The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) was a two-phase United Nations-sponsored summit on information, communication and, in broad terms, the information society that took place in 2003 in Geneva and in 2005 in Tunis. WSIS Forums have taken place periodically since then. One of the Summit's chief aims is to bridge the global digital divide separating rich countries from poor countries by increasing internet accessibility in the developing world. The conferences established 17 May as World Information Society Day.

The WSIS+10 Process marked the ten-year milestone since the 2005 Summit. In 2015, the stocktaking process culminated with a High-Level meeting of the UN General Assembly on 15 and 16 December in New York.

Background

In the last decades of the 20th century, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has changed modern society in many ways. This is often referred to as the digital revolution, and along with it have come new opportunities and threats. Many world leaders hope to use ICT to solve societal problems; yet, at the same time, there are concerns about the digital digital divide, both international level and domestic levels. This trend could lead to shaping new classes of those who have access to ICT and those who do not.

Recognizing that these challenges and opportunities require global discussion on the highest level, the government of Tunisia made a proposal at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Plenipotentiary Conference in Minneapolis in 1998 to hold a World Summit on the Information Society. This resolution was then put forward it to the United Nations. In 2001, the ITU Council decided to hold the Summit in two phases, the first from 10 to 12 December 2003, in Geneva, and the second from 16 to 18 November 2005 in Tunis.

On 21 December 2001, the United Nations General Assembly by approving Resolution 56/183 endorsed the holding of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) to discuss on information society opportunities and challenges. According to this resolution, the General Assembly related the Summit to the United Nations Millennium Declaration to implement ICT to facilitate achieving Millennium Development Goals. It also emphasized on the multi-stakeholder approach to use all stakeholders including civil society and private sector beside the governments. The resolution gave ITU the leading managerial role to organize the event in cooperation with other UN bodies as well as the other international organizations and the host countries and recommended that preparations for the Summit take place through an open-ended intergovernmental Preparatory Committee – or PrepCom – that would define the agenda of the Summit, decide on the modalities of the participation of other stakeholders, and finalize both the draft Declaration of Principles and the draft Plan of Action.

Geneva Summit, 2003

In 2003 at Geneva, delegates from 175 countries took part in the first phase of WSIS where they adopted a Declaration of Principles. This is a road map for achieving an information society accessible to all and based on shared knowledge. A Plan of Action sets out a goal of bringing 50 percent of the world's population online by 2015. It does not spell out any specifics of how this might be achieved. The Geneva summit also left unresolved more controversial issues, including the question of Internet governance and funding.

When the 2003 summit failed to agree on the future of Internet governance, the Working Group on Internet Governance (WGIG) was formed to come up with ideas on how to progress.

Civil Society delegates from NGOs produced a document called "Shaping Information Societies for Human Needs" that brought together a wide range of issues under a human rights and communication rights umbrella.

According to the Geneva Plan of Action the WSIS Action Lines are as follows:

- C1. The role of public governance authorities and all stakeholders in the promotion of ICTs for development

- C2. Information and communication infrastructure

- C3. Access to information and knowledge

- C4. Capacity building

- C5. Building confidence and security in the use of ICTs

- C6. Enabling environment

- C7. ICT Applications:

- E-government

- E-business

- E-learning

- E-health

- E-employment

- E-environment

- E-agriculture

- E-science

- C8. Cultural diversity and identity, linguistic diversity and local content

- C9. Media

- C10. Ethical dimensions of the Information Society

- C11. International and regional cooperation

Tunis Summit, 2005

The second phase took place from 16 through 18 November 2005, in Tunis, Tunisia. It resulted in agreement on the Tunis Commitment and the Tunis Agenda for the Information Society, and the creation of the Internet Governance Forum.

Just on the eve of the November 2005 Tunis event, the Association for Progressive Communications came out with its stand. (APC is an international network of civil society organizations—whose goal is to empower and support groups and individuals working for peace, human rights, development and protection of the environment, through the strategic use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), including the internet).

APC said it had participated extensively in the internet governance process at the World Summit on Information Society. It says: Out of this participation and in collaboration with other partners, including members of the WSIS civil society internet governance caucus, APC has crystallized a set of recommendations with regard to internet governance ahead of the final Summit in Tunis in November 2005. APC proposed specific actions in each of the following five areas:

- The establishment of an Internet Governance Forum;

- The transformation of ICANN into a global body with full authority over DNS management, and an appropriate form of accountability to its stakeholders in government, private sector, and civil society;

- The initiation of a multi-stakeholder convention on internet governance and universal human rights that will codify the basic rights applicable to the internet, which will be legally binding in international law with particular emphasis on clauses in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights directly relevant to the internet, such as the rights to freedom of expression, association, and privacy.

- Ensuring internet access is universal and affordable. APC argued: "The internet is a global public space that should be open and accessible to all on a non-discriminatory basis. The internet, therefore, must be seen as a global public infrastructure. In this regard we recognize the internet to be a global public good related to the concept of the common heritage of humanity and access to it is in the public interest, and must be provided as a global public commitment to equality".

- Measures to promote capacity building in "developing" countries with regard to increasing "developing" country participation in global public policy forums on internet governance.

The summit itself attracted 1,500 people from International Organizations, 6,200 from NGOs, 4,800 from the private sector, and 980 from the media.

Funding for the event was provided by several countries. The largest donations to the 2003 event came from Japan and Spain. The 2005 event received funding from Japan, Sweden, France and many other countries as well as companies like Nokia.

Conference developments

A dispute over control of the Internet threatened to derail the conference. However, a last-minute decision to leave control in the hands of the United States-based ICANN for the time being avoided a major blow-up. As a compromise there was also an agreement to set up an international Internet Governance Forum and Enhanced Cooperation, with a purely consultative role.

The summit itself was marred by criticism of Tunisia for allowing attacks on journalists and human rights defenders to occur in the days leading up to the event. The Tunisian government tried to prevent one of the scheduled sessions, "Expression Under Repression", from happening. French reporter Robert Ménard, the president of Reporters sans frontières, (Reporters Without Borders) was refused admission to Tunisia for phase two of the Summit. A French journalist for Libération was stabbed and beaten by unidentified men after he reported on local human rights protesters. The representatives of the Human Rights in China NGO (due to Chinese government pressure on Tunisia) were refused entry to Tunisia. A Belgian television crew was harassed and forced to hand over footage of Tunisian dissidents. Local human rights defenders were roughed up and prevented from organizing a meeting with international civil society groups.

Stocktaking process

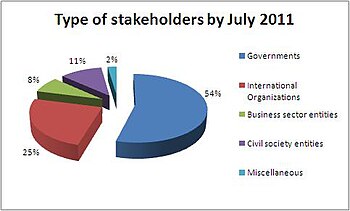

The WSIS stocktaking process is a follow-up to WSIS. Its purpose is to provide a register of activities carried out by governments, international organizations, the business sector, civil society and other entities, in order to highlight the progress made since the landmark event. Following § 120 of TAIS, ITU has been maintaining the WSIS Stocktaking database as a publicly accessible system providing information on ICT-related initiatives and projects with reference to the 11 WSIS Action Lines.

ECOSOC Resolution 2010/12 on "Assessment of the progress made in the implementation of and follow-up to the outcomes of the World Summit on the Information Society" reiterated the importance of maintaining a process for coordinating the multi-stakeholder implementation of WSIS outcomes through effective tools, with the goal of exchanging of information among WSIS Action Line Facilitators; identification of issues that need improvements; and discussion of the modalities of reporting the overall implementation process. The resolution encourages all WSIS stakeholders to continue to contribute information to the WSIS Stocktaking database (www.wsis.org/stocktaking).

Furthermore, regular reporting on WSIS Stocktaking is the outcome of the Tunis phase of the Summit, which was launched in order to serve as a tool for assisting with the WSIS follow-up. The purpose of the regular reports is to update stakeholders on the various activities related to the 11 Action Lines identified in the Geneva Plan of Action, that was approved during First Phase of the WSIS.

Platform

The WSIS stocktaking platform is the new initiative that was launched by Mr Zhao, ITU Deputy Secretary-General and chair of ITU's WSIS Task Force, in February 2010 to improve existing functionalities and transform the former static database into a portal to highlight ICT-related projects and initiatives in line with WSIS implementation. The platform offers stakeholders interactive networking opportunities via Web 2.0 applications. In the framework of the WSIS Stocktaking Platform, all types of stakeholders can benefit from the "Global Events Calendar", "Global Publication Repository", "Case Studies" and other components that tend to extend networking and create partnerships in order to provide more visibility and add value to projects at the local, national, regional and international levels.

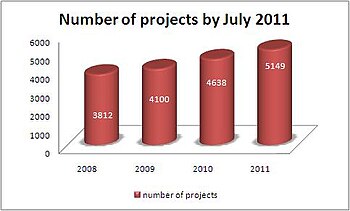

Since the first edition of the WSIS Stocktaking Report was issued in 2005, biannual reporting has been a key tool for monitoring the progress of ICT initiatives and projects worldwide. The 2012 report reflects more than 1,000 recent WSIS-related activities, undertaken between May 2010 and 2012, each emphasizing the efforts deployed by stakeholders involved in the WSIS process.

Forum and follow-up

The WSIS follow-up works towards achieving the indicative targets, set out in the Geneva Plan of Action and serve as global references for improving connectivity and universal, ubiquitous, equitable, non-discriminatory and affordable access to, and use of, ICTs, considering different national circumstances, to be achieved by 2015, and to using ICTs, as a tool to achieve the internationally agreed development goals and objectives, including the Millennium Development Goals.

Since 2006 the WSIS Forum has been held in Geneva around World Information Society Day (17 May) to implement the WSIS Follow up. The event is organized by the WSIS facilitators including ITU, UNESCO, UNCTAD and UNDP and hosted by ITU. Until 2010 the Forum was held in ITU building and since then it has been held in International Labour Organization building. Every year the Forum attracts more than 1000 WSIS Stakeholders from more than 140 countries. Several high-level representatives of the wider WSIS Stakeholder community graced the Forum, more than 20 Ministers and Deputies, several Ambassadors, CEOs and Civil Society leaders contributed passionately towards the programme of the Forum. Remote participation was an integral component of the WSIS Forum over 1000 stakeholders followed and contributed to the outcomes of the event in a remote manner from all parts of world. Onsite networking was facilitated by the imeetYouatWSIS online community platform. More than 250 on-site participants have actively used the tool prior and during the event which facilitated in fruitful networking leading to win-win partnerships.

WSIS Forum meetings were held in Geneva as follows:

- WSIS Forum 2006: 9–19 May

- WSIS Forum 2007: 14–25 May

- WSIS Forum 2008: 13–23 May

- WSIS Forum 2009: 18–22 May

- WSIS Forum 2010: 10–14 May

- WSIS Forum 2011: 16–20 May

- WSIS Forum 2012: 14–18 May

- WSIS Forum 2013: 13–17 May

- WSIS+10 High Level Event: 9 to 12 June 2014

- WSIS Forum 2015: 25–29 May 2015

Prizes

This initiative responds to the requests of participants of WSIS Forum 2011 for a mechanism to evaluate and reward stakeholders for the success of their efforts in implementing development-oriented strategies that leverage the power of information and communication technologies (ICTs). The first WSIS Project Prizes were awarded in 2012 and have been awarded each year thereafter.

The prizes provide a unique recognition for excellence in the implementation of WSIS outcomes. The contest is open to all stakeholders: governments, private sector, civil society, international organizations, academia, and others. The 18 prize categories are linked to the WSIS Action Lines outlined in the Geneva Plan of Action. The annual contest is organized into four phases: (1) Submission of project descriptions; (2) Voting by the members of the WSIS Stocktaking Platform; (3) Compilation of extended descriptions of the winning projects and preparation of "WSIS Stocktaking: Success Stories"; and (4) the WSIS Project Prize Ceremony and release of the "Success Stories" publication at the WSIS Forum. The WSIS Project Prizes are now an integral part of the WSIS Stocktaking Process established in 2004.

WSIS+10

The WSIS+10 High-Level Event, an extended version of the WSIS Forum, took place 9–13 June 2014 in Geneva, Switzerland. The event reviewed the progress made in the implementation of the WSIS outcomes under the mandates of participating agencies, took stock of developments in the last 10 years based on reports of WSIS stakeholders, including those submitted by countries, action line facilitators, and other stakeholders. The event reviewed the WSIS Outcomes (2003 and 2005) related to the WSIS Action Lines and agreed a vision on how to proceed beyond 2015.

The WSIS+10 High-Level Event endorsed the "WSIS+10 Statement on Implementation of WSIS Outcomes" and the "WSIS+10 Vision for WSIS Beyond 2015". These outcome documents were developed in an open and inclusive preparatory process, the WSIS+10 Multistakeholder Preparatory Platform (WSIS+10 MPP). "High-Level Track Policy Statements" and a "Forum Track Outcome Document" are also available.

The WSIS+10 open consultation process was an open and inclusive consultation among WSIS stakeholders to prepare for the WSIS + 10 High-Level Event. It focused on developing multistakeholder consensus on two draft outcome documents. Eight open consultation meetings among stakeholders, including governments, private sector, civil society, international organizations, and relevant regional organizations, were held between July 2013 and June 2014. Two draft outcome documents were developed and submitted for consideration at the WSIS+10 High-Level Event:

- Draft WSIS+10 Statement on the Implementation of WSIS Outcomes.

- Draft WSIS+10 Vision for WSIS Beyond 2015 under mandates of participating agencies.

The final WSIS+10 High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly took place on 15–16 December 2015 in New York, and concluded with the adoption of the Outcome Document of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the overall review of the implementation of the outcomes of the World Summit on the Information Society was adopted.

Civil society

A number of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), scientific institutions, community media and others participated as "civil society" in the preparations for the summit as well as the High Level Event itself, drawing attention to human rights, people-centered development, freedom of speech and press freedom.

Youth and civil society representatives played key roles in the whole WSIS process. Young leaders from different countries, notably Nick and Alex Fielding from Canada, Tarek from Tunisia, and Mr. Zeeshan Shoki from Pakistan were the active and founding members of the Global WSIS Youth Caucus having founded youth caucuses in their home countries: Canada WSIS Youth Caucus, Tunisia WSIS Youth Caucus, and Pakistan WSIS Youth Caucus. Young leaders participated in both the Geneva and Tunis phases. Youth Day was celebrated and youth showcased their projects and organised events at the summit. Youth also participated in the preparation of the WSIS Declaration and Plan of Action.

In Germany, a WSIS working group initiated by the Network New Media and the Heinrich Böll Foundation, has been meeting continuously since mid-2002.

Similarly in Pakistan, PAK Education Society/Pakistan Development Network had taken the initiative to build Pakistan Knowledge Economy or Information Society. It has honour to be pioneer in promoting ICT in Pakistan and was the only Pakistani NGO who participated in UN World Summit on Information Society, Geneva and also organised Seminar at ICT4 Development Platform. The Idea of Third World Silicon Valley was also conceptualised.

One of the most significant results of civil society participation in the WSIS first phase was the insertion, in the final declaration signed by the nation's delegates, of the clear distinction between three societal model of digitally-driven increase in awareness : proprietary, open-source and free software based models. It is the result of the work led by Francis Muguet as co-chair of Patent, Copyrights and Trademark working group.

Some civil society groups expressed alarm that the 2005 phase of the WSIS was being held in Tunisia, a country with serious human rights violations. A fact-finding mission to Tunisia in January 2005 by the Tunisia Monitoring Group (TMG), a coalition of 14 members of the International Freedom of Expression Exchange, found serious cause for concern about the current state of freedom of expression and of civil liberties in the country, including gross restrictions on freedom of the press, media, publishing and the Internet.

The coalition published a 60-page report that recommends steps the Tunisian government needs to take to bring the country in line with international human rights standards. At the third WSIS Preparatory Committee meeting in Geneva in September 2005, the TMG launched an update to the report that found no improvements in the human rights situation.

The Digital Solidarity Fund, an independent body aiming to reduce the digital divide, was established following discussions which took place during the Tunis summit in 2005.

Digital divide and digital dilemma

Two main concerns seemed to be the issue and talk of the UN World Summit on the Information Society held in Tunis, (i) the digital divide and (ii) the digital dilemma.

First the digital divide, which was addressed in Archbishop John P. Foley's address before the WSIS and in the Vatican document, Ethics in the Internet. According to Archbishop Foley the digital divide is the current disparity in the access to digital communications between developed and developing countries and it requires the joint effort of the entire international community. The digital divide is considered a form of discrimination dividing the rich and the poor, both within and among nations, on the basis of access, or lack of access, to the new information technology. It is an updated version of an older gap that has always existed between the information rich and the information poor. The term digital divide underlines the reality that not only individuals and groups but also nations must have access to the new technology in order to share in the promised benefits of globalization and not fall behind other nations.

In a statement delivered by Senator Burchell Whiteman from Jamaica he stressed that Jamaica realizes the importance of bridging the digital divide which he sees as promoting social and economic development for 80% of the countries that are still struggling with this gap and the impact that it has on them. In a statement given by Mr. Ignacio Gonzalez Planas, who is the minister of Informatics and Communications of the Republic of Cuba, he also talked about the concern of only a few countries enjoying these privileges. Mentioning that over half of the world population does not have telephone access, which was invented more than a century ago. A statement by Vice Premier Huang Ju, the State Council of the People's Republic of China, said that the information society should be a people centered society in which all peoples and all countries share the benefit to the fullest in greater common development in the information society.

Second the digital dilemma, which the Holy See emphasized as a disadvantage to the information society and urged caution to avoid taking the wrong steps. It is a real and present danger with technology especially the Internet. The Holy See strongly supports freedom of expression and the free exchange of ideas, but argues that the moral order and common good must be respected. One must approach it with sensitivity and respect for other people's values and beliefs and protect the distinctiveness of cultures and the underlying unity of the human family.

Whiteman from Jamaica agreed on the issue of facing digital dilemmas as well. He stated that information resources combined with technology resources are available to the world and they have the power to transform the world for good or ill. In a statement made by Mr. Stjepan Mesic, President of Croatia, it was stated that we are flooded with data and we think that we know and can find everything about everyone but we also must remember that we don't know what so easily accessible is like. He states that although the information society is a blessing one should not ignore the potentiality of it turning into a nightmare.

The Holy See's caution of the information society is being heard and echoed by other countries especially those that were present at the WSIS in Tunis.[who?] Echoing the statement made in Ethics in the Internet, "The internet can make an enormously valuable contribution to human life. It can foster prosperity and peace, intellectual and aesthetic growth, mutual understanding among peoples and nations on a global scale."

In a press statement released 14 November 2003 the Civil Society group warned about a deadlock, already setting in on the very first article of the declaration, where governments are not able to agree on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as the common foundation of the summit declaration. It identified two main problems:

- On the issue of correcting imbalances in riches, rights and power, governments do not agree on even the principle of a financial effort to overcome the so-called "digital divide", which was precisely the objective when the summit process was started in 2001.

- In its view, not even the basis of human life in dignity and equality, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, finds support as the basis for the Information Society. Governments are not able to agree on a commitment to basic human right standards as the basis for the Information Society, most prominent in this case being the freedom of expression.

The "digital divide" concept was criticized by some civil society groups as well. For instance, the Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure (FFII) rejected the term.

Internet governance

The Summit's first phase took place in December 2003 in Geneva. The summit process began with the first "Prepcom" in July 2002. The last Prepcom, held from 19 to 30 September 2005 in Geneva, ended without securing final agreement on Internet governance, with the U.S. rejecting a European Union proposal to relinquish control of ICANN.

An issue that emerged was Internet governance and the dominant role that the USA plays in policy making. The most radical ideas about devolving this authority were those supporting a civil society approach to Internet governance.

In a document released on 3 December 2003 the United States delegation to the WSIS advocated a strong private sector and rule of law as the critical foundations for development of national information and communication technologies (ICT). Ambassador David Gross, the US coordinator for international communications and information policy, outlined what he called "the three pillars" of the US position in a briefing to reporters 3 December.

- As nations attempt to build a sustainable ICT sector, commitment to the private sector and rule of law must be emphasized, Gross said, "so that countries can attract the necessary private investment to create the infrastructure."

- A second important pillar of the US position was the need for content creation and intellectual property rights protection in order to inspire ongoing content development.

- Ensuring security on the internet, in electronic communications and in electronic commerce was the third major priority for the US. "All of this works and is exciting for people as long as people feel that the networks are secure from cyber attacks, secure in terms of their privacy," Gross said.

As the Geneva phase of the meeting drew closer, one proposal that was gaining attention was to create an international fund to provide increased financial resources to help lesser-developed nations expand their ICT sectors. The "voluntary digital solidarity fund" was a proposal put forth by the president of Senegal, but it was not one that the United States could currently endorse, Gross said.

Gross said the United States was also achieving broad consensus on the principle that a "culture of cybersecurity" must develop in national ICT policies to continue growth and expansion in this area. He said the last few years had been marked by considerable progress as nations update their laws to address the galloping criminal threats in cyberspace. "There's capacity-building for countries to be able to criminalize those activities that occur within their borders...and similarly to work internationally to communicate between administrations of law enforcement to track down people who are acting in ways that are unlawful," Gross said.

Many governments are very concerned that various groups use U.S.-based servers to spread anti-semitic, nationalist, or regime critical messages. This controversy is a consequence of the American position on free speech which does not consider speech as criminal without direct appeals to violence. The United States argues that giving the control of Internet domain names to international bureaucrats and governments may lead to massive censorship that could destroy the freedom of the Internet as a public space.

Ultimately, the US Department of Commerce made it clear it intends to retain control of the Internet's root servers indefinitely.

The main UN level body in this field is the Internet Governance Forum, which was established in 2006.

Selected media responses

A report by Brenda Zulu for The Times of Zambia explained that the (Dakar) resolution "generated a lot of discussion since it was very different from the Accra resolution, which advocated change from the status quo where Zambia participated in the Africa WSIS in Accra. The Dakar resolutions, in the main, advocated the status quo although it did not refer to internationalization of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)."

The Jamaica Observer had a column which saw Cyberspace as backyard for the new 'Monroe Doctrine'. The Monroe Doctrine, expressed in 1823, proclaimed that the Americas should be closed to future European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. The Doctrine was conceived by its authors, especially John Quincy Adams, as a proclamation by the United States of moral opposition to colonialism, but has subsequently been re-interpreted in a wide variety of ways, including by President Theodore Roosevelt as a license for the U.S. to practice its own form of colonialism.

From India, The Financial Express interviewed Nitin Desai, who is special advisor to the United Nations Secretary General. Desai is quoted saying, "Our main goal is to find ways for developing countries to gain better access to the Internet and information and communication technologies (ICTs), helping them improve their life standards right from their knowledge base to their work culture, and spread awareness about diseases and other crucial issues. This will aim to bridge the huge communication technology and infrastructure gap existing currently in the world. This will include connecting villages, community access points, schools and universities, research centers, libraries, health centers and hospitals, and local and central government departments. Besides looking at the first two years of implementation of the Plan of Action after the Geneva summit, the Tunis episode will seek to encourage the development of content meant to empower the nations."

The Association for Progressive Communications criticizes Desai's view: "He says: 'The way India has made use of IT, fetching the country not only profits, but a huge percentage of employed people, it has been really impressive.' My view: it's a shame that we in India have so many IT professionals, but these skills get used so much for the export-dollar, and hardly at all (except in a spillover manner) to tackle the huge issues that a billion seeking a better life have to daily deal with."

The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), had a Reuters report titled 'Rights groups says Tunisia is not right for WSIS', citing the position of the IFEX Tunisia Monitoring Group. It said:

As thousands of delegates and InfoTech experts gathered in Tunisia this weekend for a UN World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), human rights and media freedom groups were asking: Is this meeting in the wrong place?" and points to both the positions critical of the Tunisian government on free speech, and the administration's defense of its record. Finally, when it comes to reporting on the unfair global village, and communication rights we have within it, isn't it ironic that the awareness and ability to keep up with the issue – of information – is itself so unfair?