Karloff) as its final act, and adds a backstory in which Marlow had been Kurtz's adopted son. The cast includes Inga Swenson and Eartha Kitt.

Perhaps the best known adaptation is Francis Ford Coppola's 1979 film Apocalypse Now, based on the screenplay by John Milius, which moves the story from the Congo to Vietnam and Cambodia during the Vietnam War. In Apocalypse Now, Martin Sheen stars as Captain Benjamin L. Willard, a US Army Captain assigned to "terminate the command" of Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando. A film documenting the production, titled Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, showed some of the difficulties which director Coppola faced making the film, which resembled some of the novella's themes.

On 13 March 1993, TNT aired a new version of the story, directed by Nicolas Roeg, starring Tim Roth as Marlow and John Malkovich as Kurtz.

James Gray's 2019 science fiction film Ad Astra is loosely inspired by the events of the novel. It features Brad Pitt as an astronaut travelling to the edge of the Solar System to confront and potentially kill his father (Tommy Lee Jones), who has gone rogue.

In 2020, African Apocalypse, a documentary film directed and produced by Rob Lemkin and featuring Femi Nylander portrays a journey from Oxford, England to Niger on the trail of a colonial killer called Captain Paul Voulet. Voulet's descent into barbarity mirrors that of Kurtz in Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Nylander discovers Voulet's massacres happened at exactly the same time that Conrad wrote his book in 1899. It was broadcast by the BBC in May 2021 as an episode of the Arena documentary series.

Video games

The video game Far Cry 2, released on 21 October 2008, is a loose modernised adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The player assumes the role of a mercenary operating in Africa whose task it is to kill an arms dealer, the elusive "Jackal". The last area of the game is called "The Heart of Darkness".

Spec Ops: The Line, released on 26 June 2012, is a direct modernised adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The player assumes the role of special-ops agent Martin Walker as he and his team search Dubai for survivors in the aftermath of catastrophic sandstorms that left the city without contact to the outside world. The character John Konrad, who replaces the character Kurtz, is a reference to Joseph Conrad.

Victoria II, a grand strategy game produced by Paradox Interactive, launched an expansion pack titled "Heart of Darkness" on 16 April 2013, which revamped the game's colonial system, and naval warfare.

World of Warcraft's seventh expansion, Battle for Azeroth, has a dark, swampy zone named Nazmir that makes many references to both Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now. Examples include the sub zone "Heart of Darkness" and a quest of the same name that mentions a character named "Captain Conrad", amongst others.

Literature

T. S. Eliot's 1925 poem The Hollow Men quotes, as its first epigraph, a line from Heart of Darkness: "Mistah Kurtz – he dead." Eliot had planned to use a quotation from the climax of the tale as the epigraph for The Waste Land, but Ezra Pound advised against it. Eliot said of the quote that "it is much the most appropriate I can find, and somewhat elucidative." Biographer Peter Ackroyd suggested that the passage inspired or at least anticipated the central theme of the poem.

The novel Hearts of Darkness by Paul Lawrence moves the events of the novel to England in the mid-17th century. Marlow's journey into the jungle becomes a journey by the narrator, Harry Lytle, and his friend Davy Dowling out of London and towards Shyam, a plague-stricken town that has descended into cruelty and barbarism, loosely modelled on real-life Eyam. While Marlow must return to civilisation with Kurtz, Lytle and Dowling are searching for the spy James Josselin. Like Kurtz, Josselin's reputation is immense and the protagonists are well-acquainted with his accomplishments by the time they meet him.

Poet Yedda Morrison's 2012 book Darkness erases Conrad's novella, "whiting out" his text so that only images of the natural world remain.

James Reich's Mistah Kurtz! A Prelude to Heart of Darkness presents the early life of Kurtz, his appointment to his station in the Congo and his messianic disintegration in a novel that dovetails with the conclusion of Conrad's novella. Reich's novel is premised upon the papers Kurtz leaves to Marlow at the end of Heart of Darkness.

In Josef Škvorecký's 1984 novel The Engineer of Human Souls, Kurtz is seen as the epitome of exterminatory colonialism and, there and elsewhere, Škvorecký emphasises the importance of Conrad's concern with Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe.

Timothy Findley's 1993 novel Headhunter is an extensive adaptation that reimagines Kurtz and Marlow as psychiatrists in Toronto. The novel begins: "On a winter's day, while a blizzard raged through the streets of Toronto, Lilah Kemp inadvertently set Kurtz free from page 92 of Heart of Darkness."

Another literary work with an acknowledged debt to Heart of Darkness is Wilson Harris' 1960 postcolonial novel Palace of the Peacock.

J. G. Ballard's 1962 climate fiction novel The Drowned World includes many similarities to Conrad's novella. However, Ballard said he had read nothing by Conrad before writing the novel, prompting literary critic Robert S. Lehman to remark that "the novel's allusion to Conrad works nicely, even if it is not really an allusion to Conrad".

Robert Silverberg's 1970 novel Downward to the Earth uses themes and characters based on Heart of Darkness set on the alien world of Belzagor.