From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Blitzkrieg ( BLITS-kreeg, German: [ˈblɪtskʁiːk] ( listen); from Blitz 'lightning' + Krieg 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air support,

that has the intent to break through the opponent's lines of defense,

then dislocate the defenders, unbalance the enemy by making it difficult

to respond to the continuously changing front, and defeat them in a

decisive Vernichtungsschlacht: a battle of annihilation.

listen); from Blitz 'lightning' + Krieg 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air support,

that has the intent to break through the opponent's lines of defense,

then dislocate the defenders, unbalance the enemy by making it difficult

to respond to the continuously changing front, and defeat them in a

decisive Vernichtungsschlacht: a battle of annihilation.

During the interwar period, aircraft and tank technologies matured and were combined with systematic application of the traditional German tactic of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare), deep penetrations and the bypassing of enemy strong points to encircle and destroy enemy forces in a Kesselschlacht (cauldron battle). During the Invasion of Poland, Western journalists adopted the term blitzkrieg to describe this form of armored warfare. The term had appeared in 1935, in a German military periodical Deutsche Wehr (German Defense), in connection to quick or lightning warfare. German maneuver operations were successful in the campaigns of 1939–1941 and by 1940 the term blitzkrieg was extensively used in Western media. Blitzkrieg operations capitalized on surprise penetrations (e.g., the penetration of the Ardennes forest region), general enemy unreadiness and their inability to match the pace of the German attack. During the Battle of France,

the French made attempts to reform defensive lines along rivers but

were frustrated when German forces arrived first and pressed on.

Despite being common in German and English-language journalism during World War II, the word Blitzkrieg was never used by the Wehrmacht as an official military term, except for propaganda. According to David Reynolds, "Hitler himself called the term Blitzkrieg 'A completely idiotic word' (ein ganz blödsinniges Wort)". Some senior officers, including Kurt Student, Franz Halder and Johann Adolf von Kielmansegg,

even disputed the idea that it was a military concept. Kielmansegg

asserted that what many regarded as blitzkrieg was nothing more than "ad

hoc solutions that simply popped out of the prevailing situation".

Student described it as ideas that "naturally emerged from the existing

circumstances" as a response to operational challenges. The Wehrmacht never officially adopted it as a concept or doctrine.

In 2005, the historian Karl-Heinz Frieser

summarized blitzkrieg as the result of German commanders using the

latest technology in the most advantageous way according to traditional

military principles and employing "the right units in the right place at

the right time".

Modern historians now understand blitzkrieg as the combination of the

traditional German military principles, methods and doctrines of the

19th century with the military technology of the interwar period.

Modern historians use the term casually as a generic description for

the style of maneuver warfare practiced by Germany during the early part

of World War II, rather than as an explanation. According to Frieser, in the context of the thinking of Heinz Guderian on mobile combined arms formations, blitzkrieg can be used as a synonym for modern maneuver warfare on the operational level.

Definition

Common interpretation

The traditional meaning of blitzkrieg is that of German tactical and operational

methodology in the first half of the Second World War, that is often

hailed as a new method of warfare. The word, meaning "lightning war" or

"lightning attack" in its strategic sense describes a series of quick

and decisive short battles to deliver a knockout blow to an enemy state

before it could fully mobilize. Tactically, blitzkrieg is a coordinated

military effort by tanks, motorized infantry, artillery and aircraft, to

create an overwhelming local superiority in combat power, to defeat the

opponent and break through its defenses. Blitzkrieg as used by Germany had considerable psychological, or "terror" elements, such as the Jericho Trompete, a noise-making siren on the Junkers Ju 87 dive-bomber, to affect the morale of enemy forces. The devices were largely removed when the enemy became used to the noise after the Battle of France in 1940 and instead bombs sometimes had whistles attached. It is also common for historians and writers to include psychological warfare by using Fifth columnists to spread rumors and lies among the civilian population in the theater of operations.

Origin of the term

The origin of the term blitzkrieg is obscure. It was never used in the title of a military doctrine or handbook of the German army or air force, and no "coherent doctrine" or "unifying concept of blitzkrieg" existed. The term seems rarely to have been used in the German military press before 1939 and recent research at the German Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt at Potsdam

found it in only two military articles from the 1930s. Both used the

term to mean a swift strategic knock-out, rather than a radical new

military doctrine or approach to war. The first article (1935) deals

primarily with supplies of food and materiel in wartime. The term blitzkrieg

is used with reference to German efforts to win a quick victory in the

First World War but is not associated with the use of armored,

mechanized or air forces. It argued that Germany must develop

self-sufficiency in food, because it might again prove impossible to

deal a swift knock-out to its enemies, leading to a long war.

In the second article (1938), launching a swift strategic knock-out is

described as an attractive idea for Germany but difficult to achieve on

land under modern conditions (especially against systems of fortification like the Maginot Line),

unless an exceptionally high degree of surprise could be achieved. The

author vaguely suggests that a massive strategic air attack might hold

out better prospects but the topic is not explored in detail. A third

relatively early use of the term in German occurs in Die Deutsche Kriegsstärke (German War Strength) by Fritz Sternberg, a Jewish, Marxist, political economist and refugee from Nazi Germany, published in 1938 in Paris and in London as Germany and a Lightning War. Sternberg wrote that Germany was not prepared economically for a long war but might win a quick war ("Blitzkrieg").

He did not go into detail about tactics or suggest that the German

armed forces had evolved a radically new operational method. His book

offers scant clues as to how German lightning victories might be won.

Ju 87 Bs over Poland, September–October 1939

In English and other languages, the term had been used since the 1920s. The term was first used in the publications of Ferdinand Otto Miksche, first in the magazine "Army Quarterly", and in his 1941 book, Blitzkrieg where he defined the concept. In September 1939, Time magazine termed the German military action as a "war of quick penetration and obliteration – Blitzkrieg, lightning war."

After the invasion of Poland, the British press commonly used the term

to describe German successes in that campaign, something Harris called

"a piece of journalistic sensationalism – a buzz-word with which to

label the spectacular early successes of the Germans in the Second World

War". It was later applied to the bombing of Britain, particularly

London, hence "The Blitz".

The German popular press followed suit nine months later, after the

fall of France in 1940; hence although the word had been used in German,

it was first popularized by British journalism. Heinz Guderian

referred to it as a word coined by the Allies: "as a result of the

successes of our rapid campaigns our enemies ... coined the word Blitzkrieg".

After the German failure in the Soviet Union in 1941, use of the term

began to be frowned upon in Nazi Germany, and Hitler then denied ever

using the term, saying in a speech in November 1941, "I have never used

the word Blitzkrieg, because it is a very silly word". In early January 1942, Hitler dismissed it as "Italian phraseology".

Military evolution, 1919–1939

Germany

In 1914, German strategic thinking derived from the writings of Carl von Clausewitz (1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831), Helmuth von Moltke the Elder (26 October 1800 – 24 April 1891) and Alfred von Schlieffen

(28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913), who advocated maneuver, mass and

envelopment to create the conditions for a decisive battle (Vernichtungsschlacht). During the war, officers such as Willy Rohr developed tactics to restore maneuver on the battlefield. Specialist light infantry (Stosstruppen,

"storm troops") were to exploit weak spots to make gaps for larger

infantry units to advance with heavier weapons and exploit the success,

leaving isolated strong points to troops following up. Infiltration

tactics were combined with short hurricane artillery bombardments using massed artillery, devised by Colonel Georg Bruchmüller. Attacks relied on speed and surprise rather than on weight of numbers. These tactics met with great success in Operation Michael, the German spring offensive

of 1918 and restored temporarily the war of movement, once the Allied

trench system had been overrun. The German armies pushed on towards

Amiens and then Paris, coming within 120 kilometres (75 mi) before

supply deficiencies and Allied reinforcements halted the advance.

Historian James Corum criticized the German leadership for

failing to understand the technical advances of the First World War,

having conducted no studies of the machine gun prior to the war, and giving tank production the lowest priority during the war. Following Germany's defeat, the Treaty of Versailles limited the Reichswehr to a maximum of 100,000 men, making impossible the deployment of mass armies. The German General Staff was abolished by the treaty but continued covertly as the Truppenamt (Troop Office), disguised as an administrative body. Committees of veteran staff officers were formed within the Truppenamt to evaluate 57 issues of the war to revise German operational theories. By the time of the Second World War, their reports had led to doctrinal and training publications, including H. Dv. 487, Führung und Gefecht der verbundenen Waffen (Command and Battle of the Combined Arms), known as das Fug (1921–23) and Truppenführung (1933–34), containing standard procedures for combined-arms warfare. The Reichswehr

was influenced by its analysis of pre-war German military thought, in

particular infiltration tactics, which at the end of the war had seen

some breakthroughs on the Western Front and the maneuver warfare which

dominated the Eastern Front.

On the Eastern Front, the war did not bog down into trench warfare;

German and Russian armies fought a war of maneuver over thousands of

miles, which gave the German leadership unique experience not available

to the trench-bound western Allies.

Studies of operations in the east led to the conclusion that small and

coordinated forces possessed more combat power than large, uncoordinated

forces. After the war, the Reichswehr expanded and improved infiltration tactics. The commander in chief, Hans von Seeckt, argued that there had been an excessive focus on encirclement and emphasized speed instead. Seeckt inspired a revision of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare) thinking and its associated Auftragstaktik,

in which the commander expressed his goals to subordinates and gave

them discretion in how to achieve them; the governing principle was "the

higher the authority, the more general the orders were", so it was the

responsibility of the lower echelons to fill in the details. Implementation of higher orders remained within limits determined by the training doctrine of an elite officer-corps.

Delegation of authority to local commanders increased the tempo of

operations, which had great influence on the success of German armies in

the early war period. Seeckt, who believed in the Prussian tradition of

mobility, developed the German army into a mobile force, advocating

technical advances that would lead to a qualitative improvement of its

forces and better coordination between motorized infantry, tanks, and

planes.

Britain

The British Army took lessons from the successful infantry and

artillery offensives on the Western Front in late 1918. To obtain the

best co-operation between all arms, emphasis was placed on detailed

planning, rigid control and adherence to orders. Mechanization of the

army was considered a means to avoid mass casualties and indecisive

nature of offensives, as part of a combined-arms theory of war. The four editions of Field Service Regulations

published after 1918 held that only combined-arms operations could

create enough fire power to enable mobility on a battlefield. This

theory of war also emphasized consolidation, recommending caution

against overconfidence and ruthless exploitation.

In the Sinai and Palestine campaign, operations involved some aspects of what would later be called blitzkrieg. The decisive Battle of Megiddo

included concentration, surprise and speed; success depended on

attacking only in terrain favoring the movement of large formations

around the battlefield and tactical improvements in the British

artillery and infantry attack. General Edmund Allenby used infantry to attack the strong Ottoman front line in co-operation with supporting artillery, augmented by the guns of two destroyers. Through constant pressure by infantry and cavalry, two Ottoman armies in the Judean Hills were kept off-balance and virtually encircled during the Battles of Sharon and Nablus (Battle of Megiddo).

The British methods induced "strategic paralysis" among the Ottomans and led to their rapid and complete collapse. In an advance of 65 miles (105 km), captures were estimated to be "at least 25,000 prisoners and 260 guns."

Liddell Hart considered that important aspects of the operation were

the extent to which Ottoman commanders were denied intelligence on the

British preparations for the attack through British air superiority and

air attacks on their headquarters and telephone exchanges, which

paralyzed attempts to react to the rapidly deteriorating situation.

France

Norman Stone detects early blitzkrieg operations in offensives by the French generals Charles Mangin and Marie-Eugène Debeney in 1918. However, French doctrine in the interwar years became defense-oriented. Colonel Charles de Gaulle advocated concentration of armor and airplanes. His opinions appeared in his book Vers l'Armée de métier

(Towards the Professional Army, 1933). Like von Seeckt, de Gaulle

concluded that France could no longer maintain the huge armies of

conscripts and reservists which had fought World War I, and he sought to

use tanks, mechanized forces and aircraft to allow a smaller number of

highly trained soldiers to have greater impact in battle. His views

little endeared him to the French high command, but are claimed by some to have influenced Heinz Guderian.

Russia/USSR

In 1916 General Alexei Brusilov had used surprise and infiltration tactics during the Brusilov Offensive. Later, Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893-1937), Georgii Isserson [ru] (1898-1976) and other members of the Red Army developed a concept of deep battle from the experience of the Polish–Soviet War

of 1919–1920. These concepts would guide Red Army doctrine throughout

World War II. Realizing the limitations of infantry and cavalry,

Tukhachevsky advocated mechanized formations and the large-scale

industrialization they required. Robert Watt (2008) wrote that

blitzkrieg has little in common with Soviet deep battle.

In 2002 H. P. Willmott had noted that deep battle contained two

important differences: it was a doctrine of total war (not of limited

operations), and rejected decisive battle in favor of several large,

simultaneous offensives.

The Reichswehr and the Red Army began a secret collaboration in the Soviet Union to evade the Treaty of Versailles occupational agent, the Inter-Allied Commission. In 1926 war-games and tests began at Kazan and Lipetsk in the RSFSR.

The centers served to field-test aircraft and armored vehicles up to

the battalion level and housed aerial- and armoured-warfare schools,

through which officers rotated.

Nazi Germany

After becoming Chancellor of Germany (head of government) in 1933, Adolf Hitler

ignored the Versailles Treaty provisions. Within the Wehrmacht

(established in 1935) the command for motorized armored forces was named

the Panzerwaffe in 1936. The Luftwaffe

(the German air force) was officially established in February 1935, and

development began on ground-attack aircraft and doctrines. Hitler

strongly supported this new strategy. He read Guderian's 1937 book Achtung – Panzer! and upon observing armored field exercises at Kummersdorf he remarked, "That is what I want – and that is what I will have."

Guderian

Guderian summarized combined-arms tactics as the way to get the

mobile and motorized armored divisions to work together and support each

other to achieve decisive success. In his 1950 book, Panzer Leader, he wrote:

In this year, 1929, I became

convinced that tanks working on their own or in conjunction with

infantry could never achieve decisive importance. My historical studies,

the exercises carried out in England and our own experience with

mock-ups had persuaded me that the tanks would never be able to produce

their full effect until the other weapons on whose support they must

inevitably rely were brought up to their standard of speed and of

cross-country performance. In such formation of all arms, the tanks must

play primary role, the other weapons being subordinated to the

requirements of the armor. It would be wrong to include tanks in

infantry divisions; what was needed were armored divisions which would

include all the supporting arms needed to allow the tanks to fight with

full effect.

Guderian believed that developments in technology were required to

support the theory; especially, equipping armored divisions—tanks

foremost–with wireless communications. Guderian insisted in 1933 to the

high command that every tank in the German armored force must be

equipped with a radio.

At the start of World War II, only the German army was thus prepared

with all tanks "radio-equipped". This proved critical in early tank

battles where German tank commanders exploited the organizational

advantage over the Allies

that radio communication gave them. Later all Allied armies would copy

this innovation. During the Polish campaign, the performance of armored

troops, under the influence of Guderian's ideas, won over a number of

skeptics who had initially expressed doubt about armored warfare, such

as von Rundstedt and Rommel.

Rommel

According to David A.Grossman, by the 12th Battle of Isonzo

(October–November 1917), while conducting a light-infantry operation,

Rommel had perfected his maneuver-warfare principles, which were the

very same ones that were applied during the Blitzkrieg against France in

1940 (and repeated in the Coalition ground offensive against Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War).

During the Battle of France and against his staff advisor's advice,

Hitler ordered that everything should be completed in a few weeks;

fortunately for the Führer, Rommel and Guderian disobeyed the General

Staff's orders (particularly General von Kleist) and forged ahead making quicker progress than anyone expected, and on the way, "inventing the idea of Blitzkrieg". It was Rommel who created the new archetype of Blitzkrieg, leading his division far ahead of flanking divisions.

MacGregor and Williamson remark that Rommel's version of Blitzkrieg

displayed a significantly better understanding of combined-arms warfare

than that of Guderian. General Hoth

submitted an official report in July 1940 which declared that Rommel

had "explored new paths in the command of Panzer divisions".

Methods of operations

Schwerpunkt

Schwerpunktprinzip was a heuristic

device (conceptual tool or thinking formula) used in the German army

since the nineteenth century, to make decisions from tactics to strategy

about priority. Schwerpunkt has been translated as center of gravity, crucial, focal point and point of main effort. None of these forms is sufficient to describe the universal importance of the term and the concept of Schwerpunktprinzip. Every unit in the army, from the company to the supreme command, decided on a Schwerpunkt through schwerpunktbildung,

as did the support services, which meant that commanders always knew

what was most important and why. The German army was trained to support

the Schwerpunkt, even when risks had to be taken elsewhere to

support the point of main effort as well as attacking with overwhelming

firepower. Through Schwerpunktbildung, the German army could achieve superiority at the Schwerpunkt, whether attacking or defending, to turn local success at the Schwerpunkt

into the progressive disorganisation of the opposing force, creating

more opportunities to exploit this advantage, even if numerically and strategically inferior in general. In the 1930s, Guderian summarized this as "Klotzen, nicht kleckern!" ("Kick, don't spatter them!").

Pursuit

Having achieved a breakthrough of the enemy's line, units comprising the Schwerpunkt

were not supposed to become decisively engaged with enemy front line

units to the right and left of the breakthrough area. Units pouring

through the hole were to drive upon set objectives behind the enemy

front line. In World War II, German Panzer forces used motorized

mobility to paralyze the opponent's ability to react. Fast-moving mobile

forces seized the initiative, exploited weaknesses and acted before

opposing forces could respond. Central to this was the decision cycle

(tempo). Through superior mobility and faster decision-making cycles,

mobile forces could act quicker than the forces opposing them. Directive control was a fast and flexible method of command. Rather than receiving an explicit order, a commander would be told of his superior's intent

and the role which his unit was to fill in this concept. The method of

execution was then a matter for the discretion of the subordinate

commander. Staff burden was reduced at the top and spread among tiers of

command with knowledge about their situation. Delegation and the

encouragement of initiative aided implementation, important decisions

could be taken quickly and communicated verbally or with brief written

orders.

Mopping-up

The last part of an offensive operation was the destruction of un-subdued pockets of resistance, which had been enveloped earlier and by-passed by the fast-moving armored and motorized spearheads. The Kesselschlacht 'cauldron battle' was a concentric

attack on such pockets. It was here that most losses were inflicted

upon the enemy, primarily through the mass capture of prisoners and

weapons. During Operation Barbarossa, huge encirclements in 1941 produced nearly 3.5 million Soviet prisoners, along with masses of equipment.

Air power

Close air support was provided in the form of the dive bomber and medium bomber.

They would support the focal point of attack from the air. German

successes are closely related to the extent to which the German Luftwaffe was able to control the air war in early campaigns in Western and Central Europe, and the Soviet Union. However, the Luftwaffe

was a broadly based force with no constricting central doctrine, other

than its resources should be used generally to support national

strategy. It was flexible and it was able to carry out both

operational-tactical, and strategic bombing. Flexibility was the Luftwaffe's

strength in 1939–1941. Paradoxically, from that period onward it became

its weakness. While Allied Air Forces were tied to the support of the

Army, the Luftwaffe deployed its resources in a more general, operational way. It switched from air superiority

missions, to medium-range interdiction, to strategic strikes, to close

support duties depending on the need of the ground forces. In fact, far

from it being a specialist panzer spearhead arm, less than 15 percent of

the Luftwaffe was intended for close support of the army in 1939.

Stimulants

Amphetamine

use is believed to have played a role in the speed of Germany's initial

Blitzkrieg, since military success employing combined arms demanded

long hours of continuous operations with minimal rest.

Limitations and countermeasures

Environment

The concepts associated with the term blitzkrieg—deep

penetrations by armor, large encirclements, and combined arms

attacks—were largely dependent upon terrain and weather conditions.

Where the ability for rapid movement across "tank country" was not

possible, armored penetrations often were avoided or resulted in

failure. Terrain would ideally be flat, firm, unobstructed by natural

barriers or fortifications, and interspersed with roads and railways. If

it were instead hilly, wooded, marshy, or urban, armor would be

vulnerable to infantry in close-quarters combat and unable to break out

at full speed. Additionally, units could be halted by mud (thawing

along the Eastern Front regularly slowed both sides) or extreme snow.

Operation Barbarossa helped confirm that armor effectiveness and the

requisite aerial support were dependent on weather and terrain.

It should however be noted that the disadvantages of terrain could be

nullified if surprise was achieved over the enemy by an attack through

areas considered natural obstacles, as occurred during the Battle of

France when the German blitzkrieg-style attack went through the

Ardennes.

Since the French thought the Ardennes unsuitable for massive troop

movement, particularly for tanks, they were left with only light

defenses which were quickly overrun by the Wehrmacht. The Germans quickly advanced through the forest, knocking down the trees the French thought would impede this tactic.

Air superiority

The influence of air forces over forces on the ground changed

significantly over the course of the Second World War. Early German

successes were conducted when Allied aircraft could not make a

significant impact on the battlefield. In May 1940, there was near

parity in numbers of aircraft between the Luftwaffe and the Allies, but the Luftwaffe

had been developed to support Germany's ground forces, had liaison

officers with the mobile formations, and operated a higher number of

sorties per aircraft.

In addition, German air parity or superiority allowed the unencumbered

movement of ground forces, their unhindered assembly into concentrated

attack formations, aerial reconnaissance, aerial resupply of fast moving

formations and close air support at the point of attack. The Allied air forces had no close air support aircraft, training or doctrine.

The Allies flew 434 French and 160 British sorties a day but methods of

attacking ground targets had yet to be developed; therefore Allied

aircraft caused negligible damage. Against these 600 sorties the Luftwaffe on average flew 1,500 sorties a day. On 13 May, Fliegerkorps

VIII flew 1,000 sorties in support of the crossing of the Meuse. The

following day the Allies made repeated attempts to destroy the German

pontoon bridges, but German fighter aircraft, ground fire and Luftwaffe flak batteries with the panzer forces destroyed 56 percent of the attacking Allied aircraft while the bridges remained intact.

Allied air superiority became a significant hindrance to German

operations during the later years of the war. By June 1944 the Western

Allies had complete control of the air over the battlefield and their

fighter-bomber aircraft were very effective at attacking ground forces.

On D-Day the Allies flew 14,500 sorties over the battlefield area alone,

not including sorties flown over north-western Europe. Against this on 6

June the Luftwaffe flew some 300 sorties. Though German fighter

presence over Normandy increased over the next days and weeks, it never

approached the numbers the Allies commanded. Fighter-bomber attacks on

German formations made movement during daylight almost impossible.

Subsequently, shortages soon developed in food, fuel and ammunition,

severely hampering the German defenders. German vehicle crews and even

flak units experienced great difficulty moving during daylight. Indeed, the final German offensive operation in the west, Operation Wacht am Rhein,

was planned to take place during poor weather to minimize interference

by Allied aircraft. Under these conditions it was difficult for German

commanders to employ the "armored idea", if at all.

Counter-tactics

Blitzkrieg is vulnerable to an enemy that is robust enough to weather

the shock of the attack and that does not panic at the idea of enemy

formations in its rear area. This is especially true if the attacking

formation lacks the reserve to keep funnelling forces into the

spearhead, or lacks the mobility to provide infantry, artillery and

supplies into the attack. If the defender can hold the shoulders of the

breach they will have the opportunity to counter-attack into the flank

of the attacker, potentially cutting off the van as happened to Kampfgruppe Peiper in the Ardennes.

During the Battle of France in 1940, the 4th Armoured Division (Major-General Charles de Gaulle) and elements of the 1st Army Tank Brigade (British Expeditionary Force)

made probing attacks on the German flank, pushing into the rear of the

advancing armored columns at times. This may have been a reason for

Hitler to call a halt to the German advance. Those attacks combined with

Maxime Weygand's Hedgehog tactic would become the major basis for responding to blitzkrieg attacks in the future: deployment in depth,

permitting enemy or "shoulders" of a penetration was essential to

channelling the enemy attack, and artillery, properly employed at the

shoulders, could take a heavy toll of attackers. While Allied forces in

1940 lacked the experience to successfully develop these strategies,

resulting in France's capitulation with heavy losses, they characterized

later Allied operations. At the Battle of Kursk

the Red Army employed a combination of defense in great depth,

extensive minefields, and tenacious defense of breakthrough shoulders.

In this way they depleted German combat power even as German forces

advanced. The reverse can be seen in the Russian summer offensive of 1944, Operation Bagration,

which resulted in the destruction of Army Group Center. German attempts

to weather the storm and fight out of encirclements failed due to the

Russian ability to continue to feed armored units into the attack,

maintaining the mobility and strength of the offensive, arriving in

force deep in the rear areas, faster than the Germans could regroup.

Logistics

Although

effective in quick campaigns against Poland and France, mobile

operations could not be sustained by Germany in later years. Strategies

based on maneuver have the inherent danger of the attacking force

overextending its supply lines,

and can be defeated by a determined foe who is willing and able to

sacrifice territory for time in which to regroup and rearm, as the

Soviets did on the Eastern Front (as opposed to, for example, the Dutch

who had no territory to sacrifice). Tank and vehicle production was a

constant problem for Germany; indeed, late in the war many panzer

"divisions" had no more than a few dozen tanks. As the end of the war approached, Germany also experienced critical shortages in fuel and ammunition stocks as a result of Anglo-American strategic bombing and blockade. Although production of Luftwaffe

fighter aircraft continued, they would be unable to fly for lack of

fuel. What fuel there was went to panzer divisions, and even then they

were not able to operate normally. Of those Tiger tanks lost against the United States Army, nearly half of them were abandoned for lack of fuel.

Military operations

Spanish Civil War

German volunteers first used armor in live field-conditions during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. Armor commitment consisted of Panzer Battalion 88, a force built around three companies of Panzer I tanks that functioned as a training cadre for Spain's Nationalists. The Luftwaffe deployed squadrons of fighters, dive-bombers and transport aircraft as the Condor Legion. Guderian said that the tank deployment was "on too small a scale to allow accurate assessments to be made". (The true test of his "armored idea" would have to wait for the Second World War.) However, the Luftwaffe also provided volunteers to Spain to test both tactics and aircraft in combat, including the first combat use of the Stuka.

During the war, the Condor Legion undertook the 1937 bombing of Guernica, which had a tremendous psychological effect on the populations of Europe. The results were exaggerated, and the Western Allies

concluded that the "city-busting" techniques were now a part of the

German way in war. The targets of the German aircraft were actually the

rail lines and bridges. But lacking the ability to hit them with

accuracy (only three or four Ju 87s saw action in Spain), the Luftwaffe chose a method of carpet bombing, resulting in heavy civilian casualties.

Poland, 1939

In

Poland, fast-moving armies encircled Polish forces (blue circles), but

not by independent armored operations. Combined tank, artillery,

infantry and air forces were used.

Although journalists popularized the term blitzkrieg during

the September 1939 invasion of Poland, historians Matthew Cooper and J.

P. Harris have written that German operations during this campaign were

consistent with traditional methods. The Wehrmacht strategy was more in

line with Vernichtungsgedanke

- a focus on envelopment to create pockets in broad-front annihilation.

The German generals dispersed Panzer forces among the three German

concentrations with little emphasis on independent use; they deployed

tanks to create or destroy close pockets of Polish forces and to seize operational-depth terrain in support of the largely un-motorized infantry which followed.

While the Wehrmacht used available models of tanks, Stuka

dive-bombers and concentrated forces in the Polish campaign, the

majority of the fighting involved conventional infantry and artillery

warfare, and most Luftwaffe action was independent of the ground

campaign. Matthew Cooper wrote that

[t]hroughout the Polish Campaign,

the employment of the mechanised units revealed the idea that they were

intended solely to ease the advance and to support the activities of the

infantry... Thus, any strategic exploitation of the armoured idea was

still-born. The paralysis of command and the breakdown of morale were

not made the ultimate aim of the ... German ground and air forces, and

were only incidental by-products of the traditional maneuvers of rapid

encirclement and of the supporting activities of the flying artillery of

the Luftwaffe, both of which had as their purpose the physical

destruction of the enemy troops. Such was the Vernichtungsgedanke of the Polish campaign.

John Ellis wrote that "…there is considerable justice in Matthew

Cooper's assertion that the panzer divisions were not given the kind of strategic

mission that was to characterize authentic armored blitzkrieg, and were

almost always closely subordinated to the various mass infantry

armies". Steven Zaloga

wrote, "Whilst Western accounts of the September campaign have stressed

the shock value of the panzer and Stuka attacks, they have tended to

underestimate the punishing effect of German artillery on Polish units.

Mobile and available in significant quantity, artillery shattered as

many units as any other branch of the Wehrmacht."

Low Countries and France, 1940

German advances during the Battle of Belgium

The German invasion of France, with subsidiary attacks on Belgium and

the Netherlands, consisted of two phases, Operation Yellow (Fall Gelb) and Operation Red (Fall Rot). Yellow opened with a feint conducted against the Netherlands and Belgium by two armored corps and paratroopers. Most of the German armored forces were placed in Panzer Group Kleist, which attacked through the Ardennes,

a lightly-defended sector that the French planned to reinforce if need

be, before the Germans could bring up heavy and siege artillery.

There was no time for the French to send such reinforcement, for the

Germans did not wait for siege artillery but reached the Meuse and

achieved a breakthrough at the Battle of Sedan in three days.

Panzer Group Kleist raced to the English Channel, reaching the coast at Abbeville, and cut off the BEF, the Belgian Army and some of the best-equipped divisions of the French Army

in northern France. Armored and motorized units under Guderian, Rommel

and others, advanced far beyond the marching and horse-drawn infantry

divisions and far in excess of what Hitler and the German high command

expected or wished. When the Allies counter-attacked at Arras using the heavily-armored British Matilda I and Matilda II tanks, a brief panic ensued in the German High Command. Hitler halted his armored and motorized forces outside the port of Dunkirk, which the Royal Navy had started using to evacuate the Allied forces. Hermann Göring

promised that the Luftwaffe would complete the destruction of the

encircled armies, but aerial operations failed to prevent the evacuation

of the majority of the Allied troops. In Operation Dynamo some 330,000 French and British troops escaped.

Case Yellow surprised everyone, overcoming the Allies' 4,000

armored vehicles, many of which were better than their German

equivalents in armor and gun-power.

The French and British frequently used their tanks in the dispersed

role of infantry support rather than concentrating force at the point of

attack, to create overwhelming firepower.

German advances during the Battle of France

The French armies were much reduced in strength and the confidence of

their commanders shaken. With much of their own armor and heavy

equipment lost in Northern France, they lacked the means to fight a

mobile war. The Germans followed their initial success with Operation

Red, a triple-pronged offensive. The XV Panzer Corps attacked towards Brest, XIV Panzer Corps attacked east of Paris, towards Lyon

and the XIX Panzer Corps encircled the Maginot Line. The French, hard

pressed to organize any sort of counter-attack, were continually ordered

to form new defensive lines and found that German forces had already

by-passed them and moved on. An armored counter-attack organized by

Colonel de Gaulle could not be sustained, and he had to retreat.

Prior to the German offensive in May, Winston Churchill had said "Thank God for the French Army".

That same French army collapsed after barely two months of fighting.

This was in shocking contrast to the four years of trench warfare which

French forces had engaged in during the First World War. The French

president of the Ministerial Council, Reynaud, analyzed the collapse in a

speech on 21 May 1940:

The truth is that our classic

conception of the conduct of war has come up against a new conception.

At the basis of this...there is not only the massive use of heavy

armoured divisions or cooperation between them and airplanes, but the

creation of disorder in the enemy's rear by means of parachute raids.

The Germans had not used paratroop attacks in France and only made

one big drop in the Netherlands, to capture three bridges; some small

glider-landings were conducted in Belgium to take bottle-necks on routes

of advance before the arrival of the main force (the most renowned

being the landing on Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium).

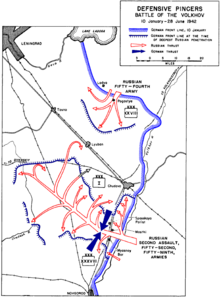

Eastern Front, 1941–44

After

1941–42, the Wehrmacht increasingly used armoured formations as a

mobile reserve against Allied breakthroughs. The blue arrows depict

armoured counter-attacks.

Use of armored forces was crucial for both sides on the Eastern Front. Operation Barbarossa,

the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, involved a number

of breakthroughs and encirclements by motorized forces. Its goal -

according to Führer Directive 21

(18 December 1940) - was "to destroy the Russian forces deployed in the

West and to prevent their escape into the wide-open spaces of Russia". The Red Army was to be destroyed west of the Dvina and Dnieper

rivers, which were about 500 kilometres (310 mi) east of the Soviet

border, to be followed by a mopping-up operation. The surprise attack

resulted in the near annihilation of the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS, Soviet Air Force) by simultaneous attacks on airfields, allowing the Luftwaffe to achieve total air supremacy over all the battlefields within the first week.

On the ground, four German panzer groups outflanked and encircled

disorganized Red Army units, while the marching infantry completed the

encirclements and defeated the trapped forces. In late July, after 2nd Panzer Group

(commanded by Guderian) captured the watersheds of the Dvina and

Dnieper rivers near Smolensk, the panzers had to defend the

encirclement, because the marching infantry divisions remained hundreds

of kilometers to the west.

The Germans conquered large areas of the Soviet Union, but their

failure to destroy the Red Army before the winter of 1941-1942 was a

strategic failure that made German tactical superiority and territorial

gains irrelevant. The Red Army had survived enormous losses and regrouped with new formations far to the rear of the front line. During the Battle of Moscow (October 1941 to January 1942), the Red Army defeated the German Army Group Center and for the first time in the war seized the strategic initiative.

In the summer of 1942, Germany launched another offensive, this time focusing on Stalingrad and the Caucasus in the southern USSR.

The Soviets again lost tremendous amounts of territory, only to

counter-attack once more during winter. German gains were ultimately

limited because Hitler diverted forces from the attack on Stalingrad and drove towards the Caucasus oilfields simultaneously. The Wehrmacht

became overstretched: although winning operationally, it could not

inflict a decisive defeat as the durability of the Soviet Union's

manpower, resources, industrial base and aid from the Western Allies

began to take effect.

In July 1943 the Wehrmacht conducted Operation Zitadelle (Citadel) against a salient at Kursk which Soviet troop heavily defended. Soviet defensive tactics had by now hugely improved, particularly in the use of artillery and air support. By April 1943, the Stavka had learned of German intentions through intelligence supplied by front-line reconnaissance and Ultra intercepts. In the following months, the Red Army constructed deep defensive belts along the paths of the planned German attack.

The Soviets made a concerted effort to disguise their knowledge of

German plans and the extent of their own defensive preparations, and the

German commanders still hoped to achieve operational surprise when the

attack commenced.

The Germans did not achieve surprise and were not able to outflank or break through into enemy rear-areas during the operation. Several historians assert that Operation Citadel was planned and intended to be a blitzkrieg operation. Many of the German participants who wrote about the operation after the war, including Manstein, make no mention of blitzkrieg in their accounts.

In 2000, Niklas Zetterling and Anders Frankson characterized only the

southern pincer of the German offensive as a "classical blitzkrieg

attack".

Pier Battistelli wrote that the operational planning marked a change in

German offensive thinking away from blitzkrieg and that more priority

was given to brute force and fire power than to speed and maneuver.

In 1995, David Glantz

stated that for the first time, blitzkrieg was defeated in summer and

the opposing Soviet forces were able to mount a successful

counter-offensive. The Battle of Kursk ended with two Soviet counter-offensives and the revival of deep operations. In the summer of 1944, the Red Army destroyed Army Group Centre in Operation Bagration,

using combined-arms tactics for armor, infantry and air power in a

coordinated strategic assault, known as deep operations, which led to an

advance of 600 kilometres (370 mi) in six weeks.

Western Front, 1944–45

Allied

armies began using combined-arms formations and deep-penetration

strategies that Germany had used in the opening years of the war. Many

Allied operations in the Western Desert

and on the Eastern Front, relied on firepower to establish

breakthroughs by fast-moving armored units. These artillery-based

tactics were also decisive in Western Front operations after 1944's Operation Overlord,

and the British Commonwealth and American armies developed flexible and

powerful systems for using artillery support. What the Soviets lacked

in flexibility, they made up for in number of rocket launchers, guns and mortars. The Germans never achieved the kind of fire concentrations their enemies were capable of by 1944.

After the Allied landings in Normandy

(June 1944), the Germans began a counter-offensive to overwhelm the

landing force with armored attacks - but these failed due to a lack of

co-ordination and to Allied superiority in anti-tank defense and in the

air. The most notable attempt to use deep-penetration operations in

Normandy was Operation Luttich at Mortain, which only hastened the Falaise Pocket

and the destruction of German forces in Normandy. The Mortain

counter-attack was defeated by the US 12th Army Group with little effect

on its own offensive operations.

The last German offensive on the Western front, the Battle of the Bulge (Operation Wacht am Rhein), was an offensive launched towards the port of Antwerp

in December 1944. Launched in poor weather against a thinly-held Allied

sector, it achieved surprise and initial success as Allied air-power

was grounded due to cloud cover. Determined defense by US troops in

places throughout the Ardennes, the lack of good roads and German supply

shortages caused delays. Allied forces deployed to the flanks of the

German penetration and as soon as the skies cleared, Allied aircraft

returned to the battlefield. Allied counter-attacks soon forced back the

Germans, who abandoned much equipment for lack of fuel.

Post-war controversy

Blitzkrieg had been called a Revolution in Military Affairs

(RMA) but many writers and historians have concluded that the Germans

did not invent a new form of warfare but applied new technologies to

traditional ideas of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare) to achieve decisive victory.

Strategy

In 1965, Captain Robert O'Neill, Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford produced an example of the popular view. In Doctrine and Training in the German Army 1919–1939, O'Neill wrote

What makes this story worth telling

is the development of one idea: the blitzkrieg. The German Army had a

greater grasp of the effects of technology on the battlefield, and went

on to develop a new form of warfare by which its rivals when it came to

the test were hopelessly outclassed.

Other historians wrote that blitzkrieg was an operational doctrine of

the German armed forces and a strategic concept on which the leadership

of Nazi Germany based its strategic and economic planning. Military

planners and bureaucrats in the war economy appear rarely, if ever, to

have employed the term blitzkrieg in official documents. That the

German army had a "blitzkrieg doctrine" was rejected in the late 1970s

by Matthew Cooper. The concept of a blitzkrieg Luftwaffe was challenged by Richard Overy

in the late 1970s and by Williamson Murray in the mid-1980s. That Nazi

Germany went to war on the basis of "blitzkrieg economics" was

criticized by Richard Overy in the 1980s and George Raudzens described

the contradictory senses in which historians have used the word. The

notion of a German blitzkrieg concept or doctrine survives in popular

history and many historians still support the thesis.

Frieser wrote that after the failure of the Schlieffen Plan

in 1914, the German army concluded that decisive battles were no longer

possible in the changed conditions of the twentieth century. Frieser

wrote that the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

(OKW), which was created in 1938 had intended to avoid the decisive

battle concepts of its predecessors and planned for a long war of

exhaustion (ermattungskrieg). It was only after the improvised

plan for the Battle of France in 1940 was unexpectedly successful, that

the German General Staff came to believe that vernichtungskrieg was still feasible. German thinking reverted to the possibility of a quick and decisive war for the Balkan campaign and Operation Barbarossa.

Doctrine

Most academic historians regard the notion of blitzkrieg as military doctrine to be a myth. Shimon Naveh

wrote "The striking feature of the blitzkrieg concept is the complete

absence of a coherent theory which should have served as the general

cognitive basis for the actual conduct of operations". Naveh described

it as an "ad hoc solution" to operational dangers, thrown together at

the last moment.

Overy disagreed with the idea that Hitler and the Nazi regime ever

intended a blitzkrieg war, because the once popular belief that the Nazi

state organized their economy to carry out its grand strategy in short

campaigns was false. Hitler had intended for a rapid unlimited war to

occur much later than 1939, but Germany's aggressive foreign policy forced the Nazi state into war before it was ready. Hitler and the Wehrmacht's planning in the 1930s did not reflect a blitzkrieg method but the opposite.

John Harris wrote that the Wehrmacht never used the word, and it did

not appear in German army or air force field manuals; the word was

coined in September 1939, by a Times newspaper reporter. Harris also found no evidence that German military thinking developed a blitzkrieg mentality. Karl-Heinz Frieser and Adam Tooze reached similar conclusions to Overy and Naveh, that the notions of blitzkrieg-economy and strategy were myths.

Frieser wrote that surviving German economists and General Staff

officers denied that Germany went to war with a blitzkrieg strategy. Robert M. Citino argues:

Blitzkrieg was not a doctrine, or an operational scheme, or

even a tactical system. In fact, it simply doesn’t exist, at least not

in the way we usually think it does. The Germans never used the term Blitzkrieg

in any precise sense, and almost never used it outside of quotations.

It simply meant a rapid and decisive victory (lightning war)... The

Germans didn’t invent anything new in the interwar period, but rather

used new technologies like tanks and air and radio-controlled command to

restore an old way of war that they still found to be valid, Bewegungskrieg.

Historian Victor Davis Hanson states that Blitzkrieg "played

on the myth of German technological superiority and industrial

dominance," adding that German successes, particularly that of its

Panzer divisions were "instead predicated on the poor preparation and

morale of Germany's enemies." Hanson also reports that at a Munich public address in November 1941, Hitler had "disowned" the concept of Blitzkrieg by calling it an "idiotic word." Further, successful Blitzkrieg

operations were predicated on superior numbers, air-support, and were

only possible for short periods of time without sufficient supply lines. For all intents and purposes, Blitzkrieg

ended at the Eastern Front once the German forces gave up Stalingrad,

after they faced hundreds of new T-34 tanks, when the Luftwaffe became

unable to assure air dominance, and following the stalemate at Kursk—to

this end, Hanson concludes that German military success was not

accompanied by the adequate provisioning of its troops with food and

materiel far from the source of supply, which contributed to its

ultimate failures. Despite its later disappointments as German troops extended their lines at too great a distance, the very specter of armored Blitzkrieg forces initially proved victorious against Polish, Dutch, Belgian, and French armies early in the war.

Economics

In

the 1960s, Alan Milward developed a theory of blitzkrieg economics, that

Germany could not fight a long war and chose to avoid comprehensive

rearmament and armed in breadth, to win quick victories. Milward

described an economy positioned between a full war economy and a

peacetime economy.

The purpose of the blitzkrieg economy was to allow the German people to

enjoy high living standards in the event of hostilities and avoid the

economic hardships of the First World War.

Overy wrote that blitzkrieg as a "coherent military and economic

concept has proven a difficult strategy to defend in light of the

evidence".

Milward's theory was contrary to Hitler's and German planners'

intentions. The Germans, aware of the errors of the First World War,

rejected the concept of organizing its economy to fight only a short

war. Therefore, focus was given to the development of armament in depth

for a long war, instead of armament in breadth for a short war. Hitler

claimed that relying on surprise alone was "criminal" and that "we have

to prepare for a long war along with surprise attack". During the winter

of 1939–40, Hitler demobilized many troops from the army to return as

skilled workers to factories because the war would be decided by

production, not a quick "Panzer operation".

In the 1930s, Hitler had ordered rearmament programs that cannot

be considered limited. In November 1937 Hitler had indicated that most

of the armament projects would be completed by 1943–45. The rearmament of the Kriegsmarine was to have been completed in 1949 and the Luftwaffe rearmament program was to have matured in 1942, with a force capable of strategic bombing with heavy bombers.

The construction and training of motorized forces and a full

mobilization of the rail networks would not begin until 1943 and 1944

respectively.

Hitler needed to avoid war until these projects were complete but his

misjudgements in 1939 forced Germany into war before rearmament was

complete.

After the war, Albert Speer

claimed that the German economy achieved greater armaments output, not

because of diversions of capacity from civilian to military industry but

through streamlining of the economy. Richard Overy pointed out some 23

percent of German output was military by 1939. Between 1937 and 1939, 70

percent of investment capital went into the rubber, synthetic fuel,

aircraft and shipbuilding industries. Hermann Göring had consistently

stated that the task of the Four Year Plan

was to rearm Germany for total war. Hitler's correspondence with his

economists also reveals that his intent was to wage war in 1943–1945,

when the resources of central Europe had been absorbed into Nazi

Germany.

Living standards were not high in the late 1930s. Consumption of

consumer goods had fallen from 71 percent in 1928 to 59 percent in 1938.

The demands of the war economy reduced the amount of spending in

non-military sectors to satisfy the demand for the armed forces. On 9

September, Göring as Head of the Reich Defense Council, called

for complete "employment" of living and fighting power of the national

economy for the duration of the war. Overy presents this as evidence

that a "blitzkrieg economy" did not exist.

Adam Tooze wrote that the German economy was being prepared for a

long war. The expenditure for this war was extensive and put the

economy under severe strain. The German leadership were concerned less

with how to balance the civilian economy and the needs of civilian

consumption but to figure out how to best prepare the economy for total

war. Once war had begun, Hitler urged his economic experts to abandon

caution and expend all available resources on the war effort but the

expansion plans only gradually gained momentum in 1941. Tooze wrote that

the huge armament plans in the pre-war period did not indicate any

clear-sighted blitzkrieg economy or strategy.

Heer

Frieser wrote that the Heer (German pronunciation: [ˈheːɐ̯])

was not ready for blitzkrieg at the start of the war. A blitzkrieg

method called for a young, highly skilled mechanized army. In 1939–40,

45 percent of the army was 40 years old and 50 percent of the soldiers

had only a few weeks' training. The German army, contrary to the

blitzkrieg legend, was not fully motorized and had only 120,000

vehicles, compared to the 300,000 of the French Army. The British also

had an "enviable" contingent of motorized forces. Thus, "the image of

the German 'Blitzkrieg' army is a figment of propaganda imagination".

During the First World War the German army used 1.4 million horses for

transport and in the Second World War used 2.7 million horses; only ten

percent of the army was motorized in 1940.

Half of the German divisions available in 1940 were combat ready

but less well-equipped than the British and French or the Imperial

German Army of 1914. In the spring of 1940, the German army was

semi-modern, in which a small number of well-equipped and "elite"

divisions were offset by many second and third rate divisions".

In 2003, John Mosier wrote that while the French soldiers in 1940 were

better trained than German soldiers, as were the Americans later and

that the German army was the least mechanized of the major armies, its

leadership cadres were larger and better and that the high standard of

leadership was the main reason for the successes of the German army in

World War II, as it had been in World War I.

Luftwaffe

James Corum wrote that it was a myth that the Luftwaffe had a doctrine of terror bombing, in which civilians were attacked to break the will or aid the collapse of an enemy, by the Luftwaffe in Blitzkrieg operations. After the bombing of Guernica in 1937 and the Rotterdam Blitz in 1940, it was commonly assumed that terror bombing was a part of Luftwaffe doctrine. During the interwar period the Luftwaffe leadership rejected the concept of terror bombing in favor of battlefield support and interdiction operations.

The vital industries and

transportation centers that would be targeted for shutdown were valid

military targets. Civilians were not to be targeted directly, but the

breakdown of production would affect their morale and will to fight.

German legal scholars of the 1930s carefully worked out guidelines for

what type of bombing was permissible under international law. While

direct attacks against civilians were ruled out as "terror bombing", the

concept of the attacking the vital war industries – and probable heavy

civilian casualties and breakdown of civilian morale – was ruled as

acceptable.

Corum continues: General Walther Wever compiled a doctrine known as The Conduct of the Aerial War. This document, which the Luftwaffe adopted, rejected Giulio Douhet's

theory of terror bombing. Terror bombing was deemed to be

"counter-productive", increasing rather than destroying the enemy's will

to resist. Such bombing campaigns were regarded as diversion from the Luftwaffe's main operations; destruction of the enemy armed forces. The bombings of Guernica, Rotterdam and Warsaw were tactical missions in support of military operations and were not intended as strategic terror attacks.

J. P. Harris wrote that most Luftwaffe leaders from Goering

through the general staff believed (as did their counterparts in Britain

and the United States) that strategic bombing was the chief mission of

the air force and that given such a role, the Luftwaffe would win the

next war and that

Nearly all lectures concerned the

strategic uses of airpower; virtually none discussed tactical

co-operation with the Army. Similarly in the military journals, emphasis

centred on 'strategic' bombing. The prestigious

Militärwissenschaftliche Rundschau, the War Ministry's journal, which

was founded in 1936, published a number of theoretical pieces on future

developments in air warfare. Nearly all discussed the use of strategic

airpower, some emphasising that aspect of air warfare to the exclusion

of others. One author commented that European military powers were

increasingly making the bomber force the heart of their airpower. The

manoeuvrability and technical capability of the next generation of

bombers would be 'as unstoppable as the flight of a shell.

The Luftwaffe did end up with an air force consisting mainly of

relatively short-range aircraft, but this does not prove that the German

air force was solely interested in 'tactical' bombing. It happened

because the German aircraft industry lacked the experience to build a

long-range bomber fleet quickly, and because Hitler was insistent on the

very rapid creation of a numerically large force. It is also

significant that Germany's position in the center of Europe to a large

extent obviated the need to make a clear distinction between bombers

suitable only for 'tactical' and those necessary for strategic purposes

in the early stages of a likely future war.

Fuller and Liddell Hart

British theorists John Frederick Charles Fuller and Captain Basil Henry Liddell Hart

have often been associated with the development of blitzkrieg, though

this is a matter of controversy. In recent years historians have

uncovered that Liddell Hart distorted and falsified facts to make it

appear as if his ideas were adopted. After the war Liddell Hart imposed

his own perceptions, after the event, claiming that the mobile tank

warfare practiced by the Wehrmacht was a result of his influence.

By manipulation and contrivance, Liddell Hart distorted the actual

circumstances of the blitzkrieg formation, and he obscured its origins.

Through his indoctrinated idealization of an ostentatious concept, he

reinforced the myth of blitzkrieg. By imposing, retrospectively, his own

perceptions of mobile warfare upon the shallow concept of blitzkrieg,

he "created a theoretical imbroglio that has taken 40 years to unravel."

Blitzkrieg was not an official doctrine and historians in recent times

have come to the conclusion that it did not exist as such.

It was the opposite of a doctrine.

Blitzkrieg consisted of an avalanche of actions that were sorted out

less by design and more by success. In hindsight—and with some help from

Liddell Hart—this torrent of action was squeezed into something it

never was: an operational design.

The early 1950s literature transformed blitzkrieg into a historical

military doctrine, which carried the signature of Liddell Hart and

Guderian. The main evidence of Liddell Hart's deceit and "tendentious"

report of history can be found in his letters to Erich von Manstein, Heinz Guderian and the relatives and associates of Erwin Rommel.

Liddell Hart, in letters to Guderian, "imposed his own fabricated

version of blitzkrieg on the latter and compelled him to proclaim it as

original formula". Kenneth Macksey

found Liddell Hart's original letters to Guderian in the General's

papers, requesting that Guderian give him credit for "impressing him"

with his ideas of armored warfare. When Liddell Hart was questioned

about this in 1968 and the discrepancy between the English and German

editions of Guderian's memoirs, "he gave a conveniently unhelpful though

strictly truthful reply. ('There is nothing about the matter in my file

of correspondence with Guderian himself except...that I thanked

him...for what he said in that additional paragraph'.)".

During World War I, Fuller had been a staff officer attached to the new tank corps. He developed Plan 1919

for massive, independent tank operations, which he claimed were

subsequently studied by the German military. It is variously argued that

Fuller's wartime plans and post-war writings were an inspiration or

that his readership was low and German experiences during the war

received more attention. The German view of themselves as the losers of

the war, may be linked to the senior and experienced officers'

undertaking a thorough review, studying and rewriting of all their Army

doctrine and training manuals.

Fuller and Liddell Hart were "outsiders": Liddell Hart was unable

to serve as a soldier after 1916 after being gassed on the Somme and

Fuller's abrasive personality resulted in his premature retirement in

1933. Their views had limited impact in the British army; the War Office permitted the formation of an Experimental Mechanized Force on 1 May 1927, composed of tanks, motorized infantry, self-propelled artillery

and motorized engineers but the force was disbanded in 1928 on the

grounds that it had served its purpose. A new experimental brigade was

intended for the next year and became a permanent formation in 1933,

during the cuts of the 1932/33–1934/35 financial years.

Continuity

It has been argued that blitzkrieg was not new; the Germans did not invent something called blitzkrieg in the 1920s and 1930s. Rather the German concept of wars of movement and concentrated force were seen in wars of Prussia and the German wars of unification. The first European general to introduce rapid movement, concentrated power and integrated military effort was Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus during the Thirty Years' War.

The appearance of the aircraft and tank in the First World War, called

an RMA, offered the German military a chance to get back to the

traditional war of movement as practiced by Moltke the Elder. The so-called "blitzkrieg campaigns" of 1939 – circa 1942, were well within that operational context.

At the outbreak of war, the German army had no radically new

theory of war. The operational thinking of the German army had not

changed significantly since the First World War or since the late 19th

century. J. P. Harris and Robert M. Citino

point out that the Germans had always had a marked preference for

short, decisive campaigns – but were unable to achieve short-order

victories in First World War conditions. The transformation from the

stalemate of the First World War into tremendous initial operational and

strategic success in the Second, was partly the employment of a

relatively small number of mechanized divisions, most importantly the

Panzer divisions, and the support of an exceptionally powerful air force.

Guderian

Heinz

Guderian is widely regarded as being highly influential in developing

the military methods of warfare used by Germany's tank men at the start

of the Second World War. This style of warfare brought maneuver back to

the fore, and placed an emphasis on the offensive. This style, along

with the shockingly rapid collapse in the armies that opposed it, came

to be branded as blitzkrieg warfare.

Following Germany's military reforms of the 1920s, Heinz Guderian

emerged as a strong proponent of mechanized forces. Within the

Inspectorate of Transport Troops, Guderian and colleagues performed

theoretical and field exercise work. Guderian met with opposition from

some in the General Staff, who were distrustful of the new weapons and

who continued to view the infantry as the primary weapon of the army.

Among them, Guderian claimed, was Chief of the General Staff Ludwig Beck

(1935–38), who he alleged was skeptical that armored forces could be

decisive. This claim has been disputed by later historians. James Corum

wrote:

Guderian expressed a hearty

contempt for General Ludwig Beck, chief of the General Staff from 1935

to 1938, whom he characterized as hostile to ideas of modern mechanised

warfare: [Corum quoting Guderian] "He [Beck] was a paralysing element

wherever he appeared....[S]ignificantly of his way of thought was his

much-boosted method of fighting which he called delaying defence". This

is a crude caricature of a highly competent general who authored Army

Regulation 300 (Troop Leadership) in 1933, the primary tactical manual

of the German Army in World War II, and under whose direction the first

three panzer divisions were created in 1935, the largest such force in

the world of the time.

By Guderian's account he single-handedly created the German tactical

and operational methodology. Between 1922 and 1928 Guderian wrote a

number of articles concerning military movement. As the ideas of making

use of the combustible engine in a protected encasement to bring

mobility back to warfare developed in the German army, Guderian was a

leading proponent of the formations that would be used for this purpose.

He was later asked to write an explanatory book, which was titled Achtung Panzer! (1937). In it he explained the theories of the tank men and defended them.

Guderian argued that the tank would be the decisive weapon of the

next war. "If the tanks succeed, then victory follows", he wrote. In an

article addressed to critics of tank warfare, he wrote "until our

critics can produce some new and better method of making a successful

land attack other than self-massacre, we shall continue to maintain our

beliefs that tanks—properly employed, needless to say—are today the best

means available for land attack." Addressing the faster rate at which

defenders could reinforce an area than attackers could penetrate it

during the First World War, Guderian wrote that "since reserve forces

will now be motorized, the building up of new defensive fronts is easier

than it used to be; the chances of an offensive based on the timetable

of artillery and infantry co-operation are, as a result, even slighter

today than they were in the last war." He continued, "We believe that by

attacking with tanks we can achieve a higher rate of movement than has

been hitherto obtainable, and—what is perhaps even more important—that

we can keep moving once a breakthrough has been made." Guderian additionally required that tactical radios be widely used to

facilitate coordination and command by having one installed in all

tanks.

Guderian's leadership was supported, fostered and

institutionalized by his supporters in the Reichswehr General Staff

system, which worked the Army to greater and greater levels of

capability through massive and systematic Movement Warfare war games in

the 1930s. Guderian's book incorporated the work of theorists such as Ludwig Ritter von Eimannsberger, whose book, The Tank War (Der Kampfwagenkrieg)

(1934) gained a wide audience in the German army. Another German

theorist, Ernst Volckheim, wrote a huge amount on tank and combined arms

tactics and was influential to German thinking on the use of armored

formations but his work was not acknowledged in Guderian's writings.