Zoroaster 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚𐬎𐬱𐬙𐬭𐬀 Zaraθuštra | |

|---|---|

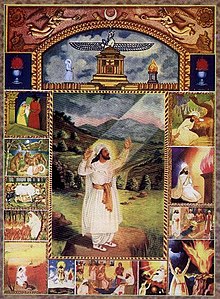

19th-century Indian Zoroastrian perception of Zoroaster derived from a figure that appears in a 4th-century sculpture at Taq-e Bostan in South-Western Iran. The original is now believed to be either a representation of Mithra or Hvare-khshaeta. | |

| Venerated in | Zoroastrianism Manichaeism Baháʼí Faith Mithraism Ahmadiyya |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

Zoroaster (/ˈzɒroʊæstər/, UK also /ˌzɒroʊˈæstər/; Greek: Ζωροάστρης, Zōroastrēs), also known as Zarathustra (/ˌzærəˈθuːstrə/, UK also /ˌzɑːrə-/; Avestan: 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚𐬎𐬱𐬙𐬭𐬀, Zaraθuštra), Zarathushtra Spitama or Ashu Zarathushtra (Modern Persian: زرتشت, Zartosht), was an ancient Iranian prophet (spiritual leader) who founded what is now known as Zoroastrianism. His teachings challenged the existing traditions of the Indo-Iranian religion and inaugurated a movement that eventually became the dominant religion in Ancient Persia. He was a native speaker of Old Avestan and lived in the eastern part of the Iranian Plateau, but his exact birthplace is uncertain.

There is no scholarly consensus on when he lived. Some scholars, using linguistic and socio-cultural evidence, suggest a dating to somewhere in the second millennium BC. Other scholars date him in the 7th and 6th century BC as a near-contemporary of Cyrus the Great and Darius I. Zoroastrianism eventually became the official religion of Ancient Persia and its distant subdivisions from the 6th century BC to the 7th century AD. Zoroaster is credited with authorship of the Gathas as well as the Yasna Haptanghaiti, hymns composed in his native dialect, Old Avestan and which comprise the core of Zoroastrian thinking. Most of his life is known from these texts. By any modern standard of historiography, no evidence can place him into a fixed period and the historicization surrounding him may be a part of a trend from before the 10th century AD that historicizes legends and myths.

Name and etymology

Zoroaster's name in his native language, Avestan, was probably Zaraθuštra. His English name, "Zoroaster", derives from a later (5th century BC) Greek transcription, Zōroastrēs (Ζωροάστρης), as used in Xanthus's Lydiaca (Fragment 32) and in Plato's First Alcibiades (122a1). This form appears subsequently in the Latin Zōroastrēs and, in later Greek orthographies, as Ζωροάστρις Zōroastris. The Greek form of the name appears to be based on a phonetic transliteration or semantic substitution of Avestan zaraθ- with the Greek ζωρός zōros (literally "undiluted") and the Avestan -uštra with ἄστρον astron ("star").

In Avestan, Zaraθuštra is generally accepted to derive from an Old Iranian *Zaratuštra-; The element half of the name (-uštra-) is thought to be the Indo-Iranian root for "camel", with the entire name meaning "he who can manage camels". Reconstructions from later Iranian languages—particularly from the Middle Persian (300 BC) Zardusht, which is the form that the name took in the 9th- to 12th-century Zoroastrian texts—suggest that *Zaratuštra- might be a zero-grade form of *Zarantuštra-. Subject then to whether Zaraθuštra derives from *Zarantuštra- or from *Zaratuštra-, several interpretations have been proposed.

If Zarantuštra is the original form, it may mean "with old/aging camels", related to Avestic zarant- (cf. Pashto zōṛ and Ossetian zœrond, "old"; Middle Persian zāl, "old"):

- "with angry/furious camels": from Avestan *zarant-, "angry, furious".

- "who is driving camels" or "who is fostering/cherishing camels": related to Avestan zarš-, "to drag".

- Mayrhofer (1977) proposed an etymology of "who is desiring camels" or "longing for camels" and related to Vedic Sanskrit har-, "to like", and perhaps (though ambiguous) also to Avestan zara-.

- "with yellow camels": parallel to Younger Avestan zairi-.

The interpretation of the -θ- (/θ/) in Avestan zaraθuštra was for a time itself subjected to heated debate because the -θ- is an irregular development: As a rule, *zarat- (a first element that ends in a dental consonant) should have Avestan zarat- or zarat̰- as a development from it. Why this is not so for zaraθuštra has not yet been determined. Notwithstanding the phonetic irregularity, that Avestan zaraθuštra with its -θ- was linguistically an actual form is shown by later attestations reflecting the same basis. All present-day, Iranian-language variants of his name derive from the Middle Iranian variants of Zarθošt, which, in turn, all reflect Avestan's fricative -θ-.

In Middle Persian, the name is 𐭦𐭫𐭲𐭥𐭱𐭲 Zardu(x)št, in Parthian Zarhušt, in Manichaean Middle Persian Zrdrwšt, in Early New Persian Zardušt, and in modern (New Persian), the name is زرتشت Zartosht.

The name is attested in Classical Armenian sources as Zradašt (often with the variant Zradešt). The most important of these testimonies were provided by the Armenian authors Eznik of Kolb, Elishe, and Movses Khorenatsi. The spelling Zradašt was formed through an older form which started with *zur-, a fact which the German Iranologist Friedrich Carl Andreas (1846–1930) used as evidence for a Middle Persian spoken form *Zur(a)dušt. Based on this assumption, Andreas even went so far to form conclusions from this also for the Avestan form of the name. However, the modern Iranologist Rüdiger Schmitt rejects Andreas's assumption, and states that the older form which started with *zur- was just influenced by Armenian zur ("wrong, unjust, idle"), which therefore means that "the name must have been reinterpreted in an anti-Zoroastrian sense by the Armenian Christians". Furthermore, Schmitt adds: "it cannot be excluded, that the (Parthian or) Middle Persian form, which the Armenians took over (Zaradušt or the like), was merely metathesized to pre-Arm. *Zuradašt".

Date

There is no consensus on the dating of Zoroaster; the Avesta gives no direct information about it, while historical sources are conflicting. Some scholars base their date reconstruction on the Proto-Indo-Iranian language and Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, and thus his origin is considered to have been somewhere in northeastern Iran and sometime between 1500 and 500 BC.

Some scholars such as Mary Boyce (who dated Zoroaster to somewhere between 1700 and 1000 BC) used linguistic and socio-cultural evidence to place Zoroaster between 1500 and 1000 BC (or 1200 and 900 BC). The basis of this theory is primarily proposed on linguistic similarities between the Old Avestan language of the Zoroastrian Gathas and the Sanskrit of the Rigveda (c. 1700–1100 BC), a collection of early Vedic hymns. Both texts are considered to have a common archaic Indo-Iranian origin. The Gathas portray an ancient Stone-Bronze Age bipartite society of warrior-herdsmen and priests (compared to Bronze tripartite society; some conjecture that it depicts the Yaz culture), and that it is thus implausible that the Gathas and Rigveda could have been composed more than a few centuries apart. These scholars suggest that Zoroaster lived in an isolated tribe or composed the Gathas before the 1200–1000 BC migration by the Iranians from the steppe to the Iranian Plateau. The shortfall of the argument is the vague comparison, and the archaic language of Gathas does not necessarily indicate time difference.

Other scholars propose a period between 7th and 6th century BC, for example, c. 650–600 BC or 559–522 BC. The latest possible date is the mid 6th century BC, at the time of Achaemenid Empire's Darius I, or his predecessor Cyrus the Great. This date gains credence mainly from attempts to connect figures in Zoroastrian texts to historical personages; thus some have postulated that the mythical Vishtaspa who appears in an account of Zoroaster's life was Darius I's father, also named Vishtaspa (or Hystaspes in Greek). However, if this were true, it seems unlikely that the Avesta would not mention that Vishtaspa's son became the ruler of the Persian Empire, or that this key fact about Darius's father would not be mentioned in the Behistun Inscription. It is also possible that Darius I's father was named in honor of the Zoroastrian patron, indicating possible Zoroastrian faith by Arsames.

Classical scholarship in the 6th to 4th century BC believed he existed six thousand years before Xerxes I's invasion of Greece in 480 BC (Xanthus, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Hermippus), which is a possible misunderstanding of the Zoroastrian four cycles of 3000 years i.e. 12,000 years. This belief is recorded by Diogenes Laërtius, and variant readings could place it six hundred years before Xerxes I, somewhere before 1000 BC. However, Diogenes also mentions Hermodorus's belief that Zoroaster lived five thousand years before the Trojan War, which would mean he lived around 6200 BC. The 10th-century Suda provides a date of "500 years before Plato" in the late 10th century BC. Pliny the Elder cited Eudoxus who also placed his death six thousand years before Plato, c. 6300 BC. Other pseudo-historical constructions are those of Aristoxenus who recorded Zaratas the Chaldeaean to have taught Pythagoras in Babylon, or lived at the time of mythological Ninus and Semiramis. According to Pliny the Elder, there were two Zoroasters. The first lived thousands of years ago, while the second accompanied Xerxes I in the invasion of Greece in 480 BC. Some scholars propose that the chronological calculation for Zoroaster was developed by Persian magi in the 4th century BC, and as the early Greeks learned about him from the Achaemenids, this indicates they did not regard him as a contemporary of Cyrus the Great, but as a remote figure.

Some later pseudo-historical and Zoroastrian sources (the Bundahishn, which references a date "258 years before Alexander") place Zoroaster in the 6th century BC, which coincided with the accounts by Ammianus Marcellinus from the 4th century CE. The traditional Zoroastrian date originates in the period immediately following Alexander the Great's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BC. The Seleucid rulers who gained power following Alexander's death instituted an "Age of Alexander" as the new calendrical epoch. This did not appeal to the Zoroastrian priesthood who then attempted to establish an "Age of Zoroaster". To do so, they needed to establish when Zoroaster had lived, which they accomplished by (erroneous, according to Mary Boyce some even identified Cyrus with Vishtaspa) counting back the length of successive generations, until they concluded that Zoroaster must have lived "258 years before Alexander". This estimate then re-appeared in the 9th- to 12th-century Arabic and Pahlavi texts of Zoroastrian tradition, like the 10th century Al-Masudi who cited a prophecy from a lost Avestan book in which Zoroaster foretold the Empire's destruction in three hundred years, but the religion would last for a thousand years.

Place

The birthplace of Zoroaster is also unknown, and the language of the Gathas is not similar to the proposed north-western and north-eastern regional dialects of Persia. It is also suggested that he was born in one of the two areas and later lived in the other area.

Yasna 9 and 17 cite the Ditya River in Airyanem Vaējah (Middle Persian Ērān Wēj) as Zoroaster's home and the scene of his first appearance. The Avesta (both Old and Younger portions) does not mention the Achaemenids or of any West Iranian tribes such as the Medes, Persians, or even Parthians. The Farvardin Yasht refers to some Iranian peoples that are unknown in the Greek and Achaemenid sources about the 6th and 5th century BC Eastern Iran. The Vendidad contain seventeen regional names, most of which are located in north-eastern and eastern Iran.

However, in Yasna 59.18, the zaraθuštrotema, or supreme head of the Zoroastrian priesthood, is said to reside in 'Ragha' (Badakhshan). In the 9th- to 12th-century Middle Persian texts of Zoroastrian tradition, this 'Ragha' and with many other places appear as locations in Western Iran. While the land of Media does not figure at all in the Avesta (the westernmost location noted in scripture is Arachosia), the Būndahišn, or "Primordial Creation," (20.32 and 24.15) puts Ragha in Media (medieval Rai). However, in Avestan, Ragha is simply a toponym meaning "plain, hillside."

Apart from these indications in Middle Persian sources that are open to interpretations, there are a number of other sources. The Greek and Latin sources are divided on the birthplace of Zarathustra. There are many Greek accounts of Zarathustra, referred usually as Persian or Perso-Median Zoroaster; Ctesias located him in Bactria, Diodorus Siculus placed him among Ariaspai (in Sistan), Cephalion and Justin suggest east of greater Iran whereas Pliny and Origen suggest west of Iran as his birthplace. Moreover, they have the suggestion that there has been more than one Zoroaster.

On the other hand, in post-Islamic sources Shahrastani (1086–1153) an Iranian writer originally from Shahristān, present-day Turkmenistan, proposed that Zoroaster's father was from Atropatene (also in Medea) and his mother was from Rey. Coming from a reputed scholar of religions, this was a serious blow for the various regions who all claimed that Zoroaster originated from their homelands, some of which then decided that Zoroaster must then have then been buried in their regions or composed his Gathas there or preached there. Also Arabic sources of the same period and the same region of historical Persia consider Azerbaijan as the birthplace of Zarathustra.

By the late 20th century, most scholars had settled on an origin in eastern Greater Iran. Gnoli proposed Sistan, Baluchistan (though in a much wider scope than the present-day province) as the homeland of Zoroastrianism; Frye voted for Bactria and Chorasmia; Khlopin suggests the Tedzen Delta in present-day Turkmenistan. Sarianidi considered the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex region as "the native land of the Zoroastrians and, probably, of Zoroaster himself." Boyce includes the steppes to the west from the Volga. The medieval "from Media" hypothesis is no longer taken seriously, and Zaehner has even suggested that this was a Magi-mediated issue to garner legitimacy, but this has been likewise rejected by Gershevitch and others.

The 2005 Encyclopedia Iranica article on the history of Zoroastrianism summarizes the issue with "while there is general agreement that he did not live in western Iran, attempts to locate him in specific regions of eastern Iran, including Central Asia, remain tentative".

Life

Zoroaster is recorded as the son of Pourušaspa of the Spitamans or Spitamids (Avestan spit mean "brilliant" or "white"; some argue that Spitama was a remote progenitor) family, and Dugdōw, while his great-grandfather was Haēčataspa. All the names appear appropriate to the nomadic tradition. His father's name means "possessing gray horses" (with the word aspa meaning horse), while his mother's means "milkmaid". According to the tradition, he had four brothers, two older and two younger, whose names are given in much later Pahlavi work.

The training for priesthood probably started very early around seven years of age. He became a priest probably around the age of fifteen, and according to Gathas, he gained knowledge from other teachers and personal experience from traveling when he left his parents at age twenty. By the age of thirty, he experienced a revelation during a spring festival; on the river bank he saw a shining Being, who revealed himself as Vohu Manah (Good Purpose) and taught him about Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord) and five other radiant figures. Zoroaster soon became aware of the existence of two primal Spirits, the second being Angra Mainyu (Destructive Spirit), with opposing concepts of Asha (order) and Druj (deception). Thus he decided to spend his life teaching people to seek Asha. He received further revelations and saw a vision of the seven Amesha Spenta, and his teachings were collected in the Gathas and the Avesta.

Eventually, at the age of about forty-two, he received the patronage of queen Hutaosa and a ruler named Vishtaspa, an early adherent of Zoroastrianism (possibly from Bactria according to the Shahnameh). Zoroaster's teaching about individual judgment, Heaven and Hell, the resurrection of the body, the Last Judgment, and everlasting life for the reunited soul and body, among other things, became borrowings in the Abrahamic religions, but they lost the context of the original teaching.

According to the tradition, he lived for many years after Vishtaspa's conversion, managed to establish a faithful community, and married three times. His first two wives bore him three sons, Isat Vâstra, Urvatat Nara, and Hvare Chithra, and three daughters, Freni, Thriti, and Pouruchista. His third wife, Hvōvi, was childless. Zoroaster died when he was 77 years and 40 days old. The later Pahlavi sources like Shahnameh, instead claim that an obscure conflict with Tuiryas people led to his death, murdered by a karapan (a priest of the old religion) named Brādrēs.

Cypress of Kashmar

The Cypress of Kashmar is a mythical cypress tree of legendary beauty and gargantuan dimensions. It is said to have sprung from a branch brought by Zoroaster from Paradise and to have stood in today's Kashmar in northeastern Iran and to have been planted by Zoroaster in honor of the conversion of King Vishtaspa to Zoroastrianism. According to the Iranian physicist and historian Zakariya al-Qazwini King Vishtaspa had been a patron of Zoroaster who planted the tree himself. In his ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt ("The Wonders of Creatures and the Marvels of Creation"), he further describes how the Al-Mutawakkil in 247 AH (861 AD) caused the mighty cypress to be felled, and then transported it across Iran, to be used for beams in his new palace at Samarra. Before, he wanted the tree to be reconstructed before his eyes. This was done in spite of protests by the Iranians, who offered a very great sum of money to save the tree. Al-Mutawakkil never saw the cypress, because he was murdered by a Turkic soldier (possibly in the employ of his son) on the night when it arrived on the banks of the Tigris.

Influences

In Christianity

In Islam

A number of parallels have been drawn between Zoroastrian teachings and Islam. Such parallels include the evident similarities between Amesha Spenta and the archangel Gabriel, praying five times a day, covering one's head during prayer, and the mention of Thamud and Iram of the Pillars in the Quran. These may also indicate the vast influence of the Achaemenid Empire on the development of either religion.

The Sabaeans, who believed in free will coincident with Zoroastrians, are also mentioned in the Quran.

Muslim scholastic views

Like the Greeks of classical antiquity, Islamic tradition understands Zoroaster to be the founding prophet of the Magians (via Aramaic, Arabic Majus, collective Majusya). The 11th-century Cordoban Ibn Hazm (Zahiri school) contends that Kitabi "of the Book" cannot apply in light of the Zoroastrian assertion that their books were destroyed by Alexander. Citing the authority of the 8th-century al-Kalbi, the 9th- and 10th-century Sunni historian al-Tabari (I, 648) reports that Zaradusht bin Isfiman (an Arabic adaptation of "Zarathustra Spitama") was an inhabitant of Israel and a servant of one of the disciples of the prophet Jeremiah. According to this tale, Zaradusht defrauded his master, who cursed him, causing him to become leprous (cf. Elisha's servant Gehazi in Jewish Scripture).

The apostate Zaradusht then eventually made his way to Balkh (present day Afghanistan) where he converted Bishtasb (i.e. Vishtaspa), who in turn compelled his subjects to adopt the religion of the Magians. Recalling other tradition, al-Tabari (I, 681–683) recounts that Zaradusht accompanied a Jewish prophet to Bishtasb/Vishtaspa. Upon their arrival, Zaradusht translated the sage's Hebrew teachings for the king and so convinced him to convert (Tabari also notes that they had previously been Sabis) to the Magian religion.

The 12th-century heresiographer al-Shahrastani describes the Majusiya into three sects, the Kayumarthiya, the Zurwaniya and the Zaradushtiya, among which Al-Shahrastani asserts that only the last of the three were properly followers of Zoroaster. As regards the recognition of a prophet, Zoroaster has said: "They ask you as to how should they recognize a prophet and believe him to be true in what he says; tell them what he knows the others do not, and he shall tell you even what lies hidden in your nature; he shall be able to tell you whatever you ask him and he shall perform such things which others cannot perform." (Namah Shat Vakhshur Zartust, .5–7. 50–54)

Ahmadiyya view

The Ahmadiyya Community views Zoroaster as a Prophet of Allah and describe the expressions of the all-good Ahura Mazda and evil Ahriman as merely referring to the coexistence of forces of good and evil enabling humans to exercise free will.

In Manichaeism

Manichaeism considered Zoroaster to be a figure (along with the Buddha and Jesus) in a line of prophets of which Mani (216–276) was the culmination. Zoroaster's ethical dualism is—to an extent—incorporated in Mani's doctrine, which viewed the world as being locked in an epic battle between opposing forces of good and evil. Manicheanism also incorporated other elements of Zoroastrian tradition, particularly the names of supernatural beings; however, many of these other Zoroastrian elements are either not part of Zoroaster's own teachings or are used quite differently from how they are used in Zoroastrianism.

In the Baháʼí Faith

Zoroaster appears in the Baháʼí Faith as a "Manifestation of God", one of a line of prophets who have progressively revealed the Word of God to a gradually maturing humanity. Zoroaster thus shares an exalted station with Abraham, Moses, Krishna, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb, and the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, Bahá'u'lláh. Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Baháʼí Faith in the first half of the 20th century, saw Bahá'u'lláh as the fulfillment of a post-Sassanid Zoroastrian prophecy that saw a return of Sassanid emperor Bahram: Shoghi Effendi also stated that Zoroaster lived roughly 1000 years before Jesus.

Philosophy

In the Gathas, Zoroaster sees the human condition as the mental struggle between aša and druj. The cardinal concept of aša—which is highly nuanced and only vaguely translatable—is at the foundation of all Zoroastrian doctrine, including that of Ahura Mazda (who is aša), creation (that is aša), existence (that is aša), and as the condition for free will.

The purpose of humankind, like that of all other creation, is to sustain and align itself to aša. For humankind, this occurs through active ethical participation in life, ritual, and the exercise of constructive/good thoughts, words and deeds.

Elements of Zoroastrian philosophy entered the West through their influence on Judaism and Platonism and have been identified as one of the key early events in the development of philosophy. Among the classic Greek philosophers, Heraclitus is often referred to as inspired by Zoroaster's thinking.

In 2005, the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy ranked Zarathustra as first in the chronology of philosophers. Zarathustra's impact lingers today due in part to the system of religious ethics he founded called Mazdayasna. The word Mazdayasna is Avestan and is translated as "Worship of Wisdom/Mazda" in English. The encyclopedia Natural History (Pliny) claims that Zoroastrians later educated the Greeks who, starting with Pythagoras, used a similar term, philosophy, or "love of wisdom" to describe the search for ultimate truth.

Zoroaster emphasized the freedom of the individual to choose right or wrong and individual responsibility for one's deeds. This personal choice to accept aša and shun druj is one's own decision and not a dictate of Ahura Mazda. For Zoroaster, by thinking good thoughts, saying good words, and doing good deeds (e.g. assisting the needy, doing good works, or conducting good rituals) we increase aša in the world and in ourselves, celebrate the divine order, and we come a step closer on the everlasting road to Frashokereti. Thus, we are not the slaves or servants of Ahura Mazda, but we can make a personal choice to be co-workers, thereby perfecting the world as saoshyants ("world-perfecters") and ourselves and eventually achieve the status of an Ashavan ("master of Asha").

Iconography

Although a few recent depictions of Zoroaster show him performing some deed of legend, in general the portrayals merely present him in white vestments (which are also worn by present-day Zoroastrian priests). He often is seen holding a collection of unbound rods or twigs, known as a baresman (Avestan; Middle Persian barsom), which is generally considered to be another symbol of priesthood, or with a book in hand, which may be interpreted to be the Avesta. Alternatively, he appears with a mace, the varza—usually stylized as a steel rod crowned by a bull's head—that priests carry in their installation ceremony. In other depictions he appears with a raised hand and thoughtfully lifted finger, as if to make a point.

Zoroaster is rarely depicted as looking directly at the viewer; instead, he appears to be looking slightly upwards, as if beseeching. Zoroaster is almost always depicted with a beard, this along with other factors bearing similarities to 19th-century portraits of Jesus.

A common variant of the Zoroaster images derives from a Sassanid-era rock-face carving. In this depiction at Taq-e Bostan, a figure is seen to preside over the coronation of Ardashir I or II. The figure is standing on a lotus, with a baresman in hand and with a gloriole around his head. Until the 1920s, this figure was commonly thought to be a depiction of Zoroaster, but in recent years is more commonly interpreted to be a depiction of Mithra. Among the most famous of the European depictions of Zoroaster is that of the figure in Raphael's 1509 The School of Athens. In it, Zoroaster and Ptolemy are having a discussion in the lower right corner. The prophet is holding a star-studded globe.

Depiction of Zoroaster in Clavis Artis, an alchemy manuscript published in Germany in the late 17th or early 18th century and pseudoepigraphically attributed to Zoroaster

Western civilization

In classical antiquity

The Greeks—in the Hellenistic sense of the term—had an understanding of Zoroaster as expressed by Plutarch, Diogenes Laertius, and Agathias that saw him, at the core, to be the "prophet and founder of the religion of the Iranian peoples," Beck notes that "the rest was mostly fantasy". Zoroaster was set in the ancient past, six to seven millennia before the Common Era, and was described as a king of Bactria or a Babylonian (or teacher of Babylonians), and with a biography typical of a Neopythagorean sage, i.e. having a mission preceded by ascetic withdrawal and enlightenment. However, at first mentioned in the context of dualism, in Moralia, Plutarch presents Zoroaster as "Zaratras," not realizing the two to be the same, and he is described as a "teacher of Pythagoras".

Zoroaster has also been described as a sorcerer-astrologer – the creator of both magic and astrology. Deriving from that image, and reinforcing it, was a "mass of literature" attributed to him and that circulated the Mediterranean world from the 3rd century BC to the end of antiquity and beyond.

The language of that literature was predominantly Greek, though at one stage or another various parts of it passed through Aramaic, Syriac, Coptic or Latin. Its ethos and cultural matrix was likewise Hellenistic, and "the ascription of literature to sources beyond that political, cultural and temporal framework represents a bid for authority and a fount of legitimizing "alien wisdom". Zoroaster and the magi did not compose it, but their names sanctioned it." The attributions to "exotic" names (not restricted to magians) conferred an "authority of a remote and revelatory wisdom."

Among the named works attributed to "Zoroaster" is a treatise On Nature (Peri physeos), which appears to have originally constituted four volumes (i.e. papyrus rolls). The framework is a retelling of Plato's Myth of Er, with Zoroaster taking the place of the original hero. While Porphyry imagined Pythagoras listening to Zoroaster's discourse, On Nature has the sun in middle position, which was how it was understood in the 3rd century. In contrast, Plato's 4th-century BC version had the sun in second place above the moon. Colotes accused Plato of plagiarizing Zoroaster, and Heraclides Ponticus wrote a text titled Zoroaster based on his perception of "Zoroastrian" philosophy, in order to express his disagreement with Plato on natural philosophy. With respect to substance and content in On Nature only two facts are known: that it was crammed with astrological speculations, and that Necessity (Ananké) was mentioned by name and that she was in the air.

Pliny the Elder names Zoroaster as the inventor of magic (Natural History 30.2.3). "However, a principle of the division of labor appears to have spared Zoroaster most of the responsibility for introducing the dark arts to the Greek and Roman worlds." That "dubious honor" went to the "fabulous magus, Ostanes, to whom most of the pseudepigraphic magical literature was attributed." Although Pliny calls him the inventor of magic, the Roman does not provide a "magician's persona" for him. Moreover, the little "magical" teaching that is ascribed to Zoroaster is actually very late, with the very earliest example being from the 14th century.

Association with astrology according to Roger Beck, were based on his Babylonian origin, and Zoroaster's Greek name was identified at first with star-worshiping (astrothytes "star sacrificer") and, with the Zo-, even as the living star. Later, an even more elaborate mythoetymology evolved: Zoroaster died by the living (zo-) flux (ro-) of fire from the star (astr-) which he himself had invoked, and even, that the stars killed him in revenge for having been restrained by him.

The alternate Greek name for Zoroaster was Zaratras or Zaratas/Zaradas/Zaratos. Pythagoreans considered the mathematicians to have studied with Zoroaster in Babylonia. Lydus, in On the Months, attributes the creation of the seven-day week to "the Babylonians in the circle of Zoroaster and Hystaspes," and who did so because there were seven planets. The Suda's chapter on astronomia notes that the Babylonians learned their astrology from Zoroaster. Lucian of Samosata, in Mennipus 6, reports deciding to journey to Babylon "to ask one of the magi, Zoroaster's disciples and successors," for their opinion.

While the division along the lines of Zoroaster/astrology and Ostanes/magic is an "oversimplification, the descriptions do at least indicate what the works are not"; they were not expressions of Zoroastrian doctrine, they were not even expressions of what the Greeks and Romans "imagined the doctrines of Zoroastrianism to have been" [emphases in the original]. The assembled fragments do not even show noticeable commonality of outlook and teaching among the several authors who wrote under each name.

Almost all Zoroastrian pseudepigrapha is now lost, and of the attested texts—with only one exception—only fragments have survived. Pliny's 2nd- or 3rd-century attribution of "two million lines" to Zoroaster suggest that (even if exaggeration and duplicates are taken into consideration) a formidable pseudepigraphic corpus once existed at the Library of Alexandria. This corpus can safely be assumed to be pseudepigrapha because no one before Pliny refers to literature by "Zoroaster", and on the authority of the 2nd-century Galen of Pergamon and from a 6th-century commentator on Aristotle it is known that the acquisition policies of well-endowed royal libraries created a market for fabricating manuscripts of famous and ancient authors.

The exception to the fragmentary evidence (i.e. reiteration of passages in works of other authors) is a complete Coptic tractate titled Zostrianos (after the first-person narrator) discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945. A three-line cryptogram in the colophones following the 131-page treatise identify the work as "words of truth of Zostrianos. God of Truth [logos]. Words of Zoroaster." Invoking a "God of Truth" might seem Zoroastrian, but there is otherwise "nothing noticeably Zoroastrian" about the text and "in content, style, ethos and intention, its affinities are entirely with the congeners among the Gnostic tractates."

Another work circulating under the name of "Zoroaster" was the Asteroskopita (or Apotelesmatika), and which ran to five volumes (i.e. papyrus rolls). The title and fragments suggest that it was an astrological handbook, "albeit a very varied one, for the making of predictions." A third text attributed to Zoroaster is On Virtue of Stones (Peri lithon timion), of which nothing is known other than its extent (one volume) and that pseudo-Zoroaster sang it (from which Cumont and Bidez conclude that it was in verse). Numerous other fragments preserved in the works of other authors are attributed to "Zoroaster," but the titles of those books are not mentioned.

These pseudepigraphic texts aside, some authors did draw on a few genuinely Zoroastrian ideas. The Oracles of Hystaspes, by "Hystaspes", another prominent magian pseudo-author, is a set of prophecies distinguished from other Zoroastrian pseudepigrapha in that it draws on real Zoroastrian sources. Some allusions are more difficult to assess: in the same text that attributes the invention of magic to Zoroaster, Pliny states that Zoroaster laughed on the day of his birth, although in an earlier place, Pliny had sworn in the name of Hercules that no child had ever done so before the 40th day from his birth. This notion of Zoroaster's laughter (like that of "two million verses") also appears in the 9th– to 11th-century texts of genuine Zoroastrian tradition, and for a time it was assumed that the origin of those myths lay with indigenous sources. Pliny also records that Zoroaster's head had pulsated so strongly that it repelled the hand when laid upon it, a presage of his future wisdom. The Iranians were however just as familiar with the Greek writers, and the provenance of other descriptions are clear. For instance, Plutarch's description of its dualistic theologies reads thus: "Others call the better of these a god and his rival a daemon, as, for example, Zoroaster the Magus, who lived, so they record, five thousand years before the siege of Troy. He used to call the one Horomazes and the other Areimanius".

In the modern era

The earliest recorded references to Zoroaster in English literature occur in the writings of the physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne who asserted in his Religio Medici (1643)

- I believe, besides Zoroaster, there were divers that writ before Moses, who notwithstanding have suffered the common fate of time.

In his The Garden of Cyrus (1658) Browne's study of comparative religion led him to speculate-

- And if Zoroaster were either Cham, Chus, or Mizraim, they were early proficients therein, who left (as Pliny delivereth) a work of Agriculture.

The Oxford English Dictionary attributes the English poet Lord Byron as the first to allude to the Zoroastrian religion in 1811 when stating-

- I would sooner be a Paulican, Manichean, Spinozist, Gentile, Pyrrohonian, Zoroastrian, than any one of the seventy-two villainous sects that are tearing each other to pieces for the love of the Lord.

In E. T. A. Hoffmann's novel Klein Zaches, genannt Zinnober (1819), the mage Prosper Alpanus states that Professor Zoroaster was his teacher.

In his seminal work Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra) (1885) the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche uses the native Iranian name Zarathustra which has a significant meaning as he had used the familiar Greek-Latin name in his earlier works. It is believed that Nietzsche invents a characterization of Zarathustra as the mouthpiece for Nietzsche's own ideas about morality.

The Austrian composer Richard Strauss's large-scale tone-poem Also sprach Zarathustra (1896) was inspired by Nietzsche's book.

A sculpture of Zoroaster by Edward Clarke Potter, representing ancient Persian judicial wisdom and dating to 1896, towers over the Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State at East 25th Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan. A sculpture of Zoroaster appears with other prominent religious figures on the south side of the exterior of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel on the campus of the University of Chicago.

The protagonist and narrator of Gore Vidal's 1981 novel Creation is described to be the grandson of Zoroaster.