From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Mathematical models can project how infectious diseases progress to show the likely outcome of an epidemic (including in plants) and help inform public health and plant health interventions. Models use basic assumptions or collected statistics along with mathematics to find parameters for various infectious diseases and use those parameters to calculate the effects of different interventions, like mass vaccination

programs. The modelling can help decide which intervention(s) to avoid

and which to trial, or can predict future growth patterns, etc.

History

The

modeling of infectious diseases is a tool that has been used to study

the mechanisms by which diseases spread, to predict the future course of

an outbreak and to evaluate strategies to control an epidemic.

The first scientist who systematically tried to quantify causes of death was John Graunt in his book Natural and Political Observations made upon the Bills of Mortality,

in 1662. The bills he studied were listings of numbers and causes of

deaths published weekly. Graunt's analysis of causes of death is

considered the beginning of the "theory of competing risks" which

according to Daley and Gani is "a theory that is now well established among modern epidemiologists".

The earliest account of mathematical modelling of spread of disease was carried out in 1760 by Daniel Bernoulli. Trained as a physician, Bernoulli created a mathematical model to defend the practice of inoculating against smallpox. The calculations from this model showed that universal inoculation against smallpox would increase the life expectancy from 26 years 7 months to 29 years 9 months. Daniel Bernoulli's work preceded the modern understanding of germ theory.

In the early 20th century, William Hamer and Ronald Ross applied the law of mass action to explain epidemic behaviour.

The 1920s saw the emergence of compartmental models. The Kermack–McKendrick epidemic model (1927) and the Reed–Frost epidemic model (1928) both describe the relationship between susceptible, infected and immune

individuals in a population. The Kermack–McKendrick epidemic model was

successful in predicting the behavior of outbreaks very similar to that

observed in many recorded epidemics.

Recently, agent-based models (ABMs) have been used in exchange for simpler compartmental models.

For example, epidemiological ABMs have been used to inform public

health (nonpharmaceutical) interventions against the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Epidemiological ABMs, in spite of their complexity and requiring high

computational power, have been criticized for simplifying and

unrealistic assumptions.

Still, they can be useful in informing decisions regarding mitigation

and suppression measures in cases when ABMs are accurately calibrated.

Assumptions

Models

are only as good as the assumptions on which they are based. If a model

makes predictions that are out of line with observed results and the

mathematics is correct, the initial assumptions must change to make the

model useful.

- Rectangular and stationary age distribution, i.e., everybody in the population lives to age L and then dies, and for each age (up to L)

there is the same number of people in the population. This is often

well-justified for developed countries where there is a low infant

mortality and much of the population lives to the life expectancy.

- Homogeneous mixing of the population, i.e., individuals of the population under scrutiny assort and make contact at random and do not mix mostly in a smaller subgroup. This assumption is rarely justified because social structure

is widespread. For example, most people in London only make contact

with other Londoners. Further, within London then there are smaller

subgroups, such as the Turkish community or teenagers (just to give two

examples), who mix with each other more than people outside their group.

However, homogeneous mixing is a standard assumption to make the

mathematics tractable.

Types of epidemic models

Stochastic

"Stochastic"

means being or having a random variable. A stochastic model is a tool

for estimating probability distributions of potential outcomes by

allowing for random variation in one or more inputs over time.

Stochastic models depend on the chance variations in risk of exposure,

disease and other illness dynamics. Statistical agent-level disease

dissemination in small or large populations can be determined by

stochastic methods.

Deterministic

When

dealing with large populations, as in the case of tuberculosis,

deterministic or compartmental mathematical models are often used. In a

deterministic model, individuals in the population are assigned to

different subgroups or compartments, each representing a specific stage

of the epidemic.

The transition rates from one class to another are mathematically

expressed as derivatives, hence the model is formulated using

differential equations. While building such models, it must be assumed

that the population size in a compartment is differentiable with respect

to time and that the epidemic process is deterministic. In other words,

the changes in population of a compartment can be calculated using only

the history that was used to develop the model.

Sub-exponential growth

A

common explanation for the growth of epidemics holds that 1 person

infects 2, those 2 infect 4 and so on and so on with the number of

infected doubling every generation.

It is analogous to a game of tag

where 1 person tags 2, those 2 tag 4 others who've never been tagged

and so on. As this game progresses it becomes increasing frenetic as the

tagged run past the previously tagged to hunt down those who have never

been tagged.

Thus this model of an epidemic leads to a curve that grows exponentially until it crashes to zero as all the population have been infected. i.e. no herd immunity and no peak and gradual decline as seen in reality.

A better analogy is a game of roulette.

Consider a wheel made of only red and black pockets, spin the wheel and

roll a ball.

The rules of the game are that if a ball lands in a red or black pocket

then the pocket turns green and, on the next spin, an extra ball is

rolled. If, instead, a ball lands in a green pocket then it is removed

from play.

The game is played until there are no balls left to roll at which point

there might have been exponential growth observed but it is highly

improbable.

Taking the average of a number of games and it is expected

that the initial growth is sub-exponential and that, at the end of the

game, not all of the pockets will be green which corresponds to herd

immunity.

Reproduction number

The basic reproduction number (denoted by R0)

is a measure of how transferable a disease is. It is the average number

of people that a single infectious person will infect over the course

of their infection. This quantity determines whether the infection will

increase sub-exponentially, die out, or remain constant: if R0 > 1, then each person on average infects more than one other person so the disease will spread; if R0 < 1, then each person infects fewer than one person on average so the disease will die out; and if R0 = 1, then each person will infect on average exactly one other person, so the disease will become endemic: it will move throughout the population but not increase or decrease.

Endemic steady state

An infectious disease is said to be endemic

when it can be sustained in a population without the need for external

inputs. This means that, on average, each infected person is infecting exactly one other person (any more and the number of people infected will grow sub-exponentially and there will be an epidemic, any less and the disease will die out). In mathematical terms, that is:

The basic reproduction number (R0)

of the disease, assuming everyone is susceptible, multiplied by the

proportion of the population that is actually susceptible (S)

must be one (since those who are not susceptible do not feature in our

calculations as they cannot contract the disease). Notice that this

relation means that for a disease to be in the endemic steady state,

the higher the basic reproduction number, the lower the proportion of

the population susceptible must be, and vice versa. This expression has

limitations concerning the susceptibility proportion, e.g. the R0 equals 0.5 implicates S has to be 2, however this proportion exceeds the population size.

Assume the rectangular stationary age distribution and let also

the ages of infection have the same distribution for each birth year.

Let the average age of infection be A, for instance when individuals younger than A are susceptible and those older than A

are immune (or infectious). Then it can be shown by an easy argument

that the proportion of the population that is susceptible is given by:

We reiterate that L is the age at which in this model every

individual is assumed to die. But the mathematical definition of the

endemic steady state can be rearranged to give:

Therefore, due to the transitive property:

This provides a simple way to estimate the parameter R0 using easily available data.

For a population with an exponential age distribution,

This allows for the basic reproduction number of a disease given A and L in either type of population distribution.

Compartmental models in epidemiology

Compartmental models are formulated as Markov chains.

A classic compartmental model in epidemiology is the SIR model, which

may be used as a simple model for modeling epidemics. Multiple other

types of compartmental models are also employed.

The SIR model

Diagram of the SIR model with initial values

, and rates for infection

and for recovery

Animation of the SIR model with initial values

, and rate of recovery

. The animation shows the effect of reducing the rate of infection from

to

. If there is no medicine or vaccination available, it is only possible to reduce the infection rate (often referred to as "

flattening the curve") by appropriate measures such as social distancing.

In 1927, W. O. Kermack and A. G. McKendrick created a model in which

they considered a fixed population with only three compartments:

susceptible,  ; infected,

; infected,  ; and recovered,

; and recovered,  . The compartments used for this model consist of three classes:

. The compartments used for this model consist of three classes:

is used to represent the individuals not yet infected with the disease

at time t, or those susceptible to the disease of the population.

is used to represent the individuals not yet infected with the disease

at time t, or those susceptible to the disease of the population. denotes the individuals of the population who have been infected with

the disease and are capable of spreading the disease to those in the

susceptible category.

denotes the individuals of the population who have been infected with

the disease and are capable of spreading the disease to those in the

susceptible category. is the compartment used for the individuals of the population who have

been infected and then removed from the disease, either due to

immunization or due to death. Those in this category are not able to be

infected again or to transmit the infection to others.

is the compartment used for the individuals of the population who have

been infected and then removed from the disease, either due to

immunization or due to death. Those in this category are not able to be

infected again or to transmit the infection to others.

Other compartmental models

There

are many modifications of the SIR model, including those that include

births and deaths, where upon recovery there is no immunity (SIS model),

where immunity lasts only for a short period of time (SIRS), where

there is a latent period of the disease where the person is not

infectious (SEIS and SEIR), and where infants can be born with immunity (MSIR).

Infectious disease dynamics

Mathematical models need to integrate the increasing volume of data being generated on host-pathogen interactions. Many theoretical studies of the population dynamics, structure and evolution of infectious diseases of plants and animals, including humans, are concerned with this problem. Research topics include:

Mathematics of mass vaccination

If the proportion of the population that is immune exceeds the herd immunity

level for the disease, then the disease can no longer persist in the

population and its transmission dies out. Thus, a disease can be

eliminated from a population if enough individuals are immune due to

either vaccination or recovery from prior exposure to disease. For

example, smallpox eradication, with the last wild case in 1977, and certification of the eradication of indigenous transmission of 2 of the 3 types of wild poliovirus (type 2 in 2015, after the last reported case in 1999, and type 3 in 2019, after the last reported case in 2012).

The herd immunity level will be denoted q. Recall that, for a stable state:

In turn,

![{\displaystyle R_{0}={\frac {N}{S}}={\frac {\mu N\operatorname {E} (T_{L})}{\mu N\operatorname {E} [\min(T_{L},T_{S})]}}={\frac {\operatorname {E} (T_{L})}{\operatorname {E} [\min(T_{L},T_{S})]}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bfedf01ca9b6742ed336fc18d22c1fe3025e83bd)

which is approximately:

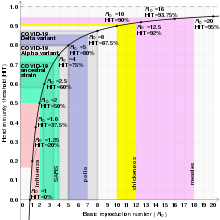

Graph of herd immunity threshold vs basic reproduction number with selected diseases

S will be (1 − q), since q is the proportion of the population that is immune and q + S must equal one (since in this simplified model, everyone is either susceptible or immune). Then:

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&R_{0}\cdot (1-q)=1,\\[6pt]&1-q={\frac {1}{R_{0}}},\\[6pt]&q=1-{\frac {1}{R_{0}}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c3e9c4b64bf2994d62ebaae1f24c481da90d3e47)

Remember that this is the threshold level. Die out of transmission will only occur if the proportion of immune individuals exceeds this level due to a mass vaccination programme.

We have just calculated the critical immunization threshold (denoted qc).

It is the minimum proportion of the population that must be immunized

at birth (or close to birth) in order for the infection to die out in

the population.

Because the fraction of the final size of the population p that is never infected can be defined as:

Hence,

Solving for  , we obtain:

, we obtain:

When mass vaccination cannot exceed the herd immunity

If the vaccine used is insufficiently effective or the required coverage cannot be reached, the program may fail to exceed qc. Such a program will protect vaccinated individuals from disease, but may change the dynamics of transmission.

Suppose that a proportion of the population q (where q < qc) is immunised at birth against an infection with R0 > 1. The vaccination programme changes R0 to Rq where

This change occurs simply because there are now fewer susceptibles in the population who can be infected. Rq is simply R0 minus those that would normally be infected but that cannot be now since they are immune.

As a consequence of this lower basic reproduction number, the average age of infection A will also change to some new value Aq in those who have been left unvaccinated.

Recall the relation that linked R0, A and L. Assuming that life expectancy has not changed, now:

But R0 = L/A so:

Thus, the vaccination program may raise the average age of infection, and unvaccinated individuals will experience a reduced force of infection

due to the presence of the vaccinated group. For a disease that leads

to greater clinical severity in older populations, the unvaccinated

proportion of the population may experience the disease relatively later

in life than would occur in the absence of vaccine.

When mass vaccination exceeds the herd immunity

If

a vaccination program causes the proportion of immune individuals in a

population to exceed the critical threshold for a significant length of

time, transmission of the infectious disease in that population will

stop. If elimination occurs everywhere at the same time, then this can

lead to eradication.

- Elimination

- Interruption of endemic transmission of an infectious disease, which

occurs if each infected individual infects less than one other, is

achieved by maintaining vaccination coverage to keep the proportion of

immune individuals above the critical immunization threshold.

- Eradication

- Elimination everywhere at the same time such that the infectious agent dies out (for example, smallpox and rinderpest).

Reliability

Models

have the advantage of examining multiple outcomes simultaneously,

rather than making a single forecast. Models have shown broad degrees of

reliability in past pandemics, such as SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Swine flu, MERS and Ebola.

![{\displaystyle R_{0}={\frac {N}{S}}={\frac {\mu N\operatorname {E} (T_{L})}{\mu N\operatorname {E} [\min(T_{L},T_{S})]}}={\frac {\operatorname {E} (T_{L})}{\operatorname {E} [\min(T_{L},T_{S})]}},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bfedf01ca9b6742ed336fc18d22c1fe3025e83bd)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&R_{0}\cdot (1-q)=1,\\[6pt]&1-q={\frac {1}{R_{0}}},\\[6pt]&q=1-{\frac {1}{R_{0}}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c3e9c4b64bf2994d62ebaae1f24c481da90d3e47)