African National Congress | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | ANC |

| President | Cyril Ramaphosa |

| Chairperson | Gwede Mantashe |

| Secretary-General | Ace Magashule (suspended) |

| Presidium | National Executive Committee |

| Spokesperson | Pule Mabe |

| Deputy President | David Mabuza |

| Deputy Secretary General | vacant |

| Treasurer General | Paul Mashatile |

| Founders | |

| Founded | 8 January 1912 |

| Legalised | 3 February 1990 |

| Headquarters | Luthuli House 54 Sauer Street Johannesburg Gauteng |

| Newspaper | ANC Today |

| Youth wing | ANC Youth League |

| Women's wing | ANC Women's League |

| Veteran's League | ANC Veterans League |

| Paramilitary wing | uMkhonto we Sizwe (until 1994) |

| Membership (2015) | 769,000 |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| National affiliation | Tripartite Alliance |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

| African affiliation | Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa |

| Colours |

|

| Slogan | South Africa's National Liberation Movement |

| Anthem | "Lord Bless Africa"1:45 |

| National Assembly seats | 230 / 400 |

| NCOP seats | 54 / 90 |

| Control of NCOP delegations | 8 / 9 |

| Pan-African Parliament | 3 / 5 (South African seats) |

| Provincial Legislatures | 255 / 430 |

| City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality (council) | 121 / 270 |

| Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality (council) | 50 / 120 |

| City of Cape Town (council) | 57 / 231 |

Party flag | |

| |

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election installed Nelson Mandela as President of South Africa. Cyril Ramaphosa, the incumbent national President, has served as President of the ANC since 18 December 2017.

Founded on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the organisation was formed to agitate, by moderate methods, for the rights of black South Africans. When the National Party government came to power in 1948, the ANC's central purpose became to oppose the new government's policy of institutionalised apartheid. To this end, its methods and means of organisation shifted; its adoption of the techniques of mass politics, and the swelling of its membership, culminated in the Defiance Campaign of civil disobedience in 1952–53. The ANC was banned by the South African government between April 1960 – shortly after the Sharpeville massacre – and February 1990. During this period, despite periodic attempts to revive its domestic political underground, the ANC was forced into exile by increasing state repression, which saw many of its leaders imprisoned on Robben Island. Headquartered in Lusaka, Zambia, the exiled ANC dedicated much of its attention to a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare against the apartheid state, carried out under its military wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe, which was founded in 1961 in partnership with the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC was condemned as a terrorist organisation by the governments of South Africa, the United States, and the United Kingdom. However, it positioned itself as a key player in the negotiations to end apartheid, which began in earnest after the ban was repealed in 1990.

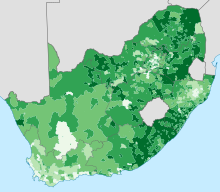

In the post-apartheid era, the ANC continues to identify itself foremost as a liberation movement, although it is also a registered political party. Partly due to its Tripartite Alliance with the SACP and the Congress of South African Trade Unions, it has retained a comfortable electoral majority at the national level and in most provinces, and has provided each of South Africa's five presidents since 1994. South Africa is considered a dominant-party state. However, the ANC's electoral majority has declined consistently since 2004, and in the most recent elections – the 2021 local elections – its share of the national vote dropped below 50% for the first time ever. Over the last decade, the party has been embroiled in a number of controversies, particularly relating to widespread allegations of political corruption among its members.

History

Origins

The ANC was founded as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in Bloemfontein on 8 January 1912, and was renamed the African National Congress in 1923. Its founding leaders were John Dube (president), Sol Plaatje (secretary), and Pixley ka Isaka Seme (treasurer), who, like much of the ANC's early membership, were drawn from the conservative, educated, and religious professional classes of black South African society. Around 1920, in a partial shift away from its early focus on the "politics of petitioning", the ANC developed a programme of passive resistance directed primarily at the expansion and entrenchment of pass laws. When Josiah Gumede took over as ANC president in 1927, he advocated for a strategy of mass mobilisation and cooperation with the Communist Party, but was voted out of office in 1930 and replaced with the traditionalist Seme, whose leadership saw the ANC's influence wane.

In the 1940s, Alfred Bitini Xuma revived some of Gumede's programmes, assisted by a surge in trade union activity and by the formation in 1944 of the left-wing ANC Youth League under a new generation of activists, among them Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, and Oliver Tambo. After the National Party was elected into government in 1948 on a platform of apartheid, entailing the further institutionalisation of racial segregation, this new generation pushed for a Programme of Action which explicitly advocated African nationalism and led the ANC, for the first time, to the sustained use of mass mobilisation techniques like strikes, stay-aways, and boycotts. This culminated in the 1952–53 Defiance Campaign, a campaign of mass civil disobedience organised by the ANC, the Indian Congress, and the coloured Franchise Action Council in protest of six apartheid laws. The ANC's membership swelled. In June 1955, it was one of the groups represented at the multi-racial Congress of the People in Kliptown, Soweto, which ratified the Freedom Charter, from then onwards a fundamental document in the anti-apartheid struggle. The Charter was the basis of the enduring Congress Alliance, but was also used as a pretext to prosecute hundreds of activists, among them most of the ANC's leadership, in the Treason Trial. Before the trial was concluded, the Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960. In the aftermath, the ANC was banned by the South African government. It was not unbanned until February 1990, almost three decades later.

Exile in Lusaka

After its banning in April 1960, the ANC was driven underground, a process hastened by a barrage of government banning orders, by an escalation of state repression, and by the imprisonment of senior ANC leaders pursuant to the Rivonia trial and Little Rivonia trial. From around 1963, the ANC effectively abandoned much of even its underground presence inside South Africa and operated almost entirely from its external mission, with headquarters first in Morogoro, Tanzania, and later in Lusaka, Zambia. For the entirety of its time in exile, the ANC was led by Tambo – first de facto, with president Albert Luthuli under house arrest in Zululand; then in an acting capacity, after Luthuli's death in 1967; and, finally, officially, after a leadership vote in 1985. Also notable about this period was the extremely close relationship between the ANC and the reconstituted South African Communist Party (SACP), which was also in exile.

uMkhonto we Sizwe

In 1961, partly in response to the Sharpeville massacre, leaders of the SACP and the ANC formed a military body, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, Spear of the Nation), as a vehicle for armed struggle against the apartheid state. Initially, MK was not an official ANC body, nor had it been directly established by the ANC National Executive: it was considered an autonomous organisation, until such time as the ANC formally recognised it as its armed wing in October 1962.

In the first half of the 1960s, MK was preoccupied with a campaign of sabotage attacks, especially bombings of unoccupied government installations. As the ANC reduced its presence inside South Africa, however, MK cadres were increasingly confined to training camps in Tanzania and neighbouring countries – with such exceptions as the Wankie Campaign, a momentous military failure. In 1969, Tambo was compelled to call the landmark Morogoro Conference to address the grievances of the rank-and-file, articulated by Chris Hani in a memorandum which depicted MK's leadership as corrupt and complacent. Although MK's malaise persisted into the 1970s, conditions for armed struggle soon improved considerably, especially after the Soweto uprising of 1976 in South Africa saw thousands of students – inspired by Black Consciousness ideas – cross the borders to seek military training. MK guerrilla activity inside South Africa increased steadily over this period, with one estimate recording an increase from 23 incidents in 1977 to 136 incidents in 1985. In the latter half of the 1980s, a number of South African civilians were killed in these attacks, a reversal of the ANC's earlier reluctance to incur civilian casualties. Fatal attacks included the 1983 Church Street bombing, the 1985 Amanzimtoti bombing, the 1986 Magoo's Bar bombing, and the 1987 Johannesburg Magistrate's Court bombing. Partly in retaliation, the South African Defence Force increasingly crossed the border to target ANC members and ANC bases, as in the 1981 raid on Maputo, 1983 raid on Maputo, and 1985 raid on Gaborone.

During this period, MK activities led the governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan to condemn the ANC as a terrorist organisation. In fact, neither the ANC nor Mandela were removed from the U.S. terror watch list until 2008. The animosity of Western regimes was partly explained by the Cold War context, and by the considerable amount of support – both financial and technical – that the ANC received from the Soviet Union.

Negotiations to end apartheid

From the mid-1980s, as international and internal opposition to apartheid mounted, elements of the ANC began to test the prospects for a negotiated settlement with the South African government, although the prudence of abandoning armed struggle was an extremely controversial topic within the organisation. Following preliminary contact between the ANC and representatives of the state, business, and civil society, President F. W. de Klerk announced in February 1990 that the government would unban the ANC and other banned political organisations, and that Mandela would be released from prison. Some ANC leaders returned to South Africa from exile for so-called "talks about talks", which led in 1990 and 1991 to a series of bilateral accords with the government establishing a mutual commitment to negotiations. Importantly, the Pretoria Minute of August 1990 included a commitment by the ANC to unilaterally suspend its armed struggle. This made possible the multi-party Convention for a Democratic South Africa and later the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum, in which the ANC was regarded as the main representative of the interests of the anti-apartheid movement.

However, ongoing political violence, which the ANC attributed to a state-sponsored third force, led to recurrent tensions. Most dramatically, after the Boipatong massacre of June 1992, the ANC announced that it was withdrawing from negotiations indefinitely. It faced further casualties in the Bisho massacre, the Shell House massacre, and in other clashes with state forces and supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). However, once negotiations resumed, they resulted in November 1993 in an interim Constitution, which governed South Africa's first democratic elections on 27 April 1994. In the elections, the ANC won an overwhelming 62.65% majority of the vote. Mandela was elected president and formed a coalition Government of National Unity, which, under the provisions of the interim Constitution, also included the National Party and IFP. The ANC has controlled the national government since then.

Breakaways

In the post-apartheid era, two significant breakaway groups have been formed by former ANC members. The first is the Congress of the People, founded by Mosiuoa Lekota in 2008 in the aftermath of the Polokwane elective conference, when the ANC declined to re-elect Thabo Mbeki as its president and instead compelled his resignation from the national presidency. The second breakaway is the Economic Freedom Fighters, founded in 2013 after youth leader Julius Malema was expelled from the ANC. Before these, the most important split in the ANC's history occurred in 1959, when Robert Sobukwe led a splinter faction of African nationalists to the new Pan Africanist Congress.

Current structure and composition

Leadership

Under the ANC constitution, every member of the ANC belongs to a local branch, and branch members select the organisation's policies and leaders. They do so primarily by electing delegates to the National Conference, which is currently convened every five years. Between conferences, the organisation is led by its 86-member National Executive Committee, which is elected at each conference. The most senior members of the National Executive Committee are the so-called Top Six officials, the ANC president primary among them. A symmetrical process occurs at the subnational levels: each of the nine provincial executive committees and regional executive committees are elected at provincial and regional elective conferences respectively, also attended by branch delegates; and branch officials are elected at branch general meetings.

Leagues

The ANC has three leagues: the Women's League, the Youth League and the Veterans' League. Under the ANC constitution, the leagues are autonomous bodies with the scope to devise their own constitutions and policies; for the purpose of national conferences, they are treated somewhat like provinces, with voting delegates and the power to nominate leadership candidates.

Tripartite Alliance

The ANC is recognised as the leader of a three-way alliance, known as the Tripartite Alliance, with the SACP and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). The alliance was formalised in mid-1990, after the ANC was unbanned, but has deeper historical roots: the SACP had worked closely with the ANC in exile, and COSATU had aligned itself with the Freedom Charter and Congress Alliance in 1987. The membership and leadership of the three organisations has traditionally overlapped significantly. The alliance constitutes a de facto electoral coalition: the SACP and COSATU do not contest in government elections, but field candidates through the ANC, hold senior positions in the ANC, and influence party policy. However, the SACP, in particular, has frequently threatened to field its own candidates, and in 2017 it did so for the first time, running against the ANC in by-elections in the Metsimaholo municipality, Free State.

Electoral candidates

Under South Africa's closed-list proportional representation electoral system, parties have immense power in selecting candidates for legislative bodies. The ANC's internal candidate selection process is overseen by so-called list committees and tends to involve a degree of broad democratic participation, especially at the local level, where ANC branches vote to nominate candidates for the local government elections. Between 2003 and 2008, the ANC also gained a significant number of members through the controversial floor crossing process, which occurred especially at the local level.

The leaders of the executive in each sphere of government – the president, the provincial premiers, and the mayors – are indirectly elected after each election. In practice, the selection of ANC candidates for these positions is highly centralised, with the ANC caucus voting together to elect a pre-decided candidate. Although the ANC does not always announce whom its caucuses intend to elect, the National Assembly has thus far always elected the ANC president as the national president.

Cadre deployment

The ANC has adhered to a formal policy of cadre deployment since 1985. In the post-apartheid era, the policy includes but is not exhausted by selection of candidates for elections and government positions: it also entails that the central organisation "deploys" ANC members to various other strategic positions in the party, state, and economy.

Ideology and policies

The ANC prides itself on being a broad church, and, like many dominant parties, resembles a catch-all party, accommodating a range of ideological tendencies. As Mandela told the Washington Post in 1990:

The ANC has never been a political party. It was formed as a parliament of the African people. Right from the start, up to now, the ANC is a coalition, if you want, of people of various political affiliations. Some will support free enterprise, others socialism. Some are conservatives, others are liberals. We are united solely by our determination to oppose racial oppression. That is the only thing that unites us. There is no question of ideology as far as the odyssey of the ANC is concerned, because any question approaching ideology would split the organization from top to bottom. Because we have no connection whatsoever except at this one, of our determination to dismantle apartheid.

The post-apartheid ANC continues to identify itself foremost as a liberation movement, pursuing "the complete liberation of the country from all forms of discrimination and national oppression". It also continues to claim the Freedom Charter of 1955 as "the basic policy document of the ANC". However, as NEC member Jeremy Cronin noted in 2007, the various broad principles of the Freedom Charter have been given different interpretations, and emphasised to differing extents, by different groups within the organisation. Nonetheless, some basic commonalities are visible in the policy and ideological preferences of the organisation's mainstream.

Non-racialism

The ANC is committed to the ideal of non-racialism and to opposing "any form of racial, tribalistic or ethnic exclusivism or chauvinism".

National Democratic Revolution

The 1969 Morogoro Conference committed the ANC to a "national democratic revolution [which] – destroying the existing social and economic relationship – will bring with it a correction of the historical injustices perpetrated against the indigenous majority and thus lay the basis for a new – and deeper internationalist – approach". For the movement's intellectuals, the concept of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR) was a means of reconciling the anti-apartheid and anti-colonial project with a second goal, that of establishing domestic and international socialism – the ANC is a member of the Socialist International, and its close partner the SACP traditionally conceives itself as a vanguard party. Specifically, and as implied by the 1969 document, NDR doctrine entails that the transformation of the domestic political system (national struggle, in Joe Slovo's phrase) is a precondition for a socialist revolution (class struggle). The concept remained important to ANC intellectuals and strategists after the end of apartheid. Indeed, the pursuit of the NDR is one of the primary objectives of the ANC as set out in its constitution. As with the Freedom Charter, the ambiguity of the NDR has allowed it to bear varying interpretations. For example, whereas SACP theorists tend to emphasise the anti-capitalist character of the NDR, some ANC policymakers have construed it as implying the empowerment of the black majority even within a market-capitalist scheme.

Economic interventionism

We must develop the capacity of government for strategic intervention in social and economic development. We must increase the capacity of the public sector to deliver improved and extended public services to all the people of South Africa.

Since 1994, consecutive ANC governments have held a strong preference for a significant degree of state intervention in the economy. The ANC's first comprehensive articulation of its post-apartheid economic policy framework was set out in the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) document of 1994, which became its electoral manifesto and also, under the same name, the flagship policy of Nelson Mandela's government. The RDP aimed both to redress the socioeconomic inequalities created by colonialism and apartheid, and to promote economic growth and development; state intervention was judged a necessary step towards both goals. Specifically, the state was to intervene in the economy through three primary channels: a land reform programme; a degree of economic planning, through industrial and trade policy; and state investments in infrastructure and the provision of basic services, including health and education. Although the RDP was abandoned in 1996, these three channels of state economic intervention have remained mainstays of subsequent ANC policy frameworks.

Neoliberal turn

In 1996, Mandela's government replaced the RDP with the Growth Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme, which was maintained under President Thabo Mbeki, Mandela's successor. GEAR has been characterised as a neoliberal policy, and it was disowned by both COSATU and the SACP. While some analysts viewed Mbeki's economic policy as undertaking the uncomfortable macroeconomic adjustments necessary for long-term growth, others – notably Patrick Bond – viewed it as a reflection of the ANC's failure to implement genuinely radical transformation after 1994. Debate about ANC commitment to redistribution on a socialist scale has continued: in 2013, the country's largest trade union, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, withdrew its support for the ANC on the basis that "the working class cannot any longer see the ANC or the SACP as its class allies in any meaningful sense". It is evident, however, that the ANC never embraced free-market capitalism, and continued to favour a mixed economy: even as the debate over GEAR raged, the ANC declared itself (in 2004) a social-democratic party, and it was at that time presiding over phenomenal expansions of its black economic empowerment programme and the system of social grants.

Developmental state

As its name suggests, the RDP emphasised state-led development – that is, a developmental state – which the ANC has typically been cautious, at least in its rhetoric, to distinguish from the neighbouring concept of a welfare state. In the mid-2000s, during Mbeki's second term, the notion of a developmental state was revived in South African political discourse when the national economy worsened; and the 2007 National Conference whole-heartedly endorsed developmentalism in its policy resolutions, calling for a state "at the centre of a mixed economy... which leads and guides that economy and which intervenes in the interest of the people as a whole". The proposed developmental state was also central to the ANC's campaign in the 2009 elections, and it remains a central pillar of the policy of the current government, which seeks to build a "capable and developmental" state. In this regard, ANC politicians often cite China as an aspirational example. A discussion document ahead of the ANC's 2015 National General Council proposed that:

China['s] economic development trajectory remains a leading example of the triumph of humanity over adversity. The exemplary role of the collective leadership of the Communist Party of China in this regard should be a guiding lodestar of our own struggle.

Radical Economic Transformation

Towards the end of Jacob Zuma's presidency, an ANC faction aligned to Zuma pioneered a new policy platform referred to as Radical Economic Transformation (RET). Zuma announced the new focus on RET during his February 2017 State of the Nation address, and later that year, explaining that it had been adopted as ANC policy and therefore as government policy, defined it as entailing "fundamental change in the structures, systems, institutions and patterns of ownership and control of the economy, in favour of all South Africans, especially the poor". Arguments for RET were closely associated with the rhetorical concept of white monopoly capital. At the 54th National Conference in 2017, the ANC endorsed a number of policy principles advocated by RET supporters, including their proposal to pursue land expropriation without compensation as a matter of national policy.

Symbols and media

Flag and logo

The logo of the ANC incorporates a spear and shield – symbolising the historical and ongoing struggle, armed and otherwise, against colonialism and racial oppression – and a wheel, which is borrowed from the 1955 Congress of the People campaign and therefore symbolises a united and non-racial movement for freedom and equality. The logo uses the same colours as the ANC flag, which comprises three horizontal stripes of equal width in black, green and gold. The black symbolises the native people of South Africa; the green represents the land of South Africa; and the gold represents the country's mineral and other natural wealth. The black, green and gold tricolour also appeared on the flag of the KwaZulu bantustan and appears on the flag of the ANC's rival, the IFP; and all three colours appear in the post-apartheid South African national flag. The Grand Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach used an identical but unrelated flag between 1813 and 1897.

Publications

Since 1996, the ANC Department of Political Education has published the quarterly Umrabulo political discussion journal; and ANC Today, a weekly online newsletter, was launched in 2001 to offset the alleged bias of the press. In addition, since 1972, it has been traditional for the ANC president to publish annually a so-called January 8th Statement: a reflective letter sent to members on 8 January, the anniversary of the organisation's founding. In earlier years, the ANC published a range of periodicals, the most important of which was the monthly journal Sechaba (1967–1990), printed in the German Democratic Republic and banned by the apartheid government. The ANC's Radio Freedom also gained a wide audience during apartheid.

Amandla

"Amandla ngawethu", or the Sotho variant "Matla ke arona", is a common rallying call at ANC meetings, roughly meaning "power to the people". It is also common for meetings to sing so-called struggle songs, which were sung during anti-apartheid meetings and in MK camps. In the case of at least two of these songs – Dubula ibhunu and Umshini wami – this has caused controversy in recent years.

Electoral history

National Assembly elections

| Election | Party leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Nelson Mandela | 12,237,655 | 62.65% | 252 / 400

|

ANC–NP–IFP coalition government | ||

| 1999 | Thabo Mbeki | 10,601,330 | 66.35% | 266 / 400

|

ANC–IFP coalition government | ||

| 2004 | 10,880,915 | 69.69% | 279 / 400

|

Supermajority government | |||

| 2009 | Jacob Zuma | 11,650,748 | 65.90% | 264 / 400

|

Majority government | ||

| 2014 | 11,436,921 | 62.15% | 249 / 400

|

Majority government | |||

| 2019 | Cyril Ramaphosa | 10,026,475 | 57.50% | 230 / 400

|

Majority government |

National Council of Provinces elections

| Election | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 60 / 90

|

|

| 1999 | 63 / 90

|

|

| 2004 | 65 / 90

|

|

| 2009 | 62 / 90

|

|

| 2014 | 60 / 90

|

|

| 2019 | 54 / 90

|

Provincial legislatures

| Election | Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | KwaZulu-Natal | Limpopo | Mpumalanga | North-West | Northern Cape | Western Cape | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | |

| 1994 | 84.35 | 48/56 | 76.65 | 24/30 | 57.60 | 50/86 | 32.23 | 26/81 | 91.63 | 38/40 | 80.69 | 25/30 | 83.33 | 26/30 | 49.74 | 15/30 | 33.01 | 14/42 |

| 1999 | 73.80 | 47/63 | 80.79 | 25/30 | 67.87 | 50/73 | 39.38 | 32/80 | 88.29 | 44/49 | 84.83 | 26/30 | 78.97 | 27/33 | 64.32 | 20/30 | 42.07 | 18/42 |

| 2004 | 79.27 | 51/63 | 81.78 | 25/30 | 68.40 | 51/73 | 46.98 | 38/80 | 89.18 | 45/49 | 86.30 | 27/30 | 80.71 | 27/33 | 68.83 | 21/30 | 45.25 | 19/42 |

| 2009 | 68.82 | 44/63 | 71.10 | 22/30 | 64.04 | 47/73 | 62.95 | 51/80 | 84.88 | 43/49 | 85.55 | 27/30 | 72.89 | 25/33 | 60.75 | 19/30 | 31.55 | 14/42 |

| 2014 | 70.09 | 45/63 | 69.85 | 22/30 | 53.59 | 40/73 | 64.52 | 52/80 | 78.60 | 39/49 | 78.23 | 24/30 | 67.39 | 23/33 | 64.40 | 20/30 | 32.89 | 14/42 |

| 2019 | 68.74 | 44/63 | 61.14 | 19/30 | 50.19 | 37/73 | 54.22 | 44/80 | 75.49 | 38/49 | 70.58 | 22/30 | 61.87 | 21/33 | 57.54 | 18/30 | 28.63 | 12/42 |

Municipal elections

| Election | Votes | % | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995–96 | 5,033,855 | 58% |

|

| 2000 | None released | 59.4% | |

| 2006 | 17,466,948 | 66.3% | |

| 2011 | 16,548,826 | 61.9% | |

| 2016 | 21,450,332 | 55.7% | |

| 2021 | 14,531,908 | 47.5% |

Criticism and controversy

Corruption controversies

The most prominent corruption case involving the ANC relates to a series of bribes paid to companies involved in the ongoing R55 billion Arms Deal saga, which resulted in a long term jail sentence to then Deputy President Jacob Zuma's legal adviser Schabir Shaik. Zuma, the former South African President, was charged with fraud, bribery and corruption in the Arms Deal, but the charges were subsequently withdrawn by the National Prosecuting Authority of South Africa due to their delay in prosecution. The ANC has also been criticised for its subsequent abolition of the Scorpions, the multidisciplinary agency that investigated and prosecuted organised crime and corruption, and was heavily involved in the investigation into Zuma and Shaik. Tony Yengeni, in his position as chief whip of the ANC and head of the Parliaments defence committee has recently been named as being involved in bribing the German company ThyssenKrupp over the purchase of four corvettes for the SANDF.

Other recent corruption issues include the sexual misconduct and criminal charges of Beaufort West municipal manager Truman Prince, and the Oilgate scandal, in which millions of Rand in funds from a state-owned company were funnelled into ANC coffers.

The ANC has also been accused of using government and civil society to fight its political battles against opposition parties such as the Democratic Alliance. The result has been a number of complaints and allegations that none of the political parties truly represent the interests of the poor. This has resulted in the "No Land! No House! No Vote!" Campaign which became very prominent during elections. In 2018, the New York Times reported on the killings of ANC corruption whistleblowers.

During an address on 28 October 2021, former president Thabo Mbeki commented on the history of corruption within the ANC. He reflected that Mandela had already warned in 1997 that the ANC was attracting individuals who viewed the party as "a route to power and self-enrichment." He added that the ANC leadership "did not know how to deal with this problem." During a lecture on 10 December, Mbeki reiterated concerns about "careerists" within the party, and stressed the need to "purge itself of such members".

Condemnation over Secrecy Bill

In late 2011 the ANC was heavily criticised over the passage of the Protection of State Information Bill, which opponents claimed would improperly restrict the freedom of the press. Opposition to the bill included otherwise ANC-aligned groups such as COSATU. Notably, Nelson Mandela and other Nobel laureates Nadine Gordimer, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and F. W. de Klerk have expressed disappointment with the bill for not meeting standards of constitutionality and aspirations for freedom of information and expression.

Role in the Marikana killings

The ANC have been criticised for its role in failing to prevent 16 August 2012 massacre of Lonmin miners at Marikana in the North West. Some allege that Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega and Police Minister Nathi Mthethwa may have given the go ahead for the police action against the miners on that day.

Commissioner Phiyega of the ANC came under further criticism as being insensitive and uncaring when she was caught smiling and laughing during the Farlam Commission's video playback of the 'massacre'. Archbishop Desmond Tutu has announced that he no longer can bring himself to exercise a vote for the ANC as it is no longer the party that he and Nelson Mandela fought for, and that the party has now lost its way, and is in danger of becoming a corrupt entity in power.

Financial mismanagement

Since at least 2017, the ANC has encountered significant problems related to financial mismanagement. According to a report filed by the former treasurer-general Zweli Mkhize in December 2017, the ANC was technically insolvent as its liabilities exceeded its assets. These problems continued into the second half of 2021. By September 2021, the ANC had reportedly amassed a debt exceeding R200-million, including over R100-million owed to the South African Revenue Service.

Beginning in May 2021, the ANC failed to pay monthly staff salaries on time. Having gone without pay for three consecutive months, workers planned a strike in late August 2021. In response, the ANC initiated a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for staff salaries. By November 2021, its Cape Town staff was approaching their fourth month without salaries, while medical aid and provident fund contributions had been suspended in various provinces. The party has countered that the Political Party Funding Act, which prohibits anonymous contributions, has dissuaded some donors who previously injected money for salaries.

State capture

In January 2018, then-President Jacob Zuma established the Zondo Commission to investigate allegations of state capture, corruption, and fraud in the public sector. Over the following four years, the Commission heard testimony from over 250 witnesses and collected more than 150,000 pages of evidence. After several extensions, the first part of the final three-part report was published on 4 January 2022.

The report found that the ANC, including Zuma and his political allies, had benefited from the extensive corruption of state enterprises, including the South African Revenue Service. It also found that the ANC "simply did not care that state entities were in decline during state capture or they slept on the job – or they simply didn't know what to do."

Russian invasion of Ukraine

In March 2022, President Cyril Ramaphosa has faced criticism from opposition parties, public commentators, academics, civil society organisations, and former ANC members for not condemning the invasion; while the ANC youth wing has condemned sanctions against Russia, while denouncing NATO's eastward expansion as "fascistic". Officials representing the ANC Youth League acted as international observers for Russia's controversial referendum to annex Ukrainian territory conquered during the war.